However, to use these tools effectively, you have to understand what your goals are and what the goals of exercise are. We spend a lot of time at the start of the coaching process really nailing down goals with our clients, as this allows us to be much more specific in what type of exercise we are going to use to achieve those goals. So, if you want to use the information in this article to create a better exercise program for yourself, then we would recommend that you spend some time getting clear on what your specific goals are. This will allow you to better understand which type of exercise will be more appropriate for your goals.

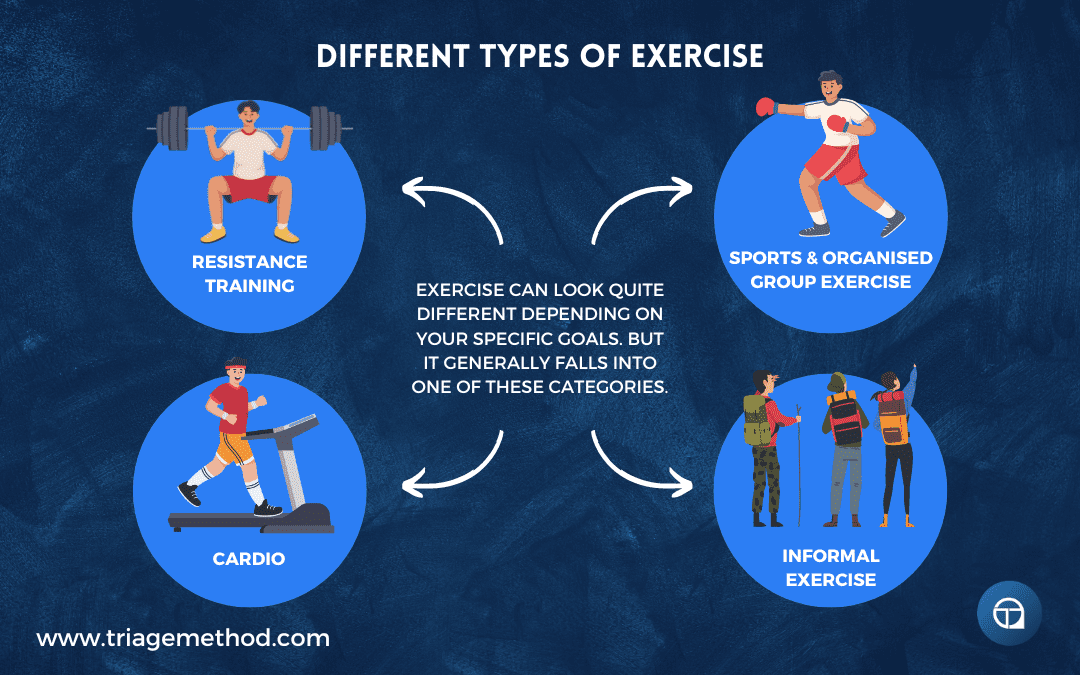

The Four Types Of Exercise

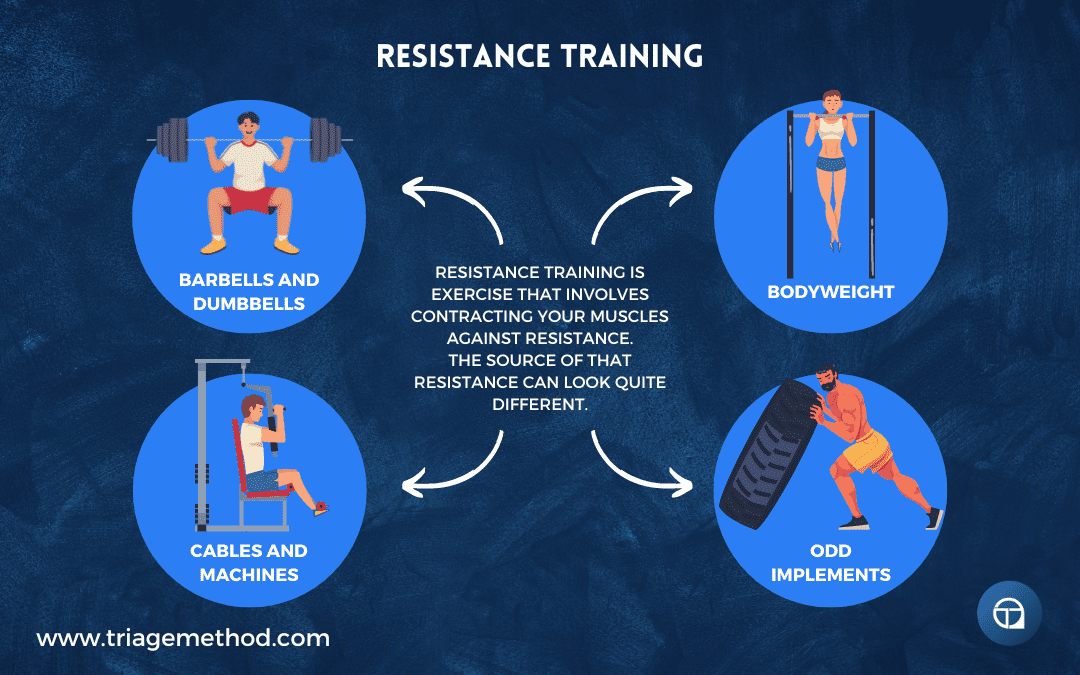

Resistance Training

Resistance Training Adaptations

Cardiovascular Training

Cardiovascular Training Adaptations and Tradeoffs

Sports/Organised Group Training

Organised Sports/Group Training Adaptations

Informal Exercise

The Types Of Exercise As Tools In Your Toolbox

References and Further Reading

Ruegsegger GN, Booth FW. Health Benefits of Exercise. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(7):a029694. Published 2018 Jul 2. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a029694 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6027933/

Posadzki P, Pieper D, Bajpai R, et al. Exercise/physical activity and health outcomes: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1724. Published 2020 Nov 16. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09855-3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33198717/

Warburton DER, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017;32(5):541-556. doi:10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28708630/

Kramer A. An Overview of the Beneficial Effects of Exercise on Health and Performance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1228:3-22. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32342447/

Qiu Y, Fernández-García B, Lehmann HI, et al. Exercise sustains the hallmarks of health. J Sport Health Sci. 2023;12(1):8-35. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.10.003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9923435/

Thompson WR, Sallis R, Joy E, Jaworski CA, Stuhr RM, Trilk JL. Exercise Is Medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(5):511-523. Published 2020 Apr 22. doi:10.1177/1559827620912192 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7444006/

Chen, YT., Fredericson, M., Matheson, G. et al. Exercise is Medicine. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 1, 48–56 (2013). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40141-013-0006-1

Sallis RE. Exercise is medicine and physicians need to prescribe it!. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):3-4. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.054825 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18971243/

Sallis R. Exercise is medicine: a call to action for physicians to assess and prescribe exercise. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43(1):22-26. doi:10.1080/00913847.2015.1001938 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25684558/

Li J, Qiu H, Li J. Exercise is medicine. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1129221. Published 2023 Jan 30. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2023.1129221 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9922893/

Langan SP, Grosicki GJ. Exercise Is Medicine…and the Dose Matters. Front Physiol. 2021;12:660818. Published 2021 May 12. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.660818 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34054576/

Anderson E, Durstine JL. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Med Health Sci. 2019;1(1):3-10. Published 2019 Sep 10. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2019.08.006 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9219321/

Hamer M, Endrighi R, Poole L. Physical activity, stress reduction, and mood: insight into immunological mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;934:89-102. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-071-7_5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22933142/

El-Kotob R, Ponzano M, Chaput JP, et al. Resistance training and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45(10 (Suppl. 2)):S165-S179. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-0245 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33054335/

Shailendra P, Baldock KL, Li LSK, Bennie JA, Boyle T. Resistance Training and Mortality Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(2):277-285. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2022.03.020 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35599175/

Paluch AE, Boyer WR, Franklin BA, et al. Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(3):e217-e231. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001189 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38059362/

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA, French DN. Resistance training for health and performance. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(3):165-171. doi:10.1249/00149619-200206000-00007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12831709/

Strasser B, Volaklis K, Fuchs D, Burtscher M. Role of Dietary Protein and Muscular Fitness on Longevity and Aging. Aging Dis. 2018;9(1):119-132. Published 2018 Feb 1. doi:10.14336/AD.2017.0202 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5772850/

McLeod M, Breen L, Hamilton DL, Philp A. Live strong and prosper: the importance of skeletal muscle strength for healthy ageing. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):497-510. doi:10.1007/s10522-015-9631-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4889643/

Witard OC, McGlory C, Hamilton DL, Phillips SM. Growing older with health and vitality: a nexus of physical activity, exercise and nutrition. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):529-546. doi:10.1007/s10522-016-9637-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26878863/

Chen L, Nelson DR, Zhao Y, Cui Z, Johnston JA. Relationship between muscle mass and muscle strength, and the impact of comorbidities: a population-based, cross-sectional study of older adults in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:74. Published 2013 Jul 16. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-13-74 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3765109/

Srikanthan P, Karlamangla AS. Muscle mass index as a predictor of longevity in older adults. Am J Med. 2014;127(6):547-553. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24561114/

Moghetti P, Bacchi E, Brangani C, Donà S, Negri C. Metabolic Effects of Exercise. Front Horm Res. 2016;47:44-57. doi:10.1159/000445156 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27348753/

Hong AR, Kim SW. Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2018;33(4):435-444. doi:10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.435 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6279907/

Manaye S, Cheran K, Murthy C, et al. The Role of High-intensity and High-impact Exercises in Improving Bone Health in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e34644. Published 2023 Feb 5. doi:10.7759/cureus.34644 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9990535/

Liu Y, Lee DC, Li Y, et al. Associations of Resistance Exercise with Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity and Mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(3):499-508. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001822 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7385554/

Lee DC, Brellenthin AG, Lanningham-Foster LM, Kohut ML, Li Y. Aerobic, resistance, or combined exercise training and cardiovascular risk profile in overweight or obese adults: the CardioRACE trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(13):1127-1142. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad827 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38233024/

Halle M, Papadakis M. A new dawn of managing cardiovascular risk in obesity: the importance of combining lifestyle intervention and medication. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(13):1143-1145. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae091 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38366823/

Kirkman DL, Lee DC, Carbone S. Resistance exercise for cardiac rehabilitation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;70:66-72. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2022.01.004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8930531/

Westcott WL. Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):209-216. doi:10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825dabb8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22777332/

Lavie CJ, Lee DC, Sui X, et al. Effects of Running on Chronic Diseases and Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(11):1541-1552. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26362561/

Hackett DA. Lung Function and Respiratory Muscle Adaptations of Endurance- and Strength-Trained Males. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(12):160. Published 2020 Dec 10. doi:10.3390/sports8120160 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7764033/

Hellsten Y, Nyberg M. Cardiovascular Adaptations to Exercise Training. Compr Physiol. 2015;6(1):1-32. Published 2015 Dec 15. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140080 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26756625/

Lässing J, Maudrich T, Kenville R, et al. Intensity-dependent cardiopulmonary response during and after strength training. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6632. Published 2023 Apr 24. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33873-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37095279/

Benck LR, Cuttica MJ, Colangelo LA, et al. Association between Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Lung Health from Young Adulthood to Middle Age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1236-1243. doi:10.1164/rccm.201610-2089OC https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5439017/

Reimers AK, Knapp G, Reimers CD. Effects of Exercise on the Resting Heart Rate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12):503. Published 2018 Dec 1. doi:10.3390/jcm7120503 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6306777/

Gielen S, Schuler G, Adams V. Cardiovascular effects of exercise training: molecular mechanisms. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1221-1238. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.939959 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20855669/

Muscella A, Stefàno E, Marsigliante S. The effects of exercise training on lipid metabolism and coronary heart disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319(1):H76-H88. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2019 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32442027/

Wilson MG, Ellison GM, Cable NT. Basic science behind the cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Heart. 2015;101(10):758-765. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306596 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25911667/

Franklin BA, Eijsvogels TMH, Pandey A, Quindry J, Toth PP. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and cardiovascular health: A clinical practice statement of the ASPC Part I: Bioenergetics, contemporary physical activity recommendations, benefits, risks, extreme exercise regimens, potential maladaptations. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;12:100424. Published 2022 Oct 13. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100424 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36281324/

Rao P, Belanger MJ, Robbins JM. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Cardiometabolic Health: Insights into the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiometabolic Diseases. Cardiol Rev. 2022;30(4):167-178. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000416 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8920940/

Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and the Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1652. Published 2019 Jul 19. doi:10.3390/nu11071652 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6683051/

Giallauria F, Strisciuglio T, Cuomo G, et al. Exercise Training: The Holistic Approach in Cardiovascular Prevention. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2021;28(6):561-577. doi:10.1007/s40292-021-00482-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8590648/

Franklin BA, Wedig IJ, Sallis RE, Lavie CJ, Elmer SJ. Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness as Modulators of Health Outcomes: A Compelling Research-Based Case Presented to the Medical Community. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98(2):316-331. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36737120/

Reimers CD, Knapp G, Reimers AK. Does physical activity increase life expectancy? A review of the literature. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:243958. doi:10.1155/2012/243958 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3395188/

Santos AC, Willumsen J, Meheus F, Ilbawi A, Bull FC. The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to public health-care systems: a population-attributable fraction analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(1):e32-e39. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00464-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36480931/

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219-229. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22818936/

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants [published correction appears in Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Jan;7(1):e36]. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077-e1086. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30193830/

Duggal NA, Niemiro G, Harridge SDR, Simpson RJ, Lord JM. Can physical activity ameliorate immunosenescence and thereby reduce age-related multi-morbidity?. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(9):563-572. doi:10.1038/s41577-019-0177-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31175337/

Nusselder WJ, Franco OH, Peeters A, Mackenbach JP. Living healthier for longer: comparative effects of three heart-healthy behaviors on life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:487. Published 2009 Dec 24. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-487 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2813239/

Gremeaux V, Gayda M, Lepers R, Sosner P, Juneau M, Nigam A. Exercise and longevity. Maturitas. 2012;73(4):312-317. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.09.012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23063021/

Wen CP, Wai JP, Tsai MK, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378(9798):1244-1253. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60749-6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21846575/

Kopp M, Burtscher M. Aiming at Optimal Physical Activity for Longevity (OPAL). Sports Med Open. 2021;7(1):70. Published 2021 Oct 9. doi:10.1186/s40798-021-00360-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8502188/

Lee IM, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hennekens CH. Physical activity, physical fitness and longevity. Aging (Milano). 1997;9(1-2):2-11. doi:10.1007/BF03340123 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9177581/

Sheehan CM, Li L. Associations of Exercise Types with All-Cause Mortality among U.S. Adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(12):2554-2562. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002406 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32520868/

Lear SA, Hu W, Rangarajan S, et al. The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: the PURE study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Dec 16;390(10113):2626]. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2643-2654. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31634-3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28943267/

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451-1462. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239350/

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020-2028. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14854 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30418471/

O’Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, et al. The ABC of Physical Activity for Health: a consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(6):573-591. doi:10.1080/02640411003671212 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20401789/

Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423-1434. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17762377/

Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in Adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for Aerobic Activity and Time Spent on Sedentary Behavior Among US Adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197597. Published 2019 Jul 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7597 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31348504/

Ding D, Mutrie N, Bauman A, Pratt M, Hallal PRC, Powell KE. Physical activity guidelines 2020: comprehensive and inclusive recommendations to activate populations. Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1780-1782. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32229-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33248019/

DiPietro L, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle SJH, et al. Advancing the global physical activity agenda: recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):143. Published 2020 Nov 26. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01042-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239105/

Burtscher J, Burtscher M. Run for your life: tweaking the weekly physical activity volume for longevity. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(13):759-760. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101350 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31630092/

Marin-Couture E, Pérusse L, Tremblay A. The fit-active profile to better reflect the benefits of a lifelong vigorous physical activity participation: mini-review of literature and population data. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(7):763-770. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-1109 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33667123/

O’Keefe JH, O’Keefe EL, Lavie CJ. The Goldilocks Zone for Exercise: Not Too Little, Not Too Much. Mo Med. 2018;115(2):98-105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6139866/

O’Keefe JH, O’Keefe EL, Eckert R, Lavie CJ. Training Strategies to Optimize Cardiovascular Durability and Life Expectancy. Mo Med. 2023;120(2):155-162. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10121111/

Lee DH, Rezende LFM, Joh HK, et al. Long-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US Adults. Circulation. 2022;146(7):523-534. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.058162 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9378548/

Master H, Annis J, Huang S, et al. Association of step counts over time with the risk of chronic disease in the All of Us Research Program [published correction appears in Nat Med. 2023 Dec;29(12):3270]. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2301-2308. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02012-w https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36216933/

Choi BC, Pak AW, Choi JC, Choi EC. Daily step goal of 10,000 steps: a literature review. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(3):E146-E151. doi:10.25011/cim.v30i3.1083 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17716553/

Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR Jr. How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Med. 2004;34(1):1-8. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434010-00001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14715035/

Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(3):e219-e228. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00302-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35247352/

Hall KS, Hyde ET, Bassett DR, et al. Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):78. Published 2020 Jun 20. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-00978-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7305604/

Yuenyongchaiwat K. Effects of 10,000 steps a day on physical and mental health in overweight participants in a community setting: a preliminary study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(4):367-373. doi:10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0160 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27556393/

Ahmadi MN, Rezende LFM, Ferrari G, Del Pozo Cruz B, Lee IM, Stamatakis E. Do the associations of daily steps with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease differ by sedentary time levels? A device-based cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2024;58(5):261-268. Published 2024 Mar 8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-107221 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38442950/

Castres I, Tourny C, Lemaitre F, Coquart J. Impact of a walking program of 10,000 steps per day and dietary counseling on health-related quality of life, energy expenditure and anthropometric parameters in obese subjects. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(2):135-141. doi:10.1007/s40618-016-0530-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27600387/

Morgan AL, Tobar DA, Snyder L. Walking toward a new me: the impact of prescribed walking 10,000 steps/day on physical and psychological well-being. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(3):299-307. doi:10.1123/jpah.7.3.299 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20551485/

Paddy Farrell

Hey, I'm Paddy!

I am a coach who loves to help people master their health and fitness. I am a personal trainer, strength and conditioning coach, and I have a degree in Biochemistry and Biomolecular Science. I have been coaching people for over 10 years now.

When I grew up, you couldn't find great health and fitness information, and you still can't really. So my content aims to solve that!

I enjoy training in the gym, doing martial arts and hiking in the mountains (around Europe, mainly). I am also an avid reader of history, politics and science. When I am not in the mountains, exercising or reading, you will likely find me in a museum.