Now, you may be thinking, what the hell are quixotic ideals?

But if you’ve been coaching for a while, you’ve almost certainly experienced them. You have probably seen the client who arrives armed with the “perfect” plan. They’ve got a six-day training split they found online, a strict meal plan that cuts out everything fun, and a firm belief that this time they’ll finally get it right.

On the surface, that determination looks admirable. But underneath, it’s often driven by what I call quixotic ideals. They’re chasing a version of perfection in fitness and nutrition that doesn’t actually exist.

These ideals sound like discipline, but they usually show up as perfectionism and rigid “should” statements: I should be able to train every day. I should eat clean 100% of the time. I should already look like that influencer.

It’s not your client’s fault they think this way. The fitness culture around them is constantly feeding the narrative. Social media glamorises extreme physiques and transformations while hiding the messy context behind the images. Culturally, we glorify leanness, hustle, and sacrifice as if those were the only markers of health. Comparison is baked into human nature, and the industry itself often sells perfection as the product. Even highly educated, motivated clients fall into the trap, not because they lack knowledge, but because emotionally, these ideals promise quick certainty, approval, and results.

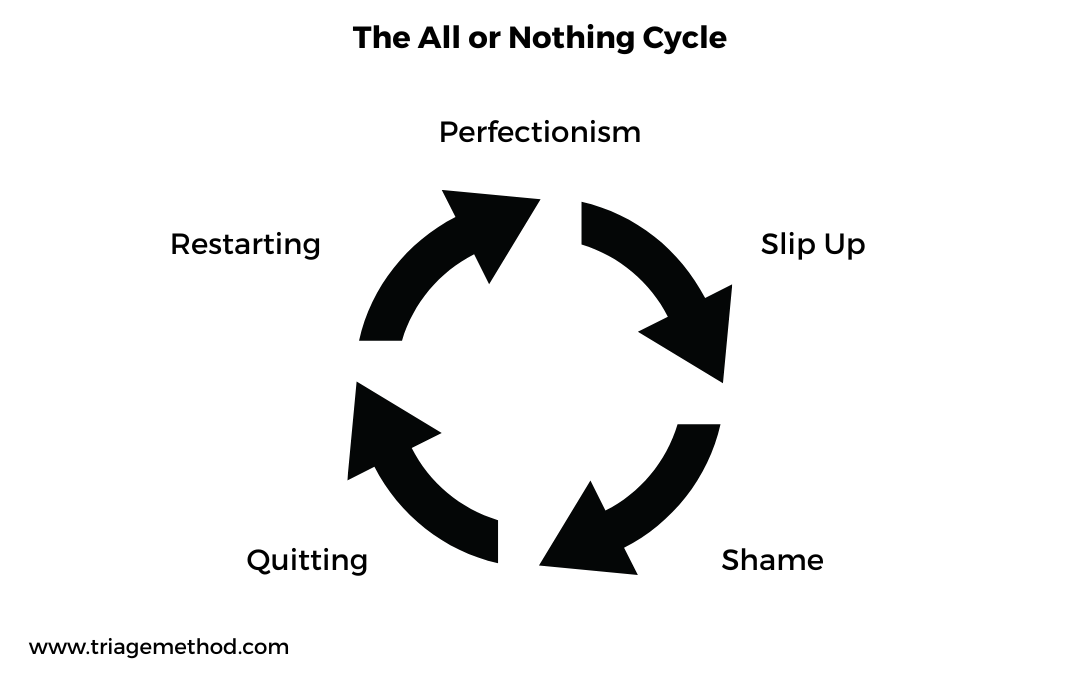

The trouble is that chasing these ideals almost always comes with a cost. Clients who buy into perfection end up frustrated when they inevitably fall short. They feel guilt when they “mess up,” as if it were a moral failure instead of a completely normal human moment. They burn out trying to maintain impossible standards, and because rigid plans don’t bend with real life, they fall into cycles of all-or-nothing inconsistency. Eventually, many quit, and not because they can’t succeed, but because the version of success they were aiming at was never sustainable in the first place.

This is where you, as the coach, matter most. Writing workouts and nutrition plans is the easy part. The real art of coaching is helping clients navigate mindset and lifestyle in a way that is sustainable and compassionate. It means learning to recognise perfectionist patterns, guiding people away from “optimal” toward realistic and doable, and helping them reframe “shoulds” into choices that give them a sense of agency. It means teaching flexibility, modelling self-compassion, and showing clients that progress and not perfection is what actually builds long-term change.

TL;DR

Quixotic ideals in fitness, perfectionism, “should” statements, and chasing the “perfect” plan, all set clients up for frustration, guilt, and burnout. They’re fueled by social media, cultural ideals, and industry messaging, but they’re not sustainable or real.

As a coach, your job isn’t just writing programs, it’s helping clients dismantle these ideals. That means:

- Spotting red flags in language and behaviour (“should,” all-or-nothing crashes, performative success).

- Reframing perfectionism into realistic, flexible, and sustainable goals.

- Teaching self-compassion, curiosity, and resilience instead of guilt and shame.

- Using tools like minimum effective dose goals, floor-and-ceiling planning, and reflection prompts to keep clients consistent in real life.

- Knowing when perfectionism crosses into clinical territory and compassionately referring out.

- Recognising and dismantling your own quixotic ideals as a coach so you can model imperfection and sustainability.

The goal isn’t a flawless plan, it’s helping clients (and yourself) build a lifestyle that adapts to real human life. Progress beats perfection.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 Understanding the Psychology of Quixotic Ideals

- 3 Spotting Quixotic Ideals in Clients

- 4 Coaching Strategies to Address Perfectionism

- 5 Practical Tools and Exercises

- 6 Real-World Coaching Scenarios

- 7 Boundaries and Red Flags

- 8 Meta-Coaching: Helping Coaches Break Their Own Quixotic Ideals

- 9 Conclusion: Coaching Beyond Perfection

- 10 Author

Understanding the Psychology of Quixotic Ideals

The word quixotic comes from Cervantes’ famous character Don Quixote. Quixote is a man so swept up in his fantasies that he mistook windmills for dragons and charged at them with his lance. His intentions were noble, but his targets weren’t real.

In coaching, we see the same thing all the time: clients tilting at their own “dragons” in the form of flawless diets, perfect training splits, or an idealised version of themselves. The problem is that these dragons don’t exist. The battle isn’t just unwinnable, it’s imaginary. That’s the danger of quixotic ideals.

Perfectionism sits at the heart of this mindset. Some clients carry what psychologists call self-oriented perfectionism. They have an internal pressure to meet impossibly high standards they’ve set for themselves. Others lean toward socially prescribed perfectionism. They have the belief that others expect them to be perfect, whether it’s peers, family, or the faceless judgment of “people on the internet.”

In practice, both forms show up as the same language patterns: endless shoulds. “I should be stronger by now.” “I should never miss a workout.” “I should be able to stick to this plan.” These aren’t harmless phrases, they’re cognitive distortions, the kind of all-or-nothing thinking described in CBT. Underneath them lives fear: fear of failure, of judgment, of not being good enough.

Nowhere is this more visible than in how clients approach diet and training. Many come in chasing what they’ve been told is “optimal”. The “cleanest” diet, the most advanced program, the recovery routine of a professional athlete, and on and on.

But “optimal” rarely translates to practical.

Life doesn’t bend around a plan that rigid, so clients get trapped in black-and-white thinking: either they’re following the “perfect” program or they’ve blown it completely. That cycle alone derails progress, but there’s also a physiological cost. Living under constant pressure to “do it right” keeps the body in a state of stress, raising cortisol, disrupting recovery, impairing sleep, and ironically making results harder to achieve.

Of course, all of this is reinforced by the culture we live in. Scroll through Instagram or TikTok and you’ll find endless examples of shredded physiques, extreme transformations, and “no excuses” mantras. The underlying message is that perfection is possible, and if you don’t achieve it, you’re just not working hard enough.

The irony is that even incredibly smart, educated clients, and people who know better, still get caught comparing themselves to those curated snapshots. Aspirational media can motivate in the short term, but for most people, it eventually undermines consistency. They chase an image that isn’t real, and when reality doesn’t measure up, shame takes over. This can be incredibly psychologically jarring and difficult to deal with.

As a coach, understanding this psychology is crucial. Your clients aren’t lazy or weak when they stumble. They’re just fighting dragons that were never real to begin with. And your job is to help them put down the lance, step back from the windmill, and build a relationship with health and fitness that’s grounded in reality, resilience, and self-compassion.

As Stoicism teaches us, much of suffering comes from confusing what is within our control with what is not. Perfection in body or performance is not fully controllable, but how we respond, adapt, and act is. Coaching is a natural extension of these Stoic teachings. We help people let go of the illusion of control over externals and focus on agency in daily choices.

Spotting Quixotic Ideals in Clients

Recognising quixotic ideals in your clients is one of the most important skills you can develop as a coach. These patterns aren’t always obvious at first glance. On the surface, a perfectionist client can actually look like your dream client. They’re disciplined, hardworking, and always “on it”. But if you really listen closely to their language, watch how they behave over time, and pay attention to what goes unsaid, you’ll start to notice the cracks.

Spotting these red flags early can save your clients from cycles of frustration and can help you guide them toward a healthier, more sustainable path.

One of the clearest giveaways is language. Clients caught in perfectionist thinking use words like “should,” “must,” or “perfect” all the time. “I should be meal prepping every Sunday.” “I must get all my steps in or the day is wasted.” “This plan is perfect, and if I stick to it, I’ll finally make progress.” These phrases reveal rigid expectations and a lack of flexibility, which almost always leads to disappointment. Along with the words, watch the patterns. You’ll often see stretches of rigid adherence (hitting every workout, tracking every calorie) followed by an all-or-nothing crash. When perfection slips, even in a small way, they abandon the whole plan.

Another telltale sign is persistent dissatisfaction despite measurable progress. You’ll point out that their strength is improving or their consistency is miles ahead of where it was, but they brush it off because it’s not perfect enough.

Sometimes the signals are subtler, especially when clients mask their struggles. Instead of admitting they’re overwhelmed, they’ll use guilt-driven excuses: “I’ll try harder next week.” They may downplay missed workouts or lapses in nutrition as if they’re insignificant, even though they clearly feel the weight of them.

In some cases, clients will perform “success” for the coach, such as reporting compliance, posting wins, or saying all the right things, all while privately struggling to keep up. This is where trust and rapport become essential. If clients don’t feel safe being honest about their imperfections, they’ll keep performing instead of progressing.

Existentialists like Kierkegaard and Sartre might call this living in “bad faith”. These clients are shaping their identity around the expectations of others rather than their authentic values. In coaching, we often must help clients move away from this performance of perfection toward choices that are actually rooted in their own agency.

The final nuance to pay attention to is the difference between aspiration and self-sabotage. Healthy striving is ambition that fuels growth. It pushes clients to challenge themselves, but it’s flexible and resilient in the face of setbacks.

Quixotic striving, on the other hand, is built on impossible standards. It’s brittle. Instead of building confidence, it breeds shame. The same ambition that could drive a client forward ends up driving them into a wall.

Your job is to discern which version you’re seeing: is this client motivated in a way that will support long-term progress, or are they chasing a dragon that will leave them burned out and defeated?

As coaches, the sooner you can recognise the signs of quixotic ideals, the sooner you can help reframe them into something that actually works. That’s where the coaching relationship moves from programming to true transformation.

Coaching Strategies to Address Perfectionism

Once you can spot quixotic ideals in your clients, the next step is knowing how to coach them through them. This is where your role moves beyond sets, reps, and macros and into mindset work. The goal here isn’t to eliminate ambition, it’s to reshape it into something sustainable. Clients don’t need you to strip away their drive. No. They need you to redirect it so it actually works in the real world.

A good place to start is with awareness. Most clients don’t realise how much perfectionist thinking shapes their behaviour until you hold up a mirror. Reflective coaching is powerful here. If a client says, “I should be training harder,” you might respond with, “I hear you used the word ‘should’ there. Where do you think that expectation is coming from?”

This type of gentle mirroring interrupts automatic thinking and creates space for curiosity instead of judgment.

Approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) emphasise noticing thoughts without having to buy into them. You can teach clients to see perfectionist thoughts as passing mental events, not absolute truths that must dictate behaviour.

From there, one of the simplest but most transformative tools you can use is language reframing. “Should” implies obligation, pressure, and shame if the standard isn’t met. Swapping it for “could” changes everything.

Instead of “I should work out every day,” the client can say, “I could move in some way today.” The shift is subtle but actually quite profound. It moves the thoughts from an obligation to choice, from pressure to agency. It empowers flexibility without losing direction. Clients start to see options instead of ultimatums, which is where sustainable consistency grows.

You’ll also need to help clients prioritise realism over idealism. Translating “optimal” into “sustainable” is one of the most valuable skills you can offer. The truth is that perfect plans rarely survive the chaos of real life. Teaching clients the 80/20 principle, and that 80% consistency with habits will carry them much further than 100% effort followed by burnout, gives them permission to succeed imperfectly. Remind them daily that “progress, not perfection” isn’t just a nice slogan; it’s the actual formula for long-term success.

Aristotle’s Doctrine of the Mean reminds us that virtue is found between extremes. Discipline in fitness is valuable, but when pushed to excess, it becomes destructive perfectionism. At it’s best, coaching mirrors Aristotle’s idea of practical wisdom (phronesis), and we can help clients discover the “mean” that is sustainable in their real lives.

Another critical piece to all of this is self-compassion. Many clients equate compassion with weakness, as if being kind to themselves means making excuses. You need to dismantle that myth. Research is pretty clear that self-compassion improves adherence, resilience, and long-term outcomes. A client who can bounce back from a missed workout with curiosity instead of self-loathing will stay consistent far longer. Practical tools here include self-talk reframes (“I missed one workout, but I’ve been consistent all month”), journaling prompts that highlight effort as much as results, and celebrations of small wins instead of only big milestones.

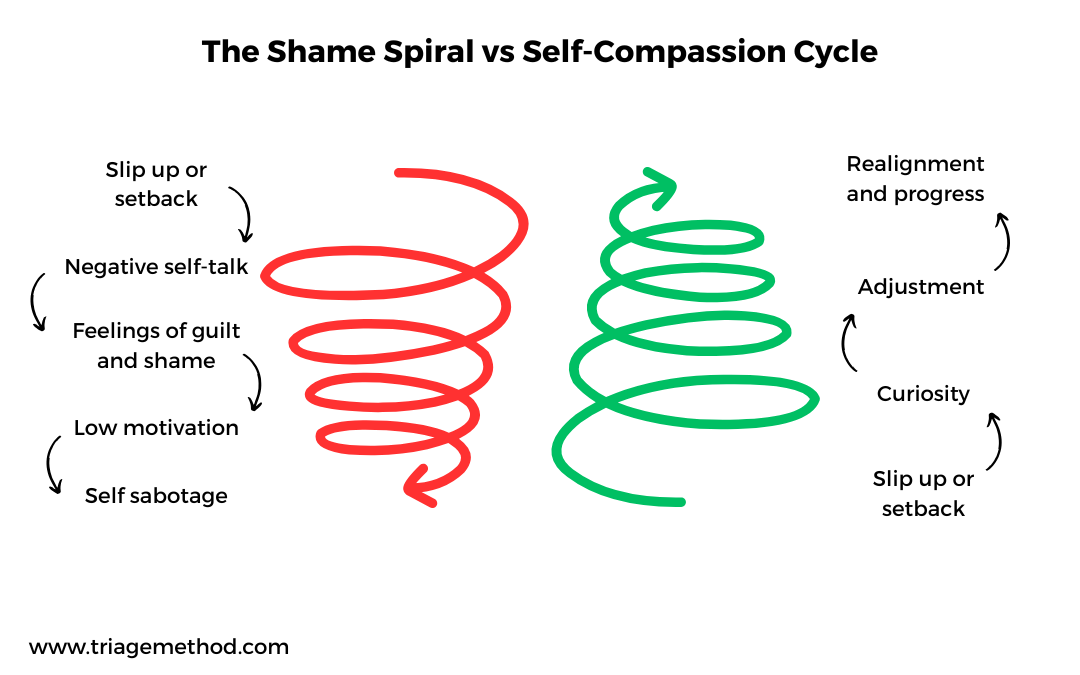

Finally, you have to address the shame spiral that perfectionism often creates. Slip-ups are inevitable, but for a perfectionist, they feel like proof of failure. Your role is to normalise them as data, not moral failings. Use “fall forward” language, and teach that every stumble is feedback, not a setback. When clients replace guilt with curiosity (“What can I learn from this?” instead of “What’s wrong with me?”) they begin to break free of the destructive cycles that hold them back.

In short, your strategies for addressing perfectionism come down to awareness, reframing, realism, compassion, and curiosity. These aren’t soft add-ons to your coaching, they’re the actual backbone of coaching.

Practical Tools and Exercises

It’s one thing to talk mindset, reframes, and compassion, and it’s another to give clients concrete tools they can actually use. If you want to dismantle quixotic ideals in a meaningful way, you need frameworks that translate philosophy into practice. These tools don’t just keep clients on track; they give them systems to navigate real life without falling back into perfectionism.

A good starting point is goal-setting, but not in the generic “SMART goals” sense most people already know. Instead, think in terms of minimum effective dose. Ask what’s the smallest, most realistic step that would still move this client forward? Differentiate between outcome goals (“I want to lose 10 pounds”) and process goals (“I will strength train three times per week”).

Then scale them using a simple framework: best case, realistic case, and minimum. For example: best case, they hit four workouts; realistic case, three; minimum, one solid session. This scaling makes progress feel accessible instead of all-or-nothing.

From there, help them build flexible planning systems. I like the idea of “floor and ceiling” goals. The floor is the minimum baseline, and should be something so achievable that they can hit it even on their busiest, most chaotic week. The ceiling is a stretch goal for when life opens up space. This structure gives clients permission to adapt while still moving forward. Flexibility also means designing routines that can survive travel, kids’ schedules, illness, and stress.

A coach’s job isn’t just to help clients succeed when life is smooth, it’s to help them succeed even when life is messy. In fact, adaptability itself should probably be treated as a performance metric. Can this client stay in the game even when circumstances are challenging? Or are they only able to do the plan on a perfect week?

Feedback loops and check-ins are another goldmine. This is where you normalise imperfection. During reviews, don’t just ask, “Did you stick to the plan?” Instead, explore: “What went well? What got in the way? What did we learn?” Celebrate adherence to intent, not just outcome. If a client planned four workouts but only got two because their child was sick, that’s not failure, it’s just data. Those challenges are coaching gold because they show you exactly where the plan needs to flex. Clients who internalise this view stop fearing setbacks and start treating the whole process as a series of experiments.

Lastly, give clients reflection and reframing tools they can actually use between sessions. A simple language swap worksheet (turning “should” into “could,” and “could” into “choose to”) builds awareness around agency. A values clarification exercise helps them connect daily actions to deeper reasons why health matters to them, so their choices aren’t just about calories or exercises but about living in alignment with who they want to be. Prompts like, “What would good enough look like today?” help ground them in reality instead of chasing perfection.

And for inevitable slip-ups, a three-step reframing template works wonders: What happened? What did I learn? What’s next? This turns every stumble into an action plan instead of a failure spiral.

The power of these tools is that they give structure to the messy process of behaviour change and help clients see that imperfection isn’t the enemy, and that it’s part of the process.

Real-World Coaching Scenarios

Theory is only useful if it translates into practice. To bring these ideas to life, let’s look at three real-world coaching scenarios. Each illustrates how quixotic ideals show up in different client populations, and how you, as a coach, can help dismantle them.

Case 1: The Corporate High-Achiever

The Situation: A corporate executive came to me with a common pattern: all-or-nothing nutrition. She had the resources, the discipline, and the motivation, but every time she started a new diet, it went the same way. Two to three weeks of flawless eating, followed by a crash. When she inevitably slipped (a business dinner, a stressful week of travel), she felt she had “blown it,” and the entire plan unravelled.

Language Cues & Psychology: Her language was filled with absolutes: “I have to stick to the plan exactly.” “I ruined it by having dessert.” “If I can’t do it 100%, what’s the point?” This was classic black-and-white thinking, driven by self-oriented perfectionism. Underneath, the fear was that if she wasn’t perfect, she’d never make progress.

Coaching Response: Instead of layering on another “perfect” meal plan, I introduced the concept of minimum effective habits. We scaled her nutrition goals into tiers: best case, she prepped full meals; realistic case, she made balanced choices while travelling; minimum, she hit a serving of protein and a serving of vegetables at every meal. I mirrored back her “I ruined it” language and reframed: “You didn’t ruin anything. You met your minimum tier, and that counts as progress.”

Other Tools Used:

- Floor-and-ceiling nutrition goals.

- Weekly reflection prompts: “What went well despite challenges?”

Reframe Achieved: She shifted from seeing missed perfection as failure to seeing flexible consistency as success. Over time, her adherence improved, and not because she worked harder, but because she stopped quitting every time life got in the way.

Case 2: The Young Athlete

The Situation: A collegiate athlete wanted to “optimise” everything: training twice a day, strict macros, supplements, biohacks, the whole works. His drive was impressive, but he was constantly fatigued, struggling with minor injuries, and plateauing in performance.

Language Cues & Psychology: He often said things like: “If I’m not doing everything possible, I’m falling behind.” “Other athletes are grinding harder than me.” This revealed socially prescribed perfectionism, and his self-worth hinged on measuring up to others. Fear of inadequacy fueled his obsession with doing more.

Coaching Response: Instead of validating his push for “optimal,” I redirected the conversation to longevity and recovery. I explained how constant overload was spiking stress, impairing adaptation, and keeping him stuck. We reframed his ambition: “True high performers know when to pull back, not just when to push.” I introduced recovery as part of training, not the opposite of it.

Other Tools Used:

- Education on stress physiology and overtraining.

- Reframing “more” into “better” (quality over quantity).

- ACT-style noticing: helping him observe the thought “I’m falling behind” without automatically obeying it.

- Scaling training goals to include recovery targets (sleep hours, mobility work, rest days).

Reframe Achieved: He began to see recovery not as weakness but as a competitive advantage. Instead of burning out, he started progressing again by focusing on the long game. He shifted from “I must do everything” to “I do what matters most.”

Case 3: The Busy Parent

The Situation: A parent of three, juggling work and family responsibilities, came to coaching feeling stuck in “shoulds.” She constantly said she “should” be meal prepping, “should” be training five days a week, “should” be more disciplined. Her guilt was high, her energy was low, and she struggled with consistency.

Language Cues & Psychology: Nearly every sentence started with “I should.” Underneath, she carried socially prescribed perfectionism, shaped by cultural ideals of what a “fit parent” ought to look like. Her real fear was judgment, and falling short as a role model for her kids.

Coaching Response: My first step was to swap “should” for “could” and “choose to.” Instead of “I should work out every day,” we reframed it as, “I could choose a short workout today, or choose to prioritise sleep.” We built flexible baselines: minimum two workouts a week, with options to do more if life allowed. I also highlighted wins she dismissed, for example, walking with her kids counted as movement worth celebrating.

Other Tools Used:

- Language swap: “should → could → choose.”

- Best case/realistic case/minimum scaling for both workouts and nutrition.

- Reflection prompt: “What would good enough look like today?”

- Values clarification: linking fitness not to aesthetics, but to being present and energised for her family.

Reframe Achieved: She stopped equating missed workouts with failure and started seeing consistency as something that could flex with her lifestyle. By grounding her actions in family values, her guilt transformed into purpose. She learned that being a role model wasn’t about perfect discipline, but about showing her kids resilience and balance.

Each of these cases illustrates the same principle: perfectionism looks different depending on the client, but the coaching response follows the same pattern. Listen for the language, understand the psychology underneath, respond with compassion, and provide tools that reframe impossible standards into sustainable ones.

When you do this well, you don’t just help clients hit goals, you help them build health-based identities that can thrive long after the coaching program ends.

Boundaries and Red Flags

One of the hardest lessons to learn as a coach is that you can’t solve everything with better programming, smarter nutrition plans, or sharper accountability systems. There are times when perfectionism goes beyond the scope of fitness coaching and crosses into clinical territory. Knowing where that line is, and having the confidence to act on it, is part of what separates a good coach from a great one.

Perfectionism by itself isn’t a diagnosis, but it can fuel behaviours that are unhealthy and even dangerous. If you start noticing patterns like disordered eating, compulsive training, or symptoms of anxiety and depression, that’s your signal to step carefully. A client who skips meals, hides food, or panics at the idea of breaking their plan isn’t struggling with willpower, they’re showing warning signs. A client who refuses to rest despite injuries, or spirals into guilt and hopelessness after a missed workout, may need more than your coaching can provide. This is when it becomes your responsibility to pause, adjust, and sometimes redirect their goals to protect their health.

Referring out to a mental health professional is one of the most compassionate things you can do for a client, but it’s also one of the hardest. Many coaches hesitate, fearing it will damage the relationship. In practice, the opposite is true when you frame it with care. Instead of presenting it as a rejection, position it as an act of support: “I want the best for you, and some of what you’re experiencing deserves help beyond what I can responsibly give. A therapist can give you tools I don’t have, and I’ll still be right here as your coach.” This way, clients understand you’re not abandoning them, you’re strengthening the team around them. In fact, many clients feel relief when a coach acknowledges the limits of their role, because it validates that what they’re experiencing is real and deserves proper care.

A different but equally important red flag is when clients start performing success for you. This happens when they feel they need to please you rather than do the work for themselves. They polish their updates to sound perfect, downplay struggles, or say what they think you want to hear. On the surface, it can look like discipline, but underneath it’s often fueled by socially prescribed perfectionism and the need to appear flawless in someone else’s eyes. If you miss this, you end up coaching the performance instead of the person.

The solution is to create a coaching environment where honesty is valued more than perfection. Make it clear that you don’t need to be impressed, you need to be informed. Say things like, “I can only help with what’s real,” or, “Challenges aren’t failures, they’re the most valuable part of coaching.” When clients realise they don’t have to earn your approval, they stop curating their updates and start being honest. That’s when the real coaching can actually begin.

Ultimately, your job is not to diagnose or treat mental health conditions, but to recognise when perfectionism turns harmful and guide clients toward the right support. And within your own scope, your job is to build trust so clients know they can show up as their imperfect, authentic selves.

Meta-Coaching: Helping Coaches Break Their Own Quixotic Ideals

It’s easy to read everything we’ve covered so far and think only about clients. But the truth is that coaches aren’t immune to quixotic ideals either. In fact, we often fall into them ourselves, and when we do, they shape the way we work with clients. If you want to become a world-class coach, you have to be willing to shine the same light on your own perfectionism that you ask clients to shine on theirs.

One of the most common traps is what I call the coach’s curse: projecting our own training or nutrition standards onto clients. If you thrive on two-hour lifting sessions, it’s tempting to assume your client can or should thrive on the same. If you love tracking macros down to the gram, you might unconsciously build that into every plan you write. This is how we slip into our own version of the “optimal” trap, forgetting that what’s optimal for us is not necessarily optimal, or even realistic, for the people we coach. Recognising that bias is step one.

The antidote is humility and curiosity. Instead of prescribing from the top down, start by asking. Ask about their life, their stressors, their values, their time, their priorities. Coaching is most powerful when it’s a partnership, not an authority dynamic. Clients aren’t blank slates waiting to be filled with your expertise, they’re collaborators who bring their own expertise about their lives. When you embrace that, your coaching shifts from compliance-driven to client-centred.

This is also where your broader philosophy as a coach matters. If your philosophy is built on sustainability, joy, and adaptability, you won’t be as tempted to impose rigid ideals on your clients. And if you’re willing to model imperfection by sharing your own missteps (within appropriate boundaries), you give clients permission to do the same. It’s not about oversharing or making the session about you, but about humanising the process. When a client sees that even their coach isn’t flawless, it makes their own journey feel more achievable.

Ultimately, coaching isn’t about short-term wins; it’s about helping someone build a life they can actually live in, not just endure for twelve weeks.

Of course, there’s another dimension to this, which is your own well-being as a coach. Perfectionism doesn’t just burn out clients, it burns out coaches too. You might feel pressure to always have the perfect answers, the perfect programming, or to never let a client struggle. You might measure your worth by your clients’ outcomes, forgetting that you can’t control every variable in their lives.

This “I must be the perfect coach” mindset is just another quixotic ideal. The cure is the same as with clients: self-compassion, realistic standards, and permission to be human. Building reflective practices, setting professional boundaries, and celebrating effort instead of only results keeps you from collapsing under the same pressures you’re trying to help your clients escape.

Meta-coaching means holding up a mirror not just to your clients, but to yourself. The more you dismantle your own perfectionism, the more authentically you can guide others through theirs.

A few prompts to help you start thinking about this are:

- “Where do I impose my own ‘optimal’ on clients?”

- “When do I find myself frustrated with client imperfection, and what does that reveal about me?”

- “What unrealistic expectations do I hold for myself as a coach?”

Conclusion: Coaching Beyond Perfection

At the end of the day, coaching isn’t about chasing flawless plans or sculpting perfect bodies, it’s about helping real people build lives they can actually live in. Dismantling quixotic ideals is central to that mission. As long as clients are tilting at the windmills of perfection, they’ll stay trapped in the cycle of all-or-nothing effort, guilt, and burnout. But when they learn that imperfection is not the enemy, it’s the literal path they must walk on, they finally unlock the consistency they’ve been missing all along.

This is why the work goes deeper than sets, reps, or macros. It’s about teaching clients that progress is messy, flexibility is strength, and setbacks are part of the process. When they learn to treat slip-ups as data instead of failures, to swap “should” for “could,” and to embrace self-compassion over shame, they build habits that are not only resilient but self-sustaining.

The ultimate aim of coaching is not to create adherence to a perfect plan. It’s to help clients design a lifestyle that adapts to the realities of human life, with its travel, kids, illnesses, work stress, holidays, and unpredictability. When clients can keep moving forward through all of that, even imperfectly, you’ve given them something far more valuable than a temporary transformation. You’ve given them the skills and mindset to thrive for the long game.

Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus offers a fitting image here. You don’t want your clients endlessly rolling the boulder of perfection uphill, only to watch it fall. Unlike Sisyphus, clients chasing quixotic ideals rarely find meaning in the struggle. Really effective coaching helps them step out of the cycle altogether and find progress in imperfection.

If you’d like to keep learning, we’ve put together a library of free resources in our Content Hub. Inside, you’ll find our Coaches Corner, which has a collection of practical tools, frameworks, and insights designed specifically for coaches who want to sharpen their craft. You can also connect with us on Instagram or YouTube, where we regularly share tips, strategies, and real-world examples to keep you inspired and equipped. And if you want to make sure you never miss a new resource, subscribing to our newsletter is the simplest way to stay current.

For those ready to go deeper into professional development, we also offer advanced training. Our Nutrition Coach Certification is built to help you confidently guide clients through sustainable, evidence-based nutrition change, while our Exercise Program Design Course focuses on creating effective, individualised training plans that work in the real world. Beyond that, we have a range of specialised courses so you can continue growing in the areas that matter most to your coaching journey.

And remember, coaching can feel like a lonely job sometimes, but you’re not alone. If you ever want to ask a question, get clarification, or simply connect, reach out to us on Instagram or by email. We’re here to support you as you keep building your skills, your practice, and the impact you make with your clients.

References and Further Reading

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Quixote

Curran T, Hill AP. Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychol Bull. 2019;145(4):410-429. doi:10.1037/bul0000138 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29283599/

Khossousi V, Greene D, Shafran R, Callaghan T, Dickinson S, Egan SJ. The relationship between perfectionism and self-esteem in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2024;52(6):646-665. doi:10.1017/S1352465824000249 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39279628/

Callaghan T, Greene D, Shafran R, Lunn J, Egan SJ. The relationships between perfectionism and symptoms of depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2024;53(2):121-132. doi:10.1080/16506073.2023.2277121 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37955236/

Liu Q, Zhao X, Liu W. Are Perfectionists Always Dissatisfied with Life? An Empirical Study from the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Perceived Control. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(11):440. Published 2022 Nov 10. doi:10.3390/bs12110440 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9687152/

Smith MM, Sherry SB, Vidovic V, Saklofske DH, Stoeber J, Benoit A. Perfectionism and the Five-Factor Model of Personality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2019;23(4):367-390. doi:10.1177/1088868318814973 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30612510/

Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Nepon T, Sherry SB, Smith M. The destructiveness and public health significance of socially prescribed perfectionism: A review, analysis, and conceptual extension. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;93:102130. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102130 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35216826/

Robinson A, Moscardini E, Tucker R, Calamia M. Perfectionistic Self-Presentation, Socially Prescribed Perfectionism, Self-Oriented Perfectionism, Interpersonal Hopelessness, and Suicidal Ideation in U.S. Adults: Reexamining the Social Disconnection Model. Arch Suicide Res. 2022;26(3):1447-1461. doi:10.1080/13811118.2021.1922108 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34019781/

Casale S, Svicher A, Fioravanti G, Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Pozza A. Perfectionistic Self-Presentation and Psychopathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2024;31(2):e2966. doi:10.1002/cpp.2966 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38600830/

Powers TA, Koestner R, Zuroff DC, Milyavskaya M, Gorin AA. The effects of self-criticism and self-oriented perfectionism on goal pursuit. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37(7):964-975. doi:10.1177/0146167211410246 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21632968/

Stoeber J, Childs JH. The assessment of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: subscales make a difference. J Pers Assess. 2010;92(6):577-585. doi:10.1080/00223891.2010.513306 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20954059/

Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(3):456-470. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2027080/