Online calorie and macronutrient calculators can be quite helpful for giving you a rough idea of where your calorie and macronutrient targets should be. They certainly aren’t perfect, and they should be taken as a rough estimate to help point you in the right direction. You see, no calorie and macro calculator is going to give you the absolutely perfect and tailored dietary prescription that you actually want. Life is far too messy for that, and there really is no way for a calculator that is based on averages to give you perfectly tailored calorie and macro targets. Many online calorie and macronutrient calculators will have you believe that what they are giving you is some super secret calorie and macro targets that will allow you to effortlessly get the results you want, and this is just not helpful. In fact, I would argue that it is actually harmful rather than helpful.

I am sure you know someone who has (or perhaps you have yourself) used a calorie and macronutrient calculator and taken the figures provided as gospel. They follow the numbers as diligently as they feasibly can, and yet, they fail to get the results that they want from the diet. They then end up feeling like they have wasted a load of time, and that they have been deceived about what they should be focusing on with the diet. This then leaves them open to following much poorer dietary practices, because many of the diets that are promoted by people who are anti- “calorie and macro based diets” generally tend to be quite poorly set up.

So, instead of just providing you with another calorie and macronutrient calculator that is going to spit you out random results, I also want to spend some time discussing how you can actually interpret the results and then think about applying them to your own diet. We discussed how we generally prefer to set up someone’s diet in our foundation nutrition article, and we also discussed why we tend not to use calorie and macronutrient calculators for the article. However, that is not to say calculators don’t have their place, and this is especially true if you are trying to either gain or lose weight at a certain rate. So this calorie and macronutrient calculator also provides information on what deficit or surplus would be required to get specific rates of weight gain/loss. This can be incredibly helpful for both planning a diet and assessing whether your desired rates of progress are actually realistic.

You can get stuck into using the calculator straight away, but if you aren’t sure how to use it effectively, we do recommend reading the article in full, as it does actually answer quite a lot of the frequently asked questions and provides lots of information that will allow you to really get more out of the calculator.

Calorie and Macronutrient Calculator

Calorie & Macronutrient Calculator

| Calories and Macros | Maintenance Targets | Goal Targets |

|---|

Calorie and Macronutrient Calculator Foundational Information

Before you really get stuck into using the calculator, you generally should have some foundational knowledge in place, so you can both use the calculator properly and understand the results. A lot of this information is covered more thoroughly in our foundational nutrition article, so we really do recommend reading that if you want a more comprehensive explanation.

To understand how to use the calorie and macronutrient calculator, you do actually have to have some basic understanding of the diet first and foremost. The easiest place to start is building out a basic understanding of calories.

Calories

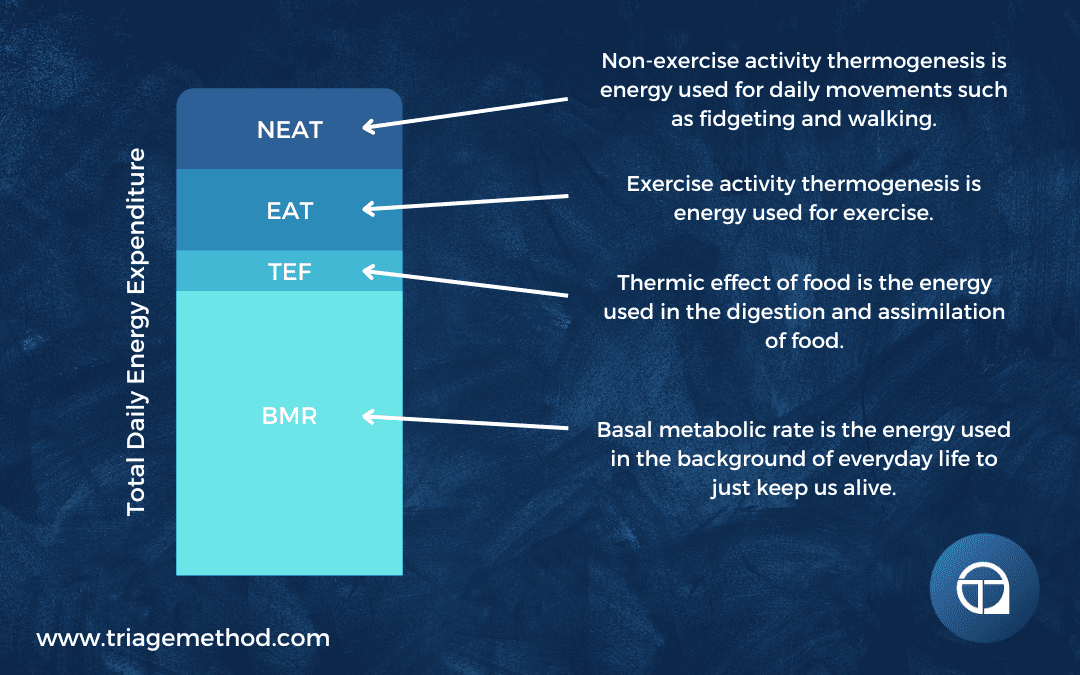

Calories are simply a unit of energy. They represent the amount of energy that our body gets from the foods we eat, and then this energy is used to power essential bodily functions, ranging from basic metabolic processes to physical activities. So when we talk about calories, we are generally talking about the energy we consume from food, and the energy we expend doing everything that we do in a day. The reason we need to eat calories is so we can fuel the activities we do each day, along with sustaining our baseline functions (such as your heart beating and lungs breathing). So, even if you are just lying in bed all day, you do actually still require calories. However, if you are more active, then you will require more calories to fuel that activity.

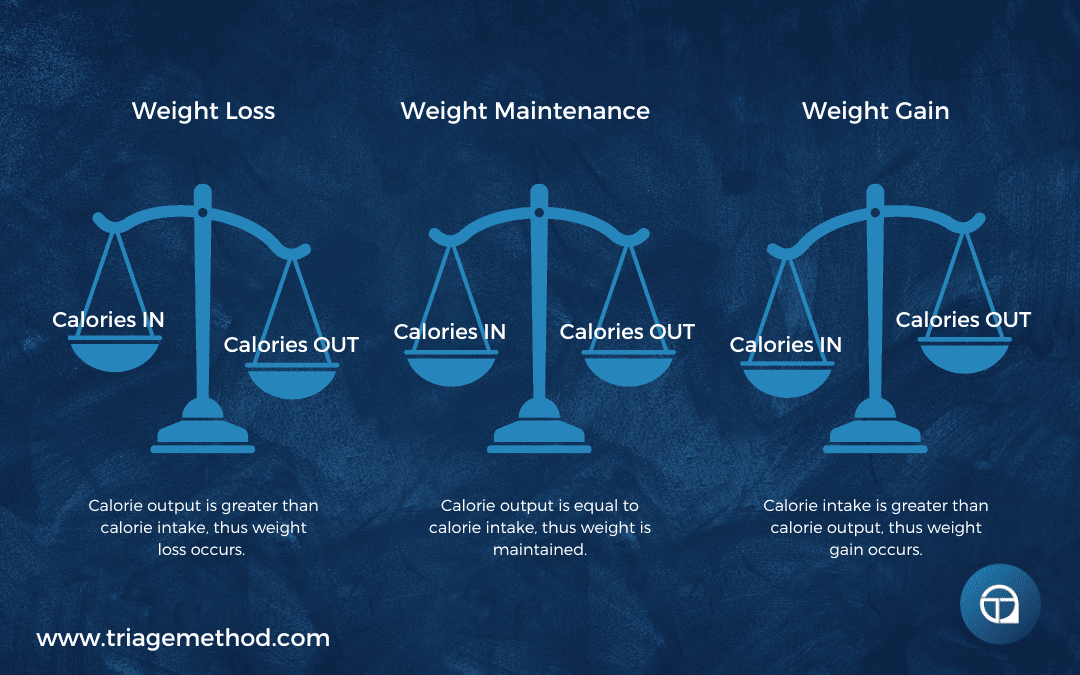

The body has the capacity to store calories, and this is mainly in the form of body fat (although some of it is also in the form of glycogen stored in your organs, and you could argue that the protein that makes up your body is also a form of stored energy). This is important to understand because it informs how we actually use a calorie and macronutrient calculator to help us get the results we desire.

You see, if you consume the same amount of calories as you expend each day, you are going to maintain your body weight. If you eat fewer calories than you burn each day, then you are going to tap into your stored energy (body fat) and you are going to lose weight. If you eat more calories than you expend each day, you are going to gain weight (this can be in the form of fat gain, or muscle gain depending on other variables in your diet and lifestyle).

This is often called the calories, calories out (CICO) equation, and you can use it to create more tailored dietary recommendations. Our calories and macronutrient calculator will calculate your maintenance calories, and then you can also choose your goal (desired goal and rate of progress) and you will get targets for that too. We will discuss this in more depth in a moment, as it is important to also understand what is actually realistic in terms of weight loss/gain.

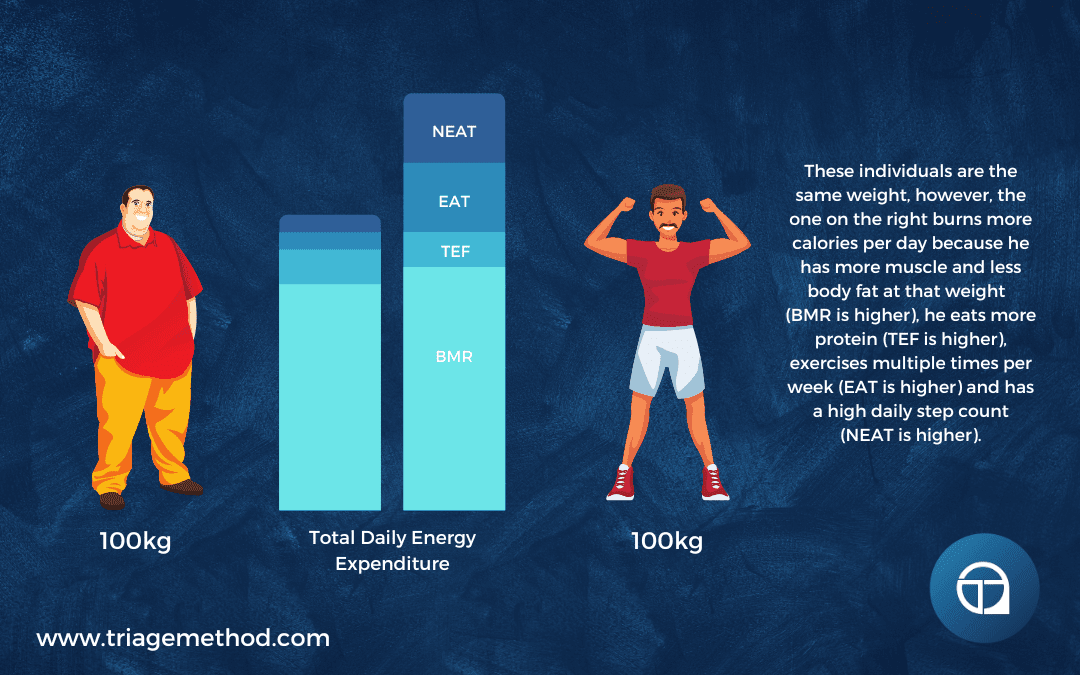

To find out your daily maintenance calorie requirements, you are generally better off using the average and adjust method we describe in our article on how to set up a diet. However, I do understand that many people just want to find out roughly how many calories they should be eating, rather than spend time tweaking their diet until they find the right amount. So using a calculator can be quite helpful as a starting point, but it isn’t as scientific as you would initially think. It is just based on averages, and depending on what you input, you can get an output that isn’t really aligned with your actual needs. This is especially the case when you have either high or low amounts of muscle mass, as muscle is more calorie-demanding than body fat. For example, if two people put in their weight as 80kg but one of them is 5% body fat and the other is 30% body fat, the calculator will tell them that they have the same calorie requirements. However, this is not the case in the real world, as the person with more muscle will generally have a higher calorie requirement.

This is further compounded by the fact that we also have to account for activity levels. As we noted previously, your calorie requirements are based on the energy your body needs to not only carry out baseline functions, but also to fuel the requirements of the activities you engage in daily. This is accounted for in our calorie and macronutrient calculator by applying an activity multiplier. The calculator first calculates your calorie needs as if you were basically not moving all day, and then it multiplies that figure based on your activity level.

These activity multipliers are as follows:

- Sedentary 1.2

- Lightly active 1.37

- Moderately active 1.55

- Very active 1.75

- Extra active 1.9

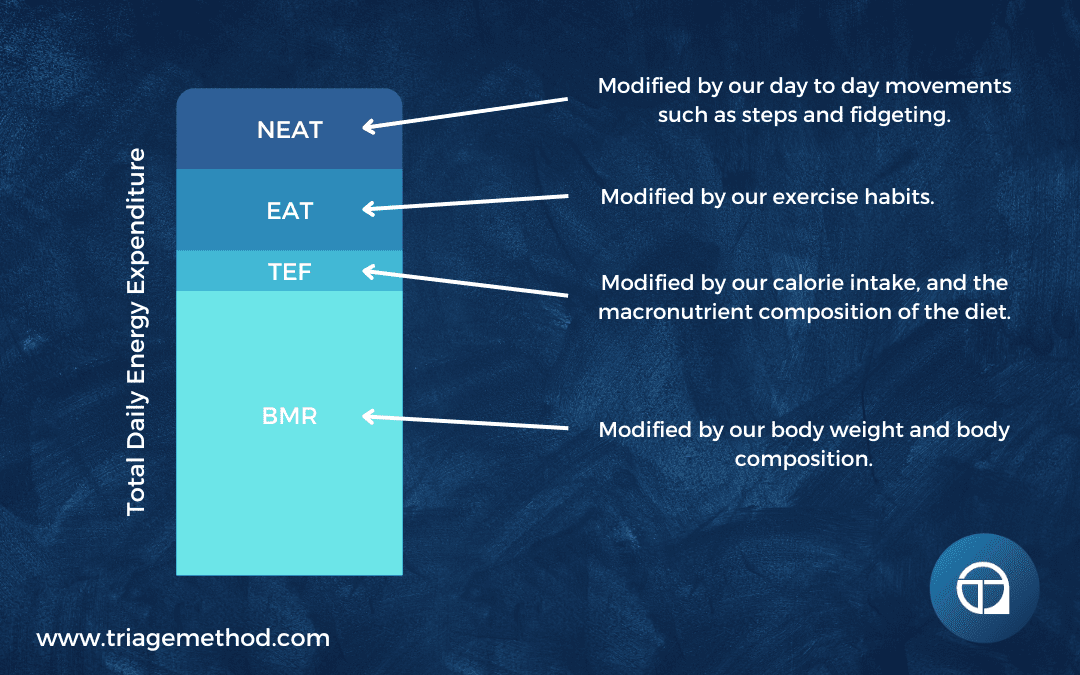

These activity multipliers are meant to capture all of your daily activity, and in doing so, give you a more accurate reflection of your actual calorie needs. However, most people are simply terrible at accurately assessing their activity levels, and thus they don’t select the correct multiplier. Most people are simply unaware of how inactive they actually are, especially as they fail to take into account non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)(you can use daily step count as a rough proxy for NEAT).

Most people will do maybe 3 gym sessions per week, and as a result, they will select “moderately active” or potentially even “very active”. Now, relative to their peers, they may actually feel like they are way more active than the average, and thus they think they should select “moderately active” at the very least. However, someone who goes to the gym maybe 3 times a week, with little activity outside of that is probably somewhere between sedentary and lightly active, rather than moderately active or above.

This is where most people go wrong when using an online calorie and macronutrient calculator. They simply select the wrong activity level and thus, they get recommended a much higher calorie amount than they actually require. Most people are generally way less active than they think they are, and most people overestimate how many calories they burn with purposeful exercise (exercise activity thermogenesis, EAT) and underestimate how many calories are burned via NEAT (daily step count). So someone who goes to the gym 3 times per week will think they are way more active than they are, while someone who gets 10,000 steps or more per day will generally underestimate how active they are. It is important to keep all of this in mind when using the calculator, as the activity multiplier is the place where most people go wrong.

In general, I tend to discuss the activity multipliers with the following guidelines in mind:

| Gym | Cardio | NEAT (Daily Steps) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary | 0 | 0 | <5,000 steps |

| Lightly Active | 3 | ≤1 | <5,000 steps |

| Moderately Active | 3+ | 1-2 hours | 5,000-7,500 |

| Very Active | 3+ | 2+ hours | 7,500+ |

| Extra Active | 3+ | 3+ | 10,000+ |

These aren’t rock solid, and there are gradations with them. Various combinations of gym training, cardio training, and NEAT can all add up to a specific activity level, and they aren’t always as clear as you would ideally like. For example, you could do no cardio but train in the gym 6 days per week for 2 hours each time, while also having a low daily step count, and still only end up with a calorie expenditure that is the equivalent of a moderately active multiplier (this is especially true if you take long rest periods and stay seated in between your sets). Alternatively, you could do 3 hours in the gym per week, and have a job that has you doing low level activity all day, and even though you don’t feel like you are exercising excessively, you could actually end up being in the “very active” to “extra active” category (for example, I have had clients who work as nurses, surgeons, postmen, warehouse workers, retail workers and a variety of other jobs that you wouldn’t necessarily think have a super high-calorie requirement, but these people very often do end up with higher calorie output by virtue of the accumulation of the low-level activities they do all day).

Using myself as an example, I currently get about 7500 steps per day, do about 270 minutes of hard resistance training and 270 minutes of hard BJJ training per week, and outside of that, I pretty much sit at a desk all day. Now, you may think that is quite an active lifestyle, and yet my actual maintenance calorie requirements are the equivalent of someone who inputs my data and selects moderately active. I have previously worked in a gym where I taught some spin classes, did lots of walking around and helping people out on the gym floor, did my own training and cycled to and from the gym each day, and my calorie requirements were over double what they are now. Even if I was to select the “extra active” multiplier, it wouldn’t give me enough calories to even maintain my weight (it underestimated my calorie requirements by over 1,000 calories)(Realistically, this could be solved with an additional activity multiplier for those that are extremely active, but this is much more rare than people think and generally only applies to athletes or those who do lots of very hard manual labour). This is why it is so important to really pay attention to what activity multiplier you choose, and then how you choose to actually interpret the results of the calculator.

This is why we generally recommend most people be a bit more conservative with the activity multiplier you choose if you are doing a normal amount of activity per week, and if you are at either end of the extreme (either lots of movement or very little movement), you should be a little bit cautious in how you interpret the calculated figures. This is why we generally prefer the average and adjust method for figuring out where your calorie requirements actually are, as it lets your body do the calculations and you just need to interpret the outcome (i.e. assess your body weight change and energy levels). If you do choose to base your diet purely on the figures given by the calorie and macronutrient calculator, please do realise that these are just a starting point and you will have to adjust them based on your real-world results. If you need help with this, then we would generally recommend getting coaching, as it can take a while to really figure out your exact requirements.

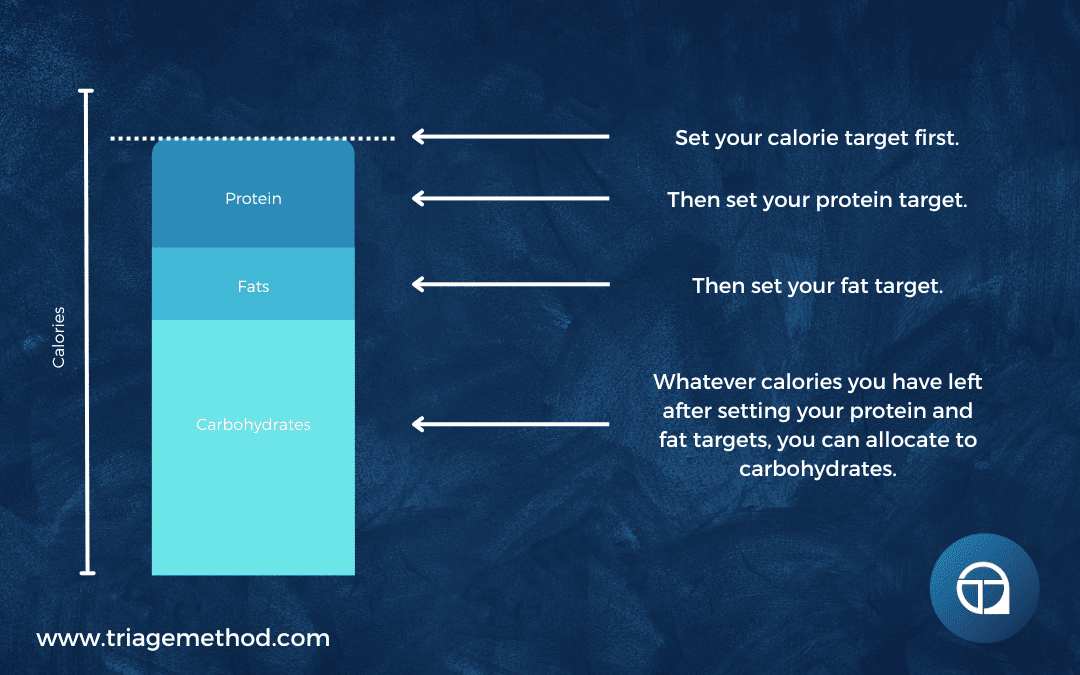

Our calorie and macronutrient calculator doesn’t just give you calorie targets, it also gives you macronutrient targets. Again, we discuss macronutrients in more depth in our diet set up article, so do read that if you want to build a better understanding of the diet. However, to be able to use the calorie and macronutrient calculator effectively, you have to have a basic understanding of macronutrients and how the calculator calculates the targets.

Protein

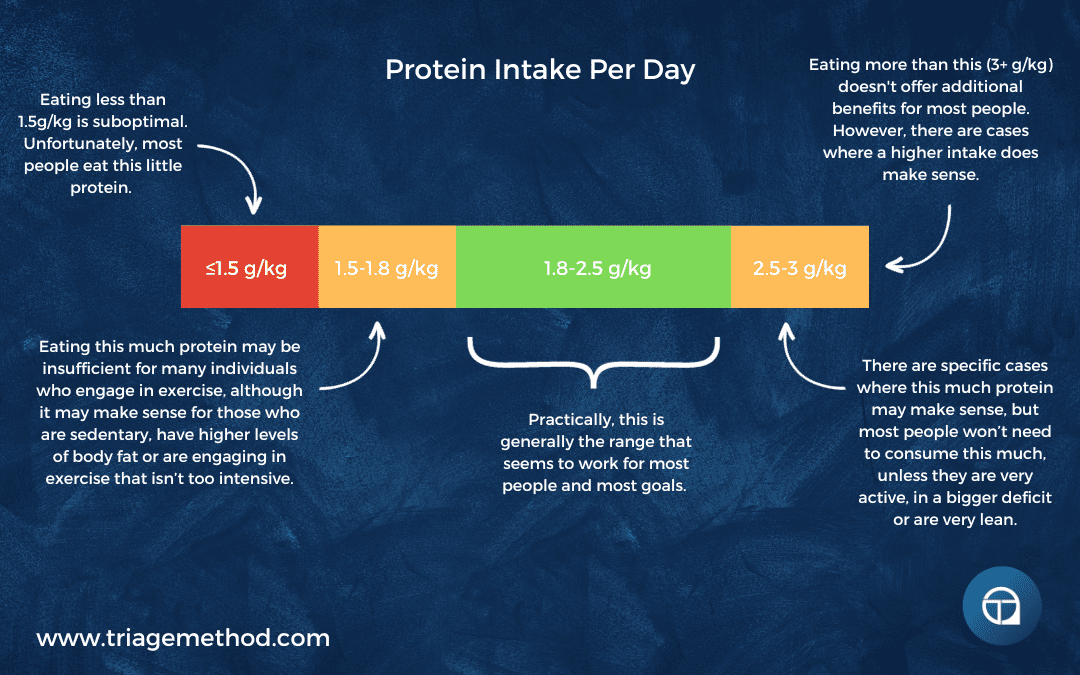

The first macronutrient we tend to discuss is protein, as it is the thing that most people likely under-consume, and the macronutrient you generally need to think more about when trying to get enough in your daily diet. Protein is an important component of your diet, as it is the fundamental building block for your body, and you need to consume it to help with building and repairing tissues. Protein is composed of amino acids, and some protein sources have a better amino acid profile than others (i.e. they contain more of the amino acids that humans need). Protein intake is important for baseline health, as it is important for immune function, and the production of enzymes and hormones. Protein is also important because it contributes to muscle development. Sources of protein include meat, fish, dairy products, beans, and nuts. The dietary recommendations for protein are generally set quite low, as they are based on older research. Newer, more accurate research suggests that higher protein intakes are required, and this is especially the case for individuals who exercise regularly. Our calorie and macronutrient calculator uses the figure of 2g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, as the target, although the range we generally recommend is between 1.5-2.5g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, depending on the specific individual and their goals. As protein contains ~4 calories per gram, we can then calculate the rest of the macronutrients based on whatever calories we have left.

Fats

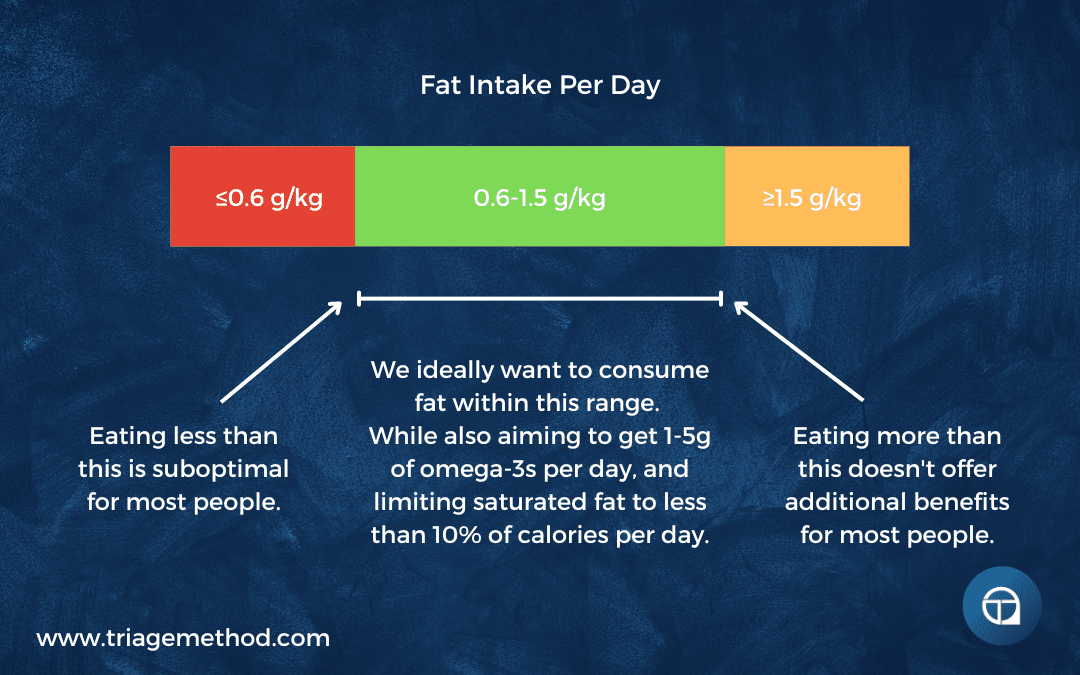

Dietary fats are the next macronutrient that our calculator calculates. Fats are an essential component of the diet as it is required to aid in the assimilation of fat-soluble vitamins, and all of your cells are actually encased in a lipid (fat) layer. Dietary fat has been vilified in many media outlets, but you do actually need to consume dietary fat for optimal health. While the thought process that eating fat will lead to fat gain seems to be self-evident (i.e. eating fat leads to fat gain), it isn’t actually accurate. Dietary fat provides calories, and a gram of fat contains 9 calories, which is more than twice the amount contained in protein or carbs. So it is very easy to overconsume calories when you are eating a lot of fat, but dietary fat isn’t inherently fat-promoting. There are a variety of fat sub-types (such as saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated), and generally, we want to try and keep saturated fat intake to less than 10% of calories, while consuming a mix of poly and monounsaturated fats. This means you should aim to consume your fats from stuff like avocados, nuts, olive oil, and leaner cuts of meat, rather than getting your fats from processed foods, fried foods or excessive quantities of butter.

Our calorie and macronutrient calculator sets your fat target as 0.6 grams of fat per kg of body weight, with a minimum intake of 20g per day. Some people may want to consume more than this, and this is more of a minimum target, rather than being set in stone. Some people do enjoy eating a diet that is higher in fats, and that can be quite health-promoting, once calories are accounted for and carbohydrates aren’t excessively low. Our calculator also gives you a target for saturated fats, so you know how much you should be consuming (it will give you a target of eating less than or equal to 10% of calories).

While the calculator doesn’t give you a recommendation for this, our general recommendation for omega-3s is to try and get somewhere between 1-5g of omega-3 per day. This can either be consumed as part of the diet by virtue of eating fatty fish, or it can be supplemented in the form of fish, krill or algae oil.

Carbohydrates

Our calculator then uses the remaining calories (once protein and fats have been set) to calculate your carbohydrate targets. Carbohydrates are the primary source of energy for the body, and they provide the fuel the body ideally wants to use to power our organs and muscles. We generally recommend that people base their carbohydrate intake around complex carbohydrates (such as grains, tubers, pulses, and fibre-rich fruits and vegetables) rather than simple carbohydrates (such as sugars and many refined products). While our calculator calculates carbohydrates based on whatever calories are left after protein and fat targets are set, you may prefer a lower carbohydrate diet, in which case, you can adjust the targets by eating more fats. Most people tend to consume quite a lot of carbohydrates in their diet, while also neglecting protein, so some people will find that they have to adjust their diet quite a bit, and mostly their carbohydrate intake, to ensure they actually get enough protein in the diet.

Fibre

Finally, our calorie and macronutrient calculator calculates fibre recommendations. Many people simply ignore fibre as a macronutrient, but ensuring your fibre intake is adequate does tend to lead to better health outcomes across the board. So understanding how much you need to consume is actually quite helpful, as adequate fibre is associated with a host of positive health outcomes and most people simply don’t consume enough. The recommendations for fibre are to consume 10-15g of fibre for every 1000 calories consumed. Our calculator calculates the fibre target as 15g of fibre for every 1000 calories consumed, so you could potentially eat a little bit less than this and still reap the benefits of higher fibre intakes. Our calculator also sets the minimum target of 25g of fibre per day, as this is generally seen as the lowest intake that should be eaten by adults.

Calorie and Macronutrient Targets

So, in summary, our calorie and macronutrient calculator is going to calculate your baseline diet as follows:

| Calories and Macros | Target Amounts |

|---|---|

| Calories | Calculated baseline energy expenditure, with activity multiplier. |

| Protein | 2g per kilogram of body weight |

| Fats | 0.6g per kilogram of body weight |

| Saturated Fat | Less than or equal to 10% of calories. |

| Carbohydrates | The rest of the available calories. |

| Fibre | 15g per 1,000 calories with a minimum intake of 25g per day. |

While you may feel that specific macronutrient ratios would be better for you, and your goals, these macronutrient ranges are generally what we recommend people start with for their diet. You do have a degree of flexibility with regard to your fat and carbohydrate targets, so you can adjust the targets yourself so that you can eat a bit more fats, and thus eat less carbohydrates. However, just because you prefer refined carbohydrates, that doesn’t mean you can adjust your protein targets down or skimp out on eating the daily fibre targets. So you do have a degree of flexibility, but it is important to try and eat a relatively well-balanced diet, with a well-balanced macronutrient profile.

Eating a well-balanced diet will generally result in better outcomes, and it will generally make actually sticking to the diet more likely. A well-balanced diet will generally lead to better appetite regulation and overall satiety, and it will also support optimal health, body composition and performance.

Personalising The Diet To Your Goals

Now, so far, we have just discussed the calorie and macronutrient calculator’s ability to work out maintenance calories and macronutrient targets. However, many of you are not simply looking to work out your calorie and macronutrient needs so you can set up a baseline diet, you are working them out so you get specific results. For most people, this tends to be to try and influence their body weight (and potentially also their body composition). So, our calorie and macronutrient calculator gives you a number of options that will allow you to adjust your targets, based on your specific goals.

However, if you are going to be using the calculator as your main method of setting up the diet, what we generally recommend is that you set your goal as maintenance, and you eat like that for at least 2 weeks. This will allow you to validate that these are actually your maintenance calories (i.e. you won’t see much if any change in your body weight), and it will allow you to set up good dietary habits and practices that allow you to actually eat in accordance with your targets. It is MUCH harder to change your diet around and try to create systems and new habits that allow you to eat a certain way, if you are also dealing with stuff like hunger. If you are very focused on influencing an outcome (i.e. weight loss or weight gain), rather than building good systems and habits, you are more than likely setting yourself up for future failure.

In our coaching practice, we see this all the time. People come to us having repeatedly struggled with dietary change, and almost every single time, they are trying to change their diet practices while also trying to eat a calorie deficit. As a result, they are simultaneously dealing with hunger and the uncertainty that comes along with not having solid systems and habits already in place. Dietary change is difficult, but if you spend time actually working on good, healthful dietary habits, rather than focusing on fat loss, it is actually much easier. So, ideally, you would set your goal as maintenance, and eat that way for at least 2 weeks. Now, unfortunately, I know you are going to read that and skip that step entirely, and go straight to selecting your desired outcome. Just realise that skipping the maintenance phase and building good habits is generally why most people struggle to stick to diets long term, and thus don’t get the results they desire.

Now, with that out of the way, you can also select goals other than maintenance. You see, as we discussed earlier, you can influence your body weight based on your calorie intake and calorie expenditure. This CICO (calories in, calories out) equation can be used to help us set up the diet in a way that either encourages weight loss or weight gain.

While it isn’t a precise science, we can come up with very rough estimates for calories based on different desired outcomes. However, just because we can come up with calorie and macronutrient targets for a given goal, doesn’t mean that the goal is actually appropriate. We could come up with calorie and macronutrient targets for someone who wants to lose 10kg in a week, but that doesn’t mean it is appropriate or advisable. As a result, you have to actually be realistic with your goals, and what is actually achievable for you right now. Appropriate goal setting is a huge part of coaching, and it is generally one of the reasons that people get much better results when they get coaching. So, without being able to be there with you to discuss your goals more thoroughly, I would generally recommend that you err on the side of selecting the options that are less aggressive. This is especially the case if you have skipped the 2-week maintenance phase that I generally recommend.

Weight Loss

Many of you will likely be using the calorie and macronutrient calculator so that you can set up your diet to facilitate weight loss. It is a very common goal, and most people are aware that getting the diet right is important for weight loss. So it is understandable that you would turn to a diet calculator to help you with this.

Unfortunately, what most people do when they try to lose weight is they try to lose as much weight as they can, as fast as they can. Most people can usually stick to a very aggressive diet for a week, and thus get very fast weight loss. However, that is usually the end of the diet, and for most people, it just ends up with them consuming more calories on the weekend and completely eliminating the calorie deficit they created during the rest of the week. The vast majority of people would be much better served taking weight loss much, much slower than they initially think is appropriate. Slow and steady really does win the race here. I know that generally isn’t what people want to hear, but I can tell you from years of coaching experience, that your success at weight loss long term is very much tied to the rate at which you lose the weight. If you take it slower, you will generally keep it off for much longer. If you go on another 6-week extreme weight loss diet, well, you will probably be doing the same again next year, and the year after, and forever forward.

While most calorie and macronutrient calculators that also offer a way to adjust your targets based on your goals will usually just provide specific absolute calorie deficits (i.e. they will set the calorie deficit by fixed calorie amounts, such as a 300-calorie deficit), we tend to use a more tailored approach to this. We generally use percentage-based recommendations for weight loss, rather than absolute calorie deficit or specific hard outcomes (such as 1kg loss per week). This tends to result in much better results, because it is actually tailored to your unique circumstances and needs. A 300-calorie deficit for someone who has a 3000-calorie maintenance requirement is much different than a 300-calorie deficit for someone who has a 1400-calorie maintenance requirement. Similarly, a rate of 1kg weight loss per week is very achievable for someone who weighs 100kg, as it is only 1% of their body weight, but incredibly aggressive weight loss for someone who weighs 55kg. So, percentage-based recommendations tend to work best.

We can reverse engineer the required deficit based on the rough approximation that 1 kilogram of body fat is equivalent to ~7,700 calories. Now, you may be thinking that surely 1kg of body fat should actually be 9,000 calories, as we said earlier that 1g of dietary fat is equal to 9 calories. And you would be right in your thinking, however, body fat, or rather what we collectively refer to as body fat, isn’t actually entirely stored fatty acids. It is a combination of fat, water, proteins and various other chemicals. So 7,700 calories per kg of fat loss seems to be relatively accurate, although there is some variation here, and there are a whole host of other variables that can confound that figure being perfectly accurate. However, as a rough approximation, it works quite well.

Using this knowledge, we can then do a bit of reverse engineering with the diet, where we can set a percentage-based rate of weight loss per week, and then roughly calculate what the required deficit would be to accomplish that rate of loss. I am roughly 100kg, so for me to lose 1% of my body weight (i.e. 1kg) as body fat per week, I would need to eat a roughly 7,700 calorie deficit across the week. This is roughly a 1,100 calorie deficit per day, spread across the week. If I were someone who weighed 80kg, to lose 1% of my body weight per week, I would need to eat a deficit of roughly 6,160 calories per week (~880 calorie deficit per day). Now, you don’t need to work this out yourself, as the calculator will do the maths for you. These calculations are never absolutely perfect, and as you begin dieting, the first week will generally see you losing weight more rapidly (due to water weight loss, stored glycogen being used up, reduced quantity of food in your digestive system and other factors), but overall, the calculations do give a very good approximation of how weight loss will go (assuming you keep your activity levels stable, and don’t start exercising less or generally moving less (i.e. your NEAT doesn’t lower)).

For most people, an appropriate rate of weight loss is somewhere between 0.5-1% weight loss per week. If you have good dietary and lifestyle habits in place, a rate of 1% weight loss can be very manageable and it is a nice balance between getting faster results (and thus not having to eat in a deficit for so long) and actually being able to stick to the diet (i.e. it isn’t so aggressive that you feel excessively restricted). However, for most people who have not had success in dieting before, or who are new to weight loss, then we generally recommend choosing a slower rate of weight loss (i.e. 0.5% weight loss per week).

For most of you, an appropriate rate of weight loss is likely going to be in that 0.5-1% per week, however, for some of you, a faster rate of weight loss may actually be the goal, and also be appropriate. It is much rarer for a faster rate of weight loss to be appropriate, but for certain populations (usually ones who already have rock-solid dietary and lifestyle habits and systems in place, have a good relationship with food and their body image is in a good place) it can be appropriate. The calculator also allows you to select an aggressive deficit that will have you losing weight at around 1.5% body weight per week. I can’t stress this enough, but for most people, this is an inappropriate goal to have, and while you may think you want to lose weight as fast as possible, in reality, you likely want to actually lose weight and keep it off long term. You will likely fail to lose the weight if you are too aggressive (as you won’t be able to stick to the diet) and you will likely fail in keeping it off long term even if you do manage to stick to the diet for any length of time (as you will likely have a worsened relationship with food, and you won’t have really solid, long term dietary habits in place).

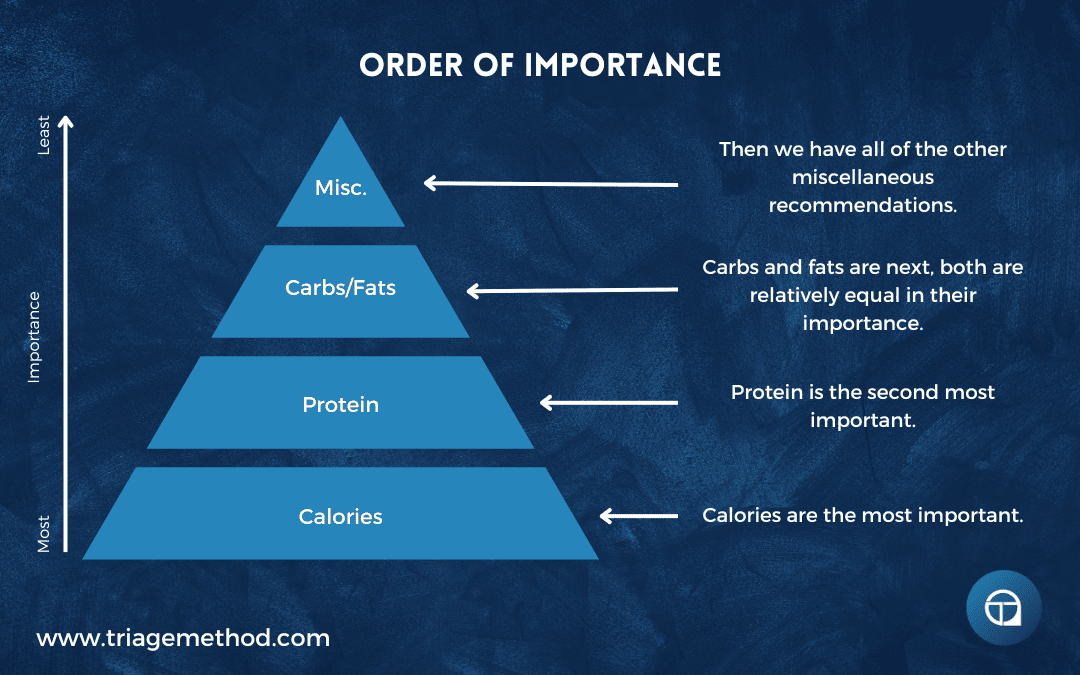

While we have been heavily focusing on calorie intake so far, it is also important to understand that macronutrients are also important. The calculator will calculate your specific targets based on the previously discussed targets, and they will be adjusted accordingly based on your specified goal. However, it is important to understand the order of priorities of the diet, when we are discussing body weight and body composition change. While calories will dictate changes in your body weight, the diet composition (and your exercise habits) will dictate the look you actually achieve at the end of the diet. Most people aren’t dieting to simply become a smaller version of themselves, they are dieting because they want to create a specific look. As a result, your exercise habits and your protein intake are very important. Exercise habits are outside of the scope of this article, but it is important to bear in mind that the calculator will give you a protein recommendation, and if you are trying to create a specific look with your body, getting sufficient protein will help you facilitate this. Protein is also very satiating and will keep you fuller for longer, and this will dramatically increase the likelihood of you actually sticking to your diet long-term. Low protein intakes are one of the major reasons people struggle to stick to diets and to actually get the results from diets. So protein is very important.

The fibre target is also important, especially for fat loss, as getting sufficient fibre will allow you to feel more satiated, and this dramatically increases the likelihood of you actually sticking to the diet. Carbohydrates and fats can be thought of as energy sources, and you can actually play around with the exact figures here (although the calculator will set the lower limit of fat intake to 20g per day, and carbs to 50g per day). There is a situation where the calculator will prioritise fats and carbs over protein, even though this is generally the reverse of what we recommend. That situation is where you have a smaller individual who is sedentary, yet wants aggressive fat loss. This is a situation which we tend not to run into quite frequently, as we generally don’t recommend people being sedentary or aggressive weight loss (and especially not both at the same time). If you are a smaller individual who is sedentary and you choose aggressive weight loss, you simply won’t have enough calories to get sufficient protein while also ensuring your fat intake is at least 20g and carbs are at least 50g. As a result, the calculator will keep the minimum fat and carb targets, and remove calories from protein to allow for that. This is a less-than-optimal situation, and again, it really is not something we recommend.

Weight Gain

Some of you may be using the calculator so that you can gain weight. Your goal may be weight gain in an absolute sense (i.e. you want to reach a specific weight) or more usually, it is because you want to gain muscle mass. Weight gain is generally a much quicker discussion, compared to weight loss, but there are some important points to keep in mind.

Firstly, while we generally discuss weight loss in terms of percentage based recommendations, it is actually a little bit easier and more appropriate to discuss weight gain in terms of absolute figures. So rather than having to do some more complex calculations and reverse engineering, all we really need to do is understand how much muscle you can gain per week/month and how many calories are required for that to occur. However, this is somewhat confounded by the fact that muscle gain is dependent on good training habits (along with good sleep and stress management habits) and it is also more variable between individuals (and even for a given individual as they become more advanced) compared to fat loss.

You can do a very quick calculation and set a deficit that will correlate with a specific rate of fat loss, and while it won’t be absolutely perfect, it will be relatively accurate. However, for weight gain, especially muscle gain, this is next to impossible. If you give a variety of different people a 500-calorie surplus, and even if you standardise their exercise routines, some of them will gain mostly muscle, some will gain mostly fat, and some of them will simply fidget more and gain no weight. It is much more fickle compared to the relatively straightforward fat loss.

Secondly, muscle gain takes an incredibly long time compared to fat loss, and it is actually much harder to achieve. While most people complain that fat loss is hard, in reality, muscle gain is much harder. You have to be much more dialled in with your diet, training, sleep and stress management to ensure muscle gain occurs, and even under optimal conditions, it occurs at a much, much slower rate than fat loss. Losing 1% of your body weight as fat could be done in a week, but gaining 1% of your body weight as muscle could take 2-6 months. Most people can stick to a diet for a week, even if it is quite restrictive. However, sticking to good dietary habits and good training practices, while also ensuring your sleep and stress management habits are dialled in, and doing that for 6 months consistently, well, it is actually much harder. The only consolation is that you do get to eat more food, although anyone who has tried gaining weight for a long period of time will attest to the fact that having to eat lots of food and continue eating beyond the point of hunger gets tiring very quickly.

So what is an appropriate rate of gain? For the most genetically gifted individuals, or for those who are newer to muscle building, a rate of gain of 1kg per month is not unheard of, or unrealistic. However, for most people, gaining 1kg of muscle per month is unrealistic, and for most, a rate of gain of less than that will be more appropriate. Now, you may be thinking that is a very low amount of muscle gain per month, and that you will be the person that is able to gain much more than this. However, I can save you the trouble of these unrealistic expectations and confirm for you that you will in fact, not be the person to gain more than this. But, if you were to actually gain 0.5-1kg of muscle per month, and do that for a year, you would have gained 6-12kg of muscle. Go into your local butcher shop and see what 6-12kg of meat actually looks like. You will see that it is actually quite a lot of mass, and even if this was spread across your whole body, it would still represent a significant increase in your muscle mass.

So for most men, gaining 0.5-1kg of muscle per month is possible, although as you become more advanced, this rate of gain does actually decrease. The longer you have been training, and the bigger you are, the lower your return on investment. For women, unfortunately, you can generally only expect about half this rate of gain. So a 0.25-0.5kg per month rate of gain may be appropriate for women. Now, the trouble is, smaller rates of gain are just very hard to track, especially if you are a woman who has a regular menstrual cycle, as there are just more swings in weight week to week.

When gaining weight, some fat gain is going to occur and this may actually be a vital part of the process. However, we do want to try to ensure that our rate of gain is not so excessive that we just end up predominantly gaining body fat. While eating more is generally enjoyable, eating an excessive surplus that has you gaining mostly fat, with only a little bit of muscle, generally just means you are going to have to diet to lose that fat in the future. We discuss longer-term dietary planning in the article on how to set up your diet, so I won’t dig further into it here. However, needless to say, generally, we want to eat a surplus that encourages mostly muscle gain while minimising fat gain (although for some populations, some fat gain is actually part of the goal, so this isn’t always the case).

As I mentioned earlier, giving percentage based recommendations for surplus’ doesn’t tend to be the best practice. So we tend to give absolute values, and while there are some issues with this method, it seems to work better in practice. To maximise muscle gain, you actually don’t need that many additional calories. If it was purely a matter of calculating the calorie content of 1kg of muscle, it would be even easier to recommend calorie targets (1kg of muscle as you experience it on your body is actually mostly water, so the calorie content is actually quite a lot smaller than you would expect). However, when we eat a surplus to build muscle, the calories are actually being used to fuel the training that leads to muscle gain, while also fuelling the recovery process. Some of the calories are also burned off by virtue of increases in general activity (NEAT). This, combined with the fact that different people will gain muscle and fat at different rates, makes it more difficult to give specific figures for how much of a surplus you need. However, what we generally do is just slowly titrate the calories up, until we find the right point where we are seeing significant improvements in training performance and our body weight is trending in the right direction consistently, and at an appropriate rate (i.e. somewhere between 0.25-1kg per month).

As a result, we generally use fixed absolute calorie increases when we are designing a diet for weight gain. Our calorie and macronutrient calculator gives you the option to choose a small surplus (150 cals), a moderate surplus (300 cals) or an aggressive surplus (500 cals). For most men, a moderate surplus is probably appropriate, while for most women, a small surplus is probably appropriate. This will need to be adjusted over time, based on real-world outcomes (i.e. are you progressing at an appropriate rate), and should only really be viewed as a starting point. If you are more advanced, a lower rate of gain is probably more appropriate, and for most, people, a small surplus for a longer period of time is generally a much better approach than a larger surplus for a shorter period of time.

The macronutrient targets will also be adjusted when you choose your specific weight gain goal. This is done via increases in carbohydrates, as carbohydrates represent the most effective macronutrient for the process of muscle gain, once calories are sufficient and baseline protein and fat requirements are taken care of. However, you could choose to spread some of the calorie surplus to fat intake, if that is your preference (generally we tend to recommend 1.5g of fat per kg of body weight per day as the top end of fat intake, although after 1g of fat per kg, most people would probably be better served eating more carbs). The fibre recommendations will scale linearly with calorie requirements, although this isn’t totally necessary and can be counterproductive. Once you get over 50g of fibre per day, it is unlikely that you are getting huge additional benefits, and eating that much fibre can make hitting your calorie requirements difficult. You generally do still need to get at least 25g of fibre per day, but if your calorie requirements are so high that you are genuinely struggling to eat enough (and you aren’t doing something like trying to eat only one meal a day or hit your entire fibre requirements in one or two meals), then you may need to adjust the fibre requirements downward. This isn’t always necessary, and I have had clients who eat 100g of fibre per day with absolutely no issues at all.

Potential Issues With The Calorie And Macronutrient Calculator

There are a few situations where the calorie and macronutrient calculator may be inaccurate. We touched on a few of these already, but I know some people just skimmed the previous content.

The calculator may be inaccurate because you selected the incorrect activity multiplier for your current lifestyle. This is generally due to overestimating how active you really are, and in general, we tend to recommend people be more cautious in what activity multiplier they select.

The calculator may also give inaccurate calorie recommendations if you are very lean or very fat. Muscle is more metabolically active than fat, so someone who is 80kg but 6% body fat will have a higher calorie requirement than someone who is 80kg but 30% body fat. For most, this simply won’t be a major issue, but it may mean that the calorie (and protein) recommendations will be slightly off for people who are at the extremes of the body fat range.

Protein recommendations are set as 2g per kilogram of body weight, but this may be inaccurate for people who are very lean, have high levels of body fat, or engage in lots of very intensive exercise. However, this generally shouldn’t be an issue, because our protein recommendations are in the middle of the recommended range (1.5-2.5g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day) and thus, you will still likely fall into a generally good ballpark figure for protein intake.

Smaller individuals who are sedentary, and want to lose weight aggressively, will also generally find that their protein requirements come out slightly differently than we would generally recommend. This is because we generally don’t recommend people be sedentary, and if they are, we definitely don’t recommend they try to chase aggressive fat loss. As the calculator sets minimum fat intake to 20g and minimum carb intake to 50g, the closer your calorie target is to ~380 calories per day, the less protein it will recommend. This is very much a less than ideal situation, and we really do not recommend selecting this option if you are a smaller individual who is sedentary (in general, we don’t recommend most people select aggressive fat loss as the goal).

Fibre intake is also set to scale with calorie intake, which can be a problem for those who have to eat higher calories, as fibre can be quite satiating. Once your fibre recommendations go over 50g per day, you can generally take them as being less of a requirement (you do still need to consume the bare minimum of 25-35g per day though!).

Metabolism Is Adaptive

This is less of a problem with the calculator and more of a feature of metabolism, but the recommendations that the calculator provides are not static recommendations. You are going to need to use real-world outcomes to adjust the diet. You see, as you increase or decrease calories, your metabolism is going to adapt to these changes over time. Some of this will be due to actually trending towards your goal (i.e. if you have lost 5kg, then the calorie deficit that you worked out initially for someone who is 5kg heavier isn’t going to be as accurate), but a lot of it will be due to changes in activity (the “calories out” side of the CICO equation). In response to underfeeding and/or overfeeding, you will generally see peoples’ energy expenditure vary quite dramatically. Some people will fidget way more when they eat more, and fidget way less when they eat less. Some will fidget more when they eat more, but not fidget less when they eat less. Some will not fidget more when they eat more, but fidget less when they eat less. And some will even fidget less when they eat more and fidget more when they eat less. This stuff isn’t a precise science, especially when we are talking about this to a larger cohort of people, rather than a specific person (it is much easier to dial things in for an individual, as you can discuss and account for many of the variables).

I wish there was an easy way around this, and while I can give some blanket recommendations, the reality is that you will just have to try to monitor your calorie intake and calorie output as best you can, and then adjust things methodically to keep things moving in the direction you want. This generally means having relatively fixed calorie intake targets that you actually stick to, and a relatively consistent exercise routine and daily step target. NEAT is the area that people tend to notice the most metabolic adaptations, so keeping your daily step count relatively standardised really does go a long way towards accounting for adaptations.

People often wonder how often they need to recalculate their calorie and macro targets and the reality is that you don’t actually need to do it frequently at all. You certainly can come back and recalculate your targets if you have lost/gained a significant amount of weight, but in reality, you should just view the recommendations that the calculator gives as a very rough starting point for the diet. You are going to have to adjust the diet based on your real-world results. I know this can be frustrating for a lot of people, especially if you are just beginning with all of this health and fitness stuff, as you just want to be given an exact plan of action, but unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Instead, you will just have to make small adjustments to the diet, to ensure things keep moving in the direction that you want. We discuss this in more depth in the article on how to set up your diet correctly.

Calorie and Macronutrient Calculator Conclusion

Hopefully, this calorie and macronutrient calculator has given you the information you need to better inform your diet set up. No calorie and macronutrient calculator is going to be perfect, but based on our coaching experience, this one does work quite well. There are some situations where you really do have to pay a bit more attention to the output data, but overall, this calculator will give you information that you can use to help you better set up your diet. It definitely should not be seen as prescriptive, and you will generally be better off getting professional help to get your diet set up correctly and fully tailored to your needs, but I do understand that getting professional help isn’t always possible. Some of you are going to want to play around with the specific macronutrient ratios, and for those of you who do, we also have a macronutrient percentage calculator.

If you would like more help with your diet (or training), we do have online coaching spaces available. if you are interested in learning more about the diet and how to coach people to a better diet pattern, we also have an Online Nutrition Coaching Certification program that may be of interest to you. We also recommend reading our foundational nutrition article, along with our foundational articles on sleep and stress management, if you really want to learn more about how to optimise your lifestyle. You can also sign up to our newsletter and YouTube channel if you wish to stay up to date with our content. You can also subscribe to our podcast on Spotify.

Calorie and Macronutrient Calculator FAQs

While this article is fairly comprehensive, there are almost always some frequently asked questions with stuff like online calorie and macronutrient calculators, so I have just collected a few FAQs here and answered them. While I have tried to answer many of the questions in the main body of this article, there are always a few questions that people want specific answers to. I will update this section if there are more FAQs.

Do I need to track calories and macros to get results?

This is a very commonly asked question, as calculating your calories and macros can leave you thinking that you have to actually utilise calorie and macro tracking daily to get the results you want. This isn’t the case. We generally recommend that people calculate their calories and macronutrients so that they have a better idea of the targets they should be aiming for, but the way you go about hitting those targets daily can look very different for different people.

In our nutrition coaching course, we teach coaches how to use our Tier System for this very question. Calculating someone’s calorie and macro targets allows you to build a better picture of what someone should be consuming, but then you have to actually come up with a method of translating those numbers into daily practices. For some people, that will be calorie and macro tracking (Tier 3), and we do generally like people to utilise this method for some time, as it really rounds out your nutrition knowledge very quickly. However, for other people, we may simply just work on their daily habits (Tier 1) to nudge their diet in the right direction. For other people, we may simply translate the calorie and macro targets into rough portion size guidelines, and just use those portion size guidelines to craft the diet (Tier 2).

So, no, you don’t need to do calorie and macro tracking to get results.

My calculated calories seem quite high/low, why is that?

This is the most common question we see when people calculate their calorie and macro targets for the first time. Some people will think that the targets are way too high and other people will think they are way too low. However, assuming you have actually chosen the correct activity multiplier, the targets are generally pretty accurate (at least as a starting point). When you get people to then actually follow the targets, they find that they do actually seem to be accurate to their needs (i.e. if they eat at the recommended maintenance calories, they do actually find their body weight is stable over time).

Depending on your previous interactions with the nutrition world, you may think that certain calorie targets are more or less appropriate for your goals. If you have been exposed to the general mass media related to diet, especially weight loss related content, you may think that a calorie intake of 2500 calories is recklessly high. Conversely, if you have been exposed to social media where people in the health and fitness community like to brag (read “lie”) about their calorie intakes, you may think that eating anything less than 1400 calories is a starvation diet or that you must eat 5000 calories if you want to gain significant amounts of muscle. So, depending on what you have previously been exposed to, you may simply have your set point for what is an accurate calorie target incorrectly calibrated.

This is why we recommend that people eat at maintenance calories for 2 weeks and see how accurately that does reflect their calorie requirements. Very often, people are shocked to find that the targets are accurate. This is especially true for those of you who have been through many rounds of yo-yo dieting, where you usually end up eating extremely low calories for a few days, and then end up binge eating. Many people think their calorie requirements are much lower than they are, because they don’t actually consistently stick to those low calories, and they also remember the lower calorie days more as they feel more restricted. But if you add up their total calories over a longer period of time, you will see that they are actually eating more than they think they are.

So, while you may think the targets are incorrect, they generally are pretty accurate, once you choose the correct activity multiplier.

My calculated protein target seems quite high/low, why is that?

Similar to the last question, many people will initially see the protein recommendations given by the calculator and either think “this is too low” or “this is too high”, depending on what they have previously been exposed to. Most people massively under-consume protein in their diet, and even getting 1g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day may be way above their general intake. Whereas other people who have been exposed to fitness content, especially bodybuilding and physique-related content may think you need to be consuming way more protein than what the calculator recommends.

We generally recommend protein intakes somewhere in the range of 1.5-2.5g per kilogram of body weight per day, as this seems to be the level of protein that is most appropriate for people who are looking to improve their health, body composition and performance. While sedentary populations can get away with lower protein intakes in the range of 0.9-1.5g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, this doesn’t mean it is optimal.

Higher intakes above 2.5g of protein per kilogram of body weight seem to not be harmful, but they also don’t seem to provide additional benefits (and potentially result in lower intakes of fats and/or carbs, which may actually hamper results).

The sweet spot for protein intake seems to be somewhere in that range of 1.5-2.5g per kilogram of body weight per day, and as 2 is smack bang in the middle of this, that is the compromise we choose for this calculator. If we were coaching you and were able to more specifically tailor your diet, this may not be the exact figure we would recommend, but it would very likely be close to it.

You provide a fibre target, but does that mean I have to track my fruit and vegetable intake?

Yes, we generally tend to recommend people track their fruit and vegetable intake, at least initially. Most people are hesitant to track fruit and veg, but in our experience, not having a fibre target and not tracking fruit and veg just leads people to under-consume fibre. By not tracking fruit and veg, people end up thinking they are eating lots of fruits and veg, but then when they actually track it, they find out that they are getting far less than they actually think. I have had clients who assured me that they eat “mountains of veg” with all their meals, and they didn’t need to track it, yet when we did, it turns out they were getting far less fibre than they thought they were getting. This is generally because people will prioritise stuff like lettuce and cucumber when adding greens to their diet. While they may end up eating quite a large volume of these, they still end up not eating enough to get sufficient fibre in the diet. By tracking fibre, you can actually get a much clearer picture of your intake and how much fruit and veg you need to eat per day. Once you have this clear picture, you can then just standardise it and not have to actively track your fruit and veg intake if you don’t wish to (you still have to eat it, and you still have to account for the calories though!).

How often should I use the calculator?

We generally only really recommend using the calculator once and using it to help you set up your diet. Then you can just adjust from there. You could potentially re-calculate your targets if you have lost/gained a significant amount of weight, but the calculator won’t provide you with more accurate information than you already have accumulated by actually dieting effectively to get the results you desire. If you want to learn more about how to set up the diet and adjust it long term, then we recommend reading the foundational nutrition article.

What if my goals change?

This may be the situation where you potentially would use the calculator again, as you may be unsure of how to adjust the diet to account for your new goals. This is especially true if you have only ever eaten a controlled diet when trying to lose weight and have never actively tried to maintain or gain weight. So yeah, you could certainly use the calculator again if you want to change your goal. We do discuss longer-term diet planning and what that looks like in practice in our article on how to set up the diet.

Can I use the calculator if I have dietary restrictions or preferences?

Potentially, yes. It is just a starting point, and can (and should) be adjusted based on your unique needs. If your dietary restrictions or preferences are food-based rather than calorie and macronutrient based, then this calculator will work perfectly fine for you, as it is agnostic to the foods you choose to eat. However, if you have specific dietary restrictions for medical reasons, we would recommend getting professional advice rather than using a calculator you found online.

Will this calculator work for plant-based dieters?

Yes, the calculator is agnostic to how you choose to hit your targets. The only real difficulty with plant-based diets is that it can be difficult to get sufficient protein, without getting excessive quantities of carbohydrates or fats in the diet, as most plant-based protein sources come along with many other macronutrients. When we coach plant-based dieters, we will generally take this into account and adjust their protein requirements down a little bit while discussing food selection methods that will allow them to get more protein in their diet. You could make an argument that due to the generally poorer amino acid profile of plant-based protein sources, you may actually have increased protein requirements. However, these issues can very easily be overcome by learning how to incorporate high-protein plant-based foods into your diet, and having a diverse array of plant protein sources in the diet.

Do I need to adjust my intake on rest days?

We generally just tend to set a standard calorie intake across all days of the week, rather than having different calorie and macro targets for each day. This tends to be easier for people to actually implement (i.e. you don’t have to tweak your food choices and diet every day depending on whether it is a high or low day), and for most people and most goals, it simply isn’t necessary to vary calorie intake daily. This is also generally accounted for with the activity multipliers, as they are based on your general weekly activity rather than daily activity. So generally, you don’t need to adjust your calories based on your activity that day, unless you end up doing way more activity than you anticipated (i.e. you went for a 12-hour hike), in which case, you may need to adjust upwards.

Can I use the calculator during pregnancy or breastfeeding?

We do not recommend you use the calculator to calculate your calorie or macronutrient needs while pregnant or breastfeeding. This is something you should get professional help with.

References and Further Reading

Bendavid I, Lobo DN, Barazzoni R, Cederholm T, Coëffier M, de van der Schueren M, Fontaine E, Hiesmayr M, Laviano A, Pichard C, Singer P. The centenary of the Harris-Benedict equations: How to assess energy requirements best? Recommendations from the ESPEN expert group. Clin Nutr. 2021 Mar;40(3):690-701. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.012. Epub 2020 Nov 20. PMID: 33279311. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33279311/

Frankenfield D, Roth-Yousey L, Compher C. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 May;105(5):775-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.005. PMID: 15883556. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15883556/

Roza AM, Shizgal HM. The Harris Benedict equation reevaluated: resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984 Jul;40(1):168-82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.1.168. PMID: 6741850. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6741850/

da Rocha EE, Alves VG, Silva MH, Chiesa CA, da Fonseca RB. Can measured resting energy expenditure be estimated by formulae in daily clinical nutrition practice? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005 May;8(3):319-28. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165012.77567.1e. PMID: 15809536. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15809536/

Speakman, J. R., Król, E., & Johnson, M. S. (2004). The Functional Significance of Individual Variation in Basal Metabolic Rate. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 77(6), 900–915. http://doi.org/10.1086/427059

Wang, Z., Heshka, S., Zhang, K., Boozer, C. N., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2001). Resting Energy Expenditure: Systematic Organization and Critique of Prediction Methods*. Obesity, 9(5), 331–336. http://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2001.42

Mcpherron, A. C., Guo, T., Bond, N. D., & Gavrilova, O. (2013). Increasing muscle mass to improve metabolism. Adipocyte, 2(2), 92–98. http://doi.org/10.4161/adip.22500

Levine, J. A., Weg, M. W. V., Hill, J. O., & Klesges, R. C. (2006). Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 26(4), 729–736. http://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.0000205848.83210.73

http://www.fao.org/3/m2845e/m2845e00.htm

Martin, C. K., Heilbronn, L. K., Jonge, L. D., Delany, J. P., Volaufova, J., Anton, S. D., … Ravussin, E. (2007). Effect of Calorie Restriction on Resting Metabolic Rate and Spontaneous Physical Activity**. Obesity, 15(12), 2964–2973. http://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.354

Redman, L. M., Heilbronn, L. K., Martin, C. K., Jonge, L. D., Williamson, D. A., Delany, J. P., & Ravussin, E. (2009). Metabolic and Behavioral Compensations in Response to Caloric Restriction: Implications for the Maintenance of Weight Loss. PLoS ONE, 4(2). http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004377

Martin, C. K., Das, S. K., Lindblad, L., Racette, S. B., Mccrory, M. A., Weiss, E. P., … Kraus, W. E. (2011). Effect of calorie restriction on the free-living physical activity levels of nonobese humans: results of three randomized trials. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(4), 956–963. http://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00846.2009

Stiegler, P., & Cunliffe, A. (2006). The Role of Diet and Exercise for the Maintenance of Fat-Free Mass and Resting Metabolic Rate During Weight Loss. Sports Medicine, 36(3), 239–262. http://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636030-00005

Goran, M. I. (2005). Estimating energy requirements: regression based prediction equations or multiples of resting metabolic rate. Public Health Nutrition, 8(7a), 1184–1186. http://doi.org/10.1079/phn2005803

Mohammad A Humayun, Rajavel Elango, Ronald O Ball, Paul B Pencharz, Reevaluation of the protein requirement in young men with the indicator amino acid oxidation technique, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 86, Issue 4, October 2007, Pages 995–1002, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.4.995

Evaluation of protein requirements for trained strength athletes. M. A. Tarnopolsky, S. A. Atkinson, J. D. MacDougall, A. Chesley, S. Phillips, and H. P. Schwarcz. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1986

Antonio, J., Peacock, C.A., Ellerbroek, A. et al. The effects of consuming a high protein diet (4.4 g/kg/d) on body composition in resistance-trained individuals. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 11, 19 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-19

Elango, R., Ball, R.O. & Pencharz, P.B. Amino acid requirements in humans: with a special emphasis on the metabolic availability of amino acids. Amino Acids 37, 19 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-009-0234-y

Marinangeli CPF, House JD. Potential impact of the digestible indispensable amino acid score as a measure of protein quality on dietary regulations and health [published correction appears in Nutr Rev. 2017 Aug 1;75(8):671]. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(8):658-667. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nux025 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28969364/

Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R, et al. Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):427-436. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4603544/

Burger KN, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, et al. Dietary fiber, carbohydrate quality and quantity, and mortality risk of individuals with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043127 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3426551/

Karl JP, Roberts SB, Schaefer EJ, et al. Effects of carbohydrate quantity and glycemic index on resting metabolic rate and body composition during weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(11):2190-2198. doi:10.1002/oby.21268 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4634125/

Chambers ES, Byrne CS, Frost G. Carbohydrate and human health: is it all about quality?. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):384-386. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32468-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30638908/

Gaesser GA. Carbohydrate quantity and quality in relation to body mass index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1768-1780. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17904937/

Gardner CD, Offringa LC, Hartle JC, Kapphahn K, Cherin R. Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults and adults with obesity: A randomized pilot trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):79-86. doi:10.1002/oby.21331 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5898445/

Astrup A, Hjorth MF. Low-Fat or Low Carb for Weight Loss? It Depends on Your Glucose Metabolism. EBioMedicine. 2017;22:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.001 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5672079/

Kim, Y., & Je, Y. (2016). Dietary fibre intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all cancers: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases, 109(1), 39–54. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2015.09.005.

Veronese, N., Solmi, M., Caruso, M. G., Giannelli, G., Osella, A. R., Evangelou, E., … Tzoulaki, I. (2018). Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 107(3), 436–444. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx082

Dietary reference intakes (DRIs). Institute of Medicine. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11537/dietary-reference-intakes-the-essential-guide-to-nutrient-requirements

2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/

Leckey JJ, Hoffman NJ, Parr EB, et al. High dietary fat intake increases fat oxidation and reduces skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration in trained humans. FASEB J. 2018;32(6):2979-2991. doi:10.1096/fj.201700993R https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29401600/

Liu AG, Ford NA, Hu FB, Zelman KM, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton PM. A healthy approach to dietary fats: understanding the science and taking action to reduce consumer confusion. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):53. Published 2017 Aug 30. doi:10.1186/s12937-017-0271-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5577766/

Zhu Y, Bo Y, Liu Y. Dietary total fat, fatty acids intake, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):91. Published 2019 Apr 6. doi:10.1186/s12944-019-1035-2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC6451787/

Lowery LM. Dietary fat and sports nutrition: a primer. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(3):106-117. Published 2004 Sep 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC3905293/

Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11:20. Published 2014 May 12. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-20 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4033492/

Pahwa R, Jialal I. Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2021 Sep 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507799/

Linton MRF, Yancey PG, Davies SS, et al. The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2019 Jan 3]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343489/

Heileson JL. Dietary saturated fat and heart disease: a narrative review. Nutr Rev. 2020;78(6):474-485. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz091 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31841151/

Clifton PM, Keogh JB. A systematic review of the effect of dietary saturated and polyunsaturated fat on heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(12):1060-1080. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.010 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29174025/

Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD011737. Published 2020 Aug 21. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32827219/

Nettleton JA, Brouwer IA, Geleijnse JM, Hornstra G. Saturated Fat Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Ischemic Stroke: A Science Update. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70(1):26-33. doi:10.1159/000455681 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5475232/

Houston M. The relationship of saturated fats and coronary heart disease: fa(c)t or fiction? A commentary. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;12(2):33-37. doi:10.1177/1753944717742549 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5933589/

Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease: modulation by replacement nutrients. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(6):384-390. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0131-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC2943062/

Hall, K. What is the required energy deficit per unit weight loss?. Int J Obes 32, 573–576 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803720

Camps SG, Verhoef SP, Westerterp KR. Weight loss, weight maintenance, and adaptive thermogenesis [published correction appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Nov;100(5):1405]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):990-994. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.050310 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23535105/

Johannsen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, Rood JC, Ravussin E, Hall KD. Metabolic slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 May;101(5):2266]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(7):2489-2496. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1444 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22535969/

Mero AA, Huovinen H, Matintupa O, et al. Moderate energy restriction with high protein diet results in healthier outcome in women. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;7(1):4. Published 2010 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-7-4 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20205751/

Phillips SM, Van Loon LJ. Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. J Sports Sci. 2011;29 Suppl 1:S29-S38. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.619204 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22150425/

Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD. Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(2):326-337. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b2ef8e https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19927027/

Stiegler P, Cunliffe A. The role of diet and exercise for the maintenance of fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate during weight loss. Sports Med. 2006;36(3):239-262. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636030-00005 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16526835/

Pendergast DR, Leddy JJ, Venkatraman JT. A perspective on fat intake in athletes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(3):345-350. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718930 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10872896/

Turocy PS, DePalma BF, Horswill CA, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: safe weight loss and maintenance practices in sport and exercise. J Athl Train. 2011;46(3):322-336. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-46.3.322 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21669104/

Helms ER, Prnjak K, Linardon J. Towards a Sustainable Nutrition Paradigm in Physique Sport: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(7):172. Published 2019 Jul 16. doi:10.3390/sports7070172 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31315180/

Iraki J, Fitschen P, Espinar S, Helms E. Nutrition Recommendations for Bodybuilders in the Off-Season: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(7):154. Published 2019 Jun 26. doi:10.3390/sports7070154 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31247944/

Paddy Farrell

Hey, I'm Paddy!

I am a coach who loves to help people master their health and fitness. I am a personal trainer, strength and conditioning coach, and I have a degree in Biochemistry and Biomolecular Science. I have been coaching people for over 10 years now.

When I grew up, you couldn't find great health and fitness information, and you still can't really. So my content aims to solve that!

I enjoy training in the gym, doing martial arts and hiking in the mountains (around Europe, mainly). I am also an avid reader of history, politics and science. When I am not in the mountains, exercising or reading, you will likely find me in a museum.