If you haven’t already, then reading our articles on why exercise is so important, what the goals of exercise are, and the different types of exercise we have available to us, then it would be incredibly helpful to go back and read them now. If you need more tailored and personalised advice on how to structure your own training, then we may be able to help you via online coaching.

Exercise Guidelines

As you will remember from our article on the types of exercise, there is another type of exercise that hasn’t been mentioned here, which is organised sport/group training. This is difficult to create guidelines around, because it is actually an incredibly broad category. There is a big difference between doing something like rugby and doing yoga. However, doing this type of exercise can contribute significantly to your general activity levels, and potentially have effects that are similar to resistance training or cardio training. As such, if you intend to include this type of exercise, you will have to adjust the recommendations accordingly.

For example, if you are doing an intense grappling sport like wrestling, you may already be significantly taxing your muscles and cardiovascular system. As such, if you also want to include resistance training, you may need an even lower volume of work to see benefits, and you may also only be able to recover from a lower volume of resistance training. So the exercise guidelines for each type of exercise aren’t entirely additive, and you do have to take into account the entirety of your exercise habits.

Clear Goals

Exercise Guidelines Overview

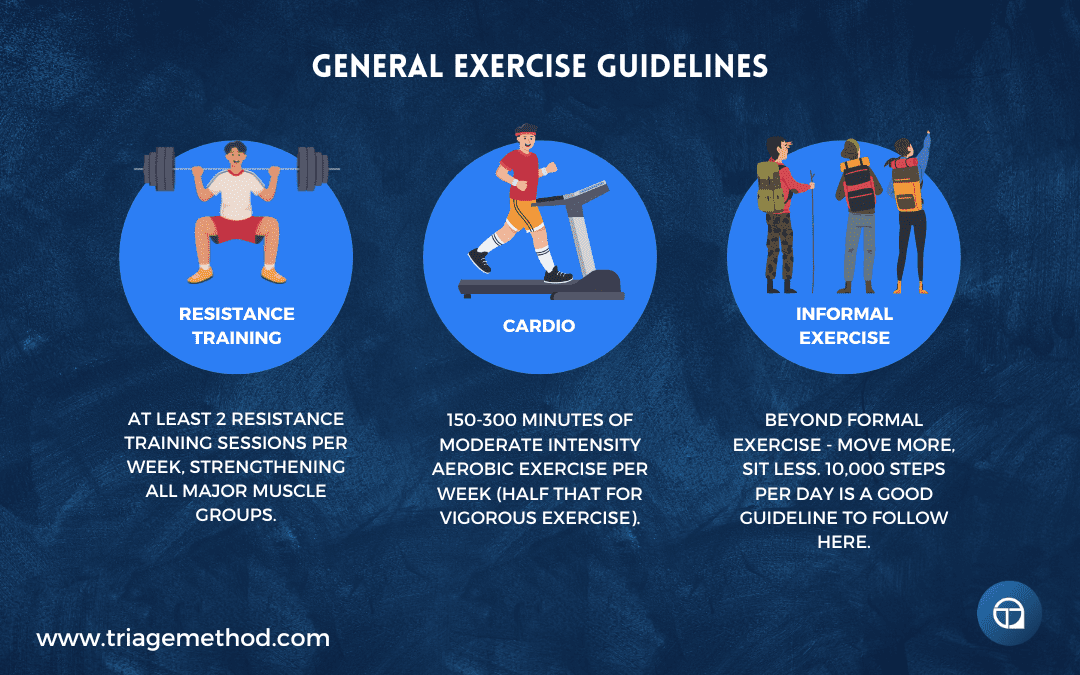

The general exercise guidelines are as follows:

These are good rough starting points, and can be thought of as the minimum exercise goal.

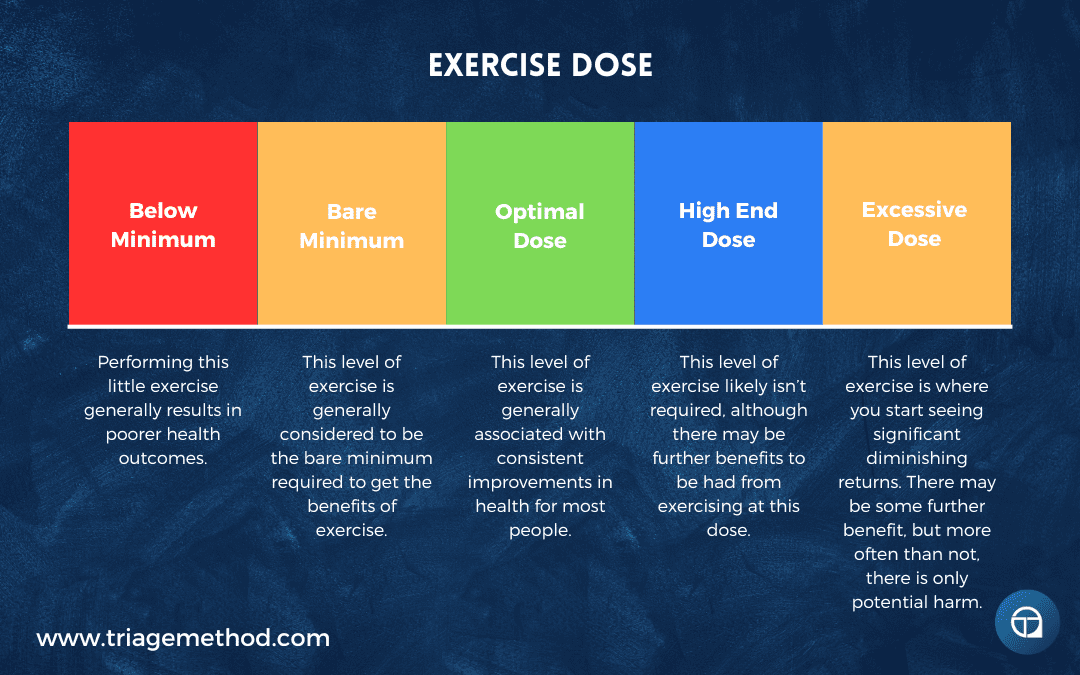

However, we can actually get a bit more specific with our recommendations. As such, the following guideline parameters seem to make sense for most people.

Staying somewhere between the lower limit and the upper limit will put you in a good place. However, depending on your specific goals, you may wish to do more or less of one of these exercise types.

References and Further Reading

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451-1462. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239350/

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020-2028. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14854 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30418471/

O’Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, et al. The ABC of Physical Activity for Health: a consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(6):573-591. doi:10.1080/02640411003671212 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20401789/

Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423-1434. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17762377/

Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in Adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for Aerobic Activity and Time Spent on Sedentary Behavior Among US Adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197597. Published 2019 Jul 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7597 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31348504/

Ding D, Mutrie N, Bauman A, Pratt M, Hallal PRC, Powell KE. Physical activity guidelines 2020: comprehensive and inclusive recommendations to activate populations. Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1780-1782. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32229-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33248019/

DiPietro L, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle SJH, et al. Advancing the global physical activity agenda: recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):143. Published 2020 Nov 26. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01042-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239105/

Burtscher J, Burtscher M. Run for your life: tweaking the weekly physical activity volume for longevity. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(13):759-760. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101350 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31630092/

Marin-Couture E, Pérusse L, Tremblay A. The fit-active profile to better reflect the benefits of a lifelong vigorous physical activity participation: mini-review of literature and population data. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(7):763-770. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-1109 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33667123/

O’Keefe JH, O’Keefe EL, Lavie CJ. The Goldilocks Zone for Exercise: Not Too Little, Not Too Much. Mo Med. 2018;115(2):98-105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6139866/

O’Keefe JH, O’Keefe EL, Eckert R, Lavie CJ. Training Strategies to Optimize Cardiovascular Durability and Life Expectancy. Mo Med. 2023;120(2):155-162. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10121111/

Lee DH, Rezende LFM, Joh HK, et al. Long-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US Adults. Circulation. 2022;146(7):523-534. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.058162 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9378548/

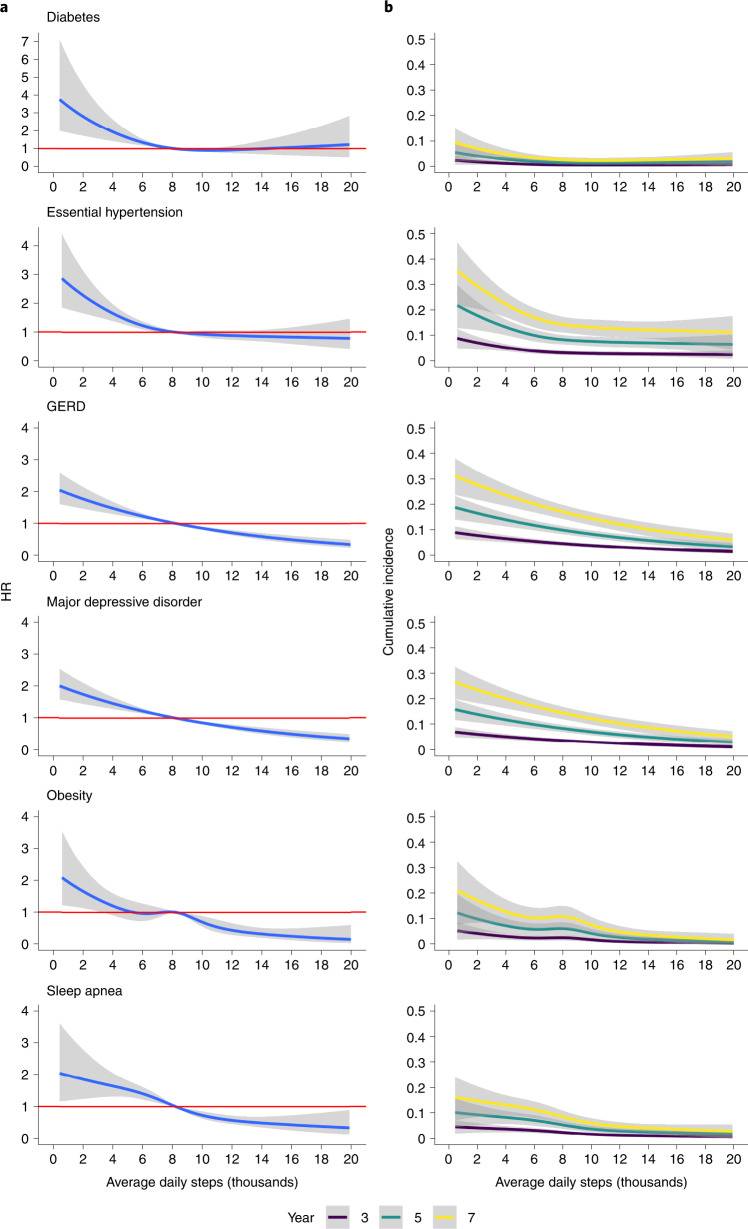

Master H, Annis J, Huang S, et al. Association of step counts over time with the risk of chronic disease in the All of Us Research Program [published correction appears in Nat Med. 2023 Dec;29(12):3270]. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2301-2308. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02012-w https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36216933/

Choi BC, Pak AW, Choi JC, Choi EC. Daily step goal of 10,000 steps: a literature review. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(3):E146-E151. doi:10.25011/cim.v30i3.1083 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17716553/

Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR Jr. How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Med. 2004;34(1):1-8. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434010-00001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14715035/

Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(3):e219-e228. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00302-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35247352/

Hall KS, Hyde ET, Bassett DR, et al. Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):78. Published 2020 Jun 20. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-00978-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7305604/

Yuenyongchaiwat K. Effects of 10,000 steps a day on physical and mental health in overweight participants in a community setting: a preliminary study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(4):367-373. doi:10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0160 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27556393/

Ahmadi MN, Rezende LFM, Ferrari G, Del Pozo Cruz B, Lee IM, Stamatakis E. Do the associations of daily steps with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease differ by sedentary time levels? A device-based cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2024;58(5):261-268. Published 2024 Mar 8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-107221 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38442950/

Castres I, Tourny C, Lemaitre F, Coquart J. Impact of a walking program of 10,000 steps per day and dietary counseling on health-related quality of life, energy expenditure and anthropometric parameters in obese subjects. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(2):135-141. doi:10.1007/s40618-016-0530-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27600387/

Morgan AL, Tobar DA, Snyder L. Walking toward a new me: the impact of prescribed walking 10,000 steps/day on physical and psychological well-being. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(3):299-307. doi:10.1123/jpah.7.3.299 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20551485/

Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojdała G, Gołaś A. Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):4897. Published 2019 Dec 4. doi:10.3390/ijerph16244897 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950543/

Chen HT, Chung YC, Chen YJ, Ho SY, Wu HJ. Effects of Different Types of Exercise on Body Composition, Muscle Strength, and IGF-1 in the Elderly with Sarcopenic Obesity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(4):827-832. doi:10.1111/jgs.14722 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28205203/

van Baak MA, Pramono A, Battista F, et al. Effect of different types of regular exercise on physical fitness in adults with overweight or obesity: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Obes Rev. 2021;22 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):e13239. doi:10.1111/obr.13239 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33939229/

Plotkin DL, Roberts MD, Haun CT, Schoenfeld BJ. Muscle Fiber Type Transitions with Exercise Training: Shifting Perspectives. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(9):127. Published 2021 Sep 10. doi:10.3390/sports9090127 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8473039/

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Van Every DW, Plotkin DL. Loading Recommendations for Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Local Endurance: A Re-Examination of the Repetition Continuum. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(2):32. Published 2021 Feb 22. doi:10.3390/sports9020032 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7927075/

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Buchan D, Baker JS. Weekly Training Frequency Effects on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):36. Published 2018 Aug 3. doi:10.1186/s40798-018-0149-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30076500/

Behm DG, Young JD, Whitten JHD, et al. Effectiveness of Traditional Strength vs. Power Training on Muscle Strength, Power and Speed with Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:423. Published 2017 Jun 30. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00423 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5491841/

Maestroni L, Read P, Bishop C, et al. The Benefits of Strength Training on Musculoskeletal System Health: Practical Applications for Interdisciplinary Care. Sports Med. 2020;50(8):1431-1450. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01309-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32564299/

Folland JP, Williams AG. The adaptations to strength training : morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports Med. 2007;37(2):145-168. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17241104/

Iversen VM, Norum M, Schoenfeld BJ, Fimland MS. No Time to Lift? Designing Time-Efficient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2079-2095. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01490-1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8449772/

Calatayud J, Vinstrup J, Jakobsen MD, et al. Importance of mind-muscle connection during progressive resistance training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(3):527-533. doi:10.1007/s00421-015-3305-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26700744/

Colquhoun RJ, Gai CM, Aguilar D, et al. Training Volume, Not Frequency, Indicative of Maximal Strength Adaptations to Resistance Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1207-1213. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002414 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29324578/

Thomas MH, Burns SP. Increasing Lean Mass and Strength: A Comparison of High Frequency Strength Training to Lower Frequency Strength Training. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016;9(2):159-167. Published 2016 Apr 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4836564/

Schumann M, Feuerbacher JF, Sünkeler M, et al. Compatibility of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training for Skeletal Muscle Size and Function: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(3):601-612. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01587-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34757594/

de Santana DA, Castro A, Cavaglieri CR. Strength Training Volume to Increase Muscle Mass Responsiveness in Older Individuals: Weekly Sets Based Approach. Front Physiol. 2021;12:759677. Published 2021 Sep 30. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.759677 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8514686/

Balshaw TG, Maden-Wilkinson TM, Massey GJ, Folland JP. The Human Muscle Size and Strength Relationship: Effects of Architecture, Muscle Force, and Measurement Location. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(10):2140-2151. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002691 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33935234/

Bernárdez-Vázquez R, Raya-González J, Castillo D, Beato M. Resistance Training Variables for Optimization of Muscle Hypertrophy: An Umbrella Review. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:949021. Published 2022 Jul 4. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.949021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9302196/

Heidel KA, Novak ZJ, Dankel SJ. Machines and free weight exercises: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing changes in muscle size, strength, and power. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2022;62(8):1061-1070. doi:10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12929-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34609100/

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Baker JS. The Effect of Weekly Set Volume on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(12):2585-2601. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0762-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28755103/

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Hornsby WG, Stone MH. Training for Muscular Strength: Methods for Monitoring and Adjusting Training Intensity. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2051-2066. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01488-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34101157/

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Michalopoulos N, Fisher JP, et al. The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required for 1RM Strength in Powerlifters. Front Sports Act Living. 2021;3:713655. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.3389/fspor.2021.713655 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34527944/

Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857-2872. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20847704/

Baz-Valle E, Balsalobre-Fernández C, Alix-Fages C, Santos-Concejero J. A Systematic Review of The Effects of Different Resistance Training Volumes on Muscle Hypertrophy. J Hum Kinet. 2022;81:199-210. Published 2022 Feb 10. doi:10.2478/hukin-2022-0017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8884877/

Beattie K, Kenny IC, Lyons M, Carson BP. The effect of strength training on performance in endurance athletes. Sports Med. 2014;44(6):845-865. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0157-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24532151/

Hottenrott K, Ludyga S, Schulze S. Effects of high intensity training and continuous endurance training on aerobic capacity and body composition in recreationally active runners. J Sports Sci Med. 2012;11(3):483-488. Published 2012 Sep 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3737930/

Jamka M, Mądry E, Krzyżanowska-Jankowska P, et al. The effect of endurance and endurance-strength training on body composition and cardiometabolic markers in abdominally obese women: a randomised trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12339. Published 2021 Jun 11. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90526-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34117276/

Doma K, Deakin GB, Schumann M, Bentley DJ. Training Considerations for Optimising Endurance Development: An Alternate Concurrent Training Perspective. Sports Med. 2019;49(5):669-682. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01072-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30847824/

Düking P, Zinner C, Trabelsi K, et al. Monitoring and adapting endurance training on the basis of heart rate variability monitored by wearable technologies: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(11):1180-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2021.04.012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34489178/

Milanović Z, Sporiš G, Weston M. Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) and Continuous Endurance Training for VO2max Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1469-1481. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26243014/

Herzig D, Asatryan B, Brugger N, Eser P, Wilhelm M. The Association Between Endurance Training and Heart Rate Variability: The Confounding Role of Heart Rate. Front Physiol. 2018;9:756. Published 2018 Jun 19. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00756 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29971016/

Laursen PB, Shing CM, Peake JM, Coombes JS, Jenkins DG. Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(11):1801-1807. doi:10.1097/00005768-200211000-00017 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12439086/

Cadore EL, Pinto RS, Bottaro M, Izquierdo M. Strength and endurance training prescription in healthy and frail elderly. Aging Dis. 2014;5(3):183-195. Published 2014 Jun 1. doi:10.14336/AD.2014.0500183 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4037310/

Baquet G, van Praagh E, Berthoin S. Endurance training and aerobic fitness in young people. Sports Med. 2003;33(15):1127-1143. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333150-00004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14719981/

Vesterinen V, Nummela A, Heikura I, et al. Individual Endurance Training Prescription with Heart Rate Variability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(7):1347-1354. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000910 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26909534/

Wilson JM, Marin PJ, Rhea MR, Wilson SM, Loenneke JP, Anderson JC. Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2293-2307. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22002517/

Tanaka H, Swensen T. Impact of resistance training on endurance performance. A new form of cross-training?. Sports Med. 1998;25(3):191-200. doi:10.2165/00007256-199825030-00005 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9554029/

Foster C, Farland CV, Guidotti F, et al. The Effects of High Intensity Interval Training vs Steady State Training on Aerobic and Anaerobic Capacity. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(4):747-755. Published 2015 Nov 24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4657417/

Stöggl TL, Sperlich B. The training intensity distribution among well-trained and elite endurance athletes. Front Physiol. 2015;6:295. Published 2015 Oct 27. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00295 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4621419/

Gaesser GA, Angadi SS. High-intensity interval training for health and fitness: can less be more?. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;111(6):1540-1541. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01237.2011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21979806/

Methenitis S. A Brief Review on Concurrent Training: From Laboratory to the Field. Sports (Basel). 2018;6(4):127. Published 2018 Oct 24. doi:10.3390/sports6040127 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6315763/

Berryman N, Mujika I, Bosquet L. Concurrent Training for Sports Performance: The 2 Sides of the Medal. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019;14(3):279-285. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0103 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29809072/

Baar K. Using molecular biology to maximize concurrent training. Sports Med. 2014;44 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S117-S125. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0252-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25355186/

Sousa AC, Neiva HP, Gil MH, et al. Concurrent Training and Detraining: The Influence of Different Aerobic Intensities. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(9):2565-2574. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002874 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30946274/

Gäbler M, Prieske O, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. The Effects of Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training on Physical Fitness and Athletic Performance in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1057. Published 2018 Aug 7. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01057 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30131714/

Leveritt M, Abernethy PJ, Barry BK, Logan PA. Concurrent strength and endurance training. A review. Sports Med. 1999;28(6):413-427. doi:10.2165/00007256-199928060-00004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10623984/

Huiberts RO, Wüst RCI, van der Zwaard S. Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Sex and Training Status. Sports Med. 2024;54(2):485-503. doi:10.1007/s40279-023-01943-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37847373/

Scribbans TD, Vecsey S, Hankinson PB, Foster WS, Gurd BJ. The Effect of Training Intensity on VO2max in Young Healthy Adults: A Meta-Regression and Meta-Analysis. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016;9(2):230-247. Published 2016 Apr 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4836566/

Gim MN, Choi JH. The effects of weekly exercise time on VO2max and resting metabolic rate in normal adults. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(4):1359-1363. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.1359 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4868243/

Gormley SE, Swain DP, High R, et al. Effect of intensity of aerobic training on VO2max. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7):1336-1343. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816c4839 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18580415/

Paddy Farrell

Hey, I'm Paddy!

I am a coach who loves to help people master their health and fitness. I am a personal trainer, strength and conditioning coach, and I have a degree in Biochemistry and Biomolecular Science. I have been coaching people for over 10 years now.

When I grew up, you couldn't find great health and fitness information, and you still can't really. So my content aims to solve that!

I enjoy training in the gym, doing martial arts and hiking in the mountains (around Europe, mainly). I am also an avid reader of history, politics and science. When I am not in the mountains, exercising or reading, you will likely find me in a museum.