When a client asks me, “what is zone 2 training, and why is everyone suddenly talking about it?” I usually smile, because this is a topic I love to discuss.

Zone 2 is that steady, deceptively easy cardio, where you can still hold a conversation, your breathing is deeper but not haggard, and the sweat shows up after ten or fifteen minutes. It doesn’t look heroic, but it supercharges your metabolic engine.

That’s why coaches like me keep bringing it up, and why your wearable app probably nudges you toward it, and why the longevity crowd swears by it. It’s the kind of effort that builds a huge health foundation of better mitochondria, better endurance, better recovery, and more resilience. It doesn’t fry your nervous system like intervals, and it (hopefully) doesn’t leave you limping around sore the next day. You can come back to it again and again, stacking sessions, letting the benefits compound like interest in a bank account.

At first, doing this sort of cardio feels almost too easy, and you wonder if it’s doing anything. But then you realise your heart rate isn’t drifting as much, the pace you can hold at that “easy” effort is creeping up, your legs feel fresher for strength days, and daily life feels a little lighter. Stick with it for a few months, and your whole aerobic base transforms. Your resting heart rate trends down, you bounce back faster from stress, and you’ve built a buffer of durability that shows up everywhere from weekend hikes to late-night work sessions.

That’s the real reason Zone 2 is suddenly everywhere. It’s that rare kind of training that helps you look better, perform better, and age better, without beating you up in the process. You also really feel the benefits once you have been consistent for a while.

TL;DR

- What is Zone 2 training: Zone 2 is steady, conversational cardio just below LT1 (often ~60-70% HRmax). Feels “easy to moderate,” and you will usually lightly sweat after ~10-15 min.

- Why it matters: It builds mitochondria, capillaries, metabolic flexibility, and a big aerobic base, which means better endurance, recovery, resilience, and longevity without frying your nervous system.

- How to find it (no lab): Talk test (full sentences), steady nasal breathing, RPE 3-4/10, or heart rate ballpark (60-70% HRmax or MAF ≈ 180 – age). Chest straps are generally better for tracking than wrist sensors, as they are more accurate.

- What counts: Any steady modality that keeps you in-zone. Stuff like incline walk/hike, jog, cycling, rowing, elliptical, swimming, rucking, all work. Just pick a joint-friendly option that you enjoy.

- How much: 2-5 sessions/week, build from 20-30 min toward 45-90 min; ideally anchoring one longer session per week. Aim ~1.5-4.5 hrs/week for general health (more if training endurance). Progress duration first, not intensity.

- Track progress: Faster pace/higher watts at the same HR, less HR drift (>5% = too hard/under-fueled), lower resting HR, better HRV, improved health markers and daily energy.

- Who benefits: Essentially everyone. Just tailor modality, volume, and expectations.

- Bottom line: Consistent, conversational aerobic work compounds like interest, helping you look, perform, and age better without beating you up.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 What Is Zone 2 Training?

- 3 How to Find Your Zone 2 (No Lab Required)

- 4 What Counts as Zone 2?

- 5 Programming Zone 2: How Much, How Often, How to Progress

- 6 Session Structure

- 7 Resistance Training + Zone 2 (No, They Don’t Cancel Each Other)

- 8 Zone 2: Health & Longevity

- 9 Who Benefits, and How to Tailor It

- 10 Measuring Progress (Beyond “I Feel Better”)

- 11 Common Mistakes I See (And Quick Fixes)

- 12 Common Client Questions

- 13 What Is Zone 2 Training Conclusion

- 14 Author

What Is Zone 2 Training?

Zone 2 is one of those training concepts that sounds more complicated than it really is, so let’s strip it down to the essentials. At its simplest, Zone 2 is steady aerobic exercise at a “comfortably hard” effort. It’s an intensity you could hold for a long time while still being able to speak in full sentences. You’re not gasping, but you’re not just strolling either. Your breathing is deeper but under control, conversation feels possible, and usually around ten to fifteen minutes in, you’ll notice a light sweat. It should feel like sustainable work, the kind of effort you could keep going with for much longer, and you could repeat tomorrow without dreading it.

Your primary fuel at this level is fat, with a little carbohydrate mixed in. You’re working just below your first lactate threshold, at what physiologists call LT1. That’s the point where lactate starts being produced but is still cleared efficiently, so it never piles up enough to make you feel that burning, gasping “red zone”.

This is the domain where your mitochondria (the tiny powerhouses in your cells) do most of the work. When you train here consistently, you’re essentially sending those mitochondria to school. Each session teaches your cells how to burn fuel more efficiently, how to clear lactate more effectively, and how to handle a bigger workload with less strain.

Over weeks and months, the result is more mitochondria, better-quality mitochondria, improved capillary density, greater metabolic flexibility, and a stronger aerobic base. The practical outcomes are things like a lower resting heart rate, easier recovery between harder sessions, and the ability to do more without hitting a wall. Quite simply, you get fitter.

Now, it’s equally important to know what Zone 2 is not, as this is often confused. It’s not a casual walk where your heart rate barely budges. It’s not HIIT, where you blast yourself and then collapse. And it’s definitely not a secret fat-loss solution. While Zone 2 uses fat as its main fuel, body composition changes come primarily from your overall nutrition and energy balance. Think of Zone 2 as the training that builds the machinery to burn fat better, not the magic switch that makes fat melt away.

There’s also a nervous system side to this story. Training at Zone 2 encourages parasympathetic activity, which is the “rest and digest” mode that balances out the constant stress of modern life. When you spend time here, you’re not just improving endurance, you’re lowering your allostatic load (which is the accumulated wear and tear of stress on the body). Many people find they feel lighter, calmer, and more resilient after consistent Zone 2 work, not just fitter.

Zone 2 is the body’s equivalent of compound interest. Each session doesn’t feel dramatic. In fact, you might even wonder at first whether it’s doing enough. But with consistency, the modest effort accumulates, the adaptations stack up, and before you know it, you’ve built a massive engine that supports everything else, from strength training, high-intensity intervals, daily energy, and even long-term health.

Zone 2 might not look sexy on the outside, but physiologically and neurologically, it’s some of the most productive work you can do. Every time you get into that comfortably hard, conversational zone, you’re making an investment that pays you back in health, performance, and longevity.

How Zone 2 Fits Into the Models (and Why LT1 Matters)

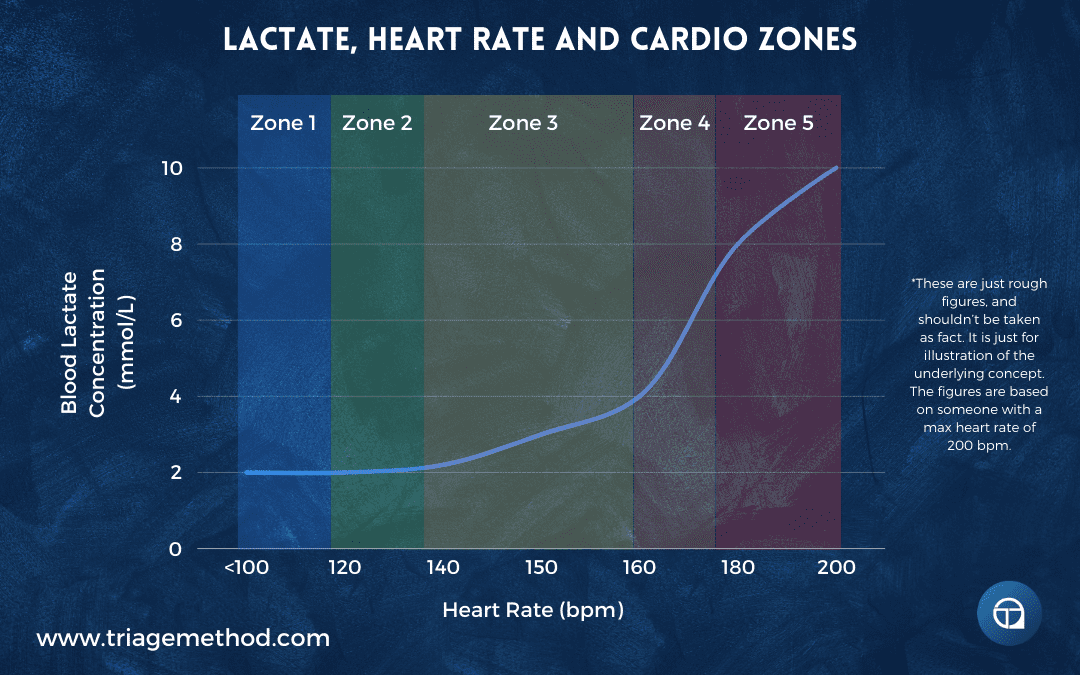

Now, if you’ve read different articles or seen your watch’s training zones, you’ve probably noticed the numbers don’t always match up. That’s because there are a few different systems for defining training zones. The good news is that Zone 2 sits in roughly the same place in all of them: just below your first lactate or ventilatory threshold (LT1 or VT1).

In physiological terms, this is the point where your body first starts producing more lactate than it can completely clear at rest, but not so much that it piles up and forces you to slow down. In a lab, that usually shows up as about 2 mmol/L of blood lactate (or roughly +1 mmol/L above baseline for an individual). That’s why Zone 2 is often called “sub-threshold” training. You’re nudging the system to the threshold, but not tipping it over.

Here’s how that maps out in the common models:

- 3-zone model (used in much of the endurance research):

- Zone 1 = below LT1

- Zone 2 = between LT1 and LT2 (but closer to the low end)

- Zone 3 = above LT2

- 5-zone model (common in cycling, running, and most wearables):

- Zone 1 = very light

- Zone 2 = 60-70% of HRmax (≈ at LT1/VT1, ~2 mmol/L lactate)

- Zone 3 = “tempo”

- Zone 4 = threshold

- Zone 5 = maximal

So if your Garmin, Polar, or Apple Watch says Zone 2, it’s essentially pointing you to that “just below LT1” effort. It’s the same steady, conversational pace we’ve been talking about. The exact heart rate number will vary depending on the formula your device uses, but the anchor is always the same steady aerobic work just under the first threshold.

This tie to LT1 is important because it explains why Zone 2 works. At this level, your mitochondria are still in charge of producing energy, and you’re training them to become more numerous and more efficient without flooding the system with lactate. That’s the sweet spot where long-term endurance and health adaptations happen.

How to Find Your Zone 2 (No Lab Required)

Finding your Zone 2 doesn’t have to involve lab coats, treadmills with tubes in your mouth, or expensive testing. In fact, most people can get very close with simple cues and a little awareness. Think of it as a spectrum of methods: good, better, and best.

At the most accessible level, you’ve got the “good” methods. These are the ones anyone can use starting today.

The classic is the talk test: if you can speak in full sentences but would struggle to belt out a song, you’re probably in Zone 2. Another quick check is nose breathing. If you can breathe steadily through your nose while exercising, you’re generally in the right range. On the perceived exertion scale, it should feel like a 3 or 4 out of 10, which is noticeable effort, but very sustainable.

The “better” methods rely on heart rate, which is where most wearables try to guide you. A common rule of thumb is 60-70% of your max heart rate, or roughly 70-80% of your heart rate at LT1 if you know it. Another simple formula that many people use is the MAF method: 180 minus your age, with small adjustments depending on your training history or health status. These aren’t perfect, but they give you a ballpark to work with.

If you want to play around with finding your own zone 2 level based on heart rate, we do have a Heart Rate Zones Calculator.

The “best” methods involve direct testing, which is how athletes and coaches dial things in. Lactate testing in the lab is the gold standard for identifying LT1. Some newer tools use heart-rate variability patterns, like DFA-alpha1, to estimate the same point without blood pricks. And of course, a full metabolic test with a professional gives the most precise picture. For the average person, these aren’t essential, but they’re available if you really want to know your exact numbers.

Knowing your zones is one thing, but then you actually have to know it in real time. There is no point knowing your zone 2 heart rate, if you have no way of measuring your heart rate in the moment. For most people, the easiest method for measuring heart rate is to just use some sort of wearable device. However, you must remember that wearables are only as good as their sensors. Optical wrist sensors can be hit-or-miss, especially if you move around a lot, have tattoos or have darker skin. A chest strap is more reliable if you’re serious about tracking.

Sometimes, heart rate isn’t even a fair guide. Stress, caffeine, dehydration, heat, altitude, or poor sleep can all push your heart rate higher than normal. On the flip side, certain medications like beta-blockers, or conditions like anaemia, can hold it artificially low. That’s why you don’t want to rely on just one metric. Pay attention to multiple cues such as your breathing, your ability to talk, your history with pace or power, and how your body feels.

It is also important to key an eye on your heart rate throughout the training session, as it can sometimes “decouple” from your perceived effort. If your heart rate drifts up more than about 5% during a steady effort (e.g., “from 130→137 bpm at same pace”), you’re either pushing a little too hard or you’re under-fueled.

Part of the value of Zone 2 is that it teaches self-regulation. You’re not just building mitochondria, you’re also building your self-awareness. The talk test, the RPE scale, and even checking in with your breathing are all forms of biofeedback. You’re training yourself to listen to your body, to notice when you’re tipping over the line, to connect effort with sensation. In that sense, Zone 2 doubles as mindfulness training.

The Stoics talked about “knowing thyself,” and Epictetus taught that awareness of your limits is a form of wisdom. Zone 2 training really embodies that principle. By practising restraint, learning the signals your body gives you, and respecting your boundaries, you build not just endurance but also the habit of tuning in to yourself. Something most people desperately need in a world that constantly pulls their attention outward.

What Counts as Zone 2?

Zone 2 can come from almost any steady aerobic activity, as long as it keeps you in that right intensity range. Walking is the most obvious choice, and adding an incline is a great way to get your heart rate up without pounding the joints. Hiking, jogging, and steady running work beautifully if your body tolerates them. Cycling, indoors or outdoors, is a classic Zone 2 modality, as is rowing. Elliptical trainers and stair mills can be surprisingly effective, and swimming (when you can keep the effort consistent) is one of the best low-impact ways to log time in Zone 2. Even weighted rucking (essentially walking with a weighted backpack) can be a fantastic and very functional way to hit the zone.

For people dealing with joint pain or back issues, there are plenty of lower-impact ways to make Zone 2 accessible. The elliptical, cycling, incline walking on a treadmill, pool running, or swimming all keep the stress off the joints while still challenging the cardiovascular system. Rowing, done with good technique, can also be joint-friendly. And if you need even more accessibility, there are chair-based ergometers, upper-body ergometers, and hand cycles, as well as pool walking. The truth is, almost everyone can find a way to train in Zone 2 safely.

However, you will more than likely need to advance things over time. I have had clients who have gotten incredibly fit, with 70+ VO2 maxes and sub 40bpm RHRs, and the level of effort they had to put in to training to get their heart rates consistently into zone 2 was actually quite dramatic, and potentially more muscularly fatiguing (thus potentially more anaerobic) than most realise. This is especially true if they were trying to get their heart rates elevated with something like cycling, as being seated makes it very difficult to really get the heart rate elevated. So this isn’t quite as clear-cut. In the beginning, you will be able to use easier modalities, but at some stage, when you are fit enough, things will almost certainly need to be progressed.

Ultimately, what counts isn’t the specific machine or activity, it’s whether you’re keeping your body in that steady, conversational effort range. From an evolutionary perspective, humans spent millennia covering ground at exactly this intensity. Walking/rucking long distances to forage, and persistence hunting until the prey tired before we did. Zone 2 isn’t some modern invention, it’s baked into our DNA.

Further to this, if you look at it through a sociological lens, moving together at this pace was also how groups bonded and survived. Fitness at this level has always been tied to belonging. While people very often mention that eating together was a bonding activity, evolutionarily, we spent way more time socialising and bonding while doing activities together. This is something that we have largely lost as a society, although with the rise of things like run clubs and exercise classes, we have gotten some of this back.

Programming Zone 2: How Much, How Often, How to Progress

Programming Zone 2 is where the rubber meets the road. Knowing what it is is one thing, but fitting it into real life is another. The good news is you don’t need a professional athlete’s schedule to make it work, you just need some consistency and a smart progression strategy.

For most general population clients, the sweet spot is two to five sessions per week. That gives you enough exposure to build the adaptations without overwhelming your calendar or recovery. In the beginning, start with 20 to 30 minutes per session. That might mean a brisk incline walk on the treadmill, a steady ride on the bike, or a jog that feels almost suspiciously easy. Over a few weeks, build those sessions toward 45 to 90 minutes. Don’t worry if that feels far away at first, like resistance training, Zone 2 is progressive. The goal is to accumulate time in the zone, not to set records every week.

When you add it all up, a good starter target is about 1.5 to 4.5 total hours per week. That’s enough to see meaningful changes in endurance, energy, and recovery. If you’re training for an endurance goal, say a long race or a big hiking trip, you’ll want to push that number higher, into the 5-7 hour range. But for most people, 1.5 to 4.5 total hours per week is a really good range. This doesn’t all have to be done at the top end of the Zone 2 range, and you can also use brisk walks alongside more specific sessions to reach the target.

Progressing zone 2 cardio is where most people get it wrong. The temptation is to push harder, but the smarter move is to extend duration before you add intensity. Your mitochondria respond to time spent working, not to spikes of effort that throw you out of the zone. I often recommend anchoring your week with one longer session. Maybe it’s a 60-90 minute jog or cycle on the weekend, or a Sunday hike with a steady effort. That “long one” becomes the cornerstone, while your other sessions fill in the gaps. Over time, we want to gradually push a bit more and nudge the ceiling higher without rushing the process.

So where does Zone 2 fit into the big picture? In the 80/20 polarised approach, roughly 80 percent of your training is easy, and most of that should live in Zone 2. The other 20 percent is where you sprinkle in intensity. In a pyramidal model, you still spend plenty of time in Zone 2, but you’ll layer in some tempo or Zone 3, and just a small fraction of true high-intensity work. But for most people, the vast majority of their cardio should be done in Zone 2.

If you’re a busy professional without hours to spare, a simple template works wonders here. Two to three Zone 2 sessions per week, plus two strength training sessions. If you’ve got extra energy, you can drop in short intervals at the end of a strength workout, but it’s not mandatory.

This is about 4 hours per week of training, which, for even the busiest of us, is not an unrealistic investment in health.

Ultimately, Zone 2 isn’t about smashing hard workouts, it’s about making those small deposits in the bank, and letting them accumulate over time. You don’t have to hit perfection every week. What matters is that you’re putting in consistent, repeatable effort that teaches your body to adapt. Over time, those small deposits of steady work compound, and suddenly you’ve built an engine that supports everything else you want to do, whether that’s running faster, lifting heavier, hiking longer, or simply having more energy for life.

Session Structure

One of the easiest ways to make your Zone 2 training more effective, and more enjoyable, is to give it some structure.

Think of your sessions as having three bookends: a warm-up, the main set, and a cool-down.

It might sound simple, but this ritualised structure does two big things. First, on the physiological side, it primes your body and nervous system so you get more out of the work. Second, on the psychological side, it gives your training rhythm and predictability. When workouts have a clear beginning, middle, and end, they feel more intentional, and habits stick more easily.

The warm-up is where everything gets switched on. Your brain and your nervous system need those first few minutes to “wake up” and sync with your muscles. In neuroscience terms, warming up improves motor cortex activation and motor unit recruitment. Basically, it makes the signals between the brain and body cleaner, so the movement feels smoother. Practically, you want about five to twelve minutes where you gradually ramp the effort. If you’re walking or running, start slower and gradually pick up the pace. If you’re cycling, start in an easier gear and build resistance. Rowers or swimmers should include some gentle drills to open up hips, shoulders, and ankles. The idea is to loosen the joints, get blood flowing, and arrive at Zone 2 smoothly instead of jumping straight into it.

The main set is where you settle into your Zone 2 effort. This is the bulk of the session. You do your steady, conversational Zone 2 work for the planned duration. To keep yourself honest, I encourage clients to do quick “micro-checks” every five to ten minutes. Can you still speak in full sentences? Is nasal breathing still relatively manageable? Is your heart rate drifting too much compared to the start of the session? These little cues help you stay in the zone without having to stare at your watch the whole time.

For runners or cyclists who want a bit of variety, it can be helpful to tack on a few short strides or pickups at the end. These are not high-intensity intervals, more like brief accelerations that wake up your neuromuscular system and add some “pop” to your legs.

The cool-down is the closing chapter, and it’s just as important as the opening one. Five to ten minutes of easy spinning, walking, or gentle movement allows your cardiovascular system to gradually downshift. More than that, it’s a signal to your nervous system to move toward parasympathetic activity (the “rest and digest” mode that promotes recovery). Long, slow exhales during this phase reinforce that downshift. Skipping the cool-down might not feel like a big deal in the moment, but over time, it makes it harder for your body to fully recover between sessions.

So the flow looks like this: ramp gradually into the zone, hold steady while checking in with yourself, and then gently return to baseline. Simple, repeatable, and effective.

Resistance Training + Zone 2 (No, They Don’t Cancel Each Other)

A common question I get as a coach is: “If I’m doing Zone 2 cardio, won’t that ruin my strength and muscle gains?” The short answer is no. When done correctly, resistance training and Zone 2 don’t cancel each other out. In fact, they complement each other in ways that make you far more capable than you’d be if you only focused on one. Strength training builds muscle, bone density, tendon health, posture, and raw power. Zone 2 builds endurance, resilience, cardiovascular health, and energy efficiency. Together, they create a body that performs better in the gym, on the field, and in everyday life, and one that continues to function well as you age.

From a health perspective, strength is non-negotiable. Lifting weights, or any form of resistance training, stimulates muscle growth, preserves lean mass as you get older, and strengthens connective tissue so your joints stay durable. It also builds bone density, which is crucial for preventing fractures later in life, and it supports posture and balance, which means you move more efficiently and with less pain. Without strength work, your body is more vulnerable to injury, frailty, and decline.

On the other side, Zone 2 training is your metabolic foundation. It strengthens the heart, improves circulation, and teaches your mitochondria to use fuel more effectively. It lowers resting heart rate, boosts recovery, and builds the aerobic base that supports everything else you do.

You can think of strength as the chassis of a car and Zone 2 as the engine, the part that actually powers the system over long distances. You’d never want a Ferrari frame with no motor, or a souped-up motor sitting in a rusted chassis. You need both.

Plato, in The Republic, described harmony between body and soul as essential to living well. He warned against being “too much of a gymnast” (all strength and bulk) or “too much of a musician” (all softness and endurance). In modern terms, we could say too much strength without conditioning leaves you stiff and fragile, while too much conditioning without strength leaves you frail and weak. The sweet spot is cultivating both power and resilience. That balance is what gives you freedom in life. The ability to lift, carry, climb, run, or play with your kids or grandkids without hesitation.

So, the real challenge isn’t deciding whether to do both, it’s figuring out how to schedule them without one interfering with the other. The so-called “interference effect” happens mostly when people combine high-volume, high-intensity cardio with heavy lifting at the same time (in the same session, or they don’t manage fatigue across the week).

But Zone 2 is different. Because it’s low-to-moderate intensity, it doesn’t produce the same muscle-damaging, glycogen-draining effect that HIIT. And once you keep the volumes manageable, and if you’re smart about how you place it, Zone 2 will actually support your strength training by improving recovery between sets, clearing metabolites more efficiently, and giving you a bigger aerobic base to handle tough workouts.

Here are the scheduling principles I give clients:

- Best case scenario: put your lifting and Zone 2 on separate days. That way, each session gets your full energy and focus.

- If you need to combine them in one session: lift first, then do Zone 2 afterwards. Resistance training relies more on fresh nervous-system output, so you don’t want to be pre-fatigued when you pick up heavy weights. Zone 2 is sustainable enough to handle being second.

- If you have two windows in a day: do strength in the morning, Zone 2 in the afternoon or evening. Splitting the work allows for better recovery and better performance in both.

When you program this way, strength and Zone 2 stop competing and start complementing. Your Zone 2 work gives you a bigger base, so you recover faster between sets and between lifting sessions. Your strength work gives you the muscle and structural integrity to perform your cardio better and stay resilient against injury. Together, they create a positive feedback loop that makes you stronger, fitter, and healthier than focusing on either one alone.

Zone 2: Health & Longevity

One of the most overlooked reasons Zone 2 training has exploded in popularity is its effect on long-term health and longevity. Athletes have always known it builds endurance, but now researchers, physicians, and coaches are recognising it as one of the most powerful tools we have for staying healthy as we age.

This isn’t a new idea. Even in the Roman era, Cicero wrote On Old Age, where he argued that cultivating health and vitality while you’re younger is what allows you to enjoy later years with dignity and strength. Zone 2 fits perfectly into that philosophy. It’s the kind of steady, sustainable work that helps you build a body and mind that still function well decades from now.

From an evolutionary psychology standpoint, Zone 2 is also the kind of movement our species was designed for. Humans survived by travelling long distances, foraging, carrying, and persistence hunting. They weren’t sprinters, although they sometimes did that too. They were doing steady, moderate-intensity efforts we could sustain for hours. Fast forward to today, and we’ve engineered most of that daily movement out of our lives. I talked about this extensively in my article on The Modern Environment Is Pathologically Sedentary. The result is we’re maladapted. Our physiology still expects regular Zone 2-level work, and when it doesn’t get it, the system breaks down.

The cardiometabolic benefits alone are reason enough to prioritise Zone 2. Consistent training at this intensity helps regulate blood pressure, improve insulin sensitivity, and shift blood lipids in a healthier direction by lowering triglycerides and raising HDL. It also reduces visceral fat, which is the metabolically dangerous fat that sits around your organs. These changes directly reduce the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, which together make up the leading causes of chronic illness and early death in developed countries.

Beyond that, Zone 2 creates a kind of autonomic balance. Many people notice that their resting heart rate trends downward and their heart rate variability (HRV) improves with regular practice. That’s your nervous system becoming more adaptable, and getting better at shifting between the “fight or flight” sympathetic mode and the “rest and digest” parasympathetic mode. In plain language, your body handles stress better and recovers from stress faster too.

At the cellular level, Zone 2 stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, where your body literally creates more of the tiny power plants in your cells that generate energy. It also improves the efficiency of the mitochondria you already have. For the ageing athlete, or really anyone who wants to maintain vitality into later life, this is wonderful. Strong, abundant mitochondria mean you’ve got more energy available for everything from training, work, family, and even just daily living. They also protect against the decline in energy metabolism that’s linked to ageing and many chronic diseases.

We also can’t forget the mental health side. Zone 2 has a uniquely restorative quality. Because it’s steady and not overly taxing, it tends to lift mood without creating a big stress response. Many people notice a calmer, more focused mental state after a session, and they are less wired than after HIIT, but more energised than after a walk. Done consistently, it also improves sleep drive, which is one of the most underrated factors in long-term health.

Put all this together, and you can see that Zone 2 is much more than “just cardio”. It’s a training practice that extends beyond performance into the very heart of healthy ageing. It builds the durability to keep doing the things you love, the energy to handle daily life with less strain, and the resilience to move into older age not just existing, but actually thriving.

Who Benefits, and How to Tailor It

One of the best things about Zone 2 training is how universal it is. Just about everyone can benefit from it, but the way you approach it should be tailored to your background, your body, and your specific goals. Let’s walk through how different groups can make Zone 2 work for them.

If you’re a beginner or coming back to exercise after a long break, the key is to start simple and keep it doable. Walking, the elliptical or cycling are excellent entry points because they’re low impact and easy to control. Start with short sessions and slowly add just a few minutes each week. The psychology here matters. Confidence comes from small, achievable wins. When you stack those wins, you build consistency, and consistency is where the real change happens.

Endurance athletes already know the value of aerobic base work, but many still make the mistake of training too hard, too often. For runners, cyclists, rowers, or swimmers, Zone 2 should be the backbone of training. At least one longer session each week should be protected at all costs. Then, layer in threshold or VO2 max work sparingly and strategically. Think of Zone 2 as the foundation that lets you actually do the harder stuff. Without it, intensity just digs holes you can’t recover from.

For lifters and team-sport athletes, Zone 2 often gets overlooked, but it’s one of the best tools for recovery and overall “engine building”. Two to three short sessions per week are plenty, and low-impact modes like cycling, the elliptical, or incline walking are smart choices because they won’t beat up the joints or compete too much with heavy lifting or explosive work. Of course, you can use sports-specific drills if you really want to, but the risk is potential overuse injuries. The payoff from the Zone 2 work is better recovery between sessions, more resilience during games, and a cardiovascular base that supports everything from conditioning drills to long practices.

Older adults may benefit more from Zone 2 than any other group, but the approach needs to be careful and joint-friendly. Swimming, pool walking, cycling, or elliptical work are all excellent because they’re easy on the joints. Warm-ups should likely be longer (10 to 15 minutes), since it takes more time for the body to “switch on” as we age. Medications also matter here, especially if they affect heart rate, so effort cues like breathing and the talk test become even more valuable than watch data.

For people with higher body weight or those who are deconditioned, low-impact options are again the safest bet. Splitting a session into two chunks (for example, two 20-minute walks instead of a single 40-minute one) can be a great way to accumulate time without overloading the body. Over time, those sessions can be lengthened and combined as fitness improves.

Women also benefit enormously from Zone 2, but programming should take into account hormonal fluctuations. Volume may need to be adjusted around high-symptom cycle days, and fueling during the luteal phase (the second half of the cycle) becomes more important to prevent dips in energy. Postpartum women should start with pelvic-floor friendly modes first (like walking, cycling, or pool work) before progressing into higher-impact options.

Finally, anyone with clinical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or those taking beta-blockers needs to be especially cautious. Zone 2 is still incredibly beneficial in these cases, but the intensity should be kept modest, and effort should be guided more by breathing and talk test than by heart rate alone. Ideally, you would coordinate with a clinician or expert coach on this.

At the end of the day, Zone 2 is very adaptable. The principles stay the same (steady, conversational aerobic work) but the application shifts depending on the person. That’s the beauty of it. No matter your age, background, or goals, there’s a way to make Zone 2 your own.

Measuring Progress (Beyond “I Feel Better”)

One of the trickiest parts of Zone 2 training is knowing whether it’s “working”. With lifting, the markers of progress are usually pretty obvious. The weight on the bar goes up, the reps get easier, or your physique changes. With Zone 2, the adaptations are happening deep inside, and you can’t really see them. Unless you have access to some lab equipment, how are you going to see whether you have more mitochondria, better lactate clearance, or a stronger aerobic metabolism?

That’s why so many people make the mistake of just repeating the same easy sessions without ever challenging themselves to progress. But just like in resistance training, if you want results, you have to track outcomes and push the needle forward.

On our program design course, we often teach the simple framework of stimulus + recovery → adaptations → outcomes. With Zone 2, you can’t easily measure the adaptations themselves, but you can track the outcomes that reflect those changes.

One of the most straightforward markers is pace or power at a fixed heart rate. Let’s say you do a steady run at 135 bpm or a steady ride at 140 bpm. Over time, if your pace per mile gets faster or your cycling watts get higher at the same heart rate, that’s clear evidence your engine is improving. A running loop, a favourite cycling route, or even a set distance on the rower can serve as your testing ground.

Another great tool is watching heart rate drift, or “decoupling.” If you hold the same pace or wattage for 60-90 minutes and your heart rate climbs more than 5%, you’re either pushing too hard or your aerobic base isn’t yet strong enough. As you train consistently, that drift decreases and your heart rate stays steady at a given workload, which means you’re becoming more efficient.

Day-to-day markers also help. A lower resting heart rate over time is a classic sign of improved aerobic fitness. Many people also notice improvements in heart rate variability (HRV), which is a marker of nervous system balance and recovery.

Health markers can reinforce the story too. Improvements in body composition, waist circumference, and blood markers like fasting glucose, haemoglobin A1c, and lipid profiles often track alongside regular Zone 2 work. These aren’t overnight changes, but over months, they paint a clear picture of better metabolic health. If you have access to a lab, VO₂ max testing is the gold standard for measuring aerobic capacity, and Zone 2 work is one of the best ways to move that number upward.

And finally, we shouldn’t overlook the subjective signs. How does the same pace or power feel over time? Does it feel easier? Are you recovering faster between days? Is your sleep improving? Do you feel more stable in energy and mood? These aren’t “soft” markers, they’re some of the most practical indicators of progress, especially if you’re training to feel and live better, not just to hit numbers.

Ultimately, Zone 2 is every bit as progressable as resistance training, but you have to actually treat it that way. Track your outcomes, celebrate the improvements, and continue nudging the volume or duration so your body keeps adapting. If you just coast along at the same pace forever, you’ll get some of the benefits, but you won’t get all the massive upside Zone 2 has to offer.

Common Mistakes I See (And Quick Fixes)

There are a number of mistakes I see very regularly with Zone 2 cardio, and most of them have easy fixes. So, let’s make sure you aren’t making these mistakes:

Going too hard (creeping into Zone 3):

This is the number one mistake. People are so used to thinking “harder is better” that they accidentally push too much and turn their Zone 2 sessions into Zone 3. The problem is that Zone 3 is too hard to give you the mitochondrial benefits of Zone 2, but too easy to give you the speed and power benefits of true high-intensity work. It’s the “grey zone” where progress often stalls.

The fix is to use the talk test (you should be able to speak in full sentences), set heart rate alerts on your watch, and check your ego. Remember: if it feels too easy, you’re probably right where you should be.

Too short or too scattered:

Zone 2 adaptations come from time in the zone. Ten minutes here and there won’t cut it beyond the beginner stages. The body needs sustained, steady exposure for the aerobic machinery to adapt.

Aim to build toward at least one longer session per week, gradually extending from 30 minutes to 45, 60, or even 90 minutes. That “anchor” session drives progress, while shorter ones fill in the week. Think quality and quantity.

Skipping strength training:

Some people fall in love with Zone 2 and ditch the weights, but that’s a big mistake. Without resistance training, you lose muscle, bone density, and joint resilience. Zone 2 will keep your heart healthy, but it won’t protect your skeleton or make you stronger.

The fix is simply to do at least two full-body strength sessions per week. Focus on squats, hinges, pushes, pulls, and core stability. It doesn’t need to be fancy, and ultimately, consistency wins. Your future knees, hips, and back will thank you.

Ignoring terrain and weather:

Heart rate isn’t just influenced by effort, it’s also influenced by the environment. Hills, heat, and humidity all spike heart rate. That’s why your usual Zone 2 pace might suddenly feel like Zone 3 on a hot day or on a hilly course. The solution is to slow down if you need to, walk the hills, move to shade, or take it indoors when conditions are extreme. Zone 2 is about internal effort, not external pace.

Comparing yourself to others:

One of the fastest ways to derail progress is comparing your numbers to someone else’s. Genetics, training history, body size, and even wearable accuracy all affect heart rate and pace. Your buddy’s smartwatch flex has nothing to do with your physiology. Track your data, use your cues, and celebrate your improvements. Progress in Zone 2 is personal.

Under-fueling and crashing:

Zone 2 feels easy, so a lot of people assume they don’t need to fuel for it. Then they bonk halfway through a session, especially if they train in the evening after a busy, underfed day. This is particularly common for parents juggling meals and kids’ schedules. The fix is to have a small snack (a banana, a piece of toast with nut butter, or a sports drink) before longer sessions, and always hydrate. Fueling properly makes sessions more productive and keeps recovery smoother.

Common Client Questions

Similarly, I often get a lot of questions about Zone 2 training, so I want to just cover them here now too:

“My heart rate is sky-high even while walking.”

This usually points to low fitness, high stress, or outside factors like heat, dehydration, or lack of sleep. Go slower, or start with an easier method of Zone 2 (elliptical, incline walking, cycling, or pool work) in a cool environment. It is also smart to prioritise sleep and hydration.

If it persists, consider whether medications (like stimulants or thyroid meds) or conditions like anaemia are playing a role. In most cases, it is just that you need to go slower, but there are conditions that can

“I can’t get my heart rate up, even when I’m working.”

This can happen if you’re on medications like beta-blockers that blunt HR response, if your warm-ups are too short or if you are just incredibly fit. The fix is to extend your warm-up, increase incline, resistance, or cadence, and avoid cooling yourself too aggressively (turn off the fan for the first 10 minutes). You may also just need to work harder than you think you do, especially if you are doing something like cycling, where you are largely seated.

If you’re on meds, use breathing and talk-test cues instead of HR as your guide.

“Zone 2 feels boring.”

For most people, this is a pretty normal experience. Zone 2 doesn’t give you the adrenaline hit that higher intensity training does. The fix here is to pair it with things you do enjoy. Podcasts, audiobooks, movies or doing it with friends. Choose scenic routes or new trails if you are able to. You can also somewhat gamify it by tracking heart-rate drift or time-in-zone, giving yourself goals to “beat” session by session. Boring work becomes a lot easier when your brain is engaged.

“My weight isn’t changing.”

Zone 2 burns fat during the session, which makes people believe that it is the key to fat loss, but fat loss depends on your weekly calorie balance. Think of Zone 2 as a tool that supports your metabolism and helps you burn calories, but it’s not a substitute for good, healthy nutrition habits. The fix here is to combine regular Zone 2 with consistent, sustainable, calorie-appropriate nutrition strategies. Together, they will contribute to the body composition changes you want.

“My legs feel heavy from lifting.”

This is common if you’re stacking Zone 2 too close to heavy lower-body training. The solution is to separate your strength and Zone 2 days when possible. If you must combine them, lift first, then do Zone 2. Or, choose a low-impact modality like cycling or elliptical the day after a heavy lower-body session. There is also an adaptation period, and things do get easier as you adapt.

“Do I really need 90 minutes?”

Longer sessions do provide unique adaptations, but they’re not mandatory. Start where you are, whether that is 20, 30, or 45 minutes, and build up. For general health, consistency matters more than hitting marathon-length sessions.

“Will Zone 2 make me slower?”

Quite the opposite. Zone 2 lays the foundation that allows you to perform and recover from speed and intensity work. Without it, speed training is like building a house on sand. You’ll hit a ceiling quickly, and risk burning out. There is a reason why most world-class athletes do a lot of Zone 2 work.

“Should I train fasted or fed?”

Both can work. Fasted training can somewhat improve metabolic flexibility, but don’t let it compromise your ability to perform or your recovery. If you’re doing longer sessions, a little fuel beforehand is usually smarter. Experiment, and see what helps you stay consistent.

“Do ellipticals, rowers, or stair mills count?”

Absolutely. The tool doesn’t matter; the effort does. If your heart rate and breathing stay in the Zone 2 range, it counts. Choose the modality that fits your body, your joints, and your lifestyle.

The bottom line is that Zone 2 rewards patience, consistency, and self-awareness. The barriers people run into are all solvable with small tweaks. If you commit to ironing those out, Zone 2 stops being confusing and becomes exactly what it should be: a simple, repeatable practice with massive long-term payoff.

What Is Zone 2 Training Conclusion

Zone 2 training might not look flashy, but it’s one of the most powerful tools you can add to your routine. It’s steady, sustainable, and deceptively simple, and that’s exactly why it works. At this intensity, you’re building the kind of fitness that produces profound results across the body. Lower blood pressure, better insulin sensitivity, improved cholesterol, stronger mitochondria, a bigger aerobic base, and a nervous system that handles stress more gracefully. You recover faster, you feel more energetic in daily life, and you set yourself up for better long-term health.

It improves health markers, boosts athletic performance, and supports longevity, without beating you up or leaving you burned out. Strength training makes you strong, intervals make you fast, but Zone 2 is the glue that holds everything together. It’s the foundation that lets all the other pieces of training stick.

Keep it easy enough to be conversational, keep it consistent across the weeks, and don’t overthink it. The “easy work” doesn’t feel heroic in the moment, but it compounds like interest in a savings account. Each session teaches your body to burn fuel better, recover faster, and go farther with less strain. Over time, those deposits of effort build a monster engine.

As with everything, there is always more to learn, and we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface with all this stuff. However, if you are interested in staying up to date with all our content, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter and bookmarking our free content page. We do have a lot of content on how to design your own exercise program on our exercise hub.

We also recommend reading our foundational nutrition article, along with our foundational articles on sleep and stress management, if you really want to learn more about how to optimise your lifestyle. If you want even more free information on exercise, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

References and Further Reading

Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242(9):2278-2282. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4290225/

Andersen P, Henriksson J. Capillary supply of the quadriceps femoris muscle of man: adaptive response to exercise. J Physiol. 1977;270(3):677-690. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011975 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/198532/

Seiler S. What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes?. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2010;5(3):276-291. doi:10.1123/ijspp.5.3.276 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20861519/

Stöggl T, Sperlich B. Polarized training has greater impact on key endurance variables than threshold, high intensity, or high volume training. Front Physiol. 2014;5:33. Published 2014 Feb 4. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00033 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3912323/

Seiler KS, Kjerland GØ. Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution?. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(1):49-56. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00418.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16430681/

Foster C, Casado A, Esteve-Lanao J, Haugen T, Seiler S. Polarized Training Is Optimal for Endurance Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54(6):1028-1031. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002871 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35136001/

Foster C, Porcari JP, Anderson J, et al. The talk test as a marker of exercise training intensity. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28(1):24-32. doi:10.1097/01.HCR.0000311504.41775.78 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18277826/

Quinn TJ, Coons BA. The Talk Test and its relationship with the ventilatory and lactate thresholds. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(11):1175-1182. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.585165 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21774751/

Rogers B, Giles D, Draper N, Hoos O, Gronwald T. A New Detection Method Defining the Aerobic Threshold for Endurance Exercise and Training Prescription Based on Fractal Correlation Properties of Heart Rate Variability. Front Physiol. 2021;11:596567. Published 2021 Jan 15. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.596567 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33519504/

Rogers B, Berk S, Gronwald T. An Index of Non-Linear HRV as a Proxy of the Aerobic Threshold Based on Blood Lactate Concentration in Elite Triathletes. Sports (Basel). 2022;10(2):25. Published 2022 Feb 18. doi:10.3390/sports10020025 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8875480/

Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e004473. Published 2013 Feb 1. doi:10.1161/JAHA.112.004473 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23525435/

Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, He J. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(7):493-503. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00006 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11926784/

Nassis GP, Papantakou K, Skenderi K, et al. Aerobic exercise training improves insulin sensitivity without changes in body weight, body fat, adiponectin, and inflammatory markers in overweight and obese girls. Metabolism. 2005;54(11):1472-1479. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2005.05.013 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16253636/

Ross R, Janssen I, Dawson J, et al. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obes Res. 2004;12(5):789-798. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.95 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15166299/

Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Roberts S, Haskell W. Comparison of aerobic exercise, diet or both on lipids and lipoproteins in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(2):156-167. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22154987/

Amekran Y, El Hangouche AJ. Effects of Exercise Training on Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62465. Published 2024 Jun 16. doi:10.7759/cureus.62465 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11250637/

Lundstrom CJ, Foreman NA, Biltz G. Practices and Applications of Heart Rate Variability Monitoring in Endurance Athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2023;44(1):9-19. doi:10.1055/a-1864-9726 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35853460/

Souissi A, Haddad M, Dergaa I, Ben Saad H, Chamari K. A new perspective on cardiovascular drift during prolonged exercise. Life Sci. 2021;287:120109. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120109 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34717912/

Shcherbina A, Mattsson CM, Waggott D, et al. Accuracy in Wrist-Worn, Sensor-Based Measurements of Heart Rate and Energy Expenditure in a Diverse Cohort. J Pers Med. 2017;7(2):3. Published 2017 May 24. doi:10.3390/jpm7020003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28538708/

Pasadyn SR, Soudan M, Gillinov M, et al. Accuracy of commercially available heart rate monitors in athletes: a prospective study. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2019;9(4):379-385. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.06.05 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6732081/

Wilson JM, Marin PJ, Rhea MR, Wilson SM, Loenneke JP, Anderson JC. Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2293-2307. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22002517/

Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2024-2035. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.681 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19454641/