The goal of this foundational stress management article is to give you a resource you can use to learn how to manage your stress using good evidence-based information and the latest science.

Stress is a topic that doesn’t get the spotlight that it deserves, and when people do discuss it, the advice that is given is usually quite vague and/or incorrect. So this article is designed to both help you understand what stress is, the impacts of stress, and then what you can actually do to manage your stress levels. We could get caught up in some relatively meaningless biochemical pathway, and you see many discussions of stress falling victim to this, but that is not what we’re going to do here. This article will give you the overview information you need to understand stress, and then also give you the information you need to actually take action to manage your stress. By the end of the article, you will have a very clear understanding of stress, and you will also have a few strategies to better manage your stress.

The article is laid out as follows, and you can jump to whichever section you feel is most important to you by clicking the link in the Table of Contents:

Table of Contents

We believe in empowerment through education, so we think it is important to have some understanding of the why behind health topics such as stress. If you understand the why, then the “how” makes a lot more sense. You don’t want to just learn about specific protocols and hope they work for you. No, you want to build a deeper understanding of the topic so that you can modify the protocols to fit your lifestyle and needs. You certainly don’t need to be an expert, but a little bit of knowledge really does go a long way with this stuff. So we will be discussing some of the science behind stress and why the basic stress management practices work, but if you simply want to know what to do with no background information, you can skip all the way down to the Stress Management section.

If you want more free information on nutrition, training, stress management or sleep, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of the diet. We also offer coaching if you need help with your own diet. Finally, if you want to learn how to actually coach nutrition and help people manage their stress, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

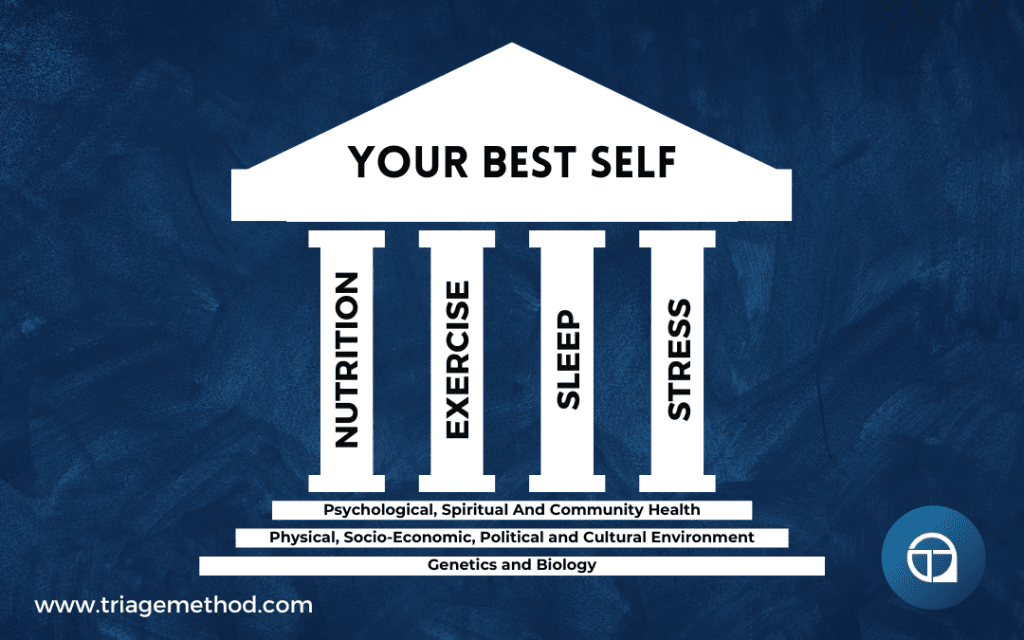

This article is part of our fundamentals series, where we discuss the key pillars of building “your best self”. Being your best self means you are able to engage with the world how you want to engage with the world and ultimately, accomplish the goals you have. Regardless of what that actually looks like for you, if you can get the pillars set up correctly, you give yourself the best opportunities to accomplish everything you want to in this life. The foundations of the broader society you find yourself in also matter, as do the genetics you were born with or the biology you were born with or acquired (your “biology” could change due to accident or injury, for example, you may have become paralysed, and thus your “biology” has changed), as does your mental and spiritual health, and of course, the health of your local community and support systems. However, much of the foundations are out of our active control, but we can work to set up the pillars as best we can, given the circumstances we find ourselves in. In this article, we discuss stress management, but we do also have an article on sleep and nutrition if you are interested in learning about those pillars, and we will discuss exercise in a future article (you can sign up to the email list to be notified when it is live on-site).

The goal of this article is to provide you with the tools you need to get a really robust stress management system in place. However, to do that, we need to dive a bit deeper into what stress is, the science of stress and to basically build out a better understanding of stress. Then we can really dig into the tips you need to improve your stress management practices. However, you can jump to this section if you just want to get straight into the stress management tactics.

What is Stress?

What is stress? We use the term a lot these days, but if you asked most people to actually describe what stress is, you would get some rather vague explanations, focused around a sort of negative type of feeling. That description is actually ok for a general discussion, and you don’t need to know all the ins and outs of stress to be able to get good stress management practices in place. However, we truly believe that you get empowered through education and thus having a basic understanding of what stress actually is, really does allow us to create better stress management strategies for your situation. Without a deeper understanding, you are left just following protocols and systems someone else devised, rather than being able to create the protocols and systems that would actually help with your own specific situation.

At a fundamental level, stress is simply the body’s response to a stressor. It is your nervous system interpreting the stimuli from the world around you, and then mounting a response to that stimulus. It isn’t inherently good or bad, it is simply a response. Stress can be incredibly beneficial, if it is helping you to mount an adequate response to a stressor like a bear suddenly appearing in front of you on a hiking trail. However, it can be incredibly negative if you are sitting at your desk with an uncontrollably high heart rate, just thinking about the various things you have to get done for work etc. So context really does matter, and further to this, there is a huge degree of individual variability with this too. What you deem a negative stress might be something that someone else thoroughly enjoys, and it causes them no negative stress feeling (this is very evident in something like public speaking where some people are terrified of it, while other people find it incredibly enjoyable and not a stress at all).

So, as you can see, stress, as we describe it in an everyday sense, is actually a bit vague. To detangle this and allow us to actually understand what stress is and how to deal with it, we do actually need to build out a much better understanding of stress. To do this, I think it makes sense to first discuss what the medical and scientific community understand stress to mean, and then bring that understanding back to the real world.

As a scientific term, in a biological context, stress is simply defined as; “stress is the body’s response to a stressor”. Now, as we have discussed earlier, this isn’t actually that helpful in the real world, as it isn’t what the average person is discussing when they discuss stress. As a definition, it does also leave a lot to be desired, as it sounds like a definition someone would give you if they didn’t actually understand the concept (it sounds very like, “stress is the feeling you get when you encounter something that causes stress”, and this would be a very poor definition if you were trying to explain the term to someone who spoke a different language). This definition isn’t very in line with what most people understand stress to be, and as a result, some branches of the scientific community (mainly neuroscientists) have tried to change the definition of stress to something along the lines of “stress should be restricted to conditions where an environmental demand exceeds the natural regulatory capacity of an organism”. This does align better with the everyday understanding of stress, but it does fall short in a number of ways, and it would require the creation of new terminology for a variety of things that we currently discuss related to stress. It also wouldn’t allow us to discuss a variety of things that we discuss related to stress that are relevant for those of us interested in health, nutrition and fitness. So I am going to use the generally accepted definition of stress, but I am going to try to build your understanding of stress to a level where you can actually better utilise this definition and understand “positive” versus “negative” stress.

So with that out of the way, I want to unpack the “stress is the body’s response to a stressor” definition.

Let’s leave the term stress alone for a second, as that is what typically causes a lot of the general confusion when trying to understand stress. Instead, let’s turn our attention to the term stressor. A stressor is simply a stimulus that is applied to the body, and realistically, you could just substitute the word “stimulus” for “stressor”. This stimulus does not even need to be physical, it can also be completely “made up” in your mind. The body is simply responding to the perceived world around it (and perception is not the same for everyone, and this also creates a lot of confusion in this discussion). The stressor is inherently neutral, and the body is mounting a response that it thinks will help it to deal with that perceived stressor. This is why novel things that you haven’t experienced before may appear to be more stressful than things you do every day. This is also why some people feel excessively stressed by certain stimuli than other people, who seem to be more resilient to the same stressors. The stressor isn’t good or bad, the body is just mounting a response that it thinks will help it deal with that stressor. The body has to interpret the stimuli that are coming in from the perceived world, and when it encounters unknown or “higher-intensity” stimuli, it responds with “alarm”. It doesn’t know what this new stimulus is, so it mounts a response that it thinks will adequately allow it to deal with this stimulus. While all of you reading this are unlikely to be extremely startled by a book falling off your desk or another startling event, there was a time when even mildly loud voices were too much of a stimulus for you and overly stressed you out. When you were a baby, even talking too loudly resulted in alarm. This is true of many other stimuli in a baby’s environment (no wonder they cry all the time). But over time, the baby dials down the responsiveness to these stimuli, and their resilience to these stimuli increases and they get to the stage where they are quite resilient to most things they are likely to encounter in the environment they live in. However, if they were to be transported to a faraway land, where they did not build resilience to the stressors present there, well, they would probably have a higher stress response again. But I am getting ahead of myself here, as I just want to illustrate that the stressor itself is relatively neutral, and it is the “stress” side of things that changes.

We have a rough definition of what stress is, but if we are to get to a point where we can create effective systems and strategies for dealing with the stress in our own lives, we have to build a better understanding of stress. So, to actually build a better understanding of stress, we do have to dig into the physiology of stress and discuss the whole process that leads to the stress response we commonly think of. To do this, we do kind of need to discuss things separately, which initially makes it a little harder to follow along, but I will tie it all back together in the end and discussing things this way will allow you to understand it a little bit better.

Stress and the Nervous System

The nervous system is actually an important part of the stress response, and understanding its role has a very direct impact on our stress management practices. You don’t need to be an expert on the nervous system to understand stress, but there are some key things you need to understand to really be able to craft effective stress management practices. The nervous system is especially important to understand, as a lot of the things we do for stress management actually work via the nervous system.

Most people just think of the nervous system as the “electrical wiring” of the body and are really only aware of it when something goes wrong with this wiring (i.e. you have some nervous system pain like sciatic nerve pain, or you have some sort of nerve related muscle weakness), the nervous system is actually a vital part of the stress response. The nervous system isn’t just the electrical system that allows you to coordinate movement, it is the system your body relies on to coordinate your response to any stimulus. It is the superhighway that transmits the signal of a stimulus (stressor) to the relevant command centres (your spine and/or your brain), and then transmits the response back.

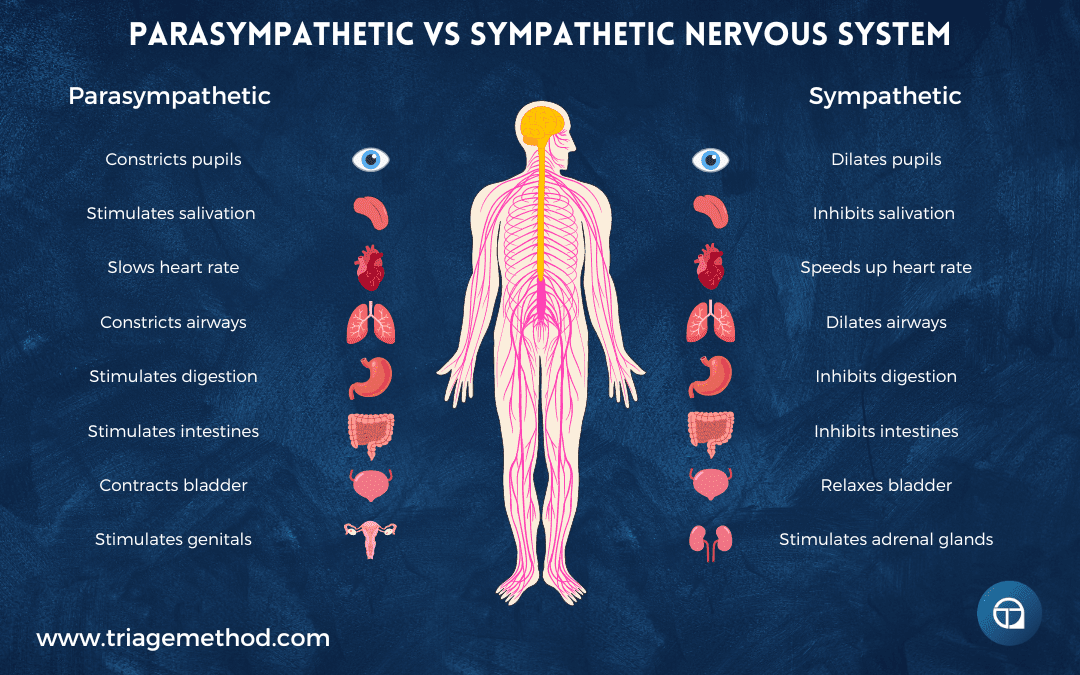

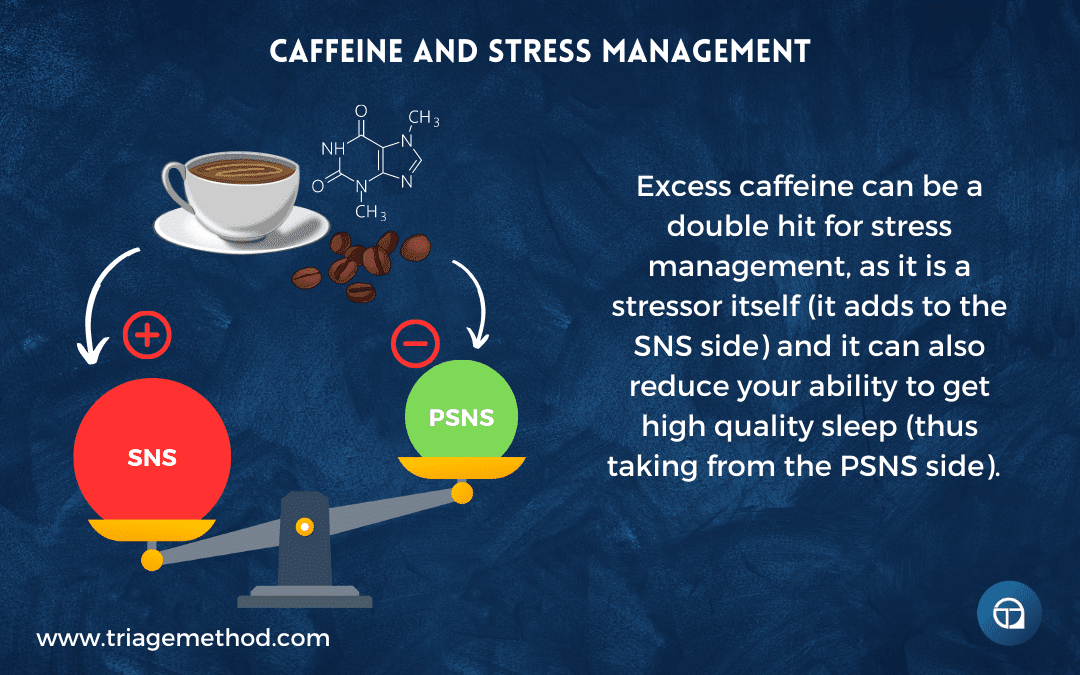

You have a central nervous system (basically your brain and spine) and a peripheral nervous system, which is further subdivided into the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. The somatic nervous system is less important for this discussion, as it is basically the nervous system branch that controls voluntary movements (which is still obviously important, as voluntary movement is still important to the stress response overall). What we are really concerned about in this discussion is the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS can be further subdivided into the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) and also the enteric nervous system (ENS). The ENS is less important for this discussion right now, but it does play a role in discussions around nutrition and stress.

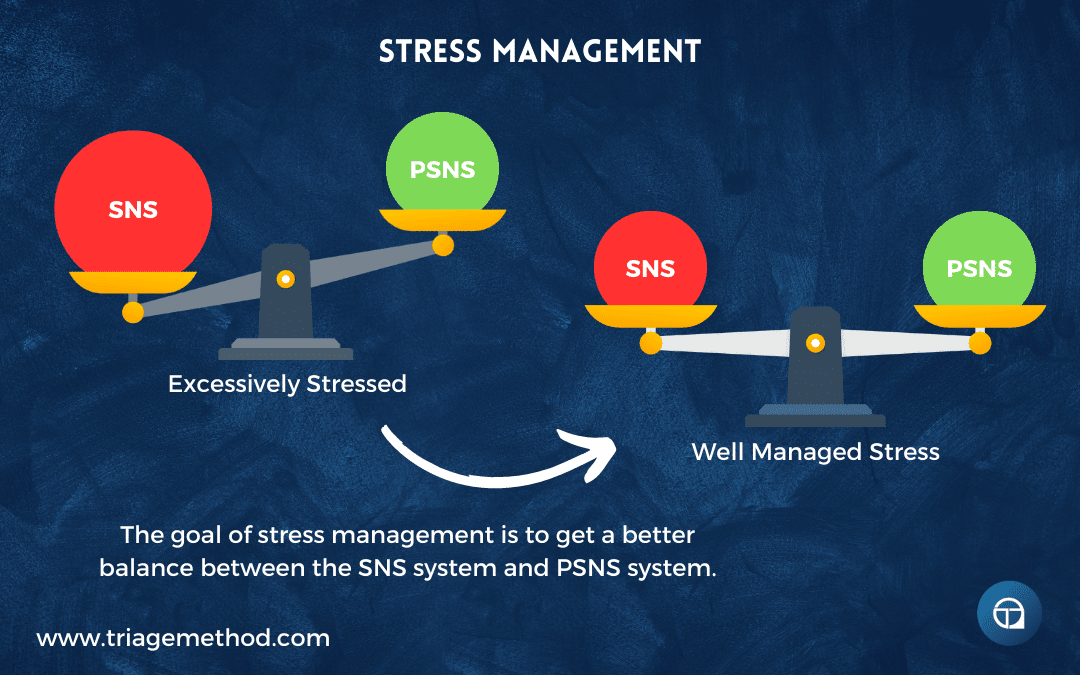

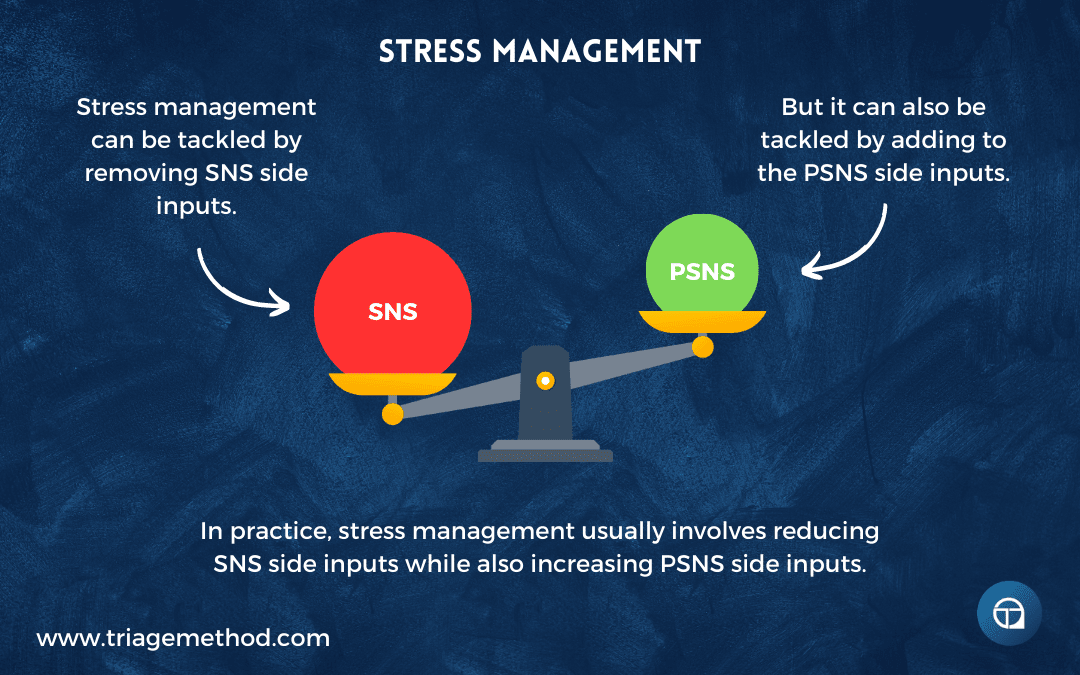

The whole system is more complex than this, but what I really want to emphasise is the fact that you have these various branches of the nervous system, notably the SNS and PSNS. Now, this is important to emphasise because it helps us understand stress more, and it has a direct impact on our stress management practices. You see, when most people discuss stress, they are really discussing SNS-related actions. The SNS is often referred to as the “fight or flight” system, and this does exactly what it says it does. It is the system responsible for ramping you up so you can either tackle an issue head-on (fight), or run away from it (flight). We must remember that this response is neither inherently good nor bad. It is the system that allows you to mobilise the stored fuel in your body so you can run away from a threat or tackle it, and it is also the system that leaves your palms sweating and your heart rate racing because you have to speak in front of a crowd. Same system, different stimulus, different perception of things. It should be noted, that women don’t always react in the same way that men do to a stimulus, and they often display a “tend and befriend” response, rather than a strictly “fight or flight” response to certain stressors. The “tend and befriend” response refers to the protection of offspring (tend) and the behaviour of seeking out a social group for mutual defence (befriend). This difference in response to stress may not be outwardly different in a noticeable way (i.e. a mother bear being incredibly aggressive to protect her cubs may not appear to be noticeably different to a male bear simply aggressively attacking), but it is important to realise that there are subtle differences and these are important for both our understanding of stress and our stress management practices as there may be differences in how men and women experience and deal with stress.

This whole process is more clearly illustrated if we actually walk you through the whole process of stress, from a nervous system perspective. In response to a stressor, a message is transmitted via the nervous system to the brain (hypothalamus/brain stem) and gets interpreted and relayed to the ANS. For this discussion right now, how it gets the message is less important, and what we really care about is the cascade of events that occurs at the nervous system level and after, once that message is received. A message is received and interpreted in the hypothalamus, which then sends a signal to the SNS, which then relays this signal to the many organs and systems in the body. The SNS innervates many target tissues, but one of the things it targets is the adrenal medulla. Once appropriate signalling is given via the SNS, the adrenal medulla releases adrenaline and noradrenaline, which serve to enhance the nervous system effects by binding to adrenergic receptors around the body. This is what precipitates the “fight or flight” response. As the SNS has multiple targets around the body, this is why you get such a wide variety of effects.

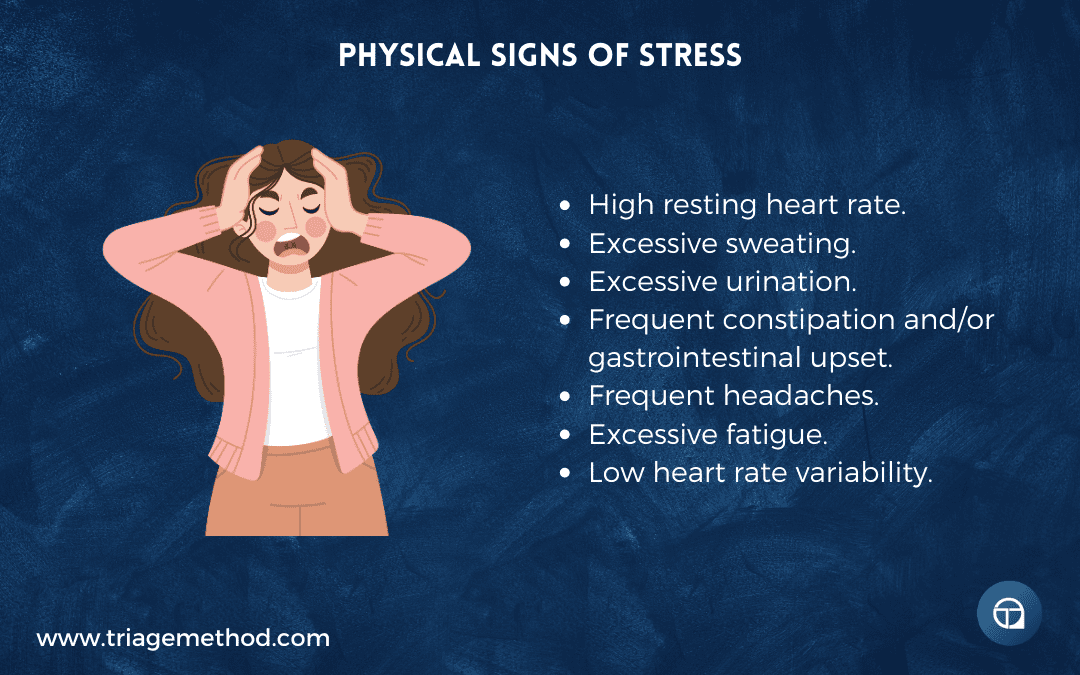

You see dilation of the pupils, increased heart rate and force of contraction, vasoconstriction, changes in blood pressure, bronchodilation (breathing becomes easier, although your actual breathing rate will likely increase when stressed, and most people end up taking short and shallow breaths too), sweating, a lot of metabolic effects that serve to make fuel more readily available and the metabolism less focused on “storage” (glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis), and then you see digestion changes (you see decreases in gastric motility (so you potentially struggle to poop) and then also relaxation of the bladder (so you urinate more often)), and as I mentioned above and will discuss further below, you get stimulation of the adrenal medulla. These effects make sense given the context of the SNS being a very fast response system that is supposed to help you to deal with a stressor. In nature, that stressor is likely to be a predator chasing you, or you chasing a prey animal, so it makes sense that you would want to get a signal to different parts of the body that make that easier. Your eyes widen, you are more focused and can see better, your heart rate increases, you can breathe better, and you feel amped up and ready to respond very quickly. However, we don’t live in nature these days, and thus there is a mismatch between what this system was developed for and the way we currently live, and that has some implications we will discuss throughout this article.

Now, before we go on further, we must circle back and remind ourselves that the PSNS is also part of this system. The PSNS is often referred to as the “rest and digest” or the “feed and breed” system, and it also does exactly what you would think it does based on that name. The PSNS is responsible for bringing the heart rate down, relaxation, and it also plays a significant role in digestion. If you have ever had a big meal and then fell asleep straight after it, that is a very good illustration of PSNS activity. However, as you can imagine, being in this relaxed state isn’t appropriate all the time, and this is why we can’t view things in a binary good or bad manner. It also plays a role in hormonal health, mating and procreation. While SNS activity can be thought of as the time for mobilising stored fuel, PSNS activity can be thought of as the time for building for the future. This naturally has implications for health, but for those of us trying to build muscle and improve our performance, spending time with high PSNS activity is vital. The PSNS also plays a pretty big role in mating and procreation, and this should be obvious enough, as most people don’t generally see their sex drive increase when they are highly stress (high SNS activity) and generally do see their sex drive increase when stress is low (high PSNS activity).

The PSNS basically innervates many of the same targets of the SNS, and for this discussion, effectively has the role of turning the dial the other way from the SNS. The pupils constrict, heart rate is reduced, blood pressure reduces, the lungs constrict (bronchoconstriction, as you don’t need to be gasping as much air in as possible when you are relaxing, and you also tend to see long, slow, deep breaths when the PSNS dominates), you get increased activity of the digestive system and you get a contraction of the bladder walls. So the PSNS basically turns the dial down from the actions of the SNS, and this is generally discussed in terms of returning to normal, often called homeostasis (which we will discuss later on). However, that is only the role of the PSNS after the SNS has been activated and it does have effects outside of this.

Stress and the HPGA Axis

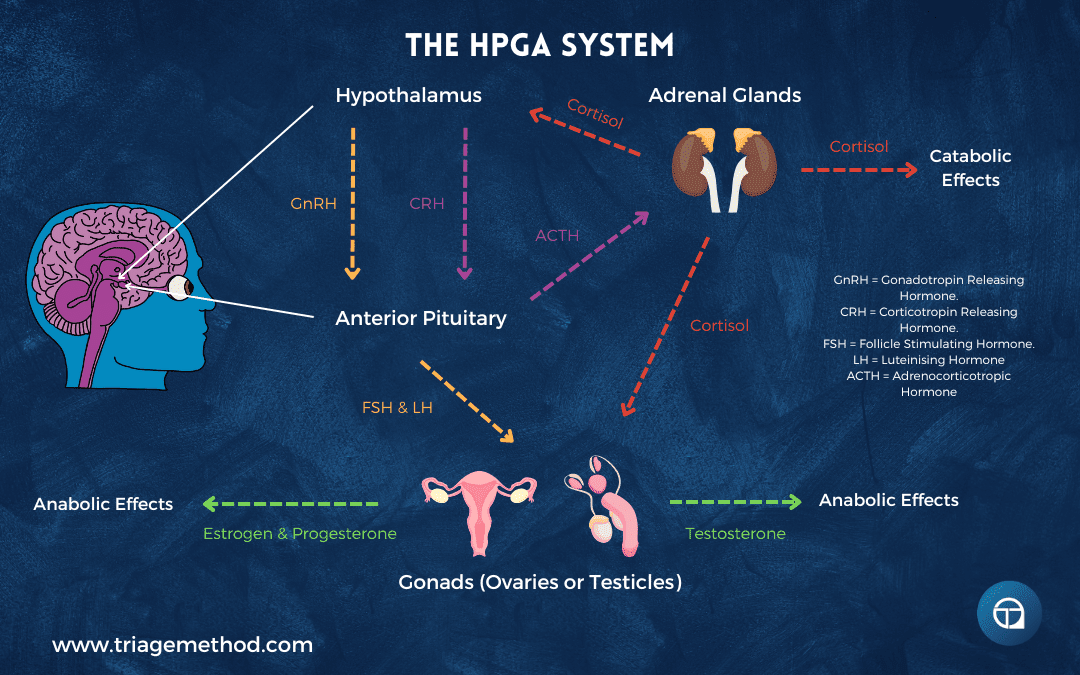

The stress response isn’t just a nervous system phenomenon, however. There is a hormonal element to stress too, and this does have implications for both our understanding of the effects of stress, what stress looks like and our stress management practices. You see, the nervous system is only one part of the stress response. While you do have to understand the nervous system component, you do also have to realise that there is a hormonal component too. The nervous system can be thought of as the “fast” system, and the hormonal system can be thought of as the “slow” system (the nervous system is basically electrical circuitry, whereas the hormonal system has to travel through the slower bloodstream to get to the target). There is a rather complex interplay of various hormones occurring in response to stress, but for this discussion of the stress response, you just need to understand that there is a hormonal component to stress. Stress affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal-adrenal (HPGA) axis, which can be thought of as the brain-to-hormone system, as it is the system that coordinates a variety of hormonal responses to inputs the brain receives.

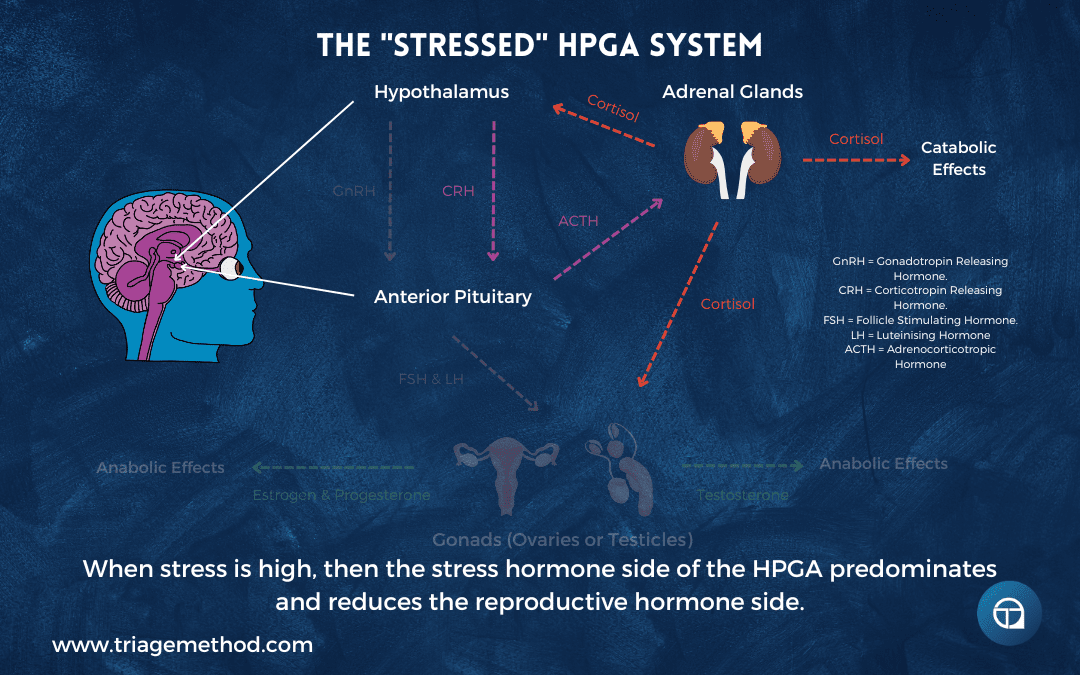

In response to a stressor, the hypothalamus receives and interprets the information, and then transmits it to the SNS to respond (as described in the last section). However, it also communicates with other areas of the brain (namely the pituitary glands), and other areas of the brain also communicate with it (such as the amygdala). The hypothalamus signals (via hormones) to the pituitary to secrete hormones that travel in the blood, which serve to then signal the adrenal glands to secrete what we classically think of as “stress hormones”, such as cortisol. These hormones serve to enhance the effects already being signalled by the SNS, while also serving to mobilise stored fuel (i.e. it mobilises fat and carbohydrate stores). These stress hormones are effectively antagonistic to growth signals, as it doesn’t make sense to build up muscle mass or fat reserves, if you need it right now. I often describe stress signalling as “go time” rather than “grow time” (technically, it should be “grow and/or repair time”, but that isn’t quite as catchy), and this is important to remember for everyone reading this who is trying to build significant amounts of muscle (as high stress is antagonistic to this). Cortisol and the other stress hormones secreted do also have a variety of effects around the body, which we will describe a little more clearly in the “Effects of Stress” section, however, what is important to understand is that cortisol does effectively turn the system off after itself (I often describe this as closing the door after itself). The fact that cortisol down-regulates HPGA signalling, does have implications for our health and our stress management practices.

The process is different if the stimulus encountered wasn’t one that activated the SNS, and rather activated the PSNS. Effectively, you would see signalling that would serve to calm things down, rather than ramp things up. This is both hormone and nervous system mediated, and while the exact mechanics of this aren’t important for this discussion right now, what is important is understanding that certain stimuli elicit an SNS or PSNS response and there are hormonal differences between these two. We will discuss this more later on, but needless to say, this has implications for our health and stress management practices.

Now, we only really touched on part of this system, as we didn’t mention the “gonadal” (testicles or ovaries) side of things. These do form part of the stress response, and they are affected by stress levels. We don’t need to get bogged down in the exact signalling here, as it doesn’t massively enhance your understanding. However, what is important to understand is that the hormones estrogen and testosterone are often thought of as “grow time” signals, and while they can be elevated in response to a transient stressor, they are very often depressed in response to a chronic stress response. However, this pathway is bidirectional and your baseline hormone status does influence your ability to handle a stressor. There are differences in the way men and women respond to stress as a result, but there are also differences in how an individual response to stress at different stages of their life (as hormone levels fluctuate).

Understanding Stress

So far, what we have been describing is the classical “basic” stress response, where you encounter a stimulus and then your nervous system responds and activates the SNS, which is further enforced by HPGA secreted hormones, and then it is brought back to baseline by the PSNS. However, this is not the full extent of what stress actually is. It is somewhat reminiscent of what people colloquially discuss as “stress”, but it clearly isn’t the full picture. To build that fuller picture, and thus actually understand our own stress and how to set up effective stress management practices, we have to discuss the type of stress, the intensity of that stress, and then the time course of that stress. Understanding these will help us to really understand stress, beyond just the basic stress response understanding (which is still important, as we need to understand that the nervous and HPGA systems are still heavily involved).

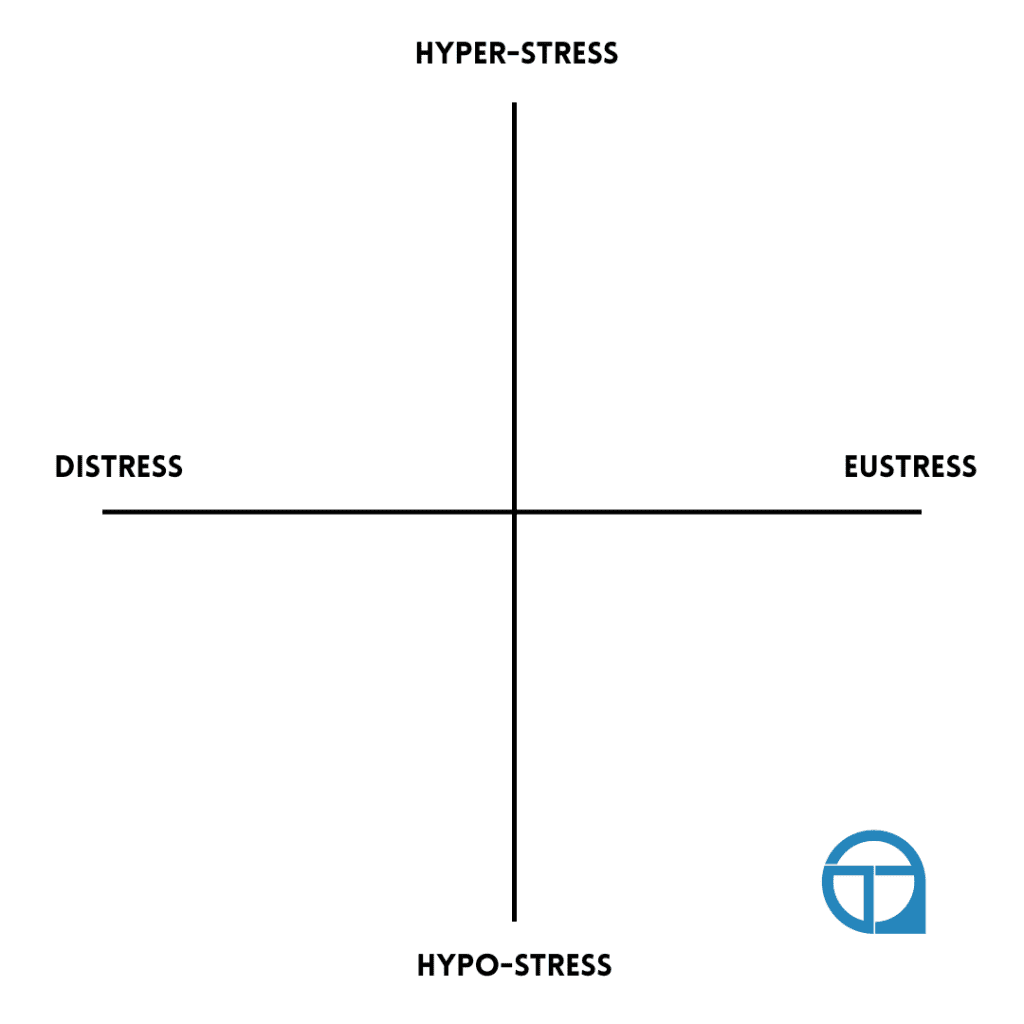

While I did just say that what we have been describing is the classic description of a stressor and a stress response, this is not actually true. What we have been describing is a particular type of stressor, and a particular type of stress response. This is the type of stress that people very often think of, but it is not the full spectrum of stress, and it fails to help us really understand stress in the modern world. What we have been describing is “distress”, and more specifically “hyper-stress” distress. You see, we can categorise stress into four varieties (and then we can add a time component to this), which are eustress, distress, hypo-stress and hyper-stress. Hans Selye (who basically invented all our current thinking about stress) proposed these four varieties of stress, and that they could effectively be mapped on two axes. On the X-axis, we have good stress (what he termed eustress) on the left and bad stress (distress) on the right. On the Y-axis, we have over-stress (hyper-stress) on the top and under-stress (hypo-stress) on the bottom. While this is a very simplified concept, it does help us at least visualise what is going on and can be used as a tool to orientate ourselves with what stress inputs we have going on.

Hyper-stress is fairly intuitive to understand, as most of you have likely gone through periods of being too stressed, and thus you know what this feels like. Hypo-stress on the other hand sounds like it isn’t a problem, and you may be asking: “how can you be under-stressed?” Well, you can be under-stressed, and this can be more clearly understood when you consider that a stressor is simply a stimulus. You have likely felt under-stimulated before, and while this may have just resulted in some boredom for you, imagine if you had to go through long periods of time where you were actually chronically under-stimulated. You would likely start engaging in behaviours that were more extreme, so you could get some sort of stimulation in your life (humans can regularly be seen destroying their entire life to get away from being under-stimulated, as evidenced by many celebrities). You see, when we discuss the balance between hypo- and hyper-stress, what we ideally want is to be somewhere on the actual X-axis line (the Y coordinate is 0). So hyper-stress and hypo-stress are balanced. We aren’t too stressed out and we aren’t too relaxed, as we do need stress to actually get stuff done and we do need stress to actually get better at and adapt to, well, life. There are obviously going to be periods of time where you are hyper-stressed, and you will have periods of time where you are hypo-stressed, but what we want to do is understand where we are with this stuff, so we can balance that stress over time (i.e. we aren’t always hyper-stressed). We will come back to this discussion of hypo- and hyper-stress a little bit later on, when we discuss the time component and adaptation to stress.

Now, the discussion of eustress and distress isn’t as intuitive as the discussion around hypo- and hyper-stress. Most people find it very intuitive to think of stress as being either too much or too little, and it accords very well with our general colloquial discussions around stress. However, most people don’t tend to think of stress as a good thing, and the discussion of stress focuses mainly on “distress” (“bad stress”). “Eustress” is a little bit harder to wrap your head around, and most people will immediately think of hypo-stress when thinking about this (i.e. they will think about states of hypo-stress, such as relaxing as the opposite of distress). You see, this is why I mentioned perception earlier when discussing stress, as two people may go through the same stress, but experience it totally differently. Eustress is the type of stress that you are exposed to, but you grow from it. This is very easy to understand when we consider resistance training, as the training session is a clear example of eustress. The training itself is a stressor, but by completing it, you gain a benefit and grow from it (assuming the training stimulus wasn’t too excessive). Similarly, as a child, you may have been incredibly excited about a specific event (such as a religious holiday or birthday celebration) and experienced many of the “symptoms” associated with distress (i.e. elevated heart rate, increased blood pressure, sweating etc.), but the stressor was actually a positive experience that you gained something from. Climbing a mountain may be difficult during the climb, but when you reach the top, or in the days afterwards, the stress is often viewed as an incredibly positive stress. So the event can both be perceived as challenging or enjoyable in the moment, but it can still end up being positive after the fact. However, eustress isn’t always actually positive, as you can still have “hyper-eustress”, and too much of a good thing is often a bad thing. For example, the child who is overly excited about an event and can’t sleep, eat or do the basic functions they should be able to do is experiencing too much of a good thing, which if let go on long enough, quickly turns to a negative. Similarly, while exercise can be eustress, too much of it can lead to negative outcomes.

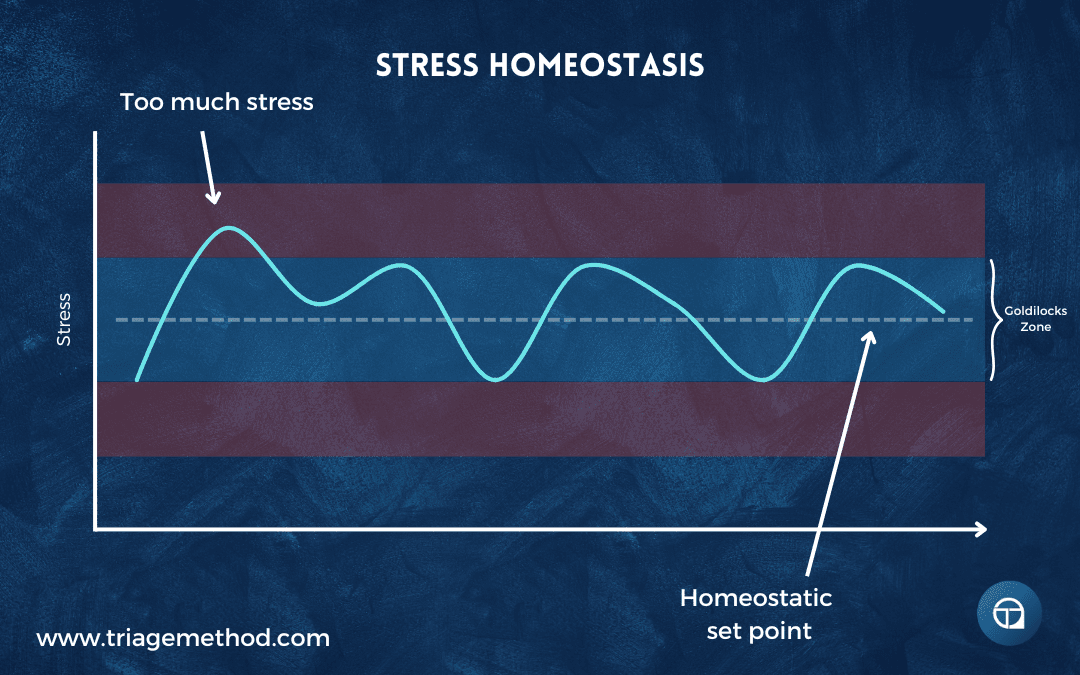

So we still can’t think of stress as being positive or negative, and it really is a messy discussion overall. What can be helpful to think of is simply that the body likes to be at a certain set point and it doesn’t like to deviate from that set point if it can. In biology, we often call this homeostasis, and your body will try to maintain a certain equilibrium, not swinging too far in one direction or the other, instead, it tries to stay around a certain point. The body tries to stay in this Goldilocks zone, and the various stressors you encounter in your life (whether you perceived them as good or bad, too much or too little) are trying to move you away from this Goldilocks zone. Your body is simply mounting a response to deal with the stressor, so you can then return to the Goldilocks zone. This Goldilocks zone way of thinking about stress is actually quite helpful, as it gives us a nice framework to better understand the stress response and what the goal of stress management practices actually are.

Now, you may have noticed when we were discussing both the nervous system and the hormonal response to stress, both of these things involved a specific area of the brain, the hypothalamus. Well, wouldn’t you know, it is the hypothalamus that is largely responsible for regulating your set point and maintaining homeostasis.

What people generally think of as stress is mainly “distress” and/or “hyper-stress”, and these serve to pull us away from homeostasis. We see high SNS activity, along with the HPGA system-mediated stress hormone secretion, and this serves to pull us away from the Goldilocks zone. This may be needed, so you can deal with an immediate stressor (i.e. you are dealing with a threat), but your body doesn’t like getting too far away from homeostasis, so once the threat has passed or been dealt with, the PSNS is activated and it serves to bring us back to “normal” (our homeostatic set point). At least, this is what is supposed to happen.

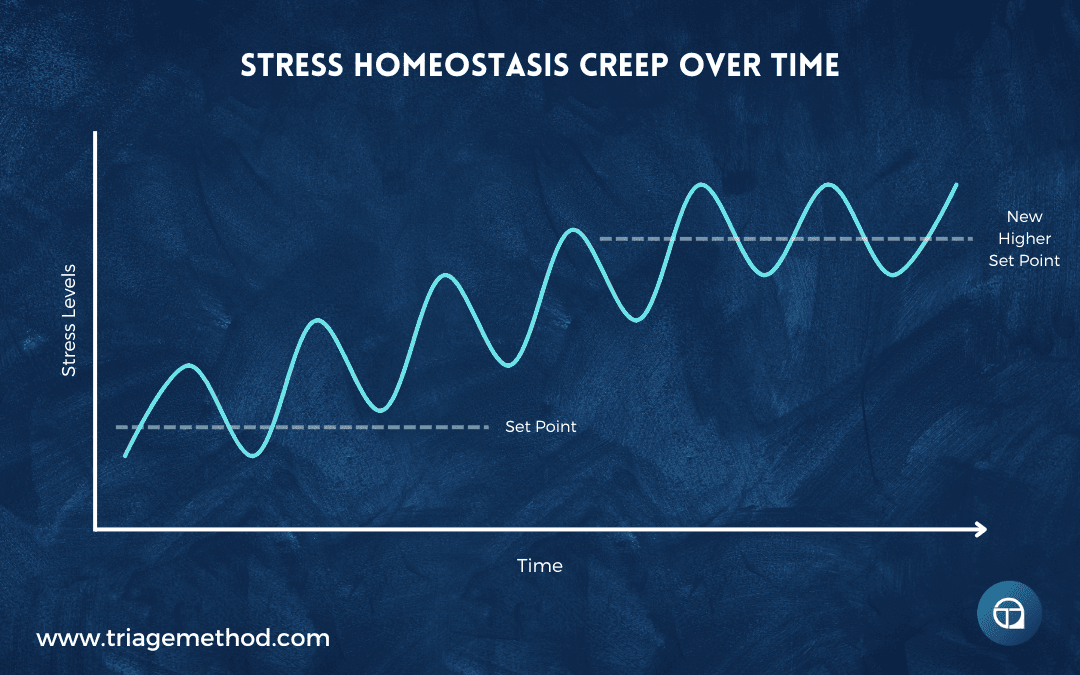

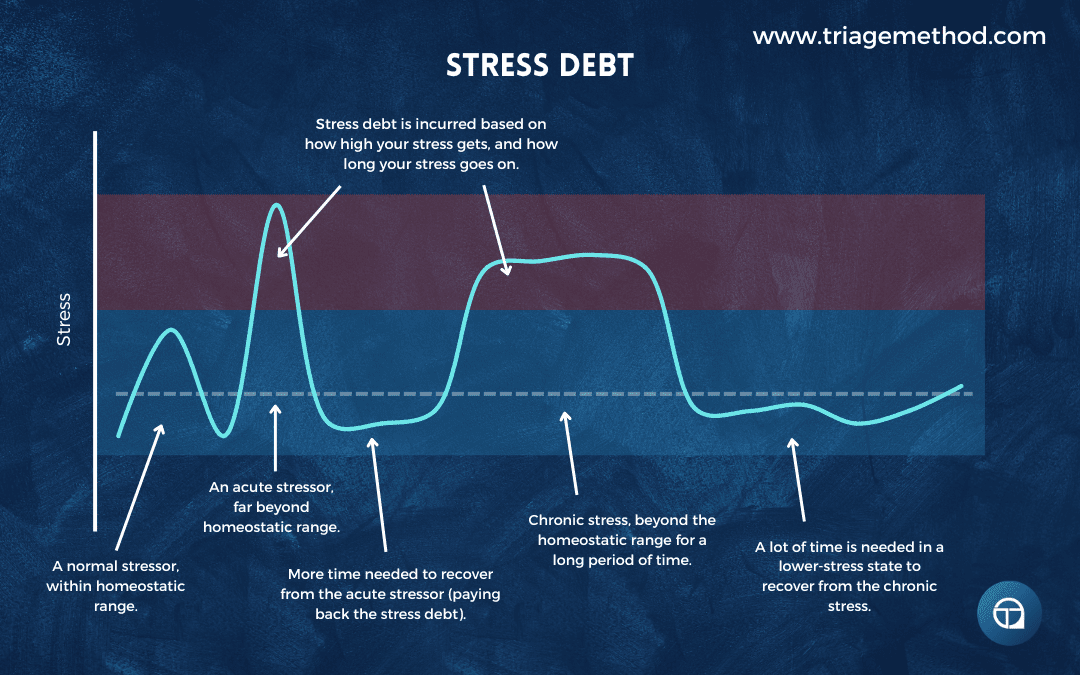

You see, it is important to realise at this stage that homeostasis is not a static point, and it does change over time. Your baseline set point will change depending on what you have been exposed to, and this is what allows you to actually adapt to the world around you. If it didn’t adapt over time, you would be left like a baby, where everything you experience is something that is a massive stressor trying to pull you away from homeostasis. You wouldn’t be able to adapt to stressors like training, and you would just be stuck exactly at that homeostatic set point. So the fact that we can adapt to stressors is good, however, it does potentially have a dark side. We will talk about the adaptation process more in a moment, but what is important right now is understanding that this system really isn’t well designed to handle chronic stressors. Spending a long time away from that homeostatic set point really only leads to two outcomes. You either become exhausted and your body forces you to take a break (i.e. you get injured, overtrained, have a nervous breakdown etc.), or you simply set your homeostatic set point further and further away from what is actually “normal”. We will discuss the first option in a moment when we talk about adaptation, but the second option is important to discuss right now, as it is very relevant to the discussion of the time aspect of stress.

This whole stress response system isn’t exactly well designed to handle chronic stress (at least from a lived experience perspective, although it is quite well designed from a “survival to reproductive age” perspective). Transient stressors can be more easily dealt with, even if they are quite intense. The more intense (or further away from the Goldilocks zone), the longer it may take to get back to baseline. In some very traumatic cases, it may be too intense and get you too far away from that Goldilocks zone and thus lead to longer-term issues, but in general, it is a fairly robust system. It is actually quite elegant in its design:

- Bear jumps out and growls,

- Your nervous system reacts causing you to respond (fight or flight),

- The HPGA system kicks in to support the response (fight or flight),

- You exhibit that classical stress response physiology that maximises your ability to respond,

- You escape,

- Your PSNS kicks in to bring you back to baseline,

- You go on with your life, hopefully having adapted and learned from that experience.

But this isn’t what we ask of the system now. In the modern world, the vast majority of stress in people’s lives is chronic stress. It isn’t just a single stressful event that you need to respond to and recover from, it is a constant bombardment of low to medium level stressors. These low to medium level stressors all serve to add to your overall stress, pulling you away from that homeostatic set point your body wants to be at. Prolonged stress can set then act to pull this homeostatic set point more towards a stressed position. So your homeostatic point is just a higher stress state to begin with, so even when you are at baseline, you are actually still dealing with stress.

It is like boiling water. Turn the heat up to full blast (transient, high intensity stress) and the water will very quickly heat and if you supply enough heat or let it go on long enough, the water will eventually boil over and we will have a mess to clean up. However, if you have this constant low level of heat (chronic, low-grade stress) boiling the water, you will eventually run out of enough resources to fuel the heating. Alternatively, if you have constantly been heating the water (chronic stress), it takes a much smaller blast of increased heat (transient stress) to have the water reach boiling point and start bubbling over.

So dealing with chronic stress can lead to a state where you are much closer to being overwhelmed by stress, and it can drag your homeostatic set point to having that be your “normal”. However, a lack of stress can drag your homeostatic set point away too. This is potentially why you see some people get very stressed out with very fundamental tasks which shouldn’t be stressful (their set point for stress is much lower, so even mild stress feels quite intense to them, although it could also be that they are already dealing with a lot of background stress and the fundamental task is just the straw that broke the camels back). It should also be noted that returning to “normal”, can also be a stressor in and of itself. Returning the body to homeostasis does still require resources, and while we think of the more PSNS activating stuff as generally enjoyable and potentially quite passive, there is still a physiological cost to the PSNS and of course, there is also potentially a mental cost barrier too. This is one reason many people are reluctant to stop being stressed, as to change actually feels like it is just an additional stressor for them. Finally, it should also be noted that your set point is influenced by your past experiences, and this unfortunately can just mean your set point is in a less beneficial place. This is especially true when we consider early life stress and trauma, and it may just take a lot of work and a lot of time to change that.

So, when discussing stress, we have to consider what type of stress we are talking about (eustress or distress), the magnitude of that stress (hypo-stress or hyper-stress) and the time course (transient or chronic stress). When most people discuss stress, what they really mean is some form of hyper-distress, and I will mainly be discussing things with this in mind going forward, but you now know that there is a lot more to this discussion. This may seem somewhat inconsequential, but it does all improve our understanding of stress, and more importantly for this article, it helps inform our stress management practices.

Stress and Adaptation

Now, you have a much better understanding of stress, and the final piece of the puzzle we need to discuss is the adaptation process. As we noted previously, your homeostatic set point is not static, it changes over time. One of the things about stress is that you do actually adapt to it, or at least you have the potential to adapt to it, if it isn’t too intense or if it doesn’t go on for too long. This adaptation process is important to understand as it is the basis for the fitness related stuff we do (i.e. getting stronger, getting fitter, building muscle etc. all require adaptations to occur) and it also is really important for our stress management practices. We don’t want to completely remove all stressors, we want to keep stress at a manageable level and coming from the right places, so we can actually adapt and become more resilient.

While we tend to have this notion when discussing stress that it is bad, however, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Yes, for sure, always being in the distress/hyper-stress position is far from optimal for our long-term health, but that doesn’t mean these things are bad. If you went for a walk in the woods and a grizzly bear jumped out from behind a tree and started chasing you, you would be extremely happy with your ability to get into this hyper-stressed/distressed position, as it would allow you to quickly respond to the threat and it would provide your body the resources needed to escape the threat. You would likely be pretty damn tired after running away and getting that dump of stress hormones and it likely would take you a few days to really get over it. However, it isn’t just in that singular moment that that stress is beneficial, you see, stress triggers adaptations. While an initial stressor can cause you to easily get into that hyper-stress/distress state, if this is your thousand time in that situation, the feelings of stress are likely to be very, very low. After all, a stressor is just an input of information, and the stress response is just your body trying to respond to that information appropriately. If you have done something a thousand times, and you know how to deal with it, it is unlikely that you are going to be extremely stressed out by it. You have adapted to that stressor, and it no longer disrupts your homeostasis significantly.

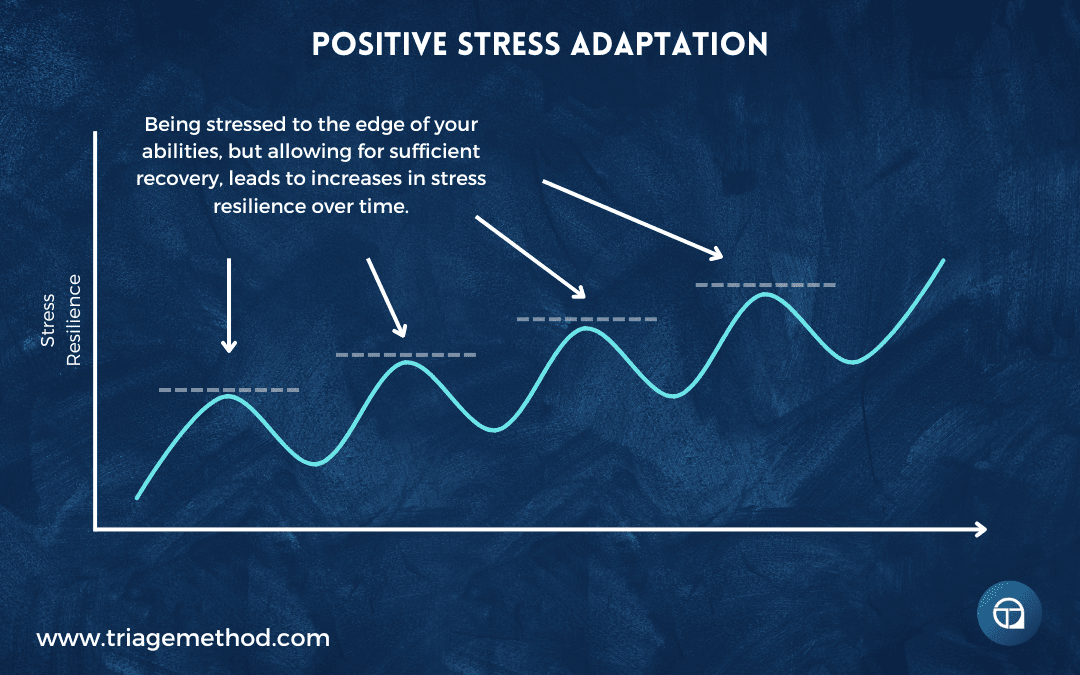

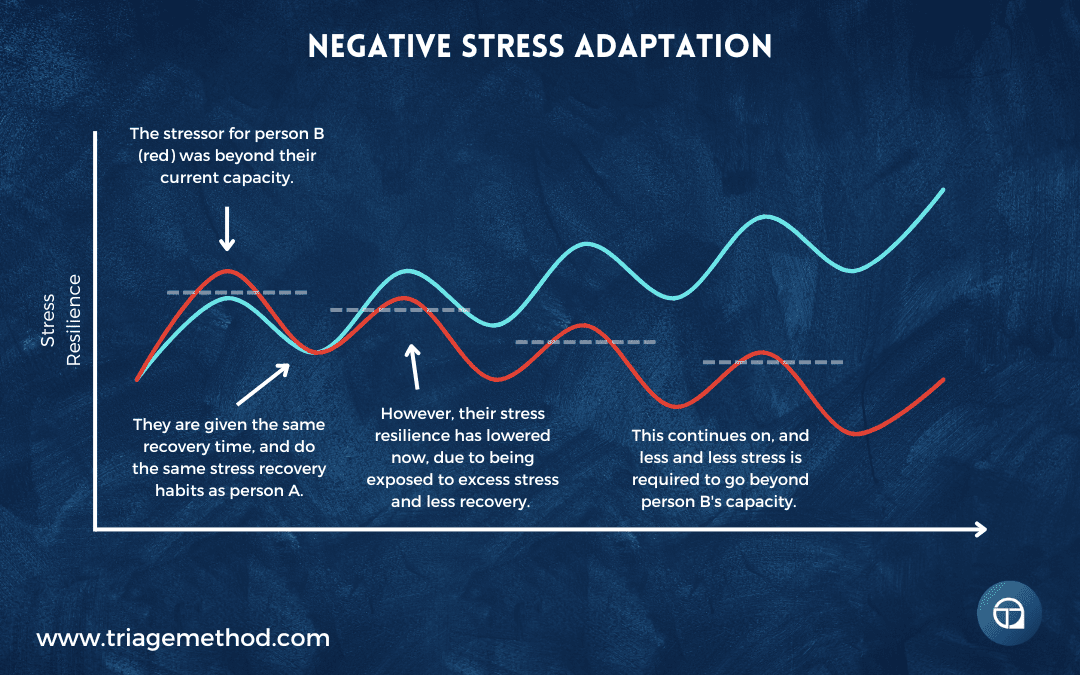

While there is some pretty cool physiology underpinning this stuff, we really only need a rudimentary understanding of the adaptation process for our needs here. When you are exposed to a stressor, your body responds to that stressor. If it is too intense, or goes on for too long, you will reach a point of exhaustion. However, if the stressor is at a manageable dose, your body will recover, and be more stress resilient in future. This is very clearly illustrated in the gym with resistance training. You lift a weight that is close to your current capacity, and once you are able to recover, the next time you go to lift that weight, it will be a little bit easier. You have adapted to the stressor, and you have become a little bit more stress-resilient over time. This is also a tool psychologists use to help people overcome issues they are experiencing in their lives, and they call it exposure therapy. For example, if you were afraid of spiders, you would slowly expose yourself to spiders. You wouldn’t just go from fear of spiders straight to holding a tarantula in your hand, and you may need to simply start the exposure process with something as simple as knowing there is a picture of a spider in the room. The process is graded, and it takes time for the adaptation process to take place.

Interestingly, you see the opposite process happening quite often, where people actually make themselves less resilient and less able to deal with stressors in their lives. Society seems to be moving towards shielding people away from stress, and this is a truly unscientific perspective of how to help people get better and deal with stress in the real world. Never being exposed to certain ideas or beliefs can leave people will an incredibly oversized stress response when confronted with those ideas/beliefs in the future. Living a life with no stress at all, generally leaves you far less stress resilient in future. This is very important to understand (hence why I have noted it a few times), as our goal with stress management is not to completely remove stress from our lives. The goal is to better manage our stressors so we can actually become more resilient and a better human over time.

Right now, the important thing to understand is that stress is required for adaptations to occur, but we just need to be aware of the magnitude of stress we experience and the duration of it too. While the body adapts to stressors, this can only occur if you can actually handle that stressor. If the stressor is too much, or goes on for too long, then you may not be able to handle that stress, and you may not be able to adapt and get more resilient. You have to balance the stress exposure with recovery time, and this is the key to stress management. We aren’t trying to remove all the stress from our life, we are trying to become more resilient. To do this, we have to understand what stressors we are being exposed to, manage them better so that they aren’t as intense and/or they don’t go on for as long, and we also need to ensure that we are actually sufficiently recovering. That is the goal of stress management.

However, it is important to also understand that stress tolerance and resilience is going to be different based on your life experiences and genetics. There are also differences in stress response based on both age and sex. Throughout our life, our capacity for stress changes. This is straightforward enough, as we notice the same ebbs and flows with most other physiological functions, with childhood being different from adulthood, and that being different than when we enter our golden years. However, stress is a slight bit different in that childhood stress (both during childhood and while we are in the womb) can have long-reaching effects on our overall physiology. This is important to understand, as everyone does have very different life experiences, and this can profoundly change our ability to handle stress. Of course, traumatic events can happen at any time throughout your life, and if you didn’t have the stress resilience already built to handle them, it can be a very tough climb to get back to a “normal” stress level. Our sex also impacts the whole stress system. This is actually quite complex, and does become very relevant when discussing certain topics (such as the immune system and stress). We won’t get into it now, but do realise that males and females respond to stress somewhat differently, and very often stress is only discussed from the male perspective (of course, there is still a large degree of difference even within each sex, but we can more broadly notice the general differences). While I am a male, and obviously can never actually feel what it feels like to experience stress as the “typical” female, I will where possible, also try to cover things from a female perspective (both from the physiological perspective and the more psychological perspective).

Effects of Stress

While we have covered quite a bit about stress already, what really helps to really understand stress is building out a better understanding of how stress affects the body. As we have discussed, when talking about stress, we are mainly talking about that “hyper-distress” type of stress. However, you must keep in mind that stress looks different to different people, depending on a variety of factors, and we can really only talk in generalities with this stuff, as people do react differently to different levels of stress. We must also remember that different populations (i.e. women vs men) do respond differently to stress, and this can really make all of this stuff difficult to neatly discuss.

I am going to break this section down into discussions on the health effects of stress, the effects of stress on nutrition, the effects of stress on training, and finally the effects of stress on sleep. However, there is a huge degree of overlap between everything that is going on with all of the things we discuss. There is also a large degree of bidirectionally with all of this stuff, where stress affects these different categories, but they also feedback into stress itself. This can be a little bit confusing, but it is something that works to our advantage, as we do actually have the ability to influence our stress by ensuring we do look after our health, nutrition, training, and sleep. Looking after our stress specifically will also further synergise with these and create a really nice positive feedforward loop.

The easiest way to understand how stress interacts with everything health and fitness, is to expand on how stress interacts with the HPGA system, and as a result, the many downstream effects. Understanding the basics of how stress affects the HPGA will allow you to more easily understand why certain issues may be occurring as a result of stress.

Note: I am going to state a variety of hormones in this discussion, and you simply don’t need to remember them all. Just try to understand the broad strokes with this stuff.

Stress and The HPGA

As you will recall, the hypothalamus is a part of the HPGA system, which also involves the pituitary, the gonads, and the adrenals. As a result, stress plays a role in the hormones secreted by the various organs in this system.

The pituitary is responsible for growth hormone secretion, along with hormones that are responsible for the facilitating the secretion of the sex hormones (luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)), it also plays a role in regulating the secretion of metabolism related hormones (thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which stimulates thyroid production). The pituitary also secretes prolactin, and adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH, which stimulates the adrenals to produce stress hormones).

The gonads refers to the testis or the ovaries, depending on the sex of the individual, and these are responsible for the main sex hormones testosterone and estrogen.

Finally, the adrenals are responsible for the secretion of many of the stress hormones, such as cortisol, aldosterone, adrenaline, and noradrenaline. They also play a role in the secretion of sex hormones such as DHEA (which is a major “male” sex hormone for women, and can also be converted to testosterone or estrogen).

Now, I realise I have just stated a load of names there, and I haven’t really told you how stress affects things, but this is purely just to establish the fact that the whole system is very interlinked, and you aren’t just creating stress hormones in isolation. In fact, all of the hormones are interacting in complex ways, and there are multiple points of feedback between the hormones along the way.

The best way to more clearly illustrate things is to simply do a walk through of what happens in response to stress. Let’s imagine you get exposed to a stressor. If the stressor is mild, then you may get very small hormonal changes in the short term (although you may get them in the long term especially if the mild stressors are frequent). You will see an increase in the catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), and perhaps a small bit of cortisol is secreted if the mild stressor is sufficiently stressful for you. So a very mild disturbance in the overall hormonal environment.

However, if the stressor is more intense or goes on for long enough, you get much larger changes. You get an increase in catecholamines with a larger/longer stressor, but a much larger amount of catecholamines are released. Now, this is what is giving you that “energy” to deal with the stressor, but it is also responsible for the stressed feeling (along with cortisol). So it is a double-edged sword. Further to this, these catecholamines are made from the precursor, dopamine. Dopamine is used for a lot of things, namely in reward circuitry in the brain, however, it is also part of the stress response. Your body uses dopamine release as a coping mechanism for stress, as it both makes you happier and it is part of the learning machinery in the brain. This allows you to feel less stressed, but also learn to handle the stressor better in future.

The catecholamines are largely responsible for that stressed feeling, although they are necessary and shouldn’t be viewed negatively. However, they do signal the start of a larger cascade of hormones in response to stress. Vasopressin along with corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) are released from the hypothalamus in response to stress. CRH then stimulates an increase in the secretion of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary. ACTH then acts on the adrenal cortex to increase the production of cortisol. Cortisol is what people tend to think of when they think of stress hormones, and it certainly could be viewed as a stress hormone. However, we must not fall victim to thinking of it negatively. With transient stress, cortisol is a healthy part of dealing with that stressor. It leads to the mobilisation of fuel to help deal with the stressor, acts as an anti-inflammatory, reduces inflammatory cytokines, and also acts as a negative feedback to CRH and ACTH, leading to a reduction in cortisol. All of this is fantastic for helping you deal with a stressor in the short term, and you can imagine that some of the cortisol effects would be particularly advantageous in the context of our evolutionary past. However, chronically elevated cortisol is much different and has detrimental health effects.

Prolactin is another hormone involved in stress, although most people do not associate it with stress, instead, linking it to pregnancy and breastfeeding (as it is also elevated during those situations too). However, prolactin release is stimulated by the rise in vasopressin I mentioned earlier. The exact reason for this is not fully understood, but it has been hypothesised that it serves as a way to get back to homeostasis. However, it should be noted that prolactin within normal ranges, can lead to an increase in testosterone which may be beneficial for dealing with stress. However, when elevated (especially chronically), prolactin serves to reduce the other sex hormones, testosterone and estrogen. It may also have effects on the immune system too.

Prolactin is one way in which the sex hormones testosterone and estrogen are affected by stress, but there are other mechanisms too. When under acute stress, there is a reduction of gonadotropins and steroid hormones. Under chronic stress, there is usually a quite severe reduction in sex hormones. This is because, sex hormone production is largely regulated by the HPGA axis, which is also heavily involved in the stress response. The hypothalamus is responsible for secreting gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), and the pituitary is responsible for producing luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in response to GnRH. LH and FSH are then involved in stimulating the production of testosterone and estrogen in the gonads (testicles or ovaries). However, when under stress, GnRH is decreased, most likely due to CRH.

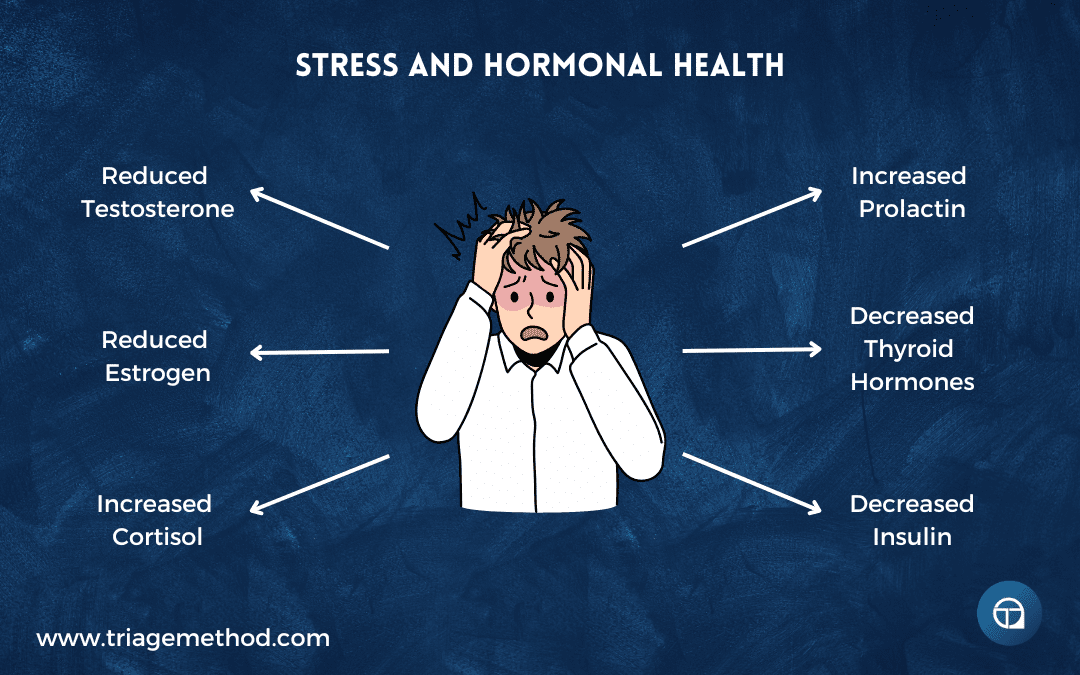

So in response to stress, especially chronic stress, the sex hormones decline. This has very important implications, both for health and fitness. Being in good health requires adequate hormone function, especially when we are discussing health topics related to reproduction and fertility. It is also incredibly relevant to fitness-related adaptations, as the sex steroids play particularly important roles (notably testosterone’s effects on muscle and strength building). The effect of stress on sex steroids also gives us a means by which we can gauge stress levels, as we can use things like libido, erection frequency, and menstrual function as proxy markers for stress. It isn’t perfect, but it does provide clues. Further to this, it is important to note that the hormonal system is never easy, and very often it is actually very complex. For example, reductions in testosterone lead to a reduced ability to handle stress. So we have a situation where chronic stress leads to reduced testosterone, which then leads to a reduced ability to handle the stress, further compounding the issue. This is the same in women, where menstrual function irregularities lead to less ability to handle stress and thus further dysfunction.

There are also some differences in the way men and women respond to stress, and this seems to be largely mediated by the sex hormones (both their transient effects and their long-term sex-differentiating effects). In response to psychological stress, cortisol sensitivity is increased, while in women the opposite effect is seen. Men also secrete more cortisol in response to psychological stress than women, producing more, even in anticipation of stress. However, in response to a toxin-induced cytokine increase (as may occur with infection or illness), the opposite effect is seen (and helps to explain why men “feel” sicker than women in response to illness, more on this in a moment when we discuss the immune system). Women see an increased sensitivity to cortisol, while men display the opposite. Estrogen also seems to blunt the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol, which may actually be an evolutionary advantage for the developing foetus during pregnancy, but it is also implicated in the increased risk of depression in women. There are many more little differences between the male and female responses to stress, and the various forms of stress, however, we simply can’t cover everything here, and it doesn’t change how we go about helping manage stress overall.

Thyroid hormones are decreased under stress. Stress inhibits thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which in turn, reduces T3 and T4 levels. This has very important implications for health, as thyroid hormones are vital to metabolism. It is also important to understand that stress decreases thyroid hormones (which in turn depresses metabolism), because a lot of people use very restrictive diets and high training volumes to induce fat loss, but both of these are quite stressful on the body, and may just serve to make fat loss harder by virtue of depressing metabolism.

Growth hormone levels are elevated in response to acute physical stress, and this may help with fuel mobilisation. Growth hormone has antagonistic effects on insulin, and thus it may serve to help mobilise stored fuel, which can then be used for energy in dealing with the physical stress. However, psychological stress rarely induces a growth hormone increase. In situations of chronic stress, growth hormone levels actually seem to be depressed. This makes you less able to deal with stress, and it also has numerous health implications, as growth hormone is necessary for good health. It also potentially has implications for those involved in fitness-related endeavours, as growth hormone is implicated in muscle building, and reductions in growth hormone are likely not what we would want in the context of muscle building.

Insulin is decreased during stress, and along with the fuel-mobilising effects of cortisol and growth hormone, can lead to elevated blood sugar in response to stress. However, it should also be noted that insulin is somewhat antagonistic to cortisol, and may help to explain why individuals who are stressed often times reach for sugary foods.

Ultimately, stress has a multitude of effects on the endocrine system, and while acute stress is rarely an issue (due to the effects being transient), chronic stress is almost universally bad for hormonal health. Unfortunately, modern stress patterns seem to be more aligned with chronic stress, rather than transited acute stress. We live in a chronically high-stress environment, and this has major implications for health in general.

Overall, large levels of stress are not beneficial for hormonal health, and this is likely to lead to a variety of negative outcomes, ranging from poorer fertility, poorer metabolic health, poorer response to training, poorer recovery and generally just suboptimal health in general.

Stress and The Nervous System

Now, while I have been heavily focusing on the hormones involved in mediating the effects of stress, we have to also remember that the nervous system is also involved in the stress response. The nervous system also innervates, well, the whole body, and while we mostly discuss the nervous system in regards to the more immediate effects of stress (i.e. its “fast” role in the response to a stressor), it does also have specific effects on various systems within the body. This can more easily be illustrated by quickly noting the targets of the SNS and its effects, and then noting how the PSNS tends to also target these systems and provide an opposite effect to the SNS-mediated one.

So you must bear in mind that it isn’t just the hormonal system that is causing effects in response to stress, and the nervous system “tone” is also mediating these effects by virtue of communicating directly to various organs that we are under stress. This is especially important to understand, because the nervous system tone is actually upstream of the hormonal stuff. So while the hormonal stuff (along with the nervous system) helps explain the effects stress has, the things we do to combat the negative health effects is actually stuff that mostly works on the nervous system side of things. Trying to work on all of the various effects of stress, or trying to target specific hormones is kind of missing the forest for the trees. Fixing the nervous system stuff should be the focus first and foremost, as that is the most upstream thing we can actually influence. Now, that doesn’t mean we ignore the downstream interventions or any focus on hormone “optimisation”, but it does mean that without addressing the nervous system, we will always feel like we are swimming against the current.

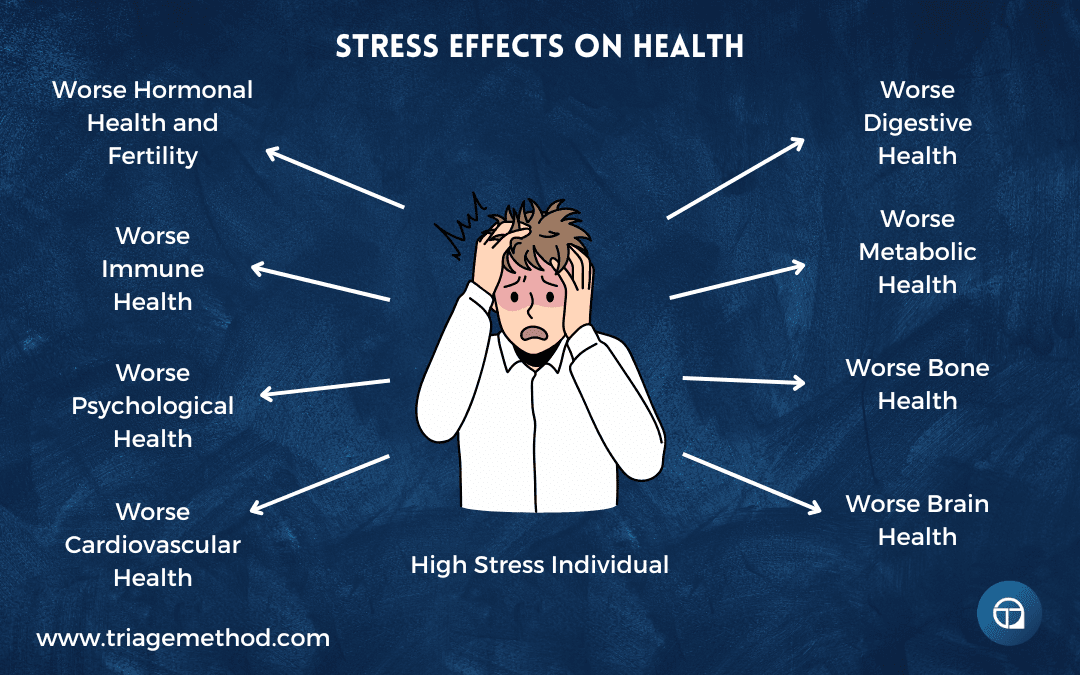

Stress and Health

Health is obviously a very broad term, and while we all kind of know what “health” broadly means, it is still a very large topic that is very interconnected. So, as a cop-out, I am just going to hit on the major points to be aware of, and rather than diving very deeply into the exact mechanisms for any one issue, I am going to provide an overview of the effects stress has on health. So far in this section, you have built a better picture of the why behind the effects of stress (hormones and the nervous system), and now we can actually look at the specific effects stress has on your health.

While I did already discuss it quite a bit a moment ago, I just want to reiterate that stress negatively affects hormonal health. Notably, the main sex hormones, testosterone and estrogen. This can result in a host of health issues, as good hormonal health is vital for the proper functioning of the body. Of particular note is that this generally manifests itself in fertility and/or libido issues. Many of the things that are often recommended for improving fertility and/or libido are actually directed at managing stress more effectively. However, it should be noted that not all libido or fertility issues are stress related.

Stress negatively affects the immune system. Cortisol has immunosuppressive effects, as cortisol has anti-inflammatory effects and serves to reduce the expression of inflammatory cytokines (which the immune system needs to fight infection) and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines. At least in acute stress, this is what you see. However, in chronic stress, we see reduced immunosuppressive activity. You may think this is a positive, as surely you want your immune system fully functioning, don’t you? Well, you see the issue is you don’t want your immune system constantly on high alert. You want it to get the job done, and then relax. In chronic stress, it is always on high alert, and there isn’t the relaxation we want. Acute stress seems to also enhance the immune response, despite it being somewhat immunosuppressive. However, chronic stress suppresses the immune system, and actually creates low-grade chronic inflammation, which in turn, may make you more susceptible to disease and even cancer.

The immune system is influenced by other hormones too (notably testosterone and estrogen), and as a result, there are differences between men and women with regards to the immune system. These differences may help to explain why women are generally not as impacted by something like the flu, whereas men get “man flu”. This is often played off as the man just being lazy or weak, but it is likely more representative of the differences in the immune system function. However, men tend to have an immune response that is more like the nuclear option, whereas women have an immune system that is more like a large standing army. The nuclear option immune system leaves the man absolutely wiped out in response to illness, whereas the standing army option immune system means women are better able to handle illness, but they are at an increased likelihood to develop many autoimmune conditions (if the standing army isn’t dealing with an outside threat, they start looking at stuff within the body as if it is a threat). Regardless of sex, high levels of stress (especially chronically) make your immune system weaker and thus make you more susceptible to disease.

A weakened immune system due to stress is naturally going to lead you to have poorer health in general. You may pick up more seasonal illnesses, and you may notice you take longer to recover from illnesses than other people (or indeed compared to yourself when you previously weren’t sick). I often think of the immune system as our “health force field”, and when you are under lots of stress, this force field is just weaker and thus a poorer defence against insults to your health. Less stress means a stronger force field, and thus a better defence against insults to your health.

Chronic stress negatively impacts cardiovascular health. It leads to higher blood pressure, it can negatively impact blood lipids, it can increase inflammation related to heart disease, and it also negatively impacts on the functioning of the heart itself, all of which make it more likely that you will experience a stroke and/or heart attack.

High levels of stress negatively affect the digestive system. This is largely due to the direct effects of the SNS on digestive function. Remember, the SNS is called the “fight or flight” system, whereas the PSNS is called the “rest and digest” system, and when the SNS system is dominant, digestive function is generally reduced. This can result in specific medical issues such as ulcers, but it can also result in more “every day” digestive issues such as constipation and/or bloating.

Stress negatively affects metabolic health, leading to worse blood sugar control and blood lipids. Chronic stress also negatively impacts on body composition, both leading to a reduced ability to gain/maintain muscle and a reduced ability to lose body fat, while also predisposing you to add more body fat. This increase body fat accumulation plays a role in reducing your overall metabolic health further, while also increasing inflammation in the body. The decreased ability to build/maintain muscle also increases your risk of death as you age.

Chronic stress also impacts on bone health, and chronic stress can lead to bone loss over time. This may not seem like a big deal, but when you consider that most people lay down their bone mass during their earlier years, and then reduce their exercise throughout their life, if we layer on chronic stress, we have a situation where bone mineral loss is accelerated. This can obviously lead to issues in the shorter term, such as fractures (which is actually quite relevant to athletes under high amounts of stress, from life, their training and/or from nutritional inadequacy), but it also leads to long-term issues such as osteoporosis in later years. As a result, you are more likely to sustain more substantial injuries from a fall in later years, which may lead to an early death.

The brain is also negatively affected by stress. Excess stress can lead to the shrinking of important brain regions, which can lead to reduced resilience to future stressors, reduced executive and cognitive functioning, psychiatric issues and psychological issues. Chronic stress can result in anxiety, depression and many other issues. Mood disturbances in chronically stressed individuals are extremely common, and they are one of the tell-tale signs of excess stress. This is all particularly relevant to individuals who were exposed to chronic stress in their youth, as they may not have developed their brains correctly as a result, and they may be more predisposed to a variety of mental health-related issues later in life.

There are a whole host of other potential health effects of stress, and we will touch on a few more throughout this article, but you can see that stress negatively affects health in a variety of ways. It should be remembered that these processes generally work both ways, and poorer health can lead to higher levels of stress or a reduced capacity to handle stress, which can lead to further health effects. Improving your health in a broad sense can help with the negative effects of stress on health (as you are better able to handle the stress), and improving your stress levels will generally result in better health all round.

Stress Diseases

Now, before we move on, I want to just briefly touch on specific diseases that may result from too much stress and diseases that may result in too much stress.

There are a number of disease states that result from too much stress, and while this is beyond the scope of this article, I think it does make sense to at least be aware that specific disease states can be caused by too much stress. The following are some disease states that can result from too much stress:

- Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common anxiety disorder characterised by uncontrollable worrying. Some people worry about bad things happening to them or their loved ones, and at other times they may not be able to identify any source of worry.

- Panic disorder is a condition that causes panic attacks. These are best described as moments of extreme fear accompanied by an elevated and “pounding” heart, shortness of breath, a fear of impending doom and often a feeling of the world “closing in”.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition that causes flashbacks or anxiety as the result of a traumatic experience. This is often talked about in regard to military personnel, however, it can happen to anyone who undergoes a stressor that is too much for them to adapt to or deal with at that time. This can occur with something that you personally would not consider a traumatic experience, however, we must remember that we all have different capacities for handling stress.

- Social phobia is a condition that causes intense feelings of anxiety in situations that involve interacting with others. This can be from low level all the way to high level, and this can be a significant barrier to people engaging in other health-promoting habits (such as going for a walk or going to the gym).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a condition that causes repetitive thoughts and the compulsion to complete certain ritual actions for fear that something bad will happen if the rituals are not performed.

There are also a number of diseases that can result in too much (or too little stress). Addison’s disease is a frequently cited one. In Addison’s disease, the adrenal glands cease to function, leading to an adrenal hormone deficiency. Cushing’s syndrome is a disease that results in the excessive production of cortisol, and all the ill health effects that go along with excessive exposure to high levels of cortisol. However, I won’t spend too much time discussing these, as they are stuff that a doctor will generally be required to help you deal with, and while stress management practices may help with these, I would prefer you actually seek help from a professional trained to help with these issues specifically, rather than just following the generalised stress management advice in this article!

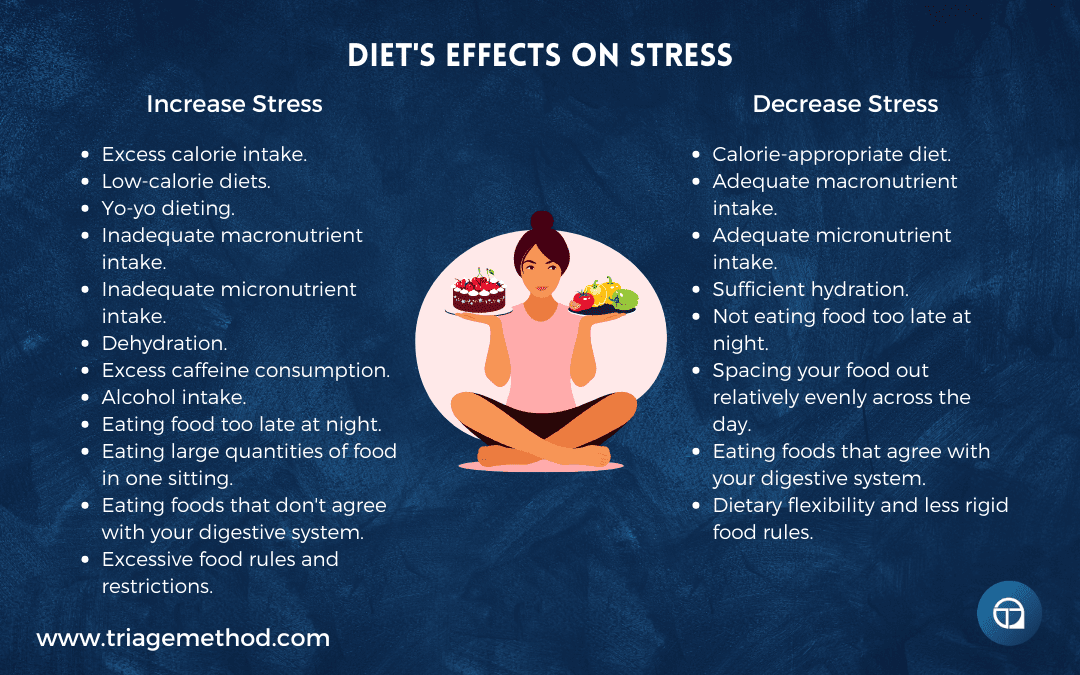

Stress and Nutrition

As this article is part of the foundations series, and naturally, the foundational stuff is the stuff that is, well, foundational to everything else, it makes sense that we expand on how stress affects the other foundational stuff (nutrition, training and sleep). So, let’s start with nutrition. Our nutrition is heavily impacted by stress, both in how we interact with the diet on a psychological level, and how our body responds to the food we eat. However, we should also remember that there is a bi-directional pathway here, and nutrition also effects stress and can be a stressor itself.

The diet can be a stressor, and stress can impact the diet itself, both in terms of quality and quantity. However, it is also important to remember that the nervous system is just responding to the stimuli it is presented with, and perception can alter this. So while I will be speaking in generalities, these should not be taken as a hard and fast rule. For example, fasting may be a negative stressor (inducing distress) for one individual, but for another who is doing some form of fasting for religious and cultural reasons may view that as a way to connect with their god and as such, it is a eustress for them. It is also important to remember that there is no zero exposure group here, as eating food can be a stressor and eating no food can be a stressor, and we all have some degree of stress impacting on our physiology and our nutrition practices in some form or another. However, despite this, we can still learn quite a lot from this discussion by speaking in generalities here.

When stress is higher (SNS activity), we see an increase in catecholamines and glucocorticoids. This “fight or flight” mode is counterbalanced with the “rest and digest” action of the PSNS. This should give you your first indication of the link between nutrition and stress. The high-stress environment is one where the focus is on mobilising energy to deal with the stressor, this inherently means there is a reduced focus on digesting and absorbing nutrients that have just been consumed. When stress is higher, digestion is worse and the processes of actually utilising that consumed food for anabolic purposes are reduced. Why would you spend energy building new structures or repairing old ones, when you are dealing with a stressor that might end your life? This would be akin to the city being besieged by invaders, and rather than picking up weapons to help defend the city, instead, you go about your same daily tasks as if nothing is going on. The body is a survival machine, and as such, if stress is high, resources are going to preferentially go towards dealing with that stressor. As a result, you get worse “results” (health, performance and body composition) from the diet.

It would make intuitive sense that because higher stress leads to a situation where fuel is being mobilised more readily, surely that would make fat loss easier? Well, unfortunately not. For sure, dieting to lose weight is a stressor (more on this in a moment) and we need that mild stress to help with fat loss, but when stress is excessively high (transiently or chronically) there is too much of a catabolic signal and we start to see more muscle loss along with fat loss. In most cases, we are looking to preserve as much muscle mass as possible while dieting, and if stress is high we, unfortunately, see excessive muscle loss. But further to this, stress leads to a situation where you are less likely to stick to the diet you have set up. This is because those same hormones that are used to mobilise energy, also tend to lead to the body feeling like it needs to replete the energy that has just been mobilised. This is especially true of glucose, as the glucocorticoids that allow you to respond to the stress, also lead to the partial depletion of the glucose in the blood, and this can lead to all that goes along with dips in blood sugar. In general, this leads to increased cravings for high carbohydrate, sugary foods. Glucose dysregulation is very often seen in high-stress individuals, both as a result of the stress itself (as it mobilises stored glucose) and because of the dietary patterns of high-stress individuals. Those glucocorticoids also interact with mineralocorticoid receptors and as a result, stress can also cause cravings for salty foods. Combined with this, stress can make you hold more water weight. As a result, high-stress individuals trying to diet start potentially seeing more muscle loss, the scales aren’t moving like they expect them to because of the water weight, and they are having stronger and stronger cravings for salty and high-carb foods. This is not a recipe for a successful fat loss phase, and it clearly isn’t health-promoting.

However, it isn’t just fat loss focused dieters that run into issues when stress is high. Even in a gaining phase (surplus calories), stress can cause issues. It should obviously be apparent that having a reduced ability to build muscle is less than ideal when trying to gain muscle, but unfortunately, high stress can make fat gain easier. This is also a particularly harmful type of fat gain, as it is generally in the form of visceral fat, fat stored around the organs. This type of fat leads to multiple negative health outcomes, and it further exacerbates the issues related to having high stress in the first place, as it puts further stress on the body. High-stress levels can also negatively affect digestion (because you never actually get into that rest and digest state), and as such, this can make getting the food required to effectively gain quality muscle size harder. Hunger can be reduced, and due to stress-causing reduced gastric motility, it can feel like food is just sitting in the digestive tract. Which naturally enough, doesn’t make you feel great, and can lead to reduced adherence and enjoyment of the diet.

Unfortunately, there is more. As I stated earlier, the actual diet itself can contribute to stress. Dealing with stress requires resources, and if you aren’t providing them from the diet, you will become less resilient to stress over time, as those resources are depleted. This is both in the form of the energy derived from the diet, the actual macronutrient constituents of the diet, but also the micronutrients obtained from the diet. When under stress, your body may have higher demands for certain nutrients, potentially above the normally recommended daily allowances. Eating a lower nutrient-density diet can also cause stress to the body, and if this is then combined with an increased requirement for certain nutrients due to an external stressor, then the body’s capacity to deal with stress will be further diminished. Low nutrient diets can be a cause of stress themselves, but they also lead to reduced resilience to stress from external sources. Eating a high-quality diet is vitally important to actually being able to deal with stress, unfortunately, the general population consumes a low-quality diet, and they are generally under chronic stress. This leads to a vicious cycle of reduced resilience to stress, and a higher likelihood that poorer food choices will be made, exacerbating the issue further.