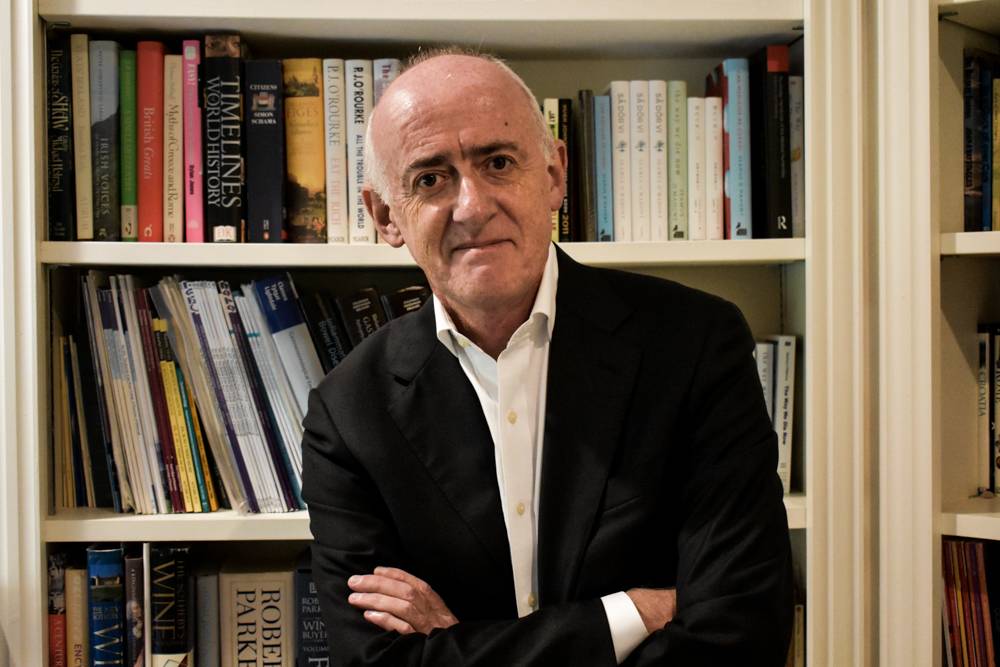

Seamus O’Mahony is a doctor and prize-winning author. He worked for many years in the NHS, returning to his native city of Cork in 2001, where he was a gastroenterologist and clinical professor until February 2020.

His first book The Way We Die Now won the British Medical Association’s council chair’s choice award in 2017. His second book Can Medicine be Cured? was published in 2019, and his latest book The Ministry of Bodies was published by Head of Zeus in March 2021.

He is a regular contributor to the Dublin Review of Books and the Medical Independent. He has written also for the Observer, the Irish Times, the Irish Independent and the Saturday Evening Post. He is a member of the Lancet commission on “The Value of Death” and is visiting professor at the Centre for the Humanities and Health at King’s College London.

Read his work…

Lancet Commission on Value of Death

Book 2: Can Medicine Be Cured?

Book 3: The Ministry of Bodies

Transcript

This transcript is AI generated, so please allow for errors.

Gary: Hello and welcome to the Triage Method podcast. I am Gary Mcgon as always, and I’ve got a special guest this week. So Patty’s not joining us this week. Instead, we’ve got Professor Seamus Mahany, or just Seamus for today. Joining us today. He’s an author, gastroenterologist recently retired, I believe.

But I’ll give Seamus the chance to introduce himself in a moment. We wanted to get Seamus sound because over the last few episodes, if you’ve been listening along, What we’ve been doing is we’ve been discussing basically what you are likely to die from as a modern person, how that’s changed in recent years what you’re likely to die of if you’re 20 versus if you’re 80, et cetera.

And we also talked about some of the things that might reduce your chance of dying either now or in the future. Inclusive of things as simple as all of the things we normally talk about, like exercise, improving your diet, maybe sleeping more, et [00:01:00] cetera. But also some of the more complex things like your socioeconomic status, where you were born, how much money you earn, all those types of things.

And. Seamus has written a couple of books one in particular, which really caught my interest a year or two ago, and that was a book, can Medicine be Cured? And initially, someone sent me this book and they said to read it, and I thought to myself, oh God, it’s just another person who’s, writing, I don’t know, conspiracy theories about how medicine is bad.

And then I realized that, oh, this is actually a professor of medicine himself and who also went to and lectured in u c where I go. So I thought that’ll be worth a read. And I gained a lot from it. So I thought it’d be worth speaking to him today. So Seamus, can you give us a brief introduction to who you are, how you got to where you are today?

Seamus: Thanks Gary. Yeah, I’m I’m from Cork. I went to medical school in Cork. And I [00:02:00] trained and worked in the British National Health Service for many years before coming back to Cork over 20 years ago. And I worked as a consultant physician specializing in gastroenterology at C U H for many years.

I retired. I don’t regard myself as retired, but I re I left that post, or I retired from that post just before the pandemic arrived. Whether that was good or bad timing, I’m not sure what, so right now I’m pretty much a full-time writer. I’m the author of three books, including the one you’ve mentioned.

Can Medicine Be Cured? My first book the Way We Dine Out was published back in 2016. And my most recent book is the Ministry of Bodies, which came out. Last year, I’m currently working on my fourth book which is about the history of psychoanalysis. And I also work part-time in a vaccination center in west [00:03:00] Cork.

I do some work for the medical council. I do some journalism and I’m involved with a fairly big piece of work with the Lancet particular commission on death and dying called the Value of Death. So that’s who I am.

Gary: Very nice. And I just realized there that I think your book there behind me is sitting beneath Ernest Becker’s book, just by coincidence, the Denial of Death.

So you’ve probably read it given that you’re so interested in death and dying. Yes. Yeah. So what is it about death and dying that captivated you? Is it solely something that’s because of your experience in medicine or is it something that maybe is beyond it?

Seamus: I have to be honest in and say that if it were not for the fact that I worked for so many years at the medical cold face to use that old tar cliche, I probably wouldn’t have given it as much thought as I did.

[00:04:00] I wrote about it because death has and dying. Have become essentially medicalized experiences in high income countries like Ireland. So if people are asked, where would you like to die? They would usually say I’d like to die at home, or if not, then in a hospice. But the reality in countries like Ireland and the UK most European countries is that you are far more likely to die in an acute general hospital.

Okay? So in Ireland, more than 50% of all deaths take place in acute general hospitals which was my working environment. And over many years, it struck me that people were not having what might be called a good death in this particular type of environment. It struck me that medicine and healthcare can’t provide the the [00:05:00] support, the ritual, the meaning that people need at the end of life that people and their families need at the end of life.

And I wrote about death and dying from that experience of somebody working in the acute healthcare sector where most deaths take place. So that’s what prompted me to write about it. First day was my own

Gary: experience. And between then and now, given that you’ve written a book about it and you’ve also been working on the Lancet Commission, is there much that you’ve changed your perspective on that you wouldn’t have had, had you not gotten so deep into the topic?

Seamus: Completely? Yeah. When I wrote this book, which is now six years ago or when it was published, it was six years ago, there was a sort of slight unspoken vibe around the book, which was why is a gastroenterologist writing about death and dying? Because up, up to then the sort of books were written by, people from the palliative care [00:06:00] community, by and large, or maybe geriatricians.

Why was a gastroenterologist writing about death and dying? And the truth is that the the heavy lifting of death and dying was being done in the acute hospitals, not in the hospices. And every day of my working life, I was seeing. Young people dying from alcoholic liver disease in large numbers.

That was within my specialty work in gastroenterology, but I also had another hat, which was general medicine. And general medicine in acute hospitals is mainly the care of very frail, elderly people with multiple comorbidities who have a high, a relatively high mortality. I once did an audit and found that about one in 10 people admitted acutely under general medical care died during that admission.

So did it change my perspective completely? [00:07:00] I came around to the view that care of the dying was not just something. For palliative care doctors and hospices, it was the duty of every doctor. It is one of the core duties of every doctor up to then, like many doctors, I had viewed the death of a patient as somehow a failure on my part of failure, of the part of medicine.

And yet I’ve come around to the view that it’s not that at all we’re all going to die. You can’t regard death as a failure, and all doctors need to regard the care of the dying and the relief of suffering as actually their core function. But I also came around to the view that medicine alone and healthcare alone cannot provide the, the support that people need and that death and dying must go back again [00:08:00] to communities and to families.

And that it needs to be taken out of healthcare. I’m not arguing that it needs to be completely unmedicalize, but it needs to be demedicalized and families and communities need to be given the support that they need to once again feel confident about caring for and looking after dying people.

So I very much changed my whole personal view on it. Having worked with the last commission over the last several years I’ve been working with people from not just all over the world, different countries but also people from different backgrounds, not just healthcare backgrounds, but backgrounds like, like economics, religious life, philosophy, sociology.

So I’ve developed a far more, I hate to use the word holistic, but that’s what I’ve developed a holistic view of of death and [00:09:00] dying. And our commission report is called The Value of Death. And we’re arguing that death should be seen as having value. It’s not just something that we should run away from and try to avoid at all costs.

It has value and that looking after the dying also is not a burden, but it should be a gift. So I’ve come around to a very different approach. I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve, got to work with and meet people from. Such different backgrounds to my own. So I feel very blessed in that regard.

So writing that book has given me, has opened all sorts of doors to me. And I’m very grateful for it.

Gary: Very good. And I recall reading a told Grande’s book a few years ago, but I think it, is It Mortal or Being Mortal is the title one of those Mortal? Yes. Mortal. Yeah. And yeah, I remember him, him discussing quite a bit about [00:10:00] the some of the differences between cultures, because I think he’s Indian himself by ethnicity.

Yes. And that he talks about the nature of multi-generational families and dying at home and that type of thing. Yeah. So I’m wondering from your perspective, do you think like from the commission and working with people with different backgrounds, are there better examples of how to do it, so to speak, of how to die?

Seamus: Yes, there are. So one of the members of our commission is a doctor from Kerala in India, and he was involved and still is in setting up a community palliative care program in Kerala, which has become a model for such programs now throughout the world. And what they did was, this is going back 20 or more years ago, is they set up these networks, community networks, doctors and nurses were certainly involved, but they didn’t lead [00:11:00] them.

These networks were. Led mainly by volunteers laypeople, LEK, that they were not from they were not healthcare professionals and they built up these networks to look after people who were dying. And not only people who were dying, but people with chronic severe illness who were at home.

And this community program has been very successful in terms of providing a holistic quality of life-driven care of people at the end of life. So that is the model for low-income countries that could certainly. Be applied around the world. There are models in high-income countries, for instance, the Compassionate [00:12:00] Communities program.

And there are several examples of this, most notably in Hackney in East London, where again it’s a community-based program delivered mainly by lay volunteers. The local hospice is used as a sort of centre because they need some sort of physical geographical centre. But these programs are not driven or led by healthcare professionals.

They’re driven and led by local people and local volunteers. And they work with charities, they work with religious groups, and they try to bring in everybody in these communities. I’m not saying that they’re perfect or without their problems, but they are I think models of how we might develop.

Care of the dying in the future.

Gary: I think there’s an interesting link there as well between, I think your two books, because one of the things I believe you talked about early on in the book [00:13:00] was oh in Can Medicine Be Cured is about, for example, the field of oncology I think is a good example where there’s constantly new drugs, new monoclonal antibodies, that type of thing that maybe extend progression, pre free survival by 20 days or something along those lines.

Yes. And with that kind of culture of, trying to clutch at every last straw through, through drugs or whatever it happens to be, you’re incentivizing, I think, on the end of the patient and the doctor to do everything right until the end and not allow death to even be a possibility. How, yes.

How do you rec, how have you reconciled that yourself? As a medical professional, because it might, it must be incredibly difficult, I think, particularly with younger people. Yeah. To let it happen, so to speak. Yes.

Seamus: Yeah. What you’ve just encapsulated there was one of the factors that drove me to write the first book.

I found myself living and working in a medical culture, which was pretty much [00:14:00] as you describe, and there was this incredible reluctance as I saw it, to be honest with people at the end of life. And we were constantly, when I say we, doctors. We were constantly incentivized to, yeah, let’s do another scan.

Let’s order another round of chemo. We might try this, we might try that. We were avoiding. Always, and not always, but generally we were avoiding what I called the difficult conversation. It was much easier in the course of a busy clinic or a stressed outward wrong to say, ah, yeah, we’ll do another scan or we’ll get the oncologist back or we’ll do this or we’ll do that.

Now you’ve mentioned oncology and I have been very hard in oncology because I believe that within that particular medical community, there is this culture of pushing things to the bitter end. [00:15:00] Now, there are many people within oncology who are not like that, but I think that they’re still a minority.

And you mentioned the use of, these meaningless. Surrogate markers that are used in oncology trials such as progression-free survival and so on. And I wrote about that in the second book. And these meaningless surrogate markers are driven by drug companies, hand in hand with the academic oncology community to force through the registration of new drugs which very often have minimal or no benefit and come with side effects and huge costs.

So I wrote about, for example, a particular drugs fund in the NHS called the Cancer Drugs Fund, which when [00:16:00] David Cameron was Prime Minister about 10 years ago, pushed through this and he was responding to pressure from. Lobby groups, patient support groups, drug companies to fund drugs, which had been turned down by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

Nice. Which is this government body which oversees new drugs, new technologies, and makes a decision on whether this state should fund them. And he was under such pressure from lobby groups, as I say, patient support groups drug companies, oncologists, and so on, that he funded a whole bunch of drugs that had been turned down by NICE to the tune of 1.3 billion and a paper was published by a group of oncologists looking at.

[00:17:00] These drugs and found out that of the, there, I think there were 47 drugs, they found that two-thirds of them had absolutely no benefit and came with side effects and huge cost. One third of them extended life by an average of three months. Now, I used that example because the money that was wasted on this particular cancer drugs fund would’ve paid for every hospice in Britain for a year and a half.

And at the time, and hospices were closing down because they didn’t have enough money just to keep going. Hospices in Britain rely on charity for two-thirds of their running costs. So it seemed to me that we had our priorities very badly wrong in medicine and certainly. Oncology [00:18:00] would have far greater prestige and power within academic medicine than, let’s say, for example, palliative care.

So just another example of that being in the UK there are 10 times more academic trainees in oncology than there are in palliative care. So that gives you an idea of the imbalance that we have in modern medicine. No, I’m not anti-oncology. If I got cancer, I’d want to have the best treatment that’s available, of course I would, but would I want to have futile treatments just because, the oncologist doesn’t want to have a difficult conversation with me and my family.

No, of course not. So I think there is a happy balance to be reached somewhere.

Gary: And I think the fascinating thing from my perspective is about. How there’s a self-perpetuating cycle created because like we’ve discussed there, there’s the doctor and there’s the pharmaceutical company, for example, [00:19:00] creating irrelevant surrogate markers.

But then also there’s the br bringing that into the public domain through media and the end user who obviously assumes that things like extending life or this new drug or the war on cancer, that these are all purely virtuous goals. And one of the things that you mentioned in the book is about this concept of raising awareness that this is something that’s seen as always an inherently positive thing, that we should be ra raising awareness about this disease, that disease whatever it happens to be, and that there’s actually potentially a downside there. Can you speak to that a little bit?

Seamus: Yeah. I call this raising awareness game.

In medicine, my disease is better than your disease. And I had noticed over a sort of period of [00:20:00] several years that doctors were being dragged into these campaigns which were driven on social media and so on, and so certain diseases and conditions were. Becoming to be regarded as more worthy of investment than other diseases.

So for example, we had very slick campaigns from obviously cancer, the cancer community, but also other communities like cystic fibrosis, for example. And it seemed to me that it was socially unjust to fund healthcare and particular diseases on the basis of [00:21:00] awareness and publicity campaigns. And it seemed to me spectacularly unjust that some.

Diseases were more worthy of investment than others, that some people were deemed to be more deserving than others. And it seemed to me that those who shouted the loudest, those with the sharpest elbows, those with the best awareness campaigns and the best publicity people working with them were getting the funding and the resources that other diseases were not.

So I remember Joe Harbison, who’s a stroke physician in St. James’s in Dublin, wrote a brilliant piece in the Irish Times about five years ago when he was National Director of the stroke program saying, stroke patients are just [00:22:00] as worthy of investment as cancer patients. And he was right. And. We, had the example of orcambi this drug for cystic fibrosis, which has an, I think we’re all agreed, a very modest benefit.

And yet the state funded this drug partly because the cystic fibrosis campaign was so effective from a public relations point of view. Let’s go back to the other end of the medical swamp where I worked alcoholic liver disease. Now people with alcoholic liver disease are not regarded as worthy of support in the same way as people with cystic fibrosis, people with cystic fibrosis, you inherit this disease.

There are young people. People with alcoholic liver disease it’s regarded as a self-inflicted condition. We didn’t have a national program for alcoholic liver disease despite the fact that this was an epidemic [00:23:00] over the last 20 years despite the fact that it was targeting people.

Very young people in there, as young as in their twenties were dying of alcoholic liver disease. So I think that these awareness campaigns are a form of social injustice. I don’t think doctors should get involved with this game of my disease is better than newer disease. And I am incredibly wary of every time I see some something in the papers or on television pushed by a particular patient support group.

Gary: Yeah. And it’s interesting cuz o obviously, like we, we get exposed to those in medical school as well, where we’ll have certain, groups coming in to tell us about their disease and their experience and all that type of thing. And it’ll be with a particular patient advocacy group, although we haven’t had too many of them since the pandemic, but it was just in first and second year.[00:24:00]

Yeah. But yeah, there, that exposure is there. And what was I gonna say there? Oh yes. On the note of raising awareness, You spoke about there about that there with respect to particular diseases and my disease is better than yours. But I think that there, there’s probably also an extension of that potentially goes even further where raising awareness to raising awareness about disease, about symptoms, about conditions can potentially increase the amount of false positives of people reporting those symptoms.

An example of that I would’ve seen a lot would’ve been, I did physiotherapy previously, and it was one of the reasons I wanted to do medicine and what I observed was that among people who would have back pain or something like that, there was always this. Idea if they had done their own research or been exposed to information about back pain, that it was something serious, that they’ve got maybe nerve compression or they, oh my God, I could have [00:25:00] spinal cancer, or this type of thing, when in fact the va, vast majority of people will get back pain and it’ll get better.

And it doesn’t need to be medicalized in the slightest, for the vast majority of people. And. If you are raising awareness about these types of things, something closer to hu to home for you probably would be something like i b s maybe you’re potentially taking more people from the community into the medical net by medicalizing what are very much just everyday symptoms.

Is that something that, that you’d agree with, that you would’ve seen much of?

Seamus: Yes. And you mentioned irritable bowel syndromes. Fact, irritable bowel syndrome is probably part of being alive. Who hasn’t had, stomach cramps or ball upset if they’re stressed. It’s actually, it’s a variant of normal physiology and yet we’ve medicalized all of this.

An awful lot of awareness is driven by commercial interests. You’ll find if you scratch the [00:26:00] surface of any patient advocacy group, you’ll find a drug company somewhere. And if you look at any advert for any awareness, medical awareness campaign, you’ll find in the small print somewhere that a drug company has supported it.

So I thought, could it be anything to do with prostate disease? You, I’ve noticed that it’s there’s a drug company usually involved there somewhere. So awareness is being driven I think mainly by commercial interests who want to create a bigger pool of patients for their product.

Back pain, as you say is incredibly common and the opioid epidemic in America was partially driven by medicalizing mild to moderate distress and [00:27:00] mild to moderate pain. There was a campaign, a very focused and vigorous campaign to persuade doctors to provide op, to prescribe opiates for conditions that should have been dealt with by physiotherapy, exercise, non-invasive, non-pharmacological interventions.

So there is a huge commercial advantage there to medicalize. Very common. Relatively minor. You, human problems. I suffer from backache myself, but I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t dream of taking long-term medication for it because the answer as I need hardly tell you lies elsewhere.

I do worry about these campaigns. I do worry about this bringing into the medical sphere variations in normal human experience. And it goes across everything, mild dysthymia [00:28:00] has been processed into clinical depression over the last couple of decades. It’s very easy now to get a tickbox diagnosis of depression.

And thus a prescription for an SSRI, you just need to have persistent low mood for as little as a few weeks. And according to this criterion, you are suffering from clinical depression. So we have transformed, as I say, mild to moderate human distress into disease labels. And this has been driven, I think predominantly by commercial interest.

Gary: I was, you brought up the psychiatric examples. I was recently on my psychiatry placement and. I, the, that same tone was what was coming from the psychiatric doctors, that they would have patients coming into the, to their community clinics. And, the patient might leave and they’re turning around to us, the [00:29:00] students, and they’ll say, that’s personality.

That’s life. That basically it’s, they were, they might have relationship or issues with their relationships, basic social issues, maybe socioeconomic problems, these types of things that were maybe causing distress or anxiety at the time. But it’s very much circumstantial related to their life.

And yeah, they’re attending psychiatric services for, medications and medication changes and type and things like that. And the psychiatrists are saying they shouldn’t be here, we shouldn’t be seeing them. That’s not a reason for referral. And it just goes back to that example of, I.

Extending the medical net into the Yeah. Normal variations in the human experience.

Seamus: Absolutely. And then on the other side of psychiatry, people with serious long-term mental illness, psychotic disorder and so on, struggle to get decent care. Yes. They have a significantly [00:30:00] shortened lifespan.

They struggle to get good community and hospital care while psychiatrists are being inundated with the sort of work that you’ve just mentioned. So there are several downsides to this extending of the medical net over human experience.

Gary: Yeah. And it’s actually quite sad. My, my sister, she works as an assistant psychologist herself and she’s shared these concerns with me about how about the types of adolescents and kids even that are attending counseling services sometimes.

Because if you think about the example of, let’s say, like you said, psychotic illness, schizophrenia, people who need, more intensive intervention both medical and otherwise and support with their life. And you compare that with. People who are accessing services in adolescents for, let’s say they’re con, they’re confused about their gender or their identity or[00:31:00] they’re anxious about school.

And this was something that the one of the psychiatric doctors said as well, is that you’d be fascinated by the amount of teenagers who really want a diagnosis these days. Even compared to 10 years ago when I was in school. It wouldn’t have been cool to, be telling people about your mental health or mental illness.

Whereas now the psychiatric doctors are saying that, no, this is actually something that they want. And my sister says it as well, that among adolescents, it’s actually almost cool to have something to discuss about your mental health or mental illness.

Seamus: Yes. And I think that this is the downside of de-stigmatizing Yes.

Mental illness, that we now have a situation where diagnosis becomes identity. Yeah. So when you are a teenager, and particularly if you’re going through a difficult patch as a teenager, identity means everything. Yes. So just to take a random example, I watched a program that David Bade, the comedian and writer [00:32:00] did recently on BBC about social media.

And he interviewed his own daughter, which I thought was quite brave, who suffered from an eating disorder. And she told him that this was very much exacerbated by social media. And what she said, which was fascinating, was that having an eating disorder gave her an identity. And that this was driven by social media, okay?

It was not an identity you might choose, but nevertheless, when you’re a confused teenager going through difficult times, an identity is incredibly important. So we have this patient driven demand, which you have mentioned for diagnosis. So I dunno how often I’ve read recently pieces in newspapers, usually from young people saying I was diagnosed with.

A D H D or autism or Asperger’s, and [00:33:00] suddenly everything made sense and that’s fine in some ways, but in other ways you have people who have, relatively minor variations from the average human experience. And this has being given a label. And I don’t think this helps people, for example, with severe autism.

It’s, I don’t think it’s helping their case very much when you expand the diagnostic pool to include people with relatively minor variations in human experience and behavior and giving it a medical diagnosis. But as you say, this is driven very much by patient demand. Doctors are very often accused of wanting to medicalize everything, and I’ve argued that’s not really the case.

The demand for medicalization has come predominantly. From the patient population looking for a diagnosis. In my own work, for example, people with [00:34:00] irritable bowel syndrome didn’t particularly want an explanation of along the lines. It’s, it’s very common.

It’ll come and go. It won’t kill you. Here are a few things that won’t help, that will help. There was a there was demand for diagnosis of food allergies, food intolerances and so on. So what I’m saying is that very often a medical diagnosis is becoming an identity, particularly for young people, and I’m slightly concerned about this as a social phenomenon.

Gary: Yeah, me too. And I think it, it’s quite sad as well because it’s, I guess it’s those who have the more sinister diagnosis that would do anything to not have them. And then it’s such a absolutely paradox almost. It’s those who are Yeah. Who are not ill, who want something yeah. To be there. Yeah. I don’t know, I don’t know how you solve that, to be honest.

I think it’s there’s ultimately no way because it’s a, it’s almost a self-perpetuating cycle because if you’ve got drug companies and doctors representing those drug companies [00:35:00] and they’re, they run awareness campaigns about X, Y, and Z, and then you’ve got patient populations who are receiving that through the media then, and they go to their doctor, the doctor’s almost left in the middle saying who do I listen to?

Very difficult. Yeah.

Seamus: Yeah. And gps are at particularly the sharp end of all this kind of of this kind of thing. And When you have international social media, you have a vast dissemination of information. Some of it good, some of it bad that people just didn’t have access to 25 years ago.

So that’s, that’s driving it. That’s driving it also. And like you I don’t have a simple, I don’t have a simple answer to it. And doctors very often now see themselves as in a consumerist sort of. Model as service providers. The sort of, I, I don’t know how you feel in medical school, but I get the impression that there is a subliminal [00:36:00] message to medical students and trainee doctors along the lines of the customer’s always right.

Yeah. And that you don’t want to be telling people things they don’t want to hear. And yet I would argue that is actually part of the role of a doctor is to tell people stuff they don’t want to hear. But that’s a rather unfashionable view n nowadays.

Gary: Yeah, I think so. I think that, there’s moving away from the. Paternalism, of medicine in the past is something that you can certainly extract positives from. However, one of the downsides of that is that if you effectively equalize everyone on the same level, the doctor and the remainders are remaining members of the md t as well as the patient, then ultimately you’re allowing the.

The culture of the day to almost determine the medical decision making in some sense. Because if the patient comes in, particularly, I think for gps, this happens a lot. And they’re saying the GP has seven minutes [00:37:00] and the patient comes in and says, I want this test, and this test because I want to optimize this and I want to improve that.

And, I read about this new LP little, a cholesterol test that I want to get and this type of thing. You’re left thinking, what do I do now? I’m supposed to listen to the patient, but my b my knowledge says they don’t need these tests, but then they’re an unhappy customer. What do you do?

Seamus: Yeah. Yeah. I, yeah, I think this is probably one of the greatest problems contemporary medicine in high income countries faces is this type of consumerism that that you mentioned. And I sometimes wonder if we shouldn’t draft up a societal contract. Between doctors and patients to say, this is what we do.

This is what we are here for, this is what we don’t do. That sort of contract used to be unspoken and implicit. But I just wonder whether it should be formalized so that people are aware this is what medicine can [00:38:00] do what it can afford to do. This is what it doesn’t do. And again, I’m slightly worried about the sharp elbow elbowing other people aside.

And I think that there is a social justice issue here. It gets back again to my diseases better than your disease. I think the sharp elbow are constantly getting to the top of the queue in everything to do with medicine. And I think that there is a bit of a funk within the profession. We don’t want to address this issue.

We don’t want to take on. Or question this consumerist model everything now is geared towards making sure that the person after their seven minutes goes out the door feeling vaguely happy. And you can’t always do that. I suppose you can do, if you want to be completely consumers and say, yeah, I’ll order an M r I scan and I’ll do this incredibly expensive blood test and I’ll prescribe an opiate for you.

That makes people happy for the five minutes that they’re walking out the [00:39:00] door. But is it the right thing to do? And I think doctors need to realize that sometimes you might have to make people transiently dissatisfied and unhappy to do the right thing. And that’s a difficult message to get across.

At the moment to our patients, and indeed within medicine the training now, as I say, is all about empathy. Rolling back the old paternalistic model, and that’s all very good. But at the same time, I think that there has to be an engagement with the, these realities that we’ve mentioned and these tough questions.

And I don’t think medicine as a culture wants to have difficult conversations or engage with difficult questions at the moment, which worries me.

Gary: Yes. And you spoke of the fact that it might necessarily be in the patient’s interest to, to get, let’s say a scan or some sort of medication at that time, but in some cases it can actually be [00:40:00] extremely harmful.

And I know you’re aware of this, but this is something that. Was one of my kind of reasons for going into medicine. Again, going back to the. The back pain that I mentioned previously. One of the things that has been a big talking point in the last 10 to 15 years in the physio space and in especially just related to the back pain generally, so involving neurosurgery, neurology, et cetera, is the fact that there’s almost an epidemic of overdiagnosis and overtreatment for problems that aren’t really problems, or certainly aren’t sinister problems.

The classic example of that would be patient shows up to. The gp. GP doesn’t have much time. They’ve got backache. I’m not sure where it’s coming from. You’ve got back pain we’ll send you for an m r i. You go for the m r i, you find an incidental finding of, I don’t know, a facet joint arthropathy and okay what will we do with that?

We’ll refer you to, I don’t know, radiology or neurosurgery, and then you get an [00:41:00] injection from anesthesiology to see if you can get rid of that pain. And then, okay, we give you opiates and then you’re developing hypersensitivity and suddenly you’ve seen 15 medical professionals. You could have spent, especially in, in, in the US you could have spent tens of thousands of dollars and potentially found yourself with an opiate addiction and worse pain down the line.

So it’s it’s not like that. It’s just a, when the doctor’s making this, the decision to not give you a scan, it’s not just a case of you don’t need this and we have to give re resources. Elsewhere, but rather that there’s potentially grave harm for you down the

Seamus: line. I completely agree, and this is why it’s much easier to do that in the seven minutes that you have in your outpatients than to sit down and go through the reasons why you’re not going to send the patient for an M R I scan.

Why you’re not going to prescribe O opiates, why you’re not going to refer to a neurosurgeon. This [00:42:00] takes time and this neatly gets me back to death and dying again. It’s much easier not to have these conversations and the culture within medicine now disincentivizes these conversations. It’s a way easier to, do a test or an intervention than to have a difficult conversation and to tell people things that they potentially might not want to hear.

And there’s, there was a very I talk a lot in the first book about the difficult conversation and I quoted more recently an Australian palliative care doctor who said two weeks in intensive care can save you a whole lot of difficult conversation. It’s actually much easier to roll the patient down the line into the next phase of the medical sausage MA machine than to sit down and have these conversations, [00:43:00] and this gets back to death and dying again.

People are having these difficult conversations about intervention and about escalation of care at the worst possible time they’re having these conversations. Their families are having these conversations at a time of crisis when the patient might be down in the ED on a trolley on a bank holiday weekend.

And I would argue that these are conversations that you can have at a much better time and in a much more appropriate environment. So for example, people with chronic liver disease, people with end stage C O P D, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema people with any form of advanced cancer.

Once you have made a diagnosis as a doctor of a limiting condition, I would argue that there is an onus upon you to engage [00:44:00] with the patient, with their family on what the future is going to hold for them to. To try to get a, an idea from them what’s important for them, what sort of treatments and intervention they would or wouldn’t like to have done.

So as a very good model run by a friend of mine who’s a specialist in lung disease works in Scotland, guy called Robin Taylor. And he has a particular interest in the management of people with end stage C O P D emphysema. And he has a very simple criterion for having this difficult conversation. You ask yourself as a doctor, would you be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?

And if the answer to that question is no, I would not be surprised, then the onus is on you. To engage with that patient and their families to [00:45:00] sit down with them, not just once, but on several occasions, and to give them time, take it away from the busy outpatient with 50 people in the waiting room, give them time, sit them down and say, look, this is what’s happening.

You have this disease. The likelihood is that you are going to have an acute crisis at some stage in the next year, which will land you in hospital. We have options in terms of should you have non-invasive ventilation? Should you go to intensive care or should you just have palliative treatment?

Is there an option for you not to go into hospital? What matters to you and your family? And so on. But these conversations are not happening in acute hospitals. And these conversations, if they do happen, are happening at a time, the worst possible time. When people are stressed, it’s a time of crisis. They can’t take in what you’re saying.

They find it very difficult to make a decision. [00:46:00] And I wrote the first book, the Way We Die Now, partly to express my, my frustration that and a degree of outrage that this was happening, that people were dying without these conversations happening. They were dying without knowing what was ahead of them.

Their families were confused and disorientated. We had this culture in hospitals of not having this conversation of not engaging with people. Very often, doctors were responding to pressure from families. Don’t tell Dad to kill him. Oh, do not. Don’t for god’s sake, don’t tell my father he has cancer or whatever.

So there was, doctors are constantly disincentivized from having these conversations. And if there was one message I would want to get through from, both from my book and from my work with the Lancer Commission is that this is not a difficult conversation. It should be regarded as an essential conversation.

And it is part, it is a core part of your duty as a [00:47:00] doctor looking after people with life-limiting disease. But the culture within the profession of medicine, the culture within acute hospitals puts up barriers to you as a doctor having these conversations,

Gary: I suppose as well. There’s the, almost like the kind of hero story of you as the doctor that makes you feel like, all right, I’ve given this patient a potentially terminal diagnosis, but shouldn’t I give them hope and shouldn’t I do everything I can to.

Have them walk outta here and it’ll be on the news and in the newspaper that this person was miraculously saved.

Seamus: Yeah. I think we confuse hope with optimism. Yeah. And hope can mean many different things. For example, for a person with a life-limiting disease, you can instill hope by making sure that person has proper symptom controlled, that their wishes are taken on board, [00:48:00] that there is a plan in place that you are regarding as important their wishes and their priorities.

That’s can instill hope in people. It doesn’t mean that you’re going to extend their life or that you’re somehow going to miraculously reverse this life-limiting disease. That’s false optimism, which is different to hope. So hope comes in many different gues and I think the medical profession constantly confuses hope with optimism.

And there are two entirely different things. So I think to this day, these conversations are not happening with patients and their families. I noticed within liver disease, which was part of a large part of my work, that there was a culture within that specialty of not having these conversations because [00:49:00] the specialty was very much focused on technological intervention and a biomedical sort of paradigm, which is fine.

But one of the previous LANCET commissions was on. Addressing this epidemic of liver disease that I’ve mentioned. So there’s been an epidemic of liver disease in Britain and Ireland over the last 20 years, driven by alcohol consumption. And the Lance had produced a document now about 10 years ago, and they managed to produce a 25,000 word document without one mention of palliative care at all in this entire document.

Now, the liver disease community, the hepatology community, is slowly coming around to this. And the one body, the British Association for the Study of the Liver, for example, has labeled end of life care and palliative care for people with chronic liver disease as the greatest unmet [00:50:00] need. And this is true.

So you know, there is a culture within medicine which discourages doctors subliminally. This is not something that is. Spoken about, but there is a subliminal discouragement against having these conversations. And I guess my books were arguments as to why we should have these conversations, and that is part of our core duty.

Gary: And with a us just pointing out all of the problems and having no solutions, you mentioned your contract previously that you, did you drop a contract between doctors and society broadly? Yeah. And I suppose that gets back to one of the things I wanted to touch on in, in this podcast, and that is, the role of the modern doctor.

So you’ve been hired by Mial Martin. He said Seamus, I want you to draw up this contract between all Irish doctors and society. What are you [00:51:00] gonna include in it?

Seamus: Okay. I would. Include. Okay. Yeah let’s start at the top. That doctors should regard the care of the patient as their first and only priority.

But that they must do this within the context of living and working In a society where resources are limited and finite, doctors should provide only those treatments that have an evidence base for effectiveness. Doctors should not be driven by commercial gain and that their sole priority should be the care of the patient.

Doctors should regard as a core part of their [00:52:00] duty honesty. Doctors should regard all doctors should regard the relief of suffering as their primary duty, not the saving of life. The relief of suffering is the core duty of a doctor. Patients should have to accept that. They will sometimes have to hear things that they don’t want to hear, that they will sometimes be denied, tests, treatments, and interventions that they’re demanding.

There is this push now to have the new paradigm of medicine as a partnership and a partnership. Friendships, marriages are all about give and take, and that will have to be the same with the doctor, patient relationship. So I think that there is, Room for a new model of medicine, which moves away from both the paternalistic model on the one hand and the consumerist model on the other hand, to a more [00:53:00] thoughtful form of partnership which recognizes broader societal concerns and the fact that resources are finite.

So I think that those are the bullet points that I would put in a new contract between medicine and society. I love

Gary: it. I’m sure it’s not the first time you’ve thought about those bullet points. If it was very impressive, just rattle them off. And tell me then, as you look forward to the future, beyond your career.

I think you, did you graduate in 1983? Is that right?

Seamus: 1983? Yeah.

Gary: So just work, do the battles this, eh? Yeah. So you’ll be UCC class of 83 and I’ll be UCC class of 20, 23. So 40 years. 40 years. Okay. Alright. So 40 years. And in the 40 years prior to your own graduation, I think you had experienced a lot of, what you referred to as the golden age of medicine.

Antibiotics were doing a great job. You had, streptomycin for TB and all these different treatments that [00:54:00] led to a lot of progress over the last 40 years. Things maybe have slowed down a little bit. Yes. And in the next 40 years, do you think that there will be significant advancements?

Do you think that all of these steps in molecular biology and all that sort of thing will get us anywhere? Or will it be something different?

Seamus: Yeah. Okay. I think it’s not so much will this, do we want it? So we, when I say we, I mean we, the human race will have to make. Some very tough decisions as we face into a coming century of climate crisis overpopulation and diminishment of natural resources.

What we want from medicine. Do we want medicine to go along the route as it seems to be [00:55:00] going at the moment where, for example, there is a feeling within bio gerontology that life extension interventions will probably emerge over the coming decades. Do we want that? Do we want, do we really want people to live to be 150 or 200 in a world that is already overpopulated?

In a world whose resources are shrinking? In a world where we have a climate crisis, in a world where people in poor countries, in the global south, most people dying, facing end of life in the global south cannot access morphine, let alone formal palliative care. So we have to ask ourselves, do we want to deal with that?

Or do we want people in rich countries to live to be 150 or 200? [00:56:00] So those, I think the questions that we’ve, we have to ask are more moral than scientific. I think to be honest, that there is a high likelihood that if we continue down this biomolecular road, that we will find interventions that will prolong life at huge cost for a tiny minority of very wealthy people who live in very wealthy countries.

But we have to ask ourselves, who benefits kui Bono? Who benefits, or do we want a world where there might be some degree of equality where the relief of suffering might be regarded as more important than the extension of life of very rich people? So maybe these are the questions that we want to ask about medicine.

Now, getting back to the golden Age, I argue in the second book that there was a period of 50 years from about the mid thirties, the mid eighties, which I just missed, which was the [00:57:00] golden age. I took the example of my own uncle. Who died of spinal tuberculosis as a teenager in the 1940s and two years after he died.

The first ever randomized controlled trial is published by the British Medical Journal, which shows that streptomycin is highly effective against tuberculosis. And he just missed out. So you had this dramatic acceleration of medical innovation. So medicine before then was largely ineffective. And we had this golden age where you had suddenly everything arrives.

You have antibiotics, you have a cure for tuberculosis, you have vaccines. We forget Cork City was closed down in the 1950s. We were, quarantined at the whole city because of Poliomyelitis. There are still people in their sixties now who bear the scars and the. [00:58:00] Infirmities of polio from then.

So we had vaccination, CT scanning organ transplantation and so on and so on. And you might argue that these were the low hanging fruit that were all hit took an awful long time for humanity to reach the low hanging fruit. But anyway, in those 50 years we had this dramatic innovation in medicine.

This had the downside then of creating what I would call the medical industrial complex and the medicalization of society and the expectation that medicine would solve all of our problems, not just medical problems, but existential problems. Which brings us back to our, our slightly worried teenagers turning up, demanding a diagnosis at psychiatric clinics.

So we had this vast extension of medicine over all of our lives so that this was the downside of the golden age. We now have a different age where yes, there is progress in terms of, the [00:59:00] molecular biology and so on, but that progress while it’s there, and I don’t deny it for a moment, is of a much slower pace than the 50 years of the golden age.

So when Joe Biden was Barack Obama’s vice president, he launched this cancer moonshot back in 2015, it with all these targets didn’t reach any up there. No. Targets, I hear Sadi Javi, the health secretary in the NHS, has declared War on cancer. I think other thing he’s read is history books. Richard Nixon declared War on Cancer in 1970 years late.

And one of his aids confidently predicted that cancer would be licked in time for the bicentennial in 1976, while we’re still waiting. So yes, there is progress, but I think the questions that we have to ask about this progress are not scientific. They’re ethical, moral, political, sociological. [01:00:00] These are the questions we have to ask now.

Gary: Yeah, I think that’s a great summary. I think there’s a, there’s a concern that I have anyway, and that is that like when some people look at the future of medicine or have a futuristic conception of medicine, they they want doctors to play God in some way. And that’s, particularly if you look at, CRISPR technology and things like that are emerging, where there have been, there have actually been some positive results.

I think there was one cardiovascular disease group who published CRISPR technology related to A N G P LT three or something related to atherosclerosis. Basically, it took about 15 years to emerge, but basically they saw positive results by, affecting cholesterol metabolism and whatever else. So it’s one of those things where there’s clearly positives come from this, but if you’re going to bring, CRISPR technology into mainstream medicine in some way, one, obviously it’s going to be very expensive and pr primarily rich people are going [01:01:00] to benefit from it first.

And then two, you’re. Gonna be looking at questions like, do we eradicate all antenatal diagnoses? What do we screen for antenatally? What do we get rid of? What do we decide is acceptable and it’s not. And eventually we run into the problems of, you start with the low-hanging fruit that everyone says, oh yeah, we should get rid of those.

So let’s get rid of, let’s just say genes for leukaemia or CF or this, that and the other. But then you get into the more difficult questions like, okay, we get rid of, I don’t know, something related to that puts you at risk of back pain and maybe personality considerations. And I know that’s a very down the line, but it’s still a spectrum that’s there of the doctor rather than just ameliorating suffering, moving into the spectrum of determining evolutionary processes to some degree, playing God.

Seamus: Yeah, there is a danger [01:02:00] that medicine takes over every aspect of human life. And I dunno how often I’ve heard people saying, oh, we must invest more in healthcare. We must invest more in medical research. I would argue we should invest less. Yeah. Because in high income countries, at least your health is determined far more by your income, your education, and your job than it is directly by healthcare.

Healthcare accounts for only 10 to 20% of variation in health outcomes. And your health is far more determined by these other societal factors that I’ve mentioned. And every time people bang the drum saying, we want more investment in this, we want more investment in that. In healthcare, it means that something else loses out.

It means [01:03:00] that schooling greener transport, the arts, education loses out. So medicine is the sort of bully that’s taking everything on the on the plate. And it’s very hard for people to argue, actually, no, we should invest less in it. You some what? Because this seems to be this consensus that we need to keep investing more and more in medicine.

And I think we have reached peak medicine in a way. I would argue that dramatic rises in life extension would be incredibly bad for us as a species and for the globe that we happen to inhabit. I think that we should instead focus on extending. Healthcare that works throughout the planet equitably.

So for example, this global inequity in access to opiates at the end of life, the cost of fixing that is minuscule. It would be the annual budget of [01:04:00] a mid-sized American hospital would fix this global inequity in access to pain relief at the end of life. That’s just one random example. I worry about these claims of molecular biology and bio gerontology.

I’m not worried that these claims aren’t without foundation. My worry is that they are with foundation and that they will lead us down a path that we don’t want to go. And that medicine should retreat to. Core function of providing effective evidence-based low cost care, but within the context of the wider societal concerns and disuse as well.

Medicine should recognize that it has a limited role in health. Health, as I have said, is far more determined by other factors [01:05:00] than medicine. And I think doctors should once again get back to regarding the relief of suffering as their core function. So I think that our relationship with death, our relationship with medicine, the pandemic and the climate crisis are all interlinked.

And if I could think of what I would like to write about next, it would be those questions and how we are going to address them and where medicine is going to fit in with all of these other global and societal concerns. And I think that might be my next project.

Gary: So at the moment you’ve got the Lancer Commission that you’re working Oh, no.

You’ve got, you’re writing another book at the moment. What was that again?

Seamus: I’m writing a book about the history of psychoanalysis. Oh yeah. What got you interested in that actually I was in, I have been interested in psychoanalysis for [01:06:00] some years, not because I believe in psycho-analysis as a, an intervention.

I think there’s very little evidence that it does. In fact, there’s no evidence. But I’m interested in psychoanalysis as a historical phenomenon and as an intellectual phenomenon, and why Freud’s ideas became so widely accepted within the English speaking world. In particular. Now, psychoanalysis is no longer the force that it once was.

It’s no longer influential in psychiatry, but at one stage it was the dominant paradigm in American psychiatry and psychoanalysis is still very influential actually in in academic life. The people now writing from a psychoanalytic perspective are not so much. [01:07:00] Doctors and psychiatrists, but humanities, academics from, English literature, from literature, backgrounds, philosophy, sociology, and so on.

So Freud’s ideas are still incredibly powerful and influential. So I’m currently writing a book about, that’s it, about three figures in this book. One is Freud the other. The second is his biographer, a Welch born doctor called Ernest Jones, who was Freud’s most influential disciple. And he wrote the first major biography of Freud in the 1950s.

And he founded all of these psychoanalytic associations and journals, and he was very much responsible for spreading a. The Psycho, the doctrine of psycho-analysis throughout the English-speaking world. [01:08:00] The third person in this triangle is a surgeon called Wilfred Trotter. And before Ernest Jones became a psychoanalyst, before he became Freud’s apostle and disciple, his closest friend was Trotter, and there they were incredibly close friends and intellectual soulmates.

But there was this schism, this breakdown of their relationship, mainly because Trotter was. A sceptic, a scientific sceptic, and he wrote a famous book called Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War, and he went on to become a very famous and eminent surgeon. So I’m writing the history of psychoanalysis through the kind of triangular friendship of these three men.

On the one hand you have Freud whose ideas are [01:09:00] essentially speculative, they’re not empirical scientific ideas. On the other hand, you have Trotter who’s the classic scientific skeptic, and then in the middle you have Jones who’s essentially a kind of an opportunist and a disciple at heart.

And I’m telling the history of psychoanalysis as a social phenomenon by telling their story, these three men and their friendships. So it’s a 30 year period from about 1,908. To 1939. So 1,908 was the very first Congress ever, international Congress of psychoanalysis was held in Salzburg. And 1939, both Trotter and Freud died within a month of each other.

So it’s a kind of just 30 year period in, and it covers, the intellectual history of the time. How did psychoanalysis become this major force cultural force? So it’s about [01:10:00] psychoanalysis as a cultural force. It’s about skepticism, it’s about science. It’s about. Friendship, it’s about medicine.

So I’m trying to write it for the general reader. It’s not a heavy, reference heavy book about Freud’s theories or anything to do with that. I’m writing from trying to unpick why psychoanalysis appealed to so many people and in fact what it, the people it appealed to, and this is getting back to our earlier conversation, it appealed to the wealthy.

Yeah. Self-obsessed people. That’s what it, that’s how it appealed to, and the wealthy people set the cultural agenda for the rest of the world. And that’s how psychoanalysis really took hold. So that’s what I’m working on at the moment. I’m enjoying it very much. And it’s involved a huge amount of background reading and so on.

But I’ve learned a great deal and I’m enjoying it. And once I’m finished that I think I’d like to move on and. Write the [01:11:00] answer to the question I pose in the second book. Can Medicine be cured and write a book? Answering that question and maybe addressing where medicine should go over the next several decades with all of the other things going on in the world, particularly the climate crisis and our unhealthy relationship with death as a society.

So those are my projects. And so I don’t regard myself as retired. I’m just doing something different. I did clinical medicine for, 36 and a half years, and I think that’s long enough. I just wanted to do something else while I still had the energy to do it. So that’s my trajectory, as they say.

Very good.

Gary: And as a selfish question and just in case some of my classmates are listening as well, I’d, I have to ask regarding if you had a couple [01:12:00] of books that you’d recommend to a medic not like Harrison’s medicine and stuff, but a couple of books that you’d recommend a medical student read or a hopeful doctor to give them a perspective that you think is in line with your future vision.

What do you think you’d recommend other than your own books?

Seamus: Of course, other than my own books okay. Just off the top of my head books that influenced me a lot. And the book that I used to pull out from the medical library when I was fed up with studying and final made and I just wanted a break I would pull out a book by a physician called Richard Asher called Talking Sense.

It’s a collection of his essays. Asher is probably most famous for naming Munns syndrome. It was he who gave it the name Munns Syndrome. I would recommend that I would recommend medical nemesis by an Austrian [01:13:00] philosopher called Ivani Illich, published in the 19 seventies more recently.

I do think. Henry Marsh’s book Do No Harm has a lot to say about what it means for a doctor to carry responsibility. And that’s actually one of the ma your main job as a doctor is to carry responsibility. And it’s one thing I just, I didn’t know as a medical student, and his book is a meditation on what it is to Bear Responsibility.

If you can track down a copy on Amazon of Wilfred Trotter’s collected papers there, get that. It’s been out of print since the nine, since 1941, but his collected paper is now over 80 [01:14:00] years old. Have more to say about contemporary medicine than most books that have been published in the 80 years since.

So my forthcoming book, I hope, might lead to a resurgence of interest in what he has, what he had to say about medicine and what he had to say. Ha struck a chord with me. Every one of them words rang through as Bob Dylan would say. And despite the fact that it was written 20 years before I was even born and has been out to print for decades I read those essays and I thought these were fabulous.

The Lancet Commission and the value of death is available. Just Google it. The whole thing is there to read, and it is a good summary. Of a lot of the things to do with death and dying that I’ve talked about. [01:15:00] Just Google Lancet Commission value of death. It’s about 25,000 words, which would be a fairly short read, but it is a very readable summary of the issues around death and dying.

So I would recommend I would recommend that so yeah, those are the books that I think I would be telling medical students to have a look at. Yeah.

Gary: Excellent. And he, Henry Marsh is actually is, he was one of my big inspirations as well. One of my heroes. I watched a documentary about him after reading his book.

It’s I think I just found it online. It wasn’t on YouTube or anything. I don’t think it was called the English Surgeon. And it was about his time out in out in Ukraine. Cause he did a lot of volunteer work out in Ukraine with his yeah. Surgical work. And I think it actually highlights a lot of the things that we discussed in this conversation about how there’s such massive global inequality and access to different services that [01:16:00] he’s doing an awake craniotomy and it’s effectively in what looks like a kitchen compared to a modern neurosurgical centre.

And yeah, just people who are. Coming into his clinic with tumours that had they been spotted five years ago would have been curable, but are now terminal. And yeah, I think it’s really fascinating to get that insight into other parts of the world. So yeah, they’re great recommendations.

Seamus: Yeah. I think his it’s a very grown up book and it could only be written by somebody at the end of a career.

And where he is, he takes on these difficult thoughts about where things went wrong. Yeah. And how when things go wrong, then that stays with you as a doctor. You can’t just vanish or magic it away. And I think he’s very candid and moving actually about that responsibility.

And. Friend of mine who would be [01:17:00] contemporary of his, a very eminent friend of mine who said, don’t be telling, the medical students about a supposed golden age of your youth. Tell them instead about your worst mistakes. And Henry Marsh told this story where he was given a visiting professorship at some American medical school and they said, oh, come over and give our annual lecture, which he did.

And the title of his annual lecture was My Worst Mistakes. So he spoke for an hour on cases where things had gone disastrously wrong and where he had failed and why he had failed. And he said at the end of the his talk, the neurosurgeons local, they were all sat in the front row. Stony silence, no applause, nothing.

And I think that’s a sums up that we in medicine don’t want to address this fact [01:18:00] that, we’re human, we’re going to make mistakes. And and I think it’s a very, it’s a very salutary, healthy thing to think about. And it’s things, it’s a thing that I’ve thought about a lot since I stopped working.

Clinically, you, these things go with you to the grave and Marsh quoted a French surgeon who said every surgeon carries around in their brain a cemetery of their mistakes. I think that’s a good way of putting it. So maybe someday I’ll give a lecture like Henry Marshall, my Worst Mistakes.

But I think you did a lot of chutzpah to do that, but someday I’m, yeah.

Gary: Yeah. He’s a fascinating character because not only, I think in that book, he doesn’t just talk about the medical mistakes, but he also talks about his own character flaws and things that led to his divorce. And he talks about, he gives a story about, I did know, did he catch one of [01:19:00] his junior doctors up by the throat?

And all these types of things. Like he doesn’t present himself as being this magical hero, hysterical surgeon. He’s I’m arrogant. I make mistakes. I’m rude. Yeah. Un

Seamus: unapologetic about it. Yeah. Yeah. No, I thought his book had the Ring of Truth. Yeah. Yeah.

Gary: So yeah, look, Seamus, that’s more than what I wanted to get out of the conversation.

Really enjoyed it. I think something that’s fascinating as well, I related to Henry Marsh again, is that all people like yourself, people like Henry Marsh, there was another what’s the other neurosurgeon? Paul Callen Kana. That the breath comes air. All the, all these people, there seems to be a trend between contemplative doctors, let’s say, that have had exposure to the humanities and to the softer subjects rather than just the harder sciences.

It seems to be something that is a consistent thread. Is that something that, that you think. [01:20:00] Affected you because obviously yes, you seem to be a voracious reader and everything.

Seamus: Yes. I think I’m a slight problem with this idea or concept of the medical humanities because it’s all been taken over by this kind of, notions about, narrative medicine and teaching empathy.

And I, I think this is all bogus personally, but what I do believe is valuable and what you’ve alluded to is that I think if you have a cultural, an intellectual hinterland, then that will inform your practice as a doctor and it’ll make you see your work within a wider societal context. And I think that if I were to teach medical humanities, then that is the model that I would employ.

So I think that the medical humanities should give the students. This hinterland and it should give them [01:21:00] perspective medicine is not, a sealed world on its own. It’s part, we are part of a wider society and we, what we do has implications far beyond the hospital and the clinic and the GP surgery.

As I’ve mentioned, we live and work in a society not within a healthcare. And I think that’s what the medical humanities might be about. And it might be about asking these difficult questions that I’ve posed about where do we go with molecular biology and bio gerontology? What do we want as a species?

What should medicine do facing into this century of climate crisis? So I don’t think the medical humanities should be about, Does reading poetry make you more empathetic? I think it should be answering and asking these difficult questions and giving you a wider perspective about the work that you’ll be [01:22:00] doing.

So those I think there’s a pressing need for that kind of education amongst medical students. I think there’s a pressing need also for education about evaluating evidence. I’m not talking about statistics, I’m talking about, this was a big theme of the, my second book was where evidence and medical research, Has gone badly wrong.

And that’s not just me. There is a consensus within, the medical establishment, that medical research in terms of replication, in terms of the whole process has gone badly wrong. And thi this is another major issue I think that medical students need to be aware of and need to read about.

And I’m not sure that is happening. I think that we’ve lost somehow the knowledge amongst all [01:23:00] the information. Your generation is drowning in know information, but there’s knowledge is getting lost somewhere.

Gary: Yeah. And I think that’s something that I’ve found difficult during medical school because I enj I enjoy reading broadly and I’m, interested in things like, the philosophy and some of the humanities and things like that.

And I think, like you say it’s informed my perspective on the world to a great degree, but. When I think about my workload as a medical student it’s the classic example of the fire holes that’s just being pointed at you of, we have to learn ridiculous depth about, biochemistry and molecular biology in first year and physiology and anatomy and all this sort of stuff.

Lots of, which is incredibly useful. But when you, like you think about the amount of pharmacological facts that I’ve already forgotten, and biochemical facts that I’ve already forgotten. And unless you do a fellowship in oncology, you probably won’t, end up coming across them again. Yes.

You can’t remember it all there. There’s absolutely [01:24:00] no way. No, and I think that’s something that a lot of students are observant enough to recognize these days. Like we talked, I talked to my classmates and they say what we study and what we use or observe in the wards are totally different things.

And I think the broader education that gives you your hinterland, as you say, is something that’s potentially are almost certainly even more valuable than learning about. The different checkpoint inhibitors in the cell cycle and stuff like that. Absolutely.

Seamus: Yeah. I think medical education should withdraw to a core of things that will stay with you for a career.

And you must remember that okay, I had a career of 36 and a half years at the frontline. Your career is likely to be 56 and a half years. So you are going to have things that will sustain you through five decades of a career in medicine. And they’ve gotta be, that’s not going to be a whole wealth of biochemical, physiological or pharmacological detail that will go out of your head in six [01:25:00] months.

That’s gotta be skills and attitudes that will stay with you for decades. And I think that’s where medical education might need to recalibrate itself.

Gary: Yeah, it’s a difficult one cuz again it’s one of those things where as soon as you start to pose that question, you have to then be selective and say, this is what we’re going to remove.

This is what we’re going to remove. And every respective doctor who would be in charge of that decision making process is going to say, oh no, you need to keep in that biochemistry because yeah. We use a lot of that.

Seamus: Sorry. Yeah. Yeah. My disease is better than yours. Yeah. Yeah.

Gary: Like the, if we were to do biochemistry, we’d have to remember all the lysosomal storage diseases because paediatricians or geneticists are familiar with them.

Yeah. Yeah. Gone in a week’s time. But anyway, I won’t keep you any longer. Thank you very much for this conversation. I really appreciate it. Pleasure. Yeah. For the listener where can they find more about your work? I’ll link your books and stuff below anyway, but is there a, have you centralized?

Seamus: I have a website. A [01:26:00] website. Just Google, just Seamus. So I have a website and you can find my books my articles both. General sort of media articles, med journal articles, everything. It’s all there. I’ve written a lot for an online literary magazine, the Dublin review of books over the years.

This has got links to all of those. I write regularly for the medical independent. This links to all of those and there’s links to all my books and so on. So that has everything. Yeah. Yeah. Excellent.

Gary: So that’s Seamusomahony.com, is that what you said? Yeah. Perfect. Okay, so for the listener, we’ll be back again next week.

Myself and Paddy, and that’s Seamus. You can visit his website and I hope you enjoyed this conversation.

Join the Email List

https://forms.aweber.com/form/77/857616677.htm

Interested in coaching with Triage?

Email info@TriageMethod.com and the Triage Team will get back to you!

Or you can read more and fill in a contact form at https://triagemethod.com/online-coaching/

Interested in getting certified as a Nutrition Coach?

Check out our course here: https://triagemethod.com/nutrition-certificate/

Have you followed us on social media?

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCzYO5nzz50kOAxo6BOvJ_sQ

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/triagemethod/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/triagemethod/