This health priority quiz was born out of the countless questions we get about various health hacks, supplements and novel interventions. Everyone is always searching for the next big thing, or the new secret hack. Every week it’s a new supplement, a trendy diet, a new exercise, a piece of equipment they saw on Instagram, and on and on. But the truth is, the things that really move the needle for your health and lifespan aren’t flashy. They’re the big, everyday habits that compound over decades.

The purpose of this health priority quiz is simply to show you how your lifestyle habits and health markers translate into real years of life gained, or lost, and to help you identify your highest priorities.

Instead of chasing distractions, you’ll know exactly which area deserves your attention first.

Now, one important caveat to this health priority quiz is that the numbers you’ll see here come from large, population-level studies. They’re averages. That means they don’t guarantee what you personally will experience, because genetics, medical history, and chance all play a role. But these studies give us a very reliable map of what tends to add or subtract years of life across thousands, sometimes millions, of people. Even if the exact numbers aren’t correct or don’t apply to you, directionally, they are correct. So, if we can stack the odds in our favour, why wouldn’t we?

Unfortunately, in my years of coaching, I’ve seen so many people pour their energy into the wrong details. They’ll worry about whether they should be drinking alkaline water or if collagen powder is “worth it,” but at the same time, they’re sleeping five hours a night, barely exercising, or eating fast food five times a week. People very regularly “step over dollars to pick up pennies”.

But I know it is difficult to know what to do. The reality is that not all health habits carry the same weight. Some have a massive effect on healthspan (how well you live) and lifespan (how long you live). Others matter, but only after you’ve nailed the basics. So, this quiz is designed to help you sort through the noise. It will highlight the major levers you should focus on. These are the things that research consistently shows have the biggest impact on how long and how well people live.

The health priority quiz doesn’t just tell you if you’re doing “well” or “poorly” in a general sense. It gives you a personalised priority list and helps identify the first place you should focus your efforts. That way, you stop wasting time on the little things and start getting the biggest return on your investment in health. This certainly isn’t medical advice, and there is only so much we can do without the extensive context we would normally get when coaching someone. But this quiz can be incredibly helpful for those of you who don’t have a coach in your corner.

Health Prioritisation Quiz

Complete the whole quiz. We’ll show every pass/fail and flag your first fail as the priority.

The Health Priority Quiz Big Picture

It seems to be the case that stacking multiple healthy habits together can add 10-14+ years of life. Unfortunately, the opposite is also true. If you ignore the fundamentals, the years slip away faster than most people realise.

Now, not all habits are equal. Some have a huge effect on your healthspan and lifespan. Others are still important, but the payoff is smaller. The smartest strategy is to start with the “big rocks” and then build from there. That is why the health priority quiz is organised the way it is. It works you through a list of the big rocks, and helps you identify which of these needs work. However, it is not only based on the science, it is also based on our extensive coaching experience, and how prioritising certain things can actually lead to better overall habits and results.

Anyway, the health priority quiz largely speaks for itself, but here’s a snapshot of what the science says about different lifestyle factors and how many years they typically add (or take away). Remember that these numbers come from population studies, so they represent averages, not personal guarantees. But they give us a powerful map of where the biggest returns on effort are.

Lifestyle & Health Outcomes Years of Life Lost or Gained

| Factor | Approx. Years of Life Lost or Gained |

| 🚬 Smoking | −10 yrs (quit at 35 regains 7-8 yrs; quit at 65 still +2 yrs) |

| 🍷 Alcohol | Heavy drinking: -2 to -5 yrs; Moderate/light: ~neutral to +1 yr |

| 🏃 Aerobic exercise | +3-4 yrs (up to +6-7 yrs in top performers) |

| 🏋 Resistance training | 10-17% ↓ mortality (+1-2 yrs) |

| 🫁 VO₂ max (top 25% vs bottom) | +5 yrs |

| ❤️ Resting heart rate (<60 vs >90 bpm) | +9 yrs |

| 💪 Strength | +2-5 yrs (weakest quartile = 50-67% ↑ mortality risk) |

| 🍎 Diet quality (Mediterranean / whole foods) | +9-11 yrs |

| 🥦 Fruit & veg ≥5/day | +2-3 yrs |

| 🌾 Fibre ≥10 g/1000 kcal | +1-2 yrs (each +10 g/day = 10% ↓ mortality) |

| 🥤 Sugary drinks (daily vs rare/none) | −2 yrs (20% ↑ premature mortality) |

| 🥩 Saturated fat (<10% of calories) | ~1-2 yrs (mainly via CVD risk) |

| 🛌 Sleep (7-9 hrs) | +2-4 yrs vs short sleepers |

| 🧘 Stress management | +2 yrs (chronic stress = 30-40% ↑ mortality risk) |

| 👥 Social connection | +5-7 yrs (isolation raises mortality risk ~26-29%) |

| ⚖️ BMI (healthy vs obese ≥35) | −3 to −10 yrs (dose-dependent) |

| 🧍 Body fat % (normal vs high) | −2-5 yrs |

| 📏 Waist circumference (>102 cm men / >88 cm women) | −3-5 yrs (independent of BMI) |

| 🧪 LDL cholesterol (<2.5 mmol/L vs high) | ~2-3 yrs (per +1 mmol/L ↑ LDL = +20% vascular events) |

There is a lot more individual context, and I certainly wouldn’t consider this to be the full story, but this health priority quiz is not meant to replace quality individualised coaching or medical advice.

Now, I know that some of you may be interested in hearing more about the various factors, and I want to go through a few key points with each of them. So, let’s dig in.

Smoking

If there’s one factor that overshadows all the rest when it comes to shortening your life, it’s smoking. Nothing else seems to come close. On average, being a lifelong smoker cuts about 10 years off your life. That’s a full decade just gone.

Luckily for those of you who do smoke, quitting makes a huge difference in your lifespan, even if you’ve been smoking for decades. And, the earlier you quit, the more years you gain back.

- Quit around age 35 → you can recover 7-8 years of life expectancy.

- Quit at 50 → you still regain about 6 years.

- Even quitting as late as 65 adds 2-3 years compared to continuing.

So when someone says, “It’s too late for me, the damage is already done,” that simply isn’t true. Every year without cigarettes is a year you’re giving your body a chance to repair. Your heart, lungs, and blood vessels all start healing within weeks and months of quitting.

From a coaching perspective, this is what I call the highest-return action you can take for your healthspan and lifespan. Yes, exercise, diet, sleep, stress management, and social connection all matter, but smoking is the single biggest negative lever. Quitting moves you from the “red zone” of high risk back toward neutral faster than anything else.

Regardless of whether you want to squeeze every year out of your lifespan, at the very least, you should try not to do things that actively reduce your lifespan. Quitting, or ideally never starting, smoking is just smart.

Priority Action: Quit Smoking

So, if you smoke, this is your number one priority. Before you think about supplements, superfoods, or advanced training programs, make a plan to stop.

Fortunately, you don’t have to do it alone. There are proven tools that dramatically improve your chances of success. These days, there are many tools you can use, such as nicotine replacement therapies, prescription medications, behavioural coaching, and support groups. The people who combine these approaches often have double or triple the quit rates compared to those who try to go cold turkey.

If you’re reading this and you smoke, look, I’m not here to judge you, I’m just here to remind you that quitting is the single most powerful step you can take to add years back to your life. If you’ve already quit? Congratulations, you’ve already made one of the biggest investments possible in your future health.

Alcohol

Alcohol is one of those tricky topics because it’s so socially embedded. For many people, a glass of wine or a beer is part of their routine, their social life, and even their identity. But when we look past the cultural lens and focus strictly on health outcomes, the reality is very clear that heavy drinking shortens life by about 2-5 years.

The risk rises with dose. More than 3 units per day (that’s around 21 units per week) consistently raises the likelihood of liver disease, certain cancers, high blood pressure, and early death. Unfortunately, those risks accumulate silently over time. You may not notice the impact at 30 or 40, but by 50, 60, or 70, the bill almost always comes due.

Now, you may be wondering, “but, what about “moderate” drinking?” Most guidelines define that as no more than 14 units per week for men and 7 for women, and ideally spread out, not binge-style (so, no more drinking 10 cans in a field on the weekend or finishing off a bottle of wine each night). Staying within those limits tends to be “near neutral” in terms of lifespan. In other words, you’re not losing much, but you’re not really gaining much either.

And the truth is, the best option for health is no alcohol at all. Studies that used to suggest a benefit from light drinking (like a glass of red wine) often failed to account for other factors, like the fact that light drinkers also tended to have healthier diets, better incomes, and more social support. Once researchers controlled for those, the protective effect of alcohol largely disappeared.

Priority Action: Reduce Heavy Drinking

If you’re drinking heavily, cutting down is one of the biggest wins you can make for your health and longevity. Even moving from heavy use down to guideline levels makes a measurable difference. If you can cut alcohol out altogether or make it an occasional indulgence rather than a routine habit, your long-term health will thank you.

In my coaching practice, I’ll ask clients: “Is alcohol adding more to your life than it’s taking away?” If the answer is not a very emphatic and measurable yes, then we have a clear next step. Sometimes that means switching to alcohol-free alternatives, limiting drinking to special occasions, or finding new social rituals that don’t revolve around a glass in your hand and a foggy head.

The bottom line is that you simply don’t need alcohol to be healthy, and the less you drink, the lower your long-term risk. If you want more years of high-quality life, this is a lever worth pulling.

Exercise Habits

If there’s one universal prescription I’d give to every client, it’s to move your body, regularly, for life. Exercise isn’t just about looking better or getting stronger in the gym, it’s probably the single most reliable way to add high-quality years to your lifespan.

People often ask, “What matters more, exercise or nutrition?” And the honest answer is very hard to disentangle, even though the numbers don’t seem to suggest this.

Here’s why:

- In diet studies, we usually compare a poor-quality diet to a decent or optimised diet. There’s no true “zero diet” group (since everyone eats).

- In exercise studies, there actually is a “no intervention” group, which is completely bed-bound individuals.

Unfortunately, most studies use “sedentary” groups as the no intervention group for exercise, and this is more like comparing an “ok diet” to a “healthy diet”. You can certainly harm yourself with poor practices (extremely high sugar, trans fats, ultra-processed foods, etc.), and this isn’t exactly the same effect as just being sedentary.

Beyond this, exercise is also one of those key stone habits, that tends to cause people to tidy up a lot of other habits. Most people who start exercising regularly, tend to start working more on optimising their diet, sleep and stress management. So, even if the magnitude of benefit is lower than other interventions, it does tend to lead to a cascade of benefits.

Whether your goal is longevity, energy, independence, or simply feeling better in your own skin, exercise is non-negotiable and the single most powerful, universally available tool you have.

Let’s break it down into the categories that matter most:

Aerobic Activity (Cardio)

Research is crystal clear that getting at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week (think brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or jogging), or 75 minutes of vigorous activity (like running or high-intensity intervals), is linked to an extra 3-4 years of life.

If you go beyond the baseline, the benefits climb even higher. People with elite aerobic fitness levels (the top performers for their age) can add 6-7 extra years compared to those who are sedentary. That’s a massive return for something as simple as making time for regular movement.

Resistance Training (Strength Work)

Cardio isn’t the whole story. Strength training at least two times per week is linked to a 10-17% lower risk of death from all causes, which works out to roughly an extra 1-2 years of life.

In practice, strength training keeps you mobile, independent, and resilient. It protects your bones, helps regulate blood sugar, maintains muscle mass (which declines naturally with age), and prevents the frailty that often makes the difference between thriving and struggling later in life. So, while it may not have a huge effect on lifespan, it has a huge effect on healthspan (the quality of your years).

Daily Steps

One of the easiest ways to gauge whether you’re getting enough general movement is by tracking your daily step count. You don’t need to obsess over getting 10,000 steps, that number was originally a marketing slogan, not a scientific benchmark.

Here’s what the data shows:

- 7,000-8,000 steps per day is a strong threshold for health and longevity. Hitting this range is linked with a 30-50% lower risk of early death compared to fewer steps.

- Going higher, up to 10,000-15,000 steps per day, appears to add even more benefit, particularly for cardiovascular and metabolic health.

- Importantly, the biggest jump in benefit happens when you move from sedentary (<4,000 steps/day) to a consistent 7,000+ steps/day.

So, if you’re sitting all day and barely moving, even adding a daily 20-30 minute walk can actually quite drastically transform your health trajectory.

Priority Action: Meet the Baseline, Then Progress

Your first goal should always be to hit the baseline guidelines:

- 150 minutes of moderate cardio per week (or 75 vigorous), and

- 2+ sessions of resistance training, and

- Aim for 7,000+ steps daily as your everyday movement baseline.

Once you’ve built that foundation, the next step is to progress gradually. That could mean adding an extra walk, increasing your weekly cardio minutes, upping the intensity, or getting stronger in the gym. Build the baseline first, then optimise later.

Diet Habits

When it comes to nutrition, unfortunately, there’s no magic bullet. Forget about the “superfood of the week” or the latest diet trend that promises to melt fat in 30 days. What matters most for your health and longevity is the overall quality and quantity of your diet, what you consistently eat, day after day, year after year.

The good news is that you don’t need to eat perfectly. You just need to shift your diet in the direction of calorie-appropriate, whole, minimally processed food diet. That’s what the Mediterranean pattern does so well, and it’s why it’s the most consistently researched eating style in longevity studies.

Here’s what the evidence tells us:

Mediterranean / Whole-Food Diet

People who follow a calorie-appropriate Mediterranean or whole-food-based eating pattern (rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, fish, and lean protein) gain an average of 9-11 extra years of life compared to those on a poor-quality diet. That’s about as powerful as quitting smoking.

Fruits & Vegetables

Eating at least five servings per day of fruit and veg is linked with 2-3 additional years of life. Higher fruit and veg intake reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers. They also make the diet tasty, which increases adherence.

Fibre

Fibre is one of the unsung heroes of nutrition. For every 10 grams per day you add, overall mortality risk drops by about 10%. Over a lifetime, that translates into 1-2 extra years of life. The key is aiming for around 10 grams of fibre per 1,000 calories eaten, which you’ll naturally hit if you’re eating plenty of plants and whole foods.

Protein (Key for Healthspan)

Adequate protein intake is crucial for maintaining muscle mass, strength, and function as you age. Without enough protein, the risk of sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) skyrockets, leading to frailty, falls, and loss of independence.

- A good target for most adults is at least 1-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day (higher than the outdated minimum RDA of 0.8 g/kg). However, some of you may actually need a lot more than this, and intakes around ~2-2.5 g/kg/day may make sense.

- Protein quality matters too. You want to try and include a mix of lean animal sources (fish, poultry, dairy, eggs) and plant proteins (vegetables, beans, lentils, tofu, tempeh, quinoa).

- Distribute it across the day (20-40 grams per meal) rather than cramming it all into dinner, like most people try to do. This maximises muscle protein synthesis.

The result of getting sufficient protein is better recovery, stronger muscles, higher bone density, improved satiety (less hunger!), and a much higher chance of staying active and independent well into later life.

Sugar-Sweetened Drinks

Drinking sugary beverages daily (soda, sweetened teas, energy drinks) is linked with about 2 years of life lost, plus a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Cutting them out is one of the easiest wins you can make.

Saturated Fat

Diets consistently high in saturated fat (especially from processed meats, fried foods, and butter-heavy cooking) increase cardiovascular risk. That directly adds up to a 1-2 year reduction in lifespan. Swapping some of those calories for unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish) is a smart move for heart health. Heart disease is one of the biggest killers of humans, so every little smart change you can make here goes a very long way.

Priority Action: Shift Diet Quality Step by Step

Don’t try to overhaul your diet overnight as that almost always backfires. Instead, focus on one small upgrade at a time:

- Add a serving of vegetables to your lunch or dinner.

- Swap one sugar soda for water, sparkling water or even the sugar-free version.

- Replace refined grains with whole grains a few times per week.

- Add beans, lentils, or nuts as protein sources in some meals.

- Include a high-protein food at every meal (chicken, eggs, yogurt, fish, tofu, lentils).

Over weeks and months, these steps add up to a pattern that dramatically improves both lifespan and quality of life.

From a coaching perspective, I remind clients that diet isn’t about perfection, it’s about direction. Every step you take toward a more whole-food, calorie-appropriate, Mediterranean-style, protein-adequate diet is an investment in more healthy, active years down the road. You don’t need to get it perfect straight out of the gates though!

Other Lifestyle Factors

When people think about health, they usually go straight to diet and exercise. Those are absolutely essential, but they’re not the whole story. Sleep, stress, and social connection play enormous roles in both how long you live and, just as importantly, how good those years feel.

Sleep

Your body is designed to run on 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Fall short of that consistently, and the effects add up to a higher risk of heart disease, obesity, diabetes, cognitive decline, and early death. In fact, short sleepers (under 6 hours) lose about 2-4 years of life expectancy compared to those who get enough rest.

Fortunately, sleep is a lever you can pull almost immediately. The main reason people aren’t sleeping enough generally isn’t some sort of sleep condition, it is simply poor sleep hygiene practices. Even an extra 30-60 minutes per night makes a difference for recovery, energy, and long-term health, and this can usually be fairly easily done by just turning off the tv, getting off your phone and getting into bed a bit earlier.

Stress Management

Chronic, unmanaged stress doesn’t just make you feel burned out, it quite literally shortens life. People with high stress levels and no coping strategies have a 30-40% higher risk of early death, translating to around 2 years lost. Stress keeps your body in a state of high alert, raising blood pressure, driving inflammation, and disrupting sleep and digestion.

But stress itself isn’t the enemy, it’s unmanaged stress that’s harmful. Practices like walking, journaling, meditation, breathwork, or simply taking breaks outdoors all buffer the physiological toll of stress.

Social Connection

This one surprises people the most. Strong social ties (friendships, family, community, etc.) are linked to 5-7 extra years of life. On the flip side, loneliness and social isolation are often said to raise mortality risk as much as smoking a pack of cigarettes a day. Humans are wired to connect, and when that need isn’t met, health suffers deeply.

Building and maintaining relationships is just as important as logging workouts or prepping meals! Regular phone calls, shared meals, joining clubs, volunteering, or whatever else you can do to get out of the house and talk to people, they all count.

Priority Action: Support Mental & Social Health, Not Just Physical

You can eat perfectly and train hard, but if you’re sleeping 5 hours a night, drowning in stress, and cut off from meaningful connection, you’re leaving massive years of life on the table.

So ask yourself honestly:

- Am I giving my body enough time to recharge with sleep?

- Do I have a regular practice for handling stress?

- Am I investing in friendships and family as much as I invest in my workouts or nutrition?

Your health isn’t just about muscles, macros, or mileage. It’s also about peace of mind and the people you share life with.

Body Composition & Biomarkers

Diet and exercise habits are the inputs, but your body composition and blood markers are some of the most important outputs. They tell us how your lifestyle is translating into measurable health outcomes. Think of them as your body’s scorecard.

You get a lot of benefit from simply eating better and exercising regularly, but you do actually get even more benefit if you accomplish some specific target outcomes.

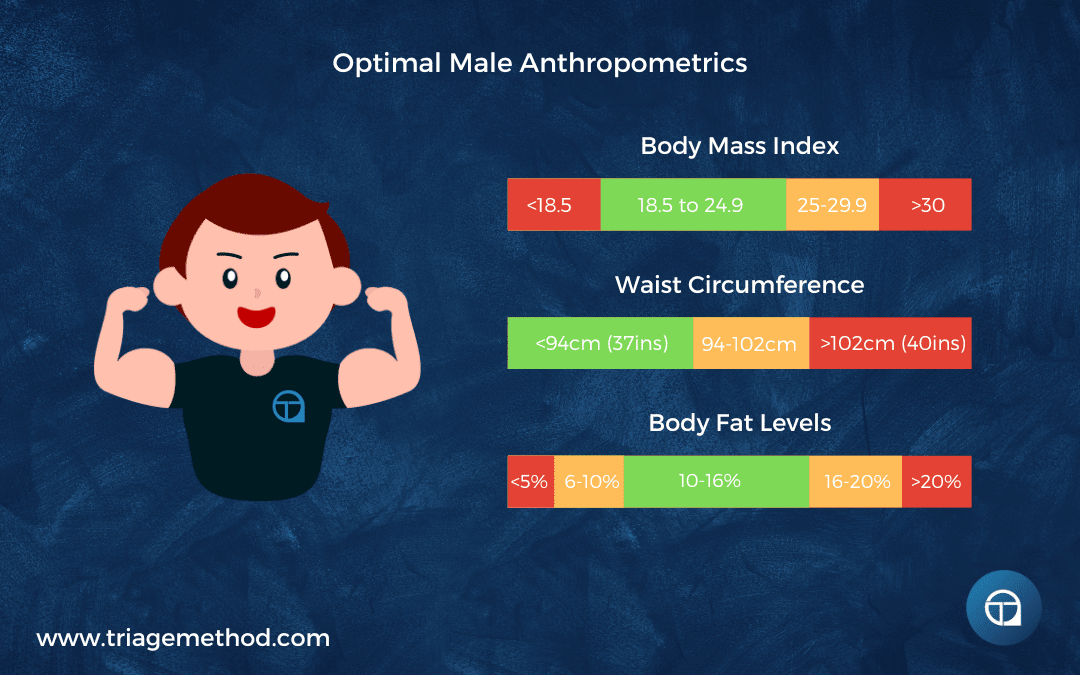

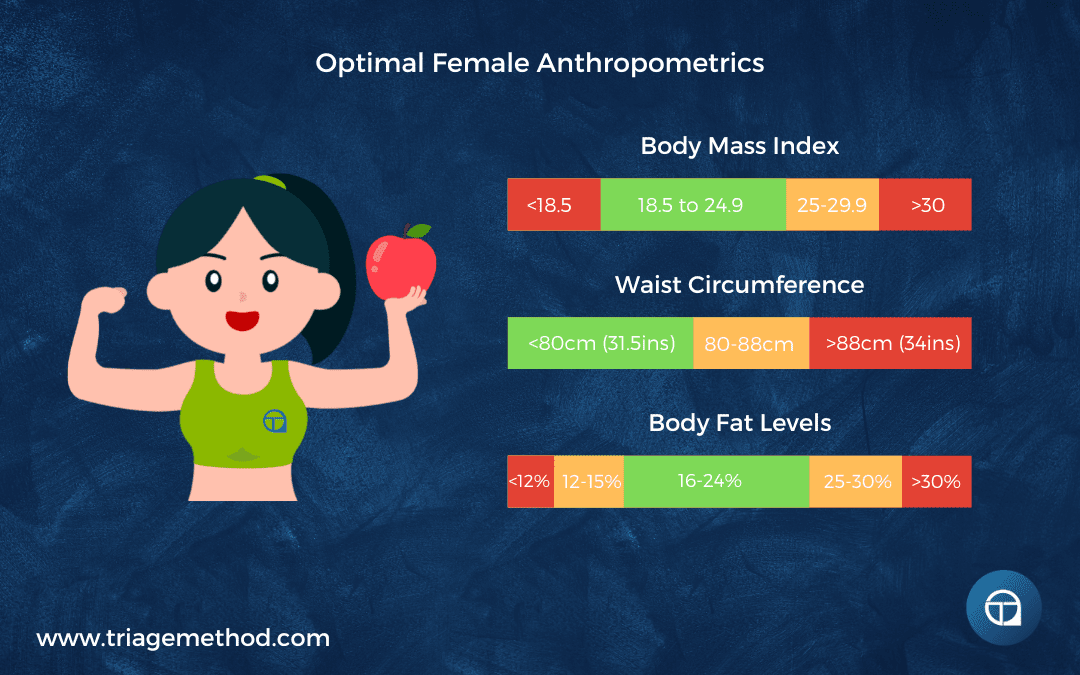

BMI (Body Mass Index)

BMI isn’t a perfect tool, but on a population level, it tracks pretty well with health risks. At the extremes, the effect is clear that being obese (BMI ≥35) is linked to losing 3-10 years of life expectancy. The higher the BMI, the steeper the risk.

For health, we ideally want to fall into the healthy weight category of BMI.

- Below 18.5 = underweight

- 18.5-24.9 = healthy weight

- 25-29.9 = overweight

- 30-34.9 = obese (class I)

- 35+ = obese (class II–III)

You can calculate BMI with the formula:

BMI = weight (kg) ÷ [height (m)]²

But to make it simpler, here’s a quick lookup table:

| Height | Weight for BMI 18.5 | Weight for BMI 25 | Weight for BMI 30 | Weight for BMI 35 |

| 1.60 m (5’3”) | 47 kg (104 lb) | 64 kg (141 lb) | 77 kg (170 lb) | 90 kg (198 lb) |

| 1.70 m (5’7”) | 54 kg (119 lb) | 72 kg (159 lb) | 87 kg (192 lb) | 102 kg (225 lb) |

| 1.80 m (5’11”) | 60 kg (132 lb) | 81 kg (179 lb) | 97 kg (213 lb) | 113 kg (249 lb) |

| 1.90 m (6’3”) | 67 kg (148 lb) | 90 kg (198 lb) | 108 kg (238 lb) | 124 kg (273 lb) |

That said, BMI can be misleading for individuals with lots of muscle mass, which is why we also look at more direct measures.

Body Fat Percentage

Carrying excess fat mass, especially visceral fat around the organs, raises the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. On average, being in a high-fat range (above ~20% for men, above ~30% for women) shortens life by 2-5 years.

This is why strength training, calorie intake and protein intake matter so much, as they can help shift body composition toward more muscle, less fat.

Waist Circumference

Sometimes even more telling than BMI, waist size reflects central fat (the kind that’s most dangerous metabolically). A waist over 102 cm (40 in) in men, or 88 cm (35 in) in women is associated with 3-5 years of life lost, even if BMI looks “normal.”

LDL Cholesterol

Blood lipids are another powerful marker. For every 1 mmol/L increase in LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, the risk of vascular events rises about 20%, translating to roughly 2-3 years of life lost over time.

The sweet spot for longevity is keeping LDL below 2.5 mmol/L. That usually comes from a mix of diet (reducing saturated fat, adding fibre and unsaturated fats), exercise, and for some people, medication, if lifestyle alone isn’t enough.

Blood Lipid Ranges (General Guidelines)

| Marker | Optimal Range | Borderline / High Risk |

| Total Cholesterol | < 5.0 mmol/L | > 6.0 mmol/L |

| LDL Cholesterol | < 2.5 mmol/L | > 3.5 mmol/L |

| HDL Cholesterol | > 1.0 mmol/L (men) / > 1.2 mmol/L (women) | < 1.0 mmol/L |

| Triglycerides | < 1.7 mmol/L | > 2.3 mmol/L |

(Note: exact cut-offs may vary slightly between guidelines, but these are widely accepted targets.)

Priority Action: Improve Body Composition & Target LDL <2.5 mmol/L

From a coaching perspective, this is about playing the long game.

- Strength training, cardio, and protein → build muscle, reduce fat.

- Calorie-appropriate, whole-food, Mediterranean-style diet → improves waist size, blood lipids, and metabolic health.

- Regular check-ups → track blood markers and catch problems early.

Lifestyle changes can shift these markers in just weeks to months, and small improvements add up. By keeping body fat, waist circumference, and LDL in check, you’re protecting yourself from the diseases that cut healthspan short.

Exercise Outcomes (Fitness Markers)

It’s one thing to look at how often you work out. But the real measure of whether your exercise habits are paying off is in your fitness outcomes (how your body actually performs). These markers are some of the strongest predictors we have for long-term health and lifespan.

VO₂ Max (Aerobic Fitness)

VO₂ max is a measure of how much oxygen your body can use during exercise, and is essentially how fit your heart, lungs, and muscles are. Being in the top 25% for your age and sex is linked to about 5 extra years of life compared to being in the bottom quartile.

That’s a bigger impact than almost any other single fitness measure. Improving VO₂ max means your heart pumps more efficiently, your blood vessels stay healthier, and your body handles stress better.

Approximate VO₂ Max Norms by Age (mL/kg/min)

| Age (yrs) | Men – Average | Men – Top 25% | Women – Average | Women – Top 25% |

| 20-29 | 42-46 | 50+ | 33-37 | 40+ |

| 30-39 | 40-43 | 47+ | 31-35 | 38+ |

| 40-49 | 37-40 | 44+ | 28-32 | 35+ |

| 50-59 | 34-37 | 41+ | 26-30 | 33+ |

| 60+ | 30-33 | 37+ | 24-27 | 30+ |

(Ranges vary slightly depending on the source.)

If you don’t know your VO₂ max, get it tested, try to calculate it based on running pace, or use some sort of fitness tracking wearable to estimate it.

Improving VO₂ max takes time, but there are specific protocols that can really help to improve VO₂ max. While you may not be able to improve yours to elite levels, almost everyone can get theirs into the top 25% level.

Resting Heart Rate (RHR)

Your resting heart rate is another simple but powerful marker. A resting heart rate under 60 bpm is linked to much better cardiovascular health, while a resting heart rate over 90 bpm is associated with 9 years shorter lifespan.

Luckily, consistent aerobic training, stress management, and good sleep all lower RHR.

Strength (Grip, Squat, Hinge, Push, Pull)

Muscular strength isn’t just about lifting heavy in the gym, it’s a direct predictor of survival and independence. People in the weakest quartile for grip strength face a 50-67% higher risk of mortality compared to stronger peers. But grip strength is just a proxy. For a full picture of functional strength, think about the big movement patterns:

- Squat (lower body strength): Can you squat your bodyweight (men) or 0.75× bodyweight (women)?

- Hinge (posterior chain): Can you deadlift 1.25× bodyweight (men) or bodyweight (women)?

- Push (upper body pushing strength): Can you do 20+ strict push-ups (men) or 10+ (women)?

- Pull (upper body pulling strength): Can you do 5+ unassisted pull-ups (men) or 1+ (women)?

Meeting these standards isn’t about chasing gym numbers for their own sake, it’s about having the strength reserve to stay mobile, resilient, and independent as you age. Most people will be able to hit these levels within 1-2 years of training.

Building your strength may not lead to a huge jump in your lifespan, but it does drastically improve your quality of life and overall healthspan. Being able to freely engage with the world around you is incredibly freeing and generally leads to much higher levels of life satisfaction and engagement.

Priority Action: Build Aerobic Capacity + Strength

If exercise habits are the “inputs,” fitness outcomes are the “outputs.” Your priority is to:

- Build aerobic capacity → improve VO₂ max, lower resting heart rate.

- Build strength across movement patterns → not just for longevity, but for independence and quality of life.

Don’t just check the box that you “went to the gym.” Train with purpose, track your progress, and aim to improve these markers. They’re some of the most powerful predictors of how long and how well you’ll live.

Health Priority Quiz: Putting It All Together

Now, we’ve looked at the pieces one by one. Smoking, alcohol, exercise, diet, sleep, stress, social connection, body composition, and fitness markers. Each one matters, but the real power comes when you stack them together.

Healthy habits don’t just add years in isolation, they multiply each other’s benefits. For example:

- A non-smoker who is also physically active, eats a nutrient-dense diet, gets consistent sleep, and maintains strong social ties can expect to live 10-18 years longer than someone who misses the mark on all of those.

- And those extra years aren’t just “more candles on the cake”, they’re healthier, higher-quality years where you can stay active, independent, and engaged in life.

That’s why I designed the quiz the way I did. It helps you identify the biggest priority to tackle right now. Once you’ve nailed that, you move to the next. Step by step, you build momentum and stack habits in a way that’s sustainable.

So before you get distracted by the latest random supplement, gadget, or so-called “biohack,” ask yourself: Do I have the big rocks in place?

- Am I smoke-free?

- Am I active and strong?

- Am I eating mostly whole, unprocessed foods with enough protein and fibre? Is the diet calorie-appropriate?

- Am I sleeping, managing stress, and staying connected with people I care about?

If the answer is “yes” across the board, congratulations, you’re already doing the things that science says add a decade or more to life. If the answer is “no” in one or more areas, you’ve found your starting point.

Ultimately, you should master the fundamentals first. They’re not glamorous, but they’re what actually move the needle for both healthspan and lifespan. Once the big rocks are in place, then, and only then, does it make sense to experiment and chase other things.

If you want to understand what you should be prioritising, or you need help creating a plan of action, we can help you do this. You can reach out to us and get online coaching, or alternatively, you can interact with our free content.

If you want more free information on nutrition and exercise, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

Li Y, Pan A, Wang DD, et al. Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the U.S. Population. Circulation. Published online April 30, 2018. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047 Fadnes, L.T., Celis-Morales, C., Økland, JM. et al. Life expectancy can increase by up to 10 years following sustained shifts towards healthier diets in the United Kingdom. Nat Food 4, 961–965 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00868-w Reimers CD, Knapp G, Reimers AK. Does physical activity increase life expectancy? A review of the literature. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:243958. doi:10.1155/2012/243958 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3395188/ Gaye, B., Valentin, E., Xanthakis, V. et al. Association between change in heart rate over years and life span in the Paris Prospective 1, the Whitehall 1, and Framingham studies. Sci Rep 14, 20052 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70806-8 Chen XJ, Barywani SB, Hansson PO, et al. Impact of changes in heart rate with age on all-cause death and cardiovascular events in 50-year-old men from the general population. Open Heart. 2019;6(1):e000856. Published 2019 Apr 15. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2018-000856 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6519434/ Bohannon RW. Grip Strength: An Indispensable Biomarker For Older Adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1681-1691. Published 2019 Oct 1. doi:10.2147/CIA.S194543 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6778477/ Rantanen T, Masaki K, He Q, Ross GW, Willcox BJ, White L. Midlife muscle strength and human longevity up to age 100 years: a 44-year prospective study among a decedent cohort. Age (Dordr). 2012;34(3):563-570. doi:10.1007/s11357-011-9256-y https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3337929/ Taylor DH Jr, Hasselblad V, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Sloan FA. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):990-996. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.6.990 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1447499/ Le TTT, et al. The Benefits of Quitting Smoking at Different Ages. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2024;67(5):684-688. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2024.05.017 (S0749379724002174). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379724002174 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Benefits of Quitting Smoking. CDC – Smoking and Tobacco Use. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed [10/09/2025]. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/benefits-of-quitting.html Zhang D, Shen X, Qi X. Resting heart rate and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2016;188(3):E53-E63. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150535 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4754196/ Wen CP, Chen CH, Nauman J, et al. Resting heart rate – The forgotten risk factor? Comparison of resting heart rate and hypertension as predictors of all-cause mortality in 692,217 adults in Asia and Europe. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2025;89:35-44. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2025.01.007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39894380/ Jensen MT, Marott JL, Lange P, et al. Elevated resting heart rate, physical fitness and all-cause mortality. Heart. 2013;99(12):882–887. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304963. https://heart.bmj.com/content/99/12/882 Bingham S, Riboli E. Diet and cancer–the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(3):206-215. doi:10.1038/nrc1298 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14993902/ Global BMI Mortality Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju ShN, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):776-786. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4995441/ Flegal KM, Ioannidis JPA, Doehner W. Flawed methods and inappropriate conclusions for health policy on overweight and obesity: the Global BMI Mortality Collaboration meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(1):9-13. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12378 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6438342/ Nowak MM, Niemczyk M, Gołębiewski S, Pączek L. Impact of Body Mass Index on All-Cause Mortality in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024;13(8):2305. Published 2024 Apr 16. doi:10.3390/jcm13082305 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11051237/ Knowles R, Carter J, Jebb SA, Bennett D, Lewington S, Piernas C. Associations of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Fat Mass With Incident Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study of UK Biobank Participants. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(9):e019337. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.019337 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33870707/ Li CI, Liu CS, Lin CH, Yang SY, Li TC, Lin CC. Independent and joint associations of skeletal muscle mass and physical performance with all-cause mortality among older adults: a 12-year prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):597. Published 2022 Jul 18. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03292-0 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9295364/ Kuk JL, Katzmarzyk PT, Nichaman MZ, Church TS, Blair SN, Ross R. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(2):336-341. doi:10.1038/oby.2006.43 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16571861/ Saad RK, Ghezzawi M, Horanieh R, et al. Abdominal Visceral Adipose Tissue and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:922931. Published 2022 Aug 22. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.922931 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9446237/ Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(1):39-48. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675355 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17576866/ Ng, A., Wai, D., Tai, E. et al. Visceral adipose tissue, but not waist circumference is a better measure of metabolic risk in Singaporean Chinese and Indian men. Nutr & Diabetes 2, e38 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2012.12 Linge J, Petersson M, Forsgren MF, Sanyal AJ, Dahlqvist Leinhard O. Adverse muscle composition predicts all-cause mortality in the UK Biobank imaging study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(6):1513-1526. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12834 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8718078/ Hu J, Chen X, Yang J, et al. Association between fat mass and mortality: analysis of Mendelian randomization and lifestyle modification. Metabolism. 2022;136:155307. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2022.155307 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36058288/ Jayedi A, Soltani S, Zargar MS, Khan TA, Shab-Bidar S. Central fatness and risk of all cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 72 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2020;370:m3324. Published 2020 Sep 23. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3324 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7509947/ Harris E. Study: Waist-to-Hip Ratio Might Predict Mortality Better Than BMI. JAMA. 2023;330(16):1515-1516. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19205 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37792387/ Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):275-286. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00952.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22106927/ Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315-2381. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4986030/ Rao G, Powell-Wiley TM, Ancheta I, et al. Identification of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk in Ethnically and Racially Diverse Populations: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(5):457-472. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000223 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26149446/ Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21067804/ Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459-2472. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28444290/ Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Neff DR, Voros S, Giugliano RP, Smith GD, Fazio S, Sabatine MS. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2144–2153. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604304 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1604304 Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1410489 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26039521/ Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615664 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28304224/ Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097-2107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801174 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30403574/ Erviti J, Wright J, Bassett K, et al. Restoring mortality data in the FOURIER cardiovascular outcomes trial of evolocumab in patients with cardiovascular disease: a reanalysis based on regulatory data. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12):e060172. Published 2022 Dec 30. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060172 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9809302/ Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD011737. Published 2020 Aug 21. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32827219/ Jenkins DJ, Jones PJ, Lamarche B, et al. Effect of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods given at 2 levels of intensity of dietary advice on serum lipids in hyperlipidemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(8):831-839. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1202 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21862744/ Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):e34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800389 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29897866/ Hendryx M, Manson JE, Ostfeld RJ, et al. Intentional Weight Loss, Waist Circumference Reduction, and Mortality Risk Among Postmenopausal Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(3):e250609. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.0609 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2831077 Lee WJ, Peng LN, Loh CH, Chen LK, et al. Effect of Body Weight, Waist Circumference and Their Changes on Mortality: A 10-Year Population-Based Study. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2018;22(2). doi:10.1007/s12603-018-1042-4 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1279770723021917 Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459-2472. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5837225/References and Further Reading