Understanding periodisation is the key to making long term progress.

In an article in this series, on designing an actual workout, we walked you through how to design a single workout and a week of training. But you are unlikely to get results within a week. So you have to learn to organise your training over the longer term. So, in the previous article on Training Progression (Progressive Overload) we covered the basics of actually progressing your training.

So you do have a lot of information to work with, however, what is missing is an understanding of how to organise your training over weeks/months/years. This is where periodisation comes in.

Ultimately, it takes a long time to actually see meaningful results, and there are much better and worse ways of organising your training over a longer period of time.

If you haven’t already, it would be incredibly helpful to also read our articles on why exercise is important, the goals of exercise, the types of exercise we have available to us, and to have a rough idea of the general exercise guidelines. It would also be incredibly beneficial to visit our exercise hub, and read our content on resistance training and cardiovascular training, along with the rest of the articles in this series. Reading the articles on designing an actual workout and especially Training Progression (Progressive Overload) would also be ideal before you read this article.

Before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Now, let’s get stuck into understanding periodisation!

Table of Contents

Periodisation

We previously discussed how to organise a training session and a week of training, but the reality is that progressing your training is realistically a multi-year endeavour. So you need to know how to organise your training over longer periods of time. This is where periodisation comes in.

Periodisation is simply how you structure your training over the longer term. There are a number of ways you can periodise your training, and this is dependent on why exactly you are periodising your training. You will generally see periodisation discussed with regards to athletes, but it is actually very applicable to the general trainee. However, the exact specifics of how a periodisation plan is implemented may be different.

With regards to athletes, periodisation is simply the systematic approach to structuring their training program to optimise performance and achieve specific goals at specific times. At its core, periodisation involves strategically manipulating training variables, such as intensity and volume, to better manage the balance between stimulus and recovery.

This is very often done in distinct “blocks” of time (or periods, hence the name). By organising training into distinct phases or cycles, athletes can better ensure that they peak (e.g. are at their best) for important events or competitions while also addressing the various training objectives that go into peak performance.

By breaking down a larger goal into smaller distinct blocks, athletes can focus their attention on progressing towards different goals at different times, while maintaining their performance at other goals. This allows them to prioritise the goals that are most relevant to their performance objectives at any given time. Rather than attempting to pursue all training goals simultaneously, periodisation allows for the progression of different qualities while maintaining others as maintenance goals.

Now, you may not think this approach can be of benefit to you, who just wants to be a bit fitter and get a bit leaner. However, understanding how to use periodisation is actually incredibly useful to everyone who trains.

While you may not need to peak for a specific event, you do need to have some way of managing fatigue and stimulus. This is something that a lot of people struggle with, and in our coaching practice, we very often deal with people who constantly cycle between being “on track” and being “off track” because they don’t use periodisation.

These people just try to push hard, they take on too much, and then they have no way to manage the fatigue that accumulates. Oftentimes they just try to push harder, and eventually, the wheels fall off the wagon. When we implement some degree of periodisation, it is much easier to actually manage the training over a longer period of time, and thus it is much more likely that you will get results from training.

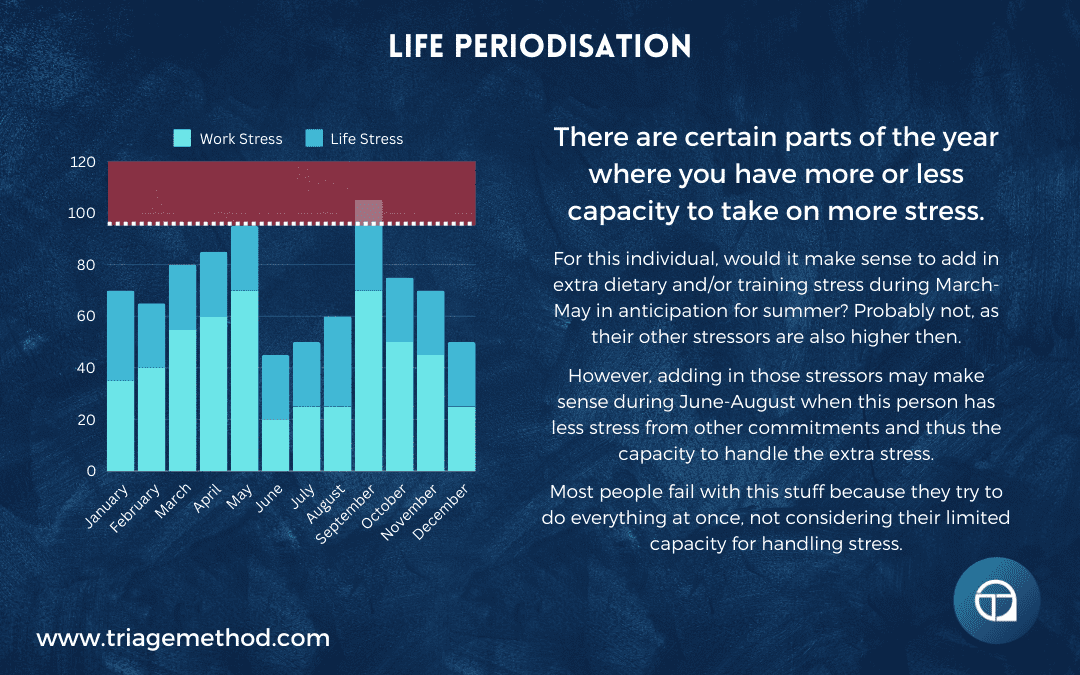

Most of you will also have a variety of goals. You also likely have different things going on at different times of the year. So having a periodised training plan that takes this into account is likely going to result in much better results.

For example, maybe you are much busier at work during the summer months, and your stress is much higher than the rest of the year. Does it make sense to do your most intensive training at this time of year? Probably not. Would it make sense to plan to reduce your training volume/intensity during this time, to allow for more recovery? Almost definitely.

We discussed this in the stress management article, as it relates to life periodisation, but the same concepts hold true here.

This is periodisation. You are simply organising your training into distinct periods, to better account for the different things you have going on during the year. This isn’t just about knowing when to pull back, it is also about knowing when to push forward. At other times of the year, you may be able to really progress your training, or you may simply have more time to train. You can take advantage of this natural fluctuation in your ability to push training, by having a periodised plan in place.

Periodisation also allows you to be more systematic about how you intend to progress things. At certain times you may be focused on progressing your strength, whereas other times you may be more focused on progressing your aerobic fitness. By having a periodised plan in place, you can do some reverse engineering of how you would need to progress your strength each week to hit your target strength numbers, before you switch your attention to more aerobic training.

Over-Training

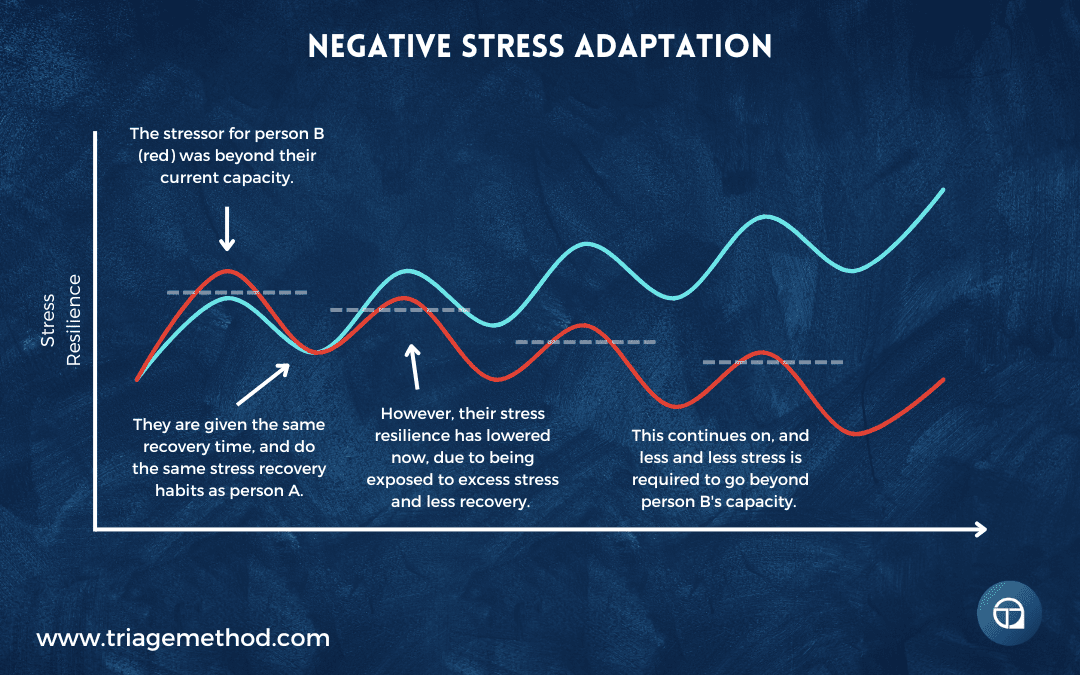

To understand periodisation, we also have to just touch on the topic of over-training. Overtraining is a situation where the adaptations you are hoping for do not occur due to training more than your body is able to recover from. So despite the high level of effort that is being put in, the results are less than expected because the body has not adapted due to excess stress and insufficient recovery.

This is a real phenomenon, but people tend to think of it like an on-off switch, rather than a dimmer switch. You see, most people under-recover, and see results that are below what they could achieve. This is further compounded by the fact that most people also over-stress. However, they still see some progress, so they assume everything is all good. But they don’t realise that they are actually seeing a small percentage of the results they could obtain if they were to actually recover from their training.

This is actually why most athletes turn to performance-enhancing drugs, notably anabolic androgenic steroids. It isn’t so much the performance-enhancing aspects of these drugs that they are seeking, it is the recovery-enhancing effects. By taking these drugs they can continue to engage in higher training volumes and still recover. Those of us that do not have the advantage of using these drugs should really be focusing on ensuring recovery and stress levels are managed, so that we are actually able to adapt to the training stimulus. This may actually mean that we need to reduce our training volumes, to a level that we can actually recover from.

However, it is very hard to actually overtrain, once you give yourself sufficient time to adapt. And therein lies the real issue. Most people are not giving themselves enough time to adapt, and are not focusing on the recovery element enough. They are trying to train like an Olympian, while having a stressful day job, a demanding family life and sleeping 6 hours a night.

Again, this is the very same concept discussed in the stress management article, and it is just a classic case of “negative stress adaptation”.

They also usually aren’t slowly titrating the training volumes up over time, instead, they jump into high training volumes quickly, then fall apart after a few weeks and surmise that it was over-training that caused the issue. It was, but it was really the fact that they did not provide enough recovery time to allow their bodies to adapt to the training.

If you look at the training volumes of elite athletes, the volume of work they are doing now, has been built up over years. Trying to copy what they are doing now isn’t going to lead to the same outcomes it does in them, because you simply lack the years of adaptation that they have gone through to be able to handle those training volumes.

It should also be noted that it is much easier to over-train by virtue of too much volume of work, than it is to over-train by virtue of too high an intensity of work. With intensity, you are usually quite limited by how much you can actually overload the body. You can only lift a certain amount of weight or perform cardio so intensely before performance drops off. However, you can basically do a near unlimited amount of lower intensity volume, without seeing much drop off in performance (at least in the short term). The biggest issues occur when people try to do high volumes of high intensity work.

As we discussed previously, you are actually adding a significant amount of extra stress when you do more volume. This can be positive, in that it can be used to drive adaptations. However, you can very easily tip beyond your recovery capacity if you are not careful.

One of the key attributes that distinguishes amateur athletes from elite athletes is the ability to effectively manage their stress inputs. Knowing when to push and when to pull back, and knowing how hard to train on a given day within a larger training program is the hallmark of the elite. Whereas amateur athletes think they can progress faster by simply working harder. Generally, this just leads to quick burn out or injury.

For training, we don’t generally tend to maximise for intensity of work, we maximise for the ability to do that work for weeks/months/years. Training adaptations take time, and while you can actually improve a lot in a short space of time, you really need to be thinking over a longer time frame if you want to be successful, and this generally means being able to manage the various training stress and recovery (i.e. know when to push and when to pull back).

This is where periodisation comes in.

Block Periodisation

There are multiple (and I mean 100’s if not 1000’s) ways to structure a periodisation model, and as always it has to pay respect to the athletic goals and the individual’s unique needs. It must not only take into account the anatomical and physiological systems we are trying to create adaptations in, but also the psychological aspects and schedule of the individual.

Generally, periodisation is talked about in terms of macrocycles, mesocycles and microcycles. Technically, we have already spoken about microcycles when we talked about the organisation of the training week. Macrocycles are more concerned about the yearly plan, and long term goals. Discussing macrocycles in depth would require a lot more information, as it is specific to an individual’s needs and goals (and I don’t know your specific needs and goals).

So when talking about periodisation, we are left to talk more about mesocycles. These are generally 1-8 week long phases that look to achieve a specific adaptation or goal by the end of them. This could be increased muscle, increased endurance, increased power, increased relative strength etc. The exact way you go about organising the training within each of these mesocycle blocks depends on the specific adaptations you are trying to target. It must also pay respect to the blocks that came before it, and those that you intend to do after it.

This will make more sense if I elaborate a little bit more. In general, within periodisation models, there are roughly 4 types of “blocks”:

- Accumulation

- Intensification

- Deloading/Detraining

- Tapering

Now before I get further into each of these concepts, as always, you must realise that like everything in the world, there is a lot of overlap between these different aspects. You could be in an accumulation phase that would be the intensification phase of another individual, or you could be in an intensification phase that only mildly tapers into a less important competition/event. So there are shades of grey, and it isn’t black and white.

So what do each of these concepts mean?

Accumulation

Accumulation phases are generally periods of training that are characterised by higher volumes of training, and a lower intensity level. The goal is to accumulate volume, hence the name. Depending on the goal an accumulation phase may have a higher number of exercises, higher number of sets, higher total volume, and lower intensity (% of 1RM). But of course, the accumulation phase of a bodybuilder will look different than the accumulation phase of a powerlifter. As a very general rule, accumulation phases are generally designed to create structural/anatomical adaptations (i.e. grow muscles or create new mitochondria).

Intensification

Intensification phases are generally periods of training that are characterised by low volume of training but a higher intensity (hence the name). The goal here is to lift heavier weights or push to higher intensities with cardio. As a very general rule, intensification phases are designed to be more neural in nature when we talk about lifting weights (i.e. become more efficient in how your body handles weights) and more anaerobic when we talk about cardio. Generally, lower reps are used, lower number of exercises and more sets are used, along with the higher intensity of load.

Deloading/Detraining

Deloading or detraining as a concept to get bigger, stronger or fitter sounds a bit strange when you are first exposed to the concept. I mean how can training less, or not training at all, make me bigger, stronger or fitter? Well if you are training hard (whether you are in an accumulation or intensification phase) you will generally be building up significant stresses on the body, and having a period of “easier” training will allow some of these stresses to dissipate. The goal of deloading is to allow the stress on the body to dissipate enough so that when you return to training you are feeling both mentally and physically ready to hit it hard.

Detraining is essentially deloading taken to the next step. Detraining is allowing the adaptations you have developed to dissipate. This for some may seem a very silly concept, especially those involved in bodybuilding. Why would you ever wish to lose what you worked hard for? Well just like deloading it allows the individual to come back fresh and ready to go again. Consider the bodybuilder Kevin Levrone who supposedly used to not train for 6 months of the year, lose significant muscle, and then the 6 months before competition he would “grow into the show” and absolutely dominate. He said the time off from training was needed to give him the drive and motivation to come back and train with the intensity to win 23 Pro Shows and become one of the all-time best Pro Bodybuilders.

Tapering

Tapering (or sometimes called peaking) is similar to deloading, but it is more specific in its application. We want to taper for an event, and be in peak physical condition for it. We want to allow some of the accumulated fatigue to dissipate, but not so much that we are left detrained. Every sport has unique tapering demands, and as such, it would be impossible to give specific recommendations in a general article. For powerlifting, it may mean having a relatively heavy, non-fatiguing workout the Monday before the competition. Whereas for bodybuilders it may mean not training heavy/hard the week of competition, and perhaps targeting some body parts specifically (along with strategic carb loading) to achieve the look required on show day. For endurance sports, or field sports, the tapering may look wildly different.

Block Periodisation Overview

Ultimately, these are a little bit more relevant to athletes, although understanding the basic concepts are actually quite useful for the every day trainee. While you likely aren’t going to be creating a complex periodisation system that has blocks of accumulation, intensification, deloading, detraining and/or tapering, you are likely going to want to periodise your training so that you are actually working towards the various goals that you have and respecting your overall recovery capacity at different times of year.

You may also use block periodisation in a slightly different way, and instead of using it to better manage fatigue, you may use it to strategically work on different goals across the year. For example, you may spend the autumn and winter time focusing on building up your strength and muscle mass, while only keeping your aerobic fitness training at a baseline minimum. But during the spring and summer time, you may switch this and focus more on building your aerobic fitness, while doing the minimum to maintain your strength and muscle size.

The benefit of breaking down training into distinct blocks is that it allows you to better manage fatigue, but it also allows you to work more intently towards a specific goal rather than trying to chase multiple goals at the same time. There is a classic saying that “you can’t ride two horses with one ass”. Similarly, “you can’t serve two masters”.

Trying to achieve multiple goals at once generally just leads to slow progress (or no progress) on the goals, whereas it is much easier to just maintain a specific attribute and really push for progress on another attribute. Breaking training down into distinct blocks allows you to allocate your efforts more appropriately and progress faster towards your goals than if you tried to do everything at once.

Other Ways To Periodise

Now, not every periodisation model will use these same concepts, however, they are the foundational elements of many periodisation models. They do fall victim to the assumption that you will be using some sort of “block” periodisation, and are organising your training into distinct blocks. But this may not be the case. We do think most people would benefit from being more strategic with what they try to achieve across the year, and block periodisation allows for this. However, it is not the only way we can periodise our training.

You may only have 1 main goal that you are working towards, rather than multiple goals. As such, you may not break your training up into distinct blocks where you work towards completely different categories (i.e. strength, hypertrophy, aerobic fitness etc.). Instead, you could break your training up so you are working on specific attributes with the broader category you want to work on.

For example, perhaps your goal is to grow bigger muscles. You may spend 16 weeks working on adding size to your chest and quads, while the other main muscle groups are only getting maintenance volume. You may then switch the chest and quads to maintenance volume, and push the volume on your back and hamstrings.

This is still block periodisation, as you are allocating distinct blocks to work on specific goals, but the distinct goals are all still just under the same broader umbrella (in the above case, the umbrella goal is to get bigger). However, periodisation is not just about organising what your training focus is, it is also about managing the fatigue from training.

This can be done in a number of ways. Two frequently used periodisation models that accomplish this are waved loading periodisation and undulating periodisation.

Wave Loading

With wave loading, you basically progress one (or maybe two) of the variables in a stepwise manner over time, before dropping them back down. Usually this is done on a week to week basis, but it can also be done over longer periods of time 2+ weeks (however, it does basically just become block periodisation then). So for example, in week one of a training program, you may do something like 3 sets of 5 reps at RIR 2. Week 2 is then 3 sets of 3 reps at RIR 2. Week 3 is then 3 sets of 1 rep at RIR 2. Week 4 is then some sort of deload, or the process starts again. The second wave could potentially look to also progress the intensity further by manipulating the RIR. For example, week 1 of the second wave is 3 sets of 5 reps at RIR1, week 2 is 3 sets of 3 reps at RIR 1, and week 3 is then 3 sets of 1 rep at RIR 1. Ultimately, the loading progresses in a wave-like manner.

Undulating Periodisation

However, you can also manipulate fatigue by using an undulating periodisation model. This is quite similar to wave loading, although it generally involves manipulating 2 variables at a time, usually intensity and volume. The basic premise is straightforward enough, and you are basically manipulating 2 variables in opposition to each other, so the waves are out of phase with each other. So for example, a program utilising this may have intensity (reps and proximity to failure) and volume (number of sets) as the two variables. As intensity goes up, volume goes down, and vice versa. This can be done on a day to day basis, week to week basis, or even longer periods of time (but again, it does basically become block periodisation at some stage).

Now, while these are generally thought of as periodisation models, they are effectively just ways to more coherently implement a progression model. They are still focused on progressing certain variables, but they are just trying to organise things in a way that leads to better recovery between workouts and across time.

However, there are other ways to do this, and the way we generally like to accomplish this is with autoregulation. The benefit of autoregulation is that it doesn’t assume to know how well recovered you are for a given session, and it can be adjusted more easily. With the two above periodisation models, there is some degree of assumption baked in, where they presume to know how well recovered you will be and how much stimulus you can handle on a given day.

Autoregulation

Now, I don’t intend to go in depth on every possible periodisation model and its pros and cons. We can save that for another time. Instead, I want you to actually have a periodisation model that you can use. With most of our clients, we use an autoregulatory approach to training to accomplish this. Autoregulation is a form of periodisation, as it allows you to ensure you are providing the right amount of stimulus, while respecting the overall fatigue you are experiencing from previous training.

We discussed autoregulation when discussing progressing your resistance training and your cardio training, so I won’t do another deep dive here. However, the basic premise is straightforward enough.

The basic premise of autoregulation as a means to periodise training is to adjust training variables in response to your real-time readiness, performance, and recovery. Rather than strictly adhering to pre-planned training prescriptions, autoregulation allows you to modify training intensity, volume, and other variables (even down to exercise selection) based on your daily or weekly fluctuations in physical and psychological readiness.

By listening to your body’s signals and adjusting training accordingly, you can optimise the balance between training stimulus and recovery, minimise the risk of overtraining, and maximise long-term performance gains.

We use autoregulation with our online coaching clients because autoregulation empowers you to make informed decisions about your training based on your own unique physiological responses and training goals. This ultimately leads to more personalised programming and better training outcomes.

Autoregulation should be easy enough to understand, although it does take some getting used to. But once you start playing around with it, you will realise just how beneficial it is in allowing you to manage the stimulus you apply to the body. It allows you to stay more closely aligned with the level of stimulus that the body is actually able to perform on any given day.

The issue that people run into with autoregulation is when they try to marry autoregulation to a specific progression model. Many people still view progression with a beginner’s mindset, where they believe that progression is going to happen on a week to week basis.

Alternatively, many people believe that you can predict how fast you will progress, and try to extrapolate progression over time. This generally isn’t how the body works (it is a little bit more how the body works when you layer drugs into the mix, as you can manipulate the amount of drugs you take to force recovery and progression).

However, it should be too difficult to marry a progression model with an autoregulatory approach to your training. The first step is simply viewing autoregulation as knowing how to manipulate training variables based on how well you can perform on a given day, and how well recovered you are. With this knowledge, you can then better understand how hard you can push on a given training day.

Let’s assume you are using something like a double progression model where you are either increasing the number of reps you do, or the weight you use. Let’s assume you do 3 sets of 8 reps with 35kg in last week’s workout. With your double progression model, you are now looking to increase the weight you use.

However, you go into the workout after a poor night of sleep and you just don’t feel as recovered as you normally do.

With autoregulation, you now have a few options for how you approach this session, depending on how poorly (or well) recovered you feel. You may feel awful, in which case, you may actually just reduce the weight substantially, and do 3 sets of 8 with 20kg and basically just get some blood in the muscles.

However, let’s assume you just feel mildly under-recovered. In this case, you could stick to the same parameters you did last week. You haven’t recovered enough to actually progress, so it makes sense to apply the same stimulus you did the last time. You could also potentially increase the weight to the 37.5kg you intended to increase to, but instead of hitting the bottom end of the intended rep range (i.e. 6 reps), perhaps you keep more reps in reserve and you only do 4-5 reps with that weight. Alternatively, perhaps you feel good enough to increase the weight to 37.5kg, but you only do a single set of 8, rather than multiple sets. As you can see, there are many ways you could potentially manipulate the variables to reduce the overall fatigue generated from that workout.

Perhaps the week after, due to focusing on your recovery and not destroying yourself in the gym when under-recovered, you actually feel like you are ready to push for progress. In this case, you can push for more progress, depending on what exactly you did the previous week.

For example, you may have done 37.5kg for 3 sets of 4-5 reps last week, and this week, you go in and push to get 37.5kg for 3 sets of 6-8 reps. Maybe you reduced the weight dramatically last week, in which case, this week you may either do the 35kg for 8 reps that was done the previous week or you may go for the 37.5kg for 3 sets of 6-8 reps if you feel up for it. Maybe you reduced the number of sets you were supposed to do with the 37.5kg to a single set, in which case, this week perhaps you go for 3 sets at this weight.

Ultimately, we are just looking to provide the level of stimulus that we can actually recover from. Progress is rarely linear, and neither is recovery. You don’t always need to push as hard as possible to make progress. Autoregulation is easily married to a progression model once you realise that the progression model is just trying to provide you with rough guidelines to help you progress. The progression model is effectively drawing the lines, and autoregulation is how you stay colouring within those lines.

Deloads

The final thing I want to just touch on here is the use of deloads in a periodisation model. As noted previously, the goal of deloading is to allow the stress on the body to dissipate enough so that when you return to training you are feeling both mentally and physically ready to hit it hard. If you master autoregulation, frequent deloads become less necessary. However, even with autoregulation, deloads do still potentially have a place.

A deload generally involves reducing volume and/or intensity of the training stimulus, to allow for better recovery. This is what autoregulation does on a shorter time frame (i.e. day to day and week to week), however, sometimes fatigue can still accumulate to the point where deloading makes sense. This is more likely to happen if you are more aggressively pushing for progress. Even with sound autoregulation practices in place, it can still be hard to colour within the lines.

Even with aggressively pushing for progress, once all the other variables such as sleep, stress management, nutrition and hydration are dialled in, recovery can still be quite good, and deloads are not necessary. However, the reality is that most people do not have all the other variables dialled in. Most people aren’t sleeping enough, are over-stressed and don’t have their nutrition fully dialled in. As a result, fatigue is more likely to accumulate.

In the real world, where you have work and life stuff to deal with, it is unlikely that you will be able to perfectly manage your fatigue, even with perfect autoregulation. As a result, deloads can make sense.

The deloads can be scheduled ahead of time, whereby you may organise your training so you push hard for a predetermined number of weeks, and then deload. Many programs, especially ones where you are not getting direct coaching and thus not getting a coach monitoring things and providing frequent feedback, use pre-planned deloads.

However, you can also use more of an autoregulation approach to your deloads too. What I mean by this is you deload on an “as needed” basis. This is very helpful for people who have real world commitments, as it allows you to better account for those weeks where your work or personal life are just more stressful. But it should be noted that, if you are deloading very frequently (i.e. every 2-3 weeks), you are probably just trying to do too much.

You can also quasi-schedule your deloads. To do this, you basically plan for a deload every ~9 weeks, but if you need to take one before then, you do. If you don’t take a deload in the initial 8 week period, then you simply take it in the 9th week. This quasi-scheduling does allow for a lot of flexibility, and can be quite useful for those with busy lives.

What We Recommend For Periodisation

So, to wrap this all up, we generally recommend the following as it relates to periodisation.

It makes sense to look at your training over a longer period of time (i.e. a year) and to schedule your training to suit all the other stuff you have going on. You will get much better results if you actually take into account your yearly schedule and the periods of time when you know your stress and/or life commitments are going to be more/less.

Further to this, you may have multiple goals you want to accomplish. However, these goals may not be synergistic. So it may make sense to better periodise your training schedule so you fit things together at different times of year that are synergistic or make more sense to be working on at that time of year.

For example, during the winter when it is cold and rainy, perhaps you focus more on building your muscle and strength, and then when it starts to warm up during the spring and summer, you focus on building your fitness. You can still keep the other goals on maintenance mode while you shift your focus to a different goal, and this doesn’t mean you completely shift your focus entirely across the year.

Even when you have fewer goals, or when you are working towards a specific goal, it may still make sense to periodise your training into shorter blocks. For example, perhaps your goal is muscle building. While the program is designed around building muscle, at different times you may focus on different body parts. You generally can’t progress absolutely everything at maximum speed all the time, as this generally just leads to excessive fatigue and thus poorer results. As a result, it may make more sense to just progress one or two muscle groups preferentially at any given time, while keeping the other muscles on a maintenance level of work.

We generally recommend having clear guidelines for your training (e.g. the training variables such as reps, sets, RIR, etc.), and we recommend using an autoregulation approach to how you actually execute the program. We use autoregulation on the day to day to stay within the optimal stimulus/fatigue balance.

We then recommend having a plan for how you intend to use deloads. For most people, this can generally just be somewhat ad hoc and you just take deloads as and when needed. However, for those of you who are really aggressively chasing progress, you may want to have some sort of schedule for your deloads.

As with everything, there is always more to learn, and we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface with all this stuff. However, if you are interested in staying up to date with all our content, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter and bookmarking our free content page. We do have a lot of content on how to design your own exercise program on our exercise hub.

If you would like more help with your training (or nutrition), we do also have online coaching spaces available.

We also recommend reading our foundational nutrition article, along with our foundational articles on sleep and stress management, if you really want to learn more about how to optimise your lifestyle. If you want even more free information on exercise, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

The previous article in this series is about Training Progression (Progressive Overload) and the next article in this series is Exercise Program Design Overview, if you are interested in continuing to learn about exercise program design. You can also go to our exercise hub to find more exercise content.

References and Further Reading

Bishop PA, Jones E, Woods AK. Recovery from training: a brief review: brief review. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(3):1015-1024. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816eb518 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18438210/

Spiering BA, Mujika I, Sharp MA, Foulis SA. Maintaining Physical Performance: The Minimal Dose of Exercise Needed to Preserve Endurance and Strength Over Time. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(5):1449-1458. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003964 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33629972/

Lloyd RS, Cronin JB, Faigenbaum AD, et al. National Strength and Conditioning Association Position Statement on Long-Term Athletic Development. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(6):1491-1509. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001387 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26933920/

Stone MH, Hornsby WG, Haff GG, et al. Periodization and Block Periodization in Sports: Emphasis on Strength-Power Training-A Provocative and Challenging Narrative [published correction appears in J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Nov 1;35(11):e290]. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(8):2351-2371. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004050 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34132223/

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):674-688. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000121945.36635.61 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15064596/

Blanchard S, Glasgow P. A theoretical model to describe progressions and regressions for exercise rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2014;15(3):131-135. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.05.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24913914/

Liu CJ, Latham NK. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(3):CD002759. Published 2009 Jul 8. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4324332/

American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19204579/

Bell LR, McNicol AJ, McNeil E, Van Nguyen H, Hunter JR, O’Brien BJ. The impact of progressive overload on the proportion and frequency of positive cardio-respiratory fitness responders. J Sci Med Sport. 2023;26(10):561-563. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2023.08.175 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37643931/

Taylor NF, Dodd KJ, Damiano DL. Progressive resistance exercise in physical therapy: a summary of systematic reviews. Phys Ther. 2005;85(11):1208-1223. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16253049/

Hollings M, Mavros Y, Freeston J, Fiatarone Singh M. The effect of progressive resistance training on aerobic fitness and strength in adults with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(12):1242-1259. doi:10.1177/2047487317713329 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578612/

Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive endurance exercise training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):869-877. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2012.06.028 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23194487/

Plotkin D, Coleman M, Van Every D, et al. Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ. 2022;10:e14142. Published 2022 Sep 30. doi:10.7717/peerj.14142 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36199287/

McNicol AJ, O’Brien BJ, Paton CD, Knez WL. The effects of increased absolute training intensity on adaptations to endurance exercise training. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(4):485-489. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2008.03.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18762454/

Lorenz D, Morrison S. CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(6):734-747. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4637911/

Mann JB, Thyfault JP, Ivey PA, Sayers SP. The effect of autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise vs. linear periodization on strength improvement in college athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(7):1718-1723. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181def4a6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20543732/

Greig L, Stephens Hemingway BH, Aspe RR, Cooper K, Comfort P, Swinton PA. Autoregulation in Resistance Training: Addressing the Inconsistencies. Sports Med. 2020;50(11):1873-1887. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01330-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32813181/

Hartmann H, Wirth K, Keiner M, Mickel C, Sander A, Szilvas E. Short-term Periodization Models: Effects on Strength and Speed-strength Performance. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1373-1386. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0355-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26133514/

Kildow AR, Wright G, Reh RM, Jaime S, Doberstein S. Can Monitoring Training Load Deter Performance Drop-off During Off-season Training in Division III American Football Players?. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(7):1745-1754. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003149 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31145385/

González-Ravé JM, González-Mohino F, Rodrigo-Carranza V, Pyne DB. Reverse Periodization for Improving Sports Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):56. Published 2022 Apr 21. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00445-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35445953/

Moesgaard L, Beck MM, Christiansen L, Aagaard P, Lundbye-Jensen J. Effects of Periodization on Strength and Muscle Hypertrophy in Volume-Equated Resistance Training Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(7):1647-1666. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01636-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35044672/

Williams TD, Tolusso DV, Fedewa MV, Esco MR. Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(10):2083-2100. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0734-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28497285/

Miranda F, Simão R, Rhea M, et al. Effects of linear vs. daily undulatory periodized resistance training on maximal and submaximal strength gains. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(7):1824-1830. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e7ff75 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21499134/

Monteiro AG, Aoki MS, Evangelista AL, et al. Nonlinear periodization maximizes strength gains in split resistance training routines. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(4):1321-1326. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a00f96 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19528843/

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of linear and undulating periodized resistance training programs on muscular strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):1113-1125. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000712 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25268290/

De Souza EO, Tricoli V, Rauch J, et al. Different Patterns in Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations in Untrained Individuals Undergoing Nonperiodized and Periodized Strength Regimens. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1238-1244. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002482 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29683914/

Bartolomei S, Zaniboni F, Verzieri N, Hoffman JR. New Perspectives in Resistance Training Periodization: Mixed Session vs. Block Periodized Programs in Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2023;37(3):537-545. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004465 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36727999/

Bartolomei S, Hoffman JR, Merni F, Stout JR. A comparison of traditional and block periodized strength training programs in trained athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(4):990-997. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000366 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24476775/

Evans JW. Periodized Resistance Training for Enhancing Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength: A Mini-Review. Front Physiol. 2019;10:13. Published 2019 Jan 23. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00013 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30728780/

Fleck SJ. Non-linear periodization for general fitness & athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2011;29A:41-45. doi:10.2478/v10078-011-0057-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23486658/

Kiely J. Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: evidence-led or tradition-driven?. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7(3):242-250. doi:10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22356774/

Kiely J. Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):753-764. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0823-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29189930/

Mujika I, Halson S, Burke LM, Balagué G, Farrow D. An Integrated, Multifactorial Approach to Periodization for Optimal Performance in Individual and Team Sports. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(5):538-561. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0093 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29848161/

Issurin VB. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports Med. 2010;40(3):189-206. doi:10.2165/11319770-000000000-00000 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20199119/

Issurin V. Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(1):65-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18212712/

Issurin VB. Benefits and Limitations of Block Periodized Training Approaches to Athletes’ Preparation: A Review. Sports Med. 2016;46(3):329-338. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0425-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26573916/

Cunanan AJ, DeWeese BH, Wagle JP, et al. The General Adaptation Syndrome: A Foundation for the Concept of Periodization. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):787-797. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0855-3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29307100/

Buckner SL, Mouser JG, Dankel SJ, Jessee MB, Mattocks KT, Loenneke JP. The General Adaptation Syndrome: Potential misapplications to resistance exercise. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(11):1015-1017. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.02.012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28377133/

Fisher JP, Csapo R. Periodization and Programming in Sports. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(2):13. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.3390/sports9020013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7909405/

Larsen S, Kristiansen E, van den Tillaar R. Effects of subjective and objective autoregulation methods for intensity and volume on enhancing maximal strength during resistance-training interventions: a systematic review. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10663. Published 2021 Jan 12. doi:10.7717/peerj.10663 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33520457/

Hickmott LM, Chilibeck PD, Shaw KA, Butcher SJ. The Effect of Load and Volume Autoregulation on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):9. Published 2022 Jan 15. doi:10.1186/s40798-021-00404-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35038063/

Vann CG, Haun CT, Osburn SC, et al. Molecular Differences in Skeletal Muscle After 1 Week of Active vs. Passive Recovery From High-Volume Resistance Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(8):2102-2113. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004071 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34138821/

Alves RC, Prestes J, Enes A, et al. Training Programs Designed for Muscle Hypertrophy in Bodybuilders: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(11):149. Published 2020 Nov 18. doi:10.3390/sports8110149 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7698840/

Bell L, Nolan D, Immonen V, et al. “You can’t shoot another bullet until you’ve reloaded the gun”: Coaches’ perceptions, practices and experiences of deloading in strength and physique sports. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:1073223. Published 2022 Dec 21. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.1073223 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36619355/

Coleman M, Burke R, Augustin F, et al. Gaining more from doing less? The effects of a one-week deload period during supervised resistance training on muscular adaptations. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16777. Published 2024 Jan 22. doi:10.7717/peerj.16777 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38274324/

Bell L, Strafford BW, Coleman M, Androulakis Korakakis P, Nolan D. Integrating Deloading into Strength and Physique Sports Training Programmes: An International Delphi Consensus Approach. Sports Med Open. 2023;9(1):87. Published 2023 Sep 21. doi:10.1186/s40798-023-00633-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37730925/

Rogerson D, Nolan D, Korakakis PA, Immonen V, Wolf M, Bell L. Deloading Practices in Strength and Physique Sports: A Cross-sectional Survey. Sports Med Open. 2024;10(1):26. Published 2024 Mar 18. doi:10.1186/s40798-024-00691-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38499934/