Tempo is one of the most underutilised and poorly understood training variables, and it is actually an important variable to grasp if you want to get the most out of your resistance training. It isn’t even a difficult concept to grasp, yet many people willfully ignore it.

We have actually already touched on the topic of tempo in this article series on exercise, as we discussed the stretch-shortening cycle in the article on understanding reps. However, there is more to the discussion than just the stretch-shortening cycle.

However, to really dig into this topic, I am going to just assume that you already understand why exercise is important, the goals of exercise, the types of exercise we have available to us, and you have a rough idea of the general exercise guidelines. It would also be helpful if you had a good understanding of why and how we use resistance training to build muscle and strength. I am also going to assume that if you intend to use this information to make better exercise programs, you have already spent some time thinking about your exercise selection and have ensured it is appropriate for your goals.

If you haven’t already, it would be incredibly helpful to read our article on understanding reps, as this does cover a lot of stuff around reps that will allow you to better understand and utilise the information in this article. Our article on RIR and RPE is also quite helpful in rounding out your knowledge of reps.

You can also visit our exercise hub for more content on exercise.

Before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Now, with all that out of the way, we can actually get stuck into the discussion of tempo!

Tempo

Time Under Tension (TUT)

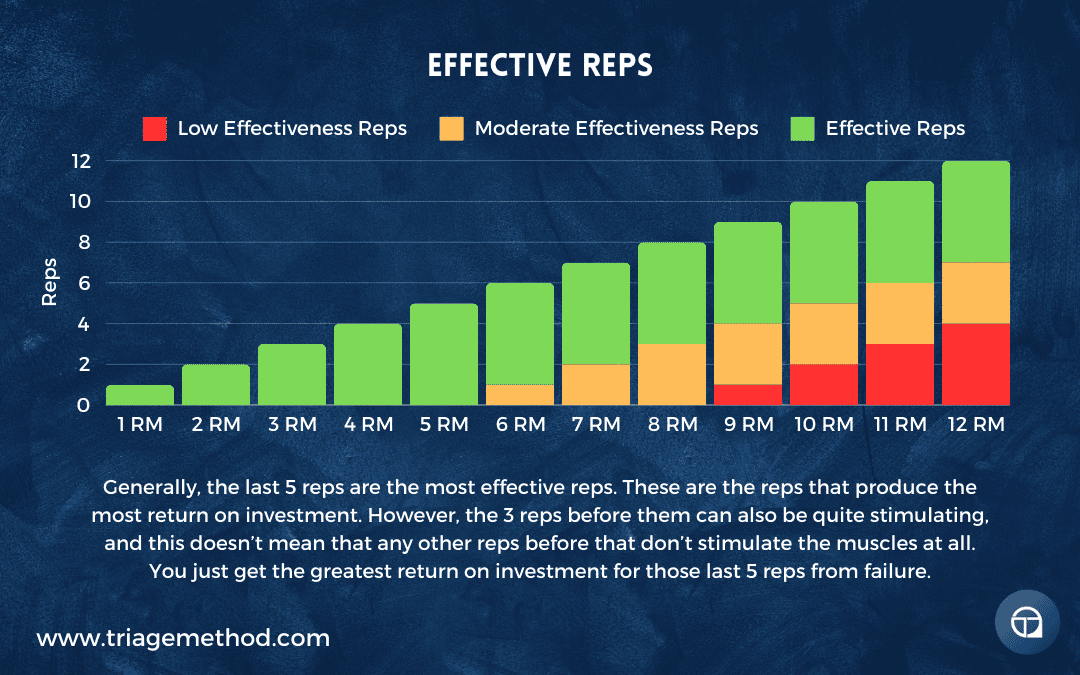

The more scientific explanation relates to motor unit recruitment and overall muscle physiology. A motor unit consists of a motor neuron and the muscle fibres it innervates. Different motor units are activated based on the demands placed on the muscle. According to the size principle, smaller motor units (with slower-twitch muscle fibres) are recruited first, followed by larger motor units (with fast-twitch muscle fibres) as the intensity of the effort increases.

Lifting heavy weights requires a greater force output, which in turn necessitates the recruitment of higher-threshold motor units, including those with fast-twitch muscle fibres that are essential for muscle hypertrophy and strength. To achieve full motor unit recruitment, maximal or near-maximal effort is often required. Heavy weights provide the necessary stimulus to activate these high-threshold units effectively.

While increasing TUT can contribute to muscle growth by increasing the duration of muscle activation, it alone does not guarantee full motor unit recruitment. Full motor unit recruitment is a critical factor in maximising muscle growth and strength gains. Lighter weights lifted for longer periods may predominantly recruit low-threshold motor units.

Motor unit recruitment also helps to understand the concept of effective reps. During the final reps of a set, the muscle fibres that are recruited first (slow-twitch) become fatigued, necessitating the recruitment of additional fast-twitch fibres. This leads to maximal motor unit recruitment, providing a robust stimulus for muscle growth. The effective reps are the ones that cause full motor unit recruitment.

Excessively slow reps (high TUT), when taken to or close to failure, can lead to full motor unit recruitment. However, you are potentially going to be more limited by excessive metabolite build-up (the muscle “burn” becomes too much), cell swelling (the pump becomes too much), cardiovascular fatigue (you get out of breath) or mental fatigue (you get bored or demotivated), rather than reaching full motor unit recruitment.

You are also more likely to be limited by non-target muscles when training with excessively slow reps. For example, your grip may fatigue much quicker than your back muscles when training your back. Your shoulders or triceps may fatigue much quicker than your chest muscles when training your chest. Your lower back may fatigue more quickly than your quads or hamstrings when training your legs. This can be overcome to some degree by only using isolation exercises that have a high degree of stability when training with a high TUT. However, this does limit your overall potential exercise selection, and some of the less obvious benefits of resistance training (i.e. compound movements may strengthen minor muscles and improve general robustness, while isolation exercises may not provide the same benefits).

Another drawback of excessively long TUT is more practical in nature. It simply takes a lot longer to get a training session completed when you use excessively long TUT. Doing 3 sets of 10, with a rest period of 2 minutes between sets, and with each rep taking 3 seconds total, takes 5.5-7 minutes long (depending on whether you count 2 or 3 rest periods). Whereas doing 3 sets of 10, with a rest period of 2 minutes between sets, and with each rep taking 8 seconds total, takes 8-9.5 minutes long.

This may not seem like all that much, but if you only have an hour to workout, you get dramatically less overall volume done when using excessively long TUT. Volume is a key variable that drives muscle growth and strength gain (which we will discuss in a future article), so we don’t want to reduce volume just so we can train excessively slowly.

Now, excessive TUT can be used to target metabolic stress. So it does have some use, but as metabolic stress isn’t the main driver of muscle/strength gain, we likely don’t want to dedicate the majority of our training time to it. But it is a tool in our toolbox.

How To Use Tempo

Tempo can be used to help standardise your reps, and make your last rep look as good as your first rep.

Tempo Conclusion

Tempo is a crucial resistance training variable that is often overlooked. Understanding and manipulating the components of tempo, such as the eccentric, isometric, and concentric phases, allows you to customise your training for specific goals.

While time under tension (TUT) sounds like it is important, ultimately, it shouldn’t be a huge focus in your training. So we don’t want to focus on tempo so much that it leads us to use excessively light weights.

However, in most instances, you do want to be in control of your reps, and you do want to standardise your reps. Having an assigned tempo allows you to do this.

As with everything, there is always more to learn, and we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface with all this stuff. However, if you are interested in staying up to date with all our content, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter and bookmarking our free content page. We do have a lot of content on how to design your own exercise program on our exercise hub.

If you would like more help with your training (or nutrition), we do also have online coaching spaces available.

We also recommend reading our foundational nutrition article, along with our foundational articles on sleep and stress management, if you really want to learn more about how to optimise your lifestyle. If you want even more free information on exercise, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

The previous article in this series is about RIR & RPE (Do You Need To Train To Failure) and the next article in this series is about Training Volume (How Many Sets Should You Do), if you are interested in continuing to learn about exercise program design. You can also go to our exercise hub to find more exercise content.

References and Further Reading

Furrer R, Hawley JA, Handschin C. The molecular athlete: exercise physiology from mechanisms to medals. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(3):1693-1787. doi:10.1152/physrev.00017.2022 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10110736/

Noto RE, Leavitt L, Edens MA. Physiology, Muscle. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30335291/

Stone MH, Hornsby WG, Suarez DG, Duca M, Pierce KC. Training Specificity for Athletes: Emphasis on Strength-Power Training: A Narrative Review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022;7(4):102. Published 2022 Nov 16. doi:10.3390/jfmk7040102 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9680266/

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Stone MH. The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):765-785. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0862-z https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29372481/

Reggiani C, Schiaffino S. Muscle hypertrophy and muscle strength: dependent or independent variables? A provocative review. Eur J Transl Myol. 2020;30(3):9311. Published 2020 Sep 9. doi:10.4081/ejtm.2020.9311 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7582410/

Wilson JM, Loenneke JP, Jo E, Wilson GJ, Zourdos MC, Kim JS. The effects of endurance, strength, and power training on muscle fiber type shifting. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(6):1724-1729. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318234eb6f https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21912291/

Buckner SL, Jessee MB, Mouser JG, et al. The Basics of Training for Muscle Size and Strength: A Brief Review on the Theory. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(3):645-653. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002171 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31652235/

Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojdała G, Gołaś A. Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):4897. Published 2019 Dec 4. doi:10.3390/ijerph16244897 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950543/

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Van Every DW, Plotkin DL. Loading Recommendations for Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Local Endurance: A Re-Examination of the Repetition Continuum. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(2):32. Published 2021 Feb 22. doi:10.3390/sports9020032 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7927075/

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Buchan D, Baker JS. Weekly Training Frequency Effects on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):36. Published 2018 Aug 3. doi:10.1186/s40798-018-0149-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30076500/

Behm DG, Young JD, Whitten JHD, et al. Effectiveness of Traditional Strength vs. Power Training on Muscle Strength, Power and Speed with Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:423. Published 2017 Jun 30. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00423 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5491841/

Maestroni L, Read P, Bishop C, et al. The Benefits of Strength Training on Musculoskeletal System Health: Practical Applications for Interdisciplinary Care. Sports Med. 2020;50(8):1431-1450. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01309-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32564299/

Folland JP, Williams AG. The adaptations to strength training : morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports Med. 2007;37(2):145-168. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17241104/

Iversen VM, Norum M, Schoenfeld BJ, Fimland MS. No Time to Lift? Designing Time-Efficient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2079-2095. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01490-1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8449772/

Calatayud J, Vinstrup J, Jakobsen MD, et al. Importance of mind-muscle connection during progressive resistance training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(3):527-533. doi:10.1007/s00421-015-3305-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26700744/

Colquhoun RJ, Gai CM, Aguilar D, et al. Training Volume, Not Frequency, Indicative of Maximal Strength Adaptations to Resistance Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1207-1213. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002414 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29324578/

Thomas MH, Burns SP. Increasing Lean Mass and Strength: A Comparison of High Frequency Strength Training to Lower Frequency Strength Training. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016;9(2):159-167. Published 2016 Apr 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4836564/

Schumann M, Feuerbacher JF, Sünkeler M, et al. Compatibility of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training for Skeletal Muscle Size and Function: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(3):601-612. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01587-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34757594/

de Santana DA, Castro A, Cavaglieri CR. Strength Training Volume to Increase Muscle Mass Responsiveness in Older Individuals: Weekly Sets Based Approach. Front Physiol. 2021;12:759677. Published 2021 Sep 30. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.759677 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8514686/

Balshaw TG, Maden-Wilkinson TM, Massey GJ, Folland JP. The Human Muscle Size and Strength Relationship: Effects of Architecture, Muscle Force, and Measurement Location. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(10):2140-2151. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002691 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33935234/

Bernárdez-Vázquez R, Raya-González J, Castillo D, Beato M. Resistance Training Variables for Optimization of Muscle Hypertrophy: An Umbrella Review. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:949021. Published 2022 Jul 4. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.949021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9302196/

Heidel KA, Novak ZJ, Dankel SJ. Machines and free weight exercises: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing changes in muscle size, strength, and power. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2022;62(8):1061-1070. doi:10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12929-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34609100/

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Baker JS. The Effect of Weekly Set Volume on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(12):2585-2601. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0762-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28755103/

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Hornsby WG, Stone MH. Training for Muscular Strength: Methods for Monitoring and Adjusting Training Intensity. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2051-2066. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01488-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34101157/

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Michalopoulos N, Fisher JP, et al. The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required for 1RM Strength in Powerlifters. Front Sports Act Living. 2021;3:713655. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.3389/fspor.2021.713655 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34527944/

Helms ER, Kwan K, Sousa CA, Cronin JB, Storey AG, Zourdos MC. Methods for Regulating and Monitoring Resistance Training. J Hum Kinet. 2020;74:23-42. Published 2020 Aug 31. doi:10.2478/hukin-2020-0011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33312273/

Ruple BA, Plotkin DL, Smith MA, et al. The effects of resistance training to near failure on strength, hypertrophy, and motor unit adaptations in previously trained adults. Physiol Rep. 2023;11(9):e15679. doi:10.14814/phy2.15679 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37144554/

Zourdos MC, Klemp A, Dolan C, et al. Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(1):267-275. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001049 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26049792/

Mangine GT, Serafini PR, Stratton MT, Olmos AA, VanDusseldorp TA, Feito Y. Effect of the Repetitions-In-Reserve Resistance Training Strategy on Bench Press Performance, Perceived Effort, and Recovery in Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2022;36(1):1-9. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004158 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34941608/

Mansfield SK, Peiffer JJ, Hughes LJ, Scott BR. Estimating Repetitions in Reserve for Resistance Exercise: An Analysis of Factors Which Impact on Prediction Accuracy. J Strength Cond Res. Published online August 31, 2020. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003779 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32881842/

Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857-2872. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20847704/

Baz-Valle E, Balsalobre-Fernández C, Alix-Fages C, Santos-Concejero J. A Systematic Review of The Effects of Different Resistance Training Volumes on Muscle Hypertrophy. J Hum Kinet. 2022;81:199-210. Published 2022 Feb 10. doi:10.2478/hukin-2022-0017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8884877/

Warneke K, Lohmann LH, Lima CD, et al. Physiology of Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy and Strength Increases: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2023;53(11):2055-2075. doi:10.1007/s40279-023-01898-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37556026/

Lawson D, Vann C, Schoenfeld BJ, Haun C. Beyond Mechanical Tension: A Review of Resistance Exercise-Induced Lactate Responses & Muscle Hypertrophy. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022;7(4):81. Published 2022 Oct 4. doi:10.3390/jfmk7040081 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9590033/

de Freitas MC, Gerosa-Neto J, Zanchi NE, Lira FS, Rossi FE. Role of metabolic stress for enhancing muscle adaptations: Practical applications. World J Methodol. 2017;7(2):46-54. Published 2017 Jun 26. doi:10.5662/wjm.v7.i2.46 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5489423/

Kaura V, Hopkins PM. Recent advances in skeletal muscle physiology. BJA Educ. 2024;24(3):84-90. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2023.12.003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38375493/

Sartori R, Romanello V, Sandri M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: implications in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):330. Published 2021 Jan 12. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20123-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33436614/

Dave HD, Shook M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Skeletal Muscle. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 28, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30725921/

Enoka RM, Stuart DG. Neurobiology of muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1992;72(5):1631-1648. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1631 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1601767/

Pate RR, Durstine JL. Exercise physiology and its role in clinical sports medicine. South Med J. 2004;97(9):881-885. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000140116.17258.F1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15455979/

Rivera-Brown AM, Frontera WR. Principles of exercise physiology: responses to acute exercise and long-term adaptations to training. PM R. 2012;4(11):797-804. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.10.007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23174541/

Kiens B, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF. Exercise physiology: from performance studies to muscle physiology and cardiovascular adaptations. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;117(9):943-944. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00874.2014 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25277739/

Pedersen BK. The Physiology of Optimizing Health with a Focus on Exercise as Medicine. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:607-627. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114339 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30526319/

Powers SK, Hogan MC. Advances in exercise physiology: exercise and health. J Physiol. 2021;599(3):769-770. doi:10.1113/JP281003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33521984/

Irvin CG. Exercise physiology. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1996;17(6):327-330. doi:10.2500/108854196778606356 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8993725/

Wackerhage H, Schoenfeld BJ. Personalized, Evidence-Informed Training Plans and Exercise Prescriptions for Performance, Fitness and Health. Sports Med. 2021;51(9):1805-1813. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01495-w https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8363526/

Baz-Valle E, Schoenfeld BJ, Torres-Unda J, Santos-Concejero J, Balsalobre-Fernández C. The effects of exercise variation in muscle thickness, maximal strength and motivation in resistance trained men. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226989. Published 2019 Dec 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226989 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6934277/

Zabaleta-Korta A, Fernández-Peña E, Torres-Unda J, Garbisu-Hualde A, Santos-Concejero J. The role of exercise selection in regional Muscle Hypertrophy: A randomized controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(20):2298-2304. doi:10.1080/02640414.2021.1929736 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34743671/

Lopez P, Radaelli R, Taaffe DR, et al. Resistance Training Load Effects on Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gain: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis [published correction appears in Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022 Feb 1;54(2):370]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(6):1206-1216. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002585 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33433148/

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations Between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(12):3508-3523. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002200 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn DI, Krieger JW. Effect of repetition duration during resistance training on muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(4):577-585. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0304-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25601394/

Mangine GT, Hoffman JR, Gonzalez AM, et al. The effect of training volume and intensity on improvements in muscular strength and size in resistance-trained men. Physiol Rep. 2015;3(8):e12472. doi:10.14814/phy2.12472 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4562558/

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120901559. Published 2020 Jan 21. doi:10.1177/2050312120901559 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6977096/

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Fisher JP, Steele J. The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required to Increase 1RM Strength in Resistance-Trained Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50(4):751-765. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01236-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31797219/

Schoenfeld BJ, Contreras B, Krieger J, et al. Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(1):94-103. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001764 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6303131/

Helms ER, Cronin J, Storey A, Zourdos MC. Application of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Training. Strength Cond J. 2016;38(4):42-49. doi:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000218 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4961270/

Pelland JC, Robinson ZP, Remmert JF, et al. Methods for Controlling and Reporting Resistance Training Proximity to Failure: Current Issues and Future Directions. Sports Med. 2022;52(7):1461-1472. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01667-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35247203/

Campos GE, Luecke TJ, Wendeln HK, et al. Muscular adaptations in response to three different resistance-training regimens: specificity of repetition maximum training zones. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;88(1-2):50-60. doi:10.1007/s00421-002-0681-6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12436270/

Arede J, Vaz R, Gonzalo-Skok O, et al. Repetitions in reserve vs. maximum effort resistance training programs in youth female athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020;60(9):1231-1239. doi:10.23736/S0022-4707.20.10907-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32586078/

Lovegrove S, Hughes LJ, Mansfield SK, Read PJ, Price P, Patterson SD. Repetitions in Reserve Is a Reliable Tool for Prescribing Resistance Training Load. J Strength Cond Res. 2022;36(10):2696-2700. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003952 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36135029/

Bastos V, Machado S, Teixeira DS. Feasibility and Usefulness of Repetitions-In-Reserve Scales for Selecting Exercise Intensity: A Scoping Review. Percept Mot Skills. Published online April 2, 2024. doi:10.1177/00315125241241785 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38563729/

Morishita S, Tsubaki A, Takabayashi T, Fu JB. Relationship between the rating of perceived exertion scale and the load intensity of resistance training. Strength Cond J. 2018;40(2):94-109. doi:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000373 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5901652/

D Egan A, B Winchester J, Foster C, R McGuigan M. Using Session RPE to Monitor Different Methods of Resistance Exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2006;5(2):289-295. Published 2006 Jun 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24260002/

Day ML, McGuigan MR, Brice G, Foster C. Monitoring exercise intensity during resistance training using the session RPE scale. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(2):353-358. doi:10.1519/R-13113.1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15142026/

Morishita S, Tsubaki A, Nakamura M, Nashimoto S, Fu JB, Onishi H. Rating of perceived exertion on resistance training in elderly subjects. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2019;17(2):135-142. doi:10.1080/14779072.2019.1561278 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30569775/

Boxman-Zeevi Y, Schwartz H, Har-Nir I, Bordo N, Halperin I. Prescribing Intensity in Resistance Training Using Rating of Perceived Effort: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Physiol. 2022;13:891385. Published 2022 Apr 29. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.891385 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35574454/

Dias MRC, Simão R, Saavedra FJF, Buzzachera CF, Fleck S. Self-Selected Training Load and RPE During Resistance and Aerobic Training Among Recreational Exercisers. Percept Mot Skills. 2018;125(4):769-787. doi:10.1177/0031512518774461 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29726740/

Halperin I, Emanuel A. Rating of Perceived Effort: Methodological Concerns and Future Directions. Sports Med. 2020;50(4):679-687. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01229-z https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31745731/

Spiering BA, Clark BC, Schoenfeld BJ, Foulis SA, Pasiakos SM. Maximizing Strength: The Stimuli and Mediators of Strength Gains and Their Application to Training and Rehabilitation. J Strength Cond Res. 2023;37(4):919-929. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004390 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36580280/

Schoenfeld BJ, Pope ZK, Benik FM, et al. Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(7):1805-1812. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26605807/

Baz-Valle E, Fontes-Villalba M, Santos-Concejero J. Total Number of Sets as a Training Volume Quantification Method for Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(3):870-878. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002776 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30063555/

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn DI, Vigotsky AD, Franchi MV, Krieger JW. Hypertrophic Effects of Concentric vs. Eccentric Muscle Actions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(9):2599-2608. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001983 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28486337/

Schoenfeld BJ. Does exercise-induced muscle damage play a role in skeletal muscle hypertrophy?. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(5):1441-1453. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31824f207e https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22344059/

Vaara JP, Kyröläinen H, Niemi J, et al. Associations of maximal strength and muscular endurance test scores with cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2078-2086. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823b06ff https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21997456/

Radaelli R, Fleck SJ, Leite T, et al. Dose-response of 1, 3, and 5 sets of resistance exercise on strength, local muscular endurance, and hypertrophy. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(5):1349-1358. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000758 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25546444/

Krieger JW. Single vs. multiple sets of resistance exercise for muscle hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(4):1150-1159. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d4d436 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20300012/

Pinto RS, Gomes N, Radaelli R, Botton CE, Brown LE, Bottaro M. Effect of range of motion on muscle strength and thickness. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2140-2145. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3b15 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22027847/

Kassiano W, Nunes JP, Costa B, Ribeiro AS, Schoenfeld BJ, Cyrino ES. Does Varying Resistance Exercises Promote Superior Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gains? A Systematic Review. J Strength Cond Res. 2022;36(6):1753-1762. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004258 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35438660/

Vieira AF, Umpierre D, Teodoro JL, et al. Effects of Resistance Training Performed to Failure or Not to Failure on Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Power Output: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(4):1165-1175. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003936 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33555822/

Schoenfeld BJ, Ratamess NA, Peterson MD, Contreras B, Sonmez GT, Alvar BA. Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(10):2909-2918. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24714538/

Carvalho L, Junior RM, Barreira J, Schoenfeld BJ, Orazem J, Barroso R. Muscle hypertrophy and strength gains after resistance training with different volume-matched loads: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2022;47(4):357-368. doi:10.1139/apnm-2021-0515 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35015560/

Vieira JG, Sardeli AV, Dias MR, et al. Effects of Resistance Training to Muscle Failure on Acute Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(5):1103-1125. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01602-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34881412/

Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Davies TB, Lazinica B, Krieger JW, Pedisic Z. Effect of Resistance Training Frequency on Gains in Muscular Strength: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(5):1207-1220. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0872-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29470825/

Aube D, Wadhi T, Rauch J, et al. Progressive Resistance Training Volume: Effects on Muscle Thickness, Mass, and Strength Adaptations in Resistance-Trained Individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2022;36(3):600-607. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003524 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32058362/

La Scala Teixeira CV, Motoyama Y, de Azevedo PHSM, Evangelista AL, Steele J, Bocalini DS. Effect of resistance training set volume on upper body muscle hypertrophy: are more sets really better than less?. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018;38(5):727-732. doi:10.1111/cpf.12476 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29024332/

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Haun C, Itagaki T, Helms ER. Calculating Set-Volume for the Limb Muscles with the Performance of Multi-Joint Exercises: Implications for Resistance Training Prescription. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(7):177. Published 2019 Jul 22. doi:10.3390/sports7070177 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31336594/

Nunes JP, Kassiano W, Costa BDV, Mayhew JL, Ribeiro AS, Cyrino ES. Equating Resistance-Training Volume Between Programs Focused on Muscle Hypertrophy. Sports Med. 2021;51(6):1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01449-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33826122/

Figueiredo VC, de Salles BF, Trajano GS. Volume for Muscle Hypertrophy and Health Outcomes: The Most Effective Variable in Resistance Training. Sports Med. 2018;48(3):499-505. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0793-0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29022275/

Rocha JNS, Pereira-Monteiro MR, Vasconcelos ABS, Pantoja-Cardoso A, Aragão-Santos JC, Da Silva-Grigoletto ME. Different resistance training volumes on strength, functional fitness, and body composition of older people: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2024;119:105303. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2023.105303 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38128241/

Hamarsland H, Moen H, Skaar OJ, Jorang PW, Rødahl HS, Rønnestad BR. Equal-Volume Strength Training With Different Training Frequencies Induces Similar Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Improvement in Trained Participants. Front Physiol. 2022;12:789403. Published 2022 Jan 5. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.789403 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8766679/

Lasevicius T, Ugrinowitsch C, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Effects of different intensities of resistance training with equated volume load on muscle strength and hypertrophy. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(6):772-780. doi:10.1080/17461391.2018.1450898 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29564973/

Jenkins ND, Housh TJ, Buckner SL, et al. Neuromuscular Adaptations After 2 and 4 Weeks of 80% Versus 30% 1 Repetition Maximum Resistance Training to Failure. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(8):2174-2185. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001308 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26848545/

Davies T, Orr R, Halaki M, Hackett D. Erratum to: Effect of Training Leading to Repetition Failure on Muscular Strength: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(4):605-610. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0509-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26893097/

Martorelli S, Cadore EL, Izquierdo M, et al. Strength Training with Repetitions to Failure does not Provide Additional Strength and Muscle Hypertrophy Gains in Young Women. Eur J Transl Myol. 2017;27(2):6339. Published 2017 Jun 27. doi:10.4081/ejtm.2017.6339 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28713535/

Morán-Navarro R, Pérez CE, Mora-Rodríguez R, et al. Time course of recovery following resistance training leading or not to failure. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117(12):2387-2399. doi:10.1007/s00421-017-3725-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28965198/

Santos WDND, Vieira CA, Bottaro M, et al. Resistance Training Performed to Failure or Not to Failure Results in Similar Total Volume, but With Different Fatigue and Discomfort Levels. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(5):1372-1379. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002915 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30615007/

Sampson JA, Groeller H. Is repetition failure critical for the development of muscle hypertrophy and strength?. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(4):375-383. doi:10.1111/sms.12445 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25809472/

Steele J, Endres A, Fisher J, Gentil P, Giessing J. Ability to predict repetitions to momentary failure is not perfectly accurate, though improves with resistance training experience. PeerJ. 2017;5:e4105. Published 2017 Nov 30. doi:10.7717/peerj.4105 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29204323/

Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Andersen CH, Zebis MK, Mortensen OS, Andersen LL. Muscle activation strategies during strength training with heavy loading vs. repetitions to failure. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(7):1897-1903. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318239c38e https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21986694/

Zourdos MC, Goldsmith JA, Helms ER, et al. Proximity to Failure and Total Repetitions Performed in a Set Influences Accuracy of Intraset Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(Suppl 1):S158-S165. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002995 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30747900/

Washburn RA, Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Sullivan DK, Marquis J, Herrmann SD. Resistance training volume, energy balance and weight management: rationale and design of a 9 month trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):749-758. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.002 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22446169/

Starkey DB, Pollock ML, Ishida Y, et al. Effect of resistance training volume on strength and muscle thickness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(10):1311-1320. doi:10.1097/00005768-199610000-00016 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8897390/

Roth C, Schwiete C, Happ K, Rettenmaier L, Schoenfeld BJ, Behringer M. Resistance training volume does not influence lean mass preservation during energy restriction in trained males. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2023;33(1):20-35. doi:10.1111/sms.14237 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36114738/

Mangine GT, Hoffman JR, Wang R, et al. Resistance training intensity and volume affect changes in rate of force development in resistance-trained men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(11-12):2367-2374. doi:10.1007/s00421-016-3488-6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27744584/

Peterson MD, Pistilli E, Haff GG, Hoffman EP, Gordon PM. Progression of volume load and muscular adaptation during resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(6):1063-1071. doi:10.1007/s00421-010-1735-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4215195/

Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(12):1693-1720. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4656698/

Wilk M, Zajac A, Tufano JJ. The Influence of Movement Tempo During Resistance Training on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy Responses: A Review. Sports Med. 2021;51(8):1629-1650. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01465-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34043184/

Grgic J, Lazinica B, Mikulic P, Krieger JW, Schoenfeld BJ. The effects of short versus long inter-set rest intervals in resistance training on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(8):983-993. doi:10.1080/17461391.2017.1340524 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28641044/

Mike JN, Cole N, Herrera C, VanDusseldorp T, Kravitz L, Kerksick CM. The Effects of Eccentric Contraction Duration on Muscle Strength, Power Production, Vertical Jump, and Soreness. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(3):773-786. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001675 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27787464/

Coratella G. Appropriate Reporting of Exercise Variables in Resistance Training Protocols: Much more than Load and Number of Repetitions. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):99. Published 2022 Jul 30. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00492-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35907047/

Krzysztofik M, Matykiewicz P, Filip-Stachnik A, Humińska-Lisowska K, Rzeszutko-Bełzowska A, Wilk M. Range of motion of resistance exercise affects the number of performed repetitions but not a time under tension. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14847. Published 2021 Jul 21. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-94338-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34290302/

Brandenburg JP, Docherty D. The effects of accentuated eccentric loading on strength, muscle hypertrophy, and neural adaptations in trained individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2002;16(1):25-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11834103/

Mang ZA, Realzola RA, Ducharme J, et al. The effect of repetition tempo on cardiovascular and metabolic stress when time under tension is matched during lower body exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022;122(6):1485-1495. doi:10.1007/s00421-022-04941-3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35394146/

Azevedo PHSM, Oliveira MGD, Schoenfeld BJ. Effect of different eccentric tempos on hypertrophy and strength of the lower limbs. Biol Sport. 2022;39(2):443-449. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2022.105335 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35309524/

Headley SA, Henry K, Nindl BC, Thompson BA, Kraemer WJ, Jones MT. Effects of lifting tempo on one repetition maximum and hormonal responses to a bench press protocol. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(2):406-413. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bf053b https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20351575/

Sooneste H, Tanimoto M, Kakigi R, Saga N, Katamoto S. Effects of training volume on strength and hypertrophy in young men. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(1):8-13. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182679215 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23249767/

de França HS, Branco PA, Guedes Junior DP, Gentil P, Steele J, Teixeira CV. The effects of adding single-joint exercises to a multi-joint exercise resistance training program on upper body muscle strength and size in trained men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40(8):822-826. doi:10.1139/apnm-2015-0109 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26244600/

Slater LV, Hart JM. Muscle Activation Patterns During Different Squat Techniques. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(3):667-676. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001323 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26808843/

Bourne MN, Williams MD, Opar DA, Al Najjar A, Kerr GK, Shield AJ. Impact of exercise selection on hamstring muscle activation. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(13):1021-1028. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095739 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27467123/

McCann MR, Flanagan SP. The effects of exercise selection and rest interval on postactivation potentiation of vertical jump performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(5):1285-1291. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d6867c https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20393352/

Rauch JT, Ugrinowitsch C, Barakat CI, et al. Auto-Regulated Exercise Selection Training Regimen Produces Small Increases in Lean Body Mass and Maximal Strength Adaptations in Strength-trained Individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(4):1133-1140. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002272 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29016481/

Smith E, Sepulveda A, Martinez VGF, Samaniego A, Marchetti PN, Marchetti PH. Exercise Variability Did Not Affect Muscle Thickness and Peak Force for Elbow Flexors After a Resistance Training Session in Recreationally-Trained Subjects. Int J Exerc Sci. 2021;14(3):1294-1304. Published 2021 Nov 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35096238/

Nunes JP, Grgic J, Cunha PM, et al. What influence does resistance exercise order have on muscular strength gains and muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2021;21(2):149-157. doi:10.1080/17461391.2020.1733672 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32077380/

Gentil P, Fisher J, Steele J. A Review of the Acute Effects and Long-Term Adaptations of Single- and Multi-Joint Exercises during Resistance Training. Sports Med. 2017;47(5):843-855. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0627-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27677913/

Avelar A, Ribeiro AS, Nunes JP, et al. Effects of order of resistance training exercises on muscle hypertrophy in young adult men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019;44(4):420-424. doi:10.1139/apnm-2018-0478 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30248269/

Tomeleri CM, Ribeiro AS, Nunes JP, et al. Influence of Resistance Training Exercise Order on Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Anabolic Hormones in Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(11):3103-3109. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003147 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33105360/

Costa BDV, Kassiano W, Nunes JP, et al. Does Varying Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Promote Greater Strength Gains?. J Strength Cond Res. 2022;36(11):3032-3039. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004042 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35481889/