Bench 100kg in the morning, run 10km in the afternoon. Sounds good, right? The trainee that can lift and run well earns my respect, as they have exhibited physical prowess in two disciplines, which is no easy feat. This is referred to as ‘hybrid training’, which has become increasingly popular in the past decade or so, particularly with the rise of CrossFit, Hyrox, and mixed-discipline trainees.

Hybrid training is a powerful approach that promises to blend strength with cardiovascular and endurance gains. Over the years, I’ve worked with athletes and fitness enthusiasts alike, and I’ve seen firsthand how combining these two disciplines can lead to incredible results when done correctly. Unfortunately, hybrid training is incredibly difficult to do correctly.

So, let’s dive deep into the science behind hybrid training and explore how to strike the perfect balance between lifting and running.

Understanding Hybrid Training

Hybrid training involves integrating resistance training with cardio training (e.g., running) in a way that maximises performance benefits while mitigating potential conflicts between the two. These two forms of exercise offer significant complementary benefits, yet they also place competing demands on the body.

You are effectively trying to get better at two opposite ends of the spectrum. Getting stronger, while also building your endurance.

The adaptations needed to get better at either end of the spectrum generally don’t work well together, and in fact, they often work against each other. This is known as the interference effect. It suggests that endurance training can blunt some of the strength and hypertrophy gains from resistance training, and conversely, resistance training can impact endurance performance if not structured correctly.

However, with proper planning, periodisation, and recovery strategies, it is possible to optimise both forms of training and achieve high-level results in each. This is the goal of hybrid training.

Key Benefits of Hybrid Training

Engaging in hybrid training offers a vast array of benefits beyond simply being strong and having good endurance. When properly balanced, a hybrid training regimen can:

- Improve Cardiovascular Health: Running, especially when performed at moderate-to-high intensities, significantly enhances heart and lung function. A strong cardiovascular system allows for better oxygen delivery and improved endurance, benefiting both athletic performance and long-term health.

- Increase Strength & Muscle Mass: Resistance training builds muscle, strengthens bones, and boosts metabolism. This contributes not only to athletic performance but also to improved longevity and reduced injury risk.

- Enhance Work Capacity & Recovery: Aerobic training can improve overall work capacity, meaning you can recover faster between strength training sets. A higher work capacity also allows for more effective high-volume resistance training without excessive fatigue.

- Boost Athleticism & Longevity: The combination of strength and endurance training leads to a more well-rounded and functional fitness level, reducing the risk of injuries and promoting long-term health benefits.

- Improve Metabolic Efficiency: Training in both disciplines helps optimize metabolic pathways, improving fat oxidation and glucose utilisation for sustained energy levels.

However, while these all sound wonderful, the key is to actually organise hybrid training in a way that actually works, and doesn’t lead you to burn out. To organise an effective hybrid training plan, we have to dig a little bit deeper and understand the interference effect a little bit more.

Hybrid Physiology: Conflict Between Running & Lifting Adaptations

The primary concern for lifters taking up running, or vice versa, is that the pursuit of adaptations in one domain may negate or cancel out those of the other. This is most classically reflected in the old adage of ‘cardio killing your gains’. This is the aforementioned interference effect.

Now, these concerns are not without merit, but I’d like to share with you why they may be overblown, particularly when we look at some of the early evidence that influenced this view.

A seminal study by Dr Robert Hickson (1980) examined the impact of concurrent training (strength + endurance training) on fitness outcomes in each domain. Three groups were compared, strength only, endurance only, and concurrent. However, not only did the concurrent group do both strength and endurance training, they did both training protocols without any adjustment.

What this meant was that the 6 days of endurance training were simply stacked on top of 6 days of strength training.

As we would expect, the concurrent group gained less strength (but, notably, gained the same improvements in endurance). My conclusion here would not be that performing concurrent training inherently harms strength outcomes, but rather that an excess of training volume may do so. This is especially the case in the absence of any nutritional adjustments to support this training volume (i.e. more calories).

In reality, the conflict between strength and endurance training exists on a spectrum, which has been reinforced by the research carried out over the last 50 years. It is influenced heavily by nutrition, training load in each domain, training scheduling, and other non-training factors such as stress and sleep.

So, if performing a couple of hours of cardio per week, you needn’t worry about gaining less muscle or strength, but as you move toward higher training volumes, trade-offs will occur. As a result, we first have to get very clear on what we are trying to actually achieve by hybrid training.

Setting Clear Goals

Before diving into things further, it’s essential to actually define your primary objectives. Are you aiming for overall fitness, weight loss, muscle gain, or perhaps preparing for a specific event like a triathlon?

Your goals will influence the emphasis you place on each component of your training.

- Performance Goals: If your focus is performance (say, running a faster 5K while increasing your squat) you may need to periodise your training to alternate focus areas, as these two goals may interfere more than if you were trying to run a faster 5K while improving your bench press.

- Aesthetic Goals: For those seeking a lean and muscular physique, the balance might lean more toward resistance training with supplemental running for cardiovascular health and calorie burning.

- Health Goals: If general health is the priority, a balanced approach with moderate intensities in both disciplines often yields the best long-term benefits.

Unfortunately, many discussions online about hybrid training act as if everyone has the same goal. As a result, a lot of people think that there is some singular magical hybrid training plan that they should be doing. But this is not the case. You are in charge of your goals, and the hybrid training plan is just a method to help you achieve those goals.

So you must be clear on your overall goal before you can actually design a hybrid training plan. Once you are clear on that, you can start tinkering around with crafting a plan of action. Understanding all the complexities of program design can’t be covered here, but you can look into our course on program design if you want to learn about this, or alternatively, you can read all our free exercise articles to build out your knowledge.

Managing the Interference Effect

Once you have decided on your goal(s), you need to start thinking about how you will structure your hybrid training plan. To successfully balance lifting and running, it’s crucial to structure your training to minimise the interference effect. This requires intelligent programming, prioritisation of goals, and proper recovery strategies.

1. Prioritise Your Primary Goal

Your training should be structured around your primary objective. Whether you want to maximise strength and muscle growth, improve endurance, or develop a balance between both will dictate how you allocate your training volume and intensity.

- Strength & Muscle Growth Focus: Prioritise resistance training, with running playing a secondary role in the form of lower-intensity sessions to prevent excessive fatigue.

- Endurance Focus: Prioritise running, integrating resistance training at a lower volume to maintain or slowly build strength without excessive muscle fatigue.

- Balanced Approach: If your goal is to be equally proficient in both, you’ll need a structured periodisation plan that includes alternating phases of emphasis on strength and endurance while allowing for proper recovery.

2. Structure Your Training Week

A structured training plan is essential to prevent overtraining and optimise performance in both strength and endurance disciplines. There are multiple strategies that we have in our tool box to allow us to minimise the interference effect, optimise performance and keep fatigue at bay.

- Alternating Days: One effective approach is to lift on one day and run on the next. This allows adequate recovery between sessions and helps prevent excessive fatigue accumulation.

- Same-Day Sessions: If your schedule requires training both disciplines on the same day, prioritise the most important workout first or separate them by at least 6 hours to allow for partial recovery.

- Hybrid Periodisation: Utilising periodisation cycles where training emphasis shifts in different phases (such as prioritising strength for a few weeks, followed by an endurance-focused block) can help minimise performance conflicts.

3. Optimise Workout Timing

- Run Before Lifting? If endurance is your primary focus, scheduling running first makes sense. However, avoid high-intensity running before heavy lifting to prevent neural fatigue and compromised performance.

- Lift Before Running? If strength and muscle hypertrophy are your main goals, lifting should take priority. Running afterward should be low- to moderate-intensity to avoid excessive muscle breakdown, or if it is to be high intensity, it should be relatively brief (i.e. less than 10 minutes).

- Avoid High-Intensity Back-to-Back Workouts: Two high-intensity sessions (e.g., heavy squats and sprint intervals) on the same day can lead to excessive fatigue and hinder progress. It can make sense in some cases, but it does generally dig a big recovery hole.

There is more to managing the interference effect but this should at least point you in the right direction. Now, we can get stuck into actually discussing designing your hybrid training plan.

Designing Your Hybrid Training Plan

When we discuss hybrid training, the exact specifics are obviously going to look very different, depending on the exact situation and individual we are dealing with. However, for the benefit of this article, we are going to assume we have two main tools available to us, resistance training and running.

These are the two modalities that most people tend to discuss when they are talking about hybrid training, so it makes sense to cover them. However, do realise that there are more options available to us.

With this in mind, I want to just quickly cover some of the guidelines you can use for each of these modalities, to help you organise your hybrid training plan.

Resistance Training for Hybrid Athletes

Your resistance training should generally be structured around fundamental compound movements, with volume and intensity adjusted based on your specific goals and whatever other endurance training you are doing. Key guidelines include:

- Primary Lifts: Squats, deadlifts, bench presses, overhead presses, chins and rows should form the foundation of your strength training.

- Accessory Work: Single-leg exercises, machine movements, and lighter work can be used to fill in the gaps, and improve the stability of certain joint structures.

- Training Volume: 2-4 sessions per week, with moderate volume (3-5 sets of 4-8 reps), and generally 2-3 reps in reserve (RIR) to build strength without excessive fatigue.

- Power & Speed Work: Plyometrics, sled pushes, and explosive lifts can enhance athleticism and running efficiency, and it does generally make sense to include this stuff with your resistance training.

Running Training for Hybrid Athletes

Your running program should complement your strength work to avoid excessive fatigue while improving endurance. Consider the following:

- Base Training: Easy, low-intensity, zone 2 runs to build an aerobic foundation without interfering excessively with recovery.

- Speed Work: Sprint intervals, tempo runs, and hill sprints to develop anaerobic power and running efficiency.

- Long Runs: Strategic scheduling of longer runs (10K+) on days separate from heavy lifting sessions.

Again, there is more to this, but these guidelines should give you a starting point.

Scheduling: How to Optimally Schedule Running & Lifting Workouts

There will inevitably be some crossover between running and lifting workouts, with fatigue from one potentially being of detriment to the other. This can be minimised through smart scheduling throughout the week, but before we get to that, I want to make one thing very clear:

Building fitness is not the same as testing fitness.

You don’t need to be at your best during every workout. If your legs are a little tired from your lifting session and you have to slow your running pace by 10-20s per km, that is okay. It would not be okay if you were testing (i.e. racing), but this is just training. When we train, we seek adaptations that will allow us to perform better in future, and thus we needn’t worry about small deviations in performance.

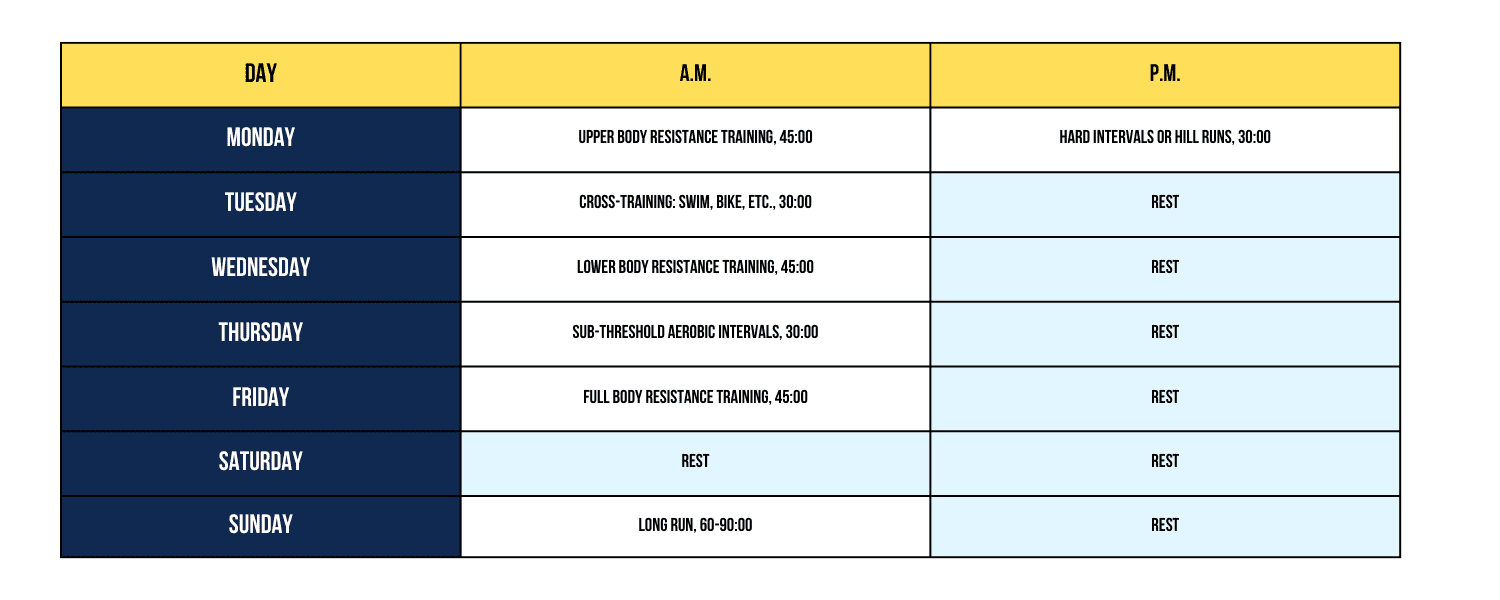

With that said, that doesn’t mean scheduling and crossover fatigue doesn’t matter. Doing your hard interval runs right after a hard leg day isn’t very smart if you’re trying to maximise output during those runs, and vice versa if you have a heavy leg day to tend to. What we can do instead is lay out the sessions for each modality and assess which have the greatest crossover.

Lower body resistance training + hard interval run = high crossover.

Lower body resistance training + light run = moderate crossover.

Upper body resistance training + any running = low crossover.

Sessions with the highest crossover should be spread out most within the week, whereas those with low crossover can easily be performed back-to-back, even on the same day. Let’s see how that might look when applied to a training week. We will use the example of an Upper / Lower / Full Body training split to illustrate this.

This is just one example of applying these principles in practice. There is no one ‘best’ way, but if you follow the basic principle of spreading sessions out in accordance with their crossover, you will be well on track. When performing back-to-back sessions, there are some considerations related to the molecular signals of each mode of activity.

As alluded to previously, endurance training increases AMPK activation, which may compromise the response to resistance training. AMPK remains elevated for approximately 3 hours after high-intensity endurance training, and thus resistance training should be performed at least 3 hours after, but preferably longer (e.g. morning and evening).

However, for low intensity aerobic sessions, this is not as much of a concern (e.g. light shake-out run, bike work, or swim), and the performance of resistance training after this may even enhance the aerobic training stimulus, without compromising strength. The AMPK & MTOR relationship is complex, and this is something we cover in a lot more detail in our Nutrition Certification.

One final note on this is that you should consider your current strengths when deciding on scheduling. For example, if a seasoned runner was adding in lifting, then I might encourage them to schedule in such a way as to optimise gym performance, or vice versa for a lifter getting into running. Therefore, in such a situation, I would suggest training your weaker activity first (e.g. if doing both on the same day).

Scheduling Strategies

With the above in mind, you effectively have 3 different scheduling strategies to choose from:

- Separate Days: One effective method is to dedicate separate days to lifting and running. For example, you might lift on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and run on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. This separation generally allows each system to recover quite well, although it can be tricky when integrating sprints, longer runs and lower body training.

- Same-Day Training: If you must do both on the same day, consider splitting sessions (e.g., running in the morning, lifting in the evening, or vice versa) and try to prioritise the session that aligns more with your primary goal.

- Interval Integration: Some athletes integrate running intervals or HIIT sessions into their strength workouts, but this requires careful management to ensure quality in both training modalities.

Now, before you use some combination of these to design your workout, you do want to also factor in rest days. It is generally a good idea to include at least one full rest day per week. Active recovery, like light yoga or walking, can also help maintain flexibility and circulation.

Periodisation: How to Periodise Running & Lifting Around Competition

Your training schedule does not have to remain the same throughout the year. In fact, I would suggest varying it regardless, even if you don’t compete. I will often suggest periods of focus during the year for my clients, regardless of whether or not they have a ‘real’ competition or race.

Let’s take the example of a seasoned lifter who wants to pack on as much muscle as possible during winter, but also has the goal to compete in a half-marathon in the summer.

Spring: 40% Running, 60% Lifting

Summer: 60% Running, 40% Lifting

Autumn: 50% Running, 50% Lifting

Winter: 30% Running, 70% Lifting

By varying training load in this way, you can focus on maximising adaptations during a given period of time in one modality, rather than always trying to balance the two. The irony in ‘balancing’ two activities is that it’s best applied in an imbalanced way, but the balance emerges over time through adaptations from your well-periodised training plan.

For those who have spent most of their training career lifting, this is often difficult to accept. To overcome this psychological barrier, remember that it takes a lot less to maintain what you have built than to build it in the first place. This also applies to running. If you are dropping from 5 days of lifting to 3 days (60% baseline), you’re likely to still maintain muscle and strength, even if it doesn’t feel like much compared to what you’ve been used to.

This approach can be very psychologically liberating, and makes for far more enjoyable training. Rather than just being 50/50 all the time, you can now dedicate your focus to one modality while allowing the other to drop back a bit, nonetheless reassured that you are going to maintain most of your gains. In my experience as a coach, this promotes far better longevity for hybrid athletes who wish to maintain 2 or more sports or activities over the long term.

Periodisation: The Key to Success

Periodisation is crucial in hybrid training to avoid overtraining and ensure optimal progress in all areas. To put it into practice, consider the following:

- Macrocycles: Define your long-term training goals over several months.

- Mesocycles: Break down your macrocycle into phases that focus on either strength, endurance, or a mix.

- Microcycles: Plan your weekly workouts with specific sessions for lifting and running, with specific goals and rationale for each session.

Adapting Your Program Over Time

Designing a balanced hybrid program isn’t a one-and-done process. Your body will change, your goals may shift, and life circumstances can also evolve. The reality is that you are also unlikely to design the perfect hybrid program on your first try. You will have to tweak it over time, and tailor it to your specific needs. So understanding how to adapt your program is essential. Below are strategies to help you adapt, progress, and keep your training both productive and enjoyable.

1. Listen and Adjust

If you want to get the most out of your program, then you will need to develop the skill of listening to your body. This is something that takes time to develop, but once you are able to listen to the signals your body is giving you, you will be able to tweak the program to your needs.

Performance Metrics

- Track Strength Gains: Keep an eye on your personal bests in the gym (e.g., squat, deadlift, bench press). If you notice your numbers are plateauing or declining, it might be time to adjust your routine, either by tweaking volume, intensity, or exercise selection.

- Monitor Endurance: Pay attention to your running times, distances, and how you feel during and after each run. If your pace is slowing or you’re struggling to hit mileage goals, assess whether you’re recovering adequately or if you need to lighten the load.

Recovery Status

- Assess Soreness & Fatigue: Feeling excessively sore or constantly tired could be a sign you’re pushing too hard. Consider adding more rest days, reducing overall volume, or introducing more active recovery sessions.

- Prioritise Restful Sleep: Recovery is closely tied to the quality and quantity of your sleep. If your progress stalls and you’re feeling run-down, evaluate your sleep habits first before making drastic changes to your training plan.

Feedback

- Coaching & Training Partners: A coach or knowledgeable training partner can offer another perspective on how you are progressing. You may not have someone like this in your corner, so it can be difficult, but social media may also be another avenue to connect with people that may be able to offer your thoughts on how you are progressing and where you may need to adjust things.

- Self-Assessment: Alongside external feedback, you can practice honest self-check-ins. How do you feel mentally and physically at the end of the week? Are you still looking forward to your workouts, or do they feel like a chore? Do you feel like you are progressing adequately?

With all of this data, you will be able to adjust and refine your plan. Maybe you need a little more rest days. Maybe you need a bit more resistance training, or cardio. The plan will need to be refined slowly over time.

2. Avoid Excessive Training Volume

With hybrid training, it is very easy to fall into the trap of just doing more. But the focus should be on quality over quantity. Just because you have multiple goals doesn’t mean you have to do excessive amounts of work to achieve them. You also don’t need to jump in at the very top end of volume, and instead, you should build it slowly over time.

- Focus on Form & Technique: It’s easy to get swept up in doing more sets, more miles, or more workouts. However, prioritising quality means ensuring each lift is performed with proper technique and each run is executed with good form.

- Strategic Volume: If you’re noticing diminishing returns or increased injury risk, reduce your weekly sets or cut back on running mileage. Adaptation occurs when you challenge your body just enough to spark improvement, but too much can lead to overuse injuries and burnout.

- Scheduling Deliberate Recovery: Make sure you’re scheduling rest days or lighter training blocks. Giving your body room to recover is just as important as the hard workouts themselves.

This is something you are going to have to deal with a lot with hybrid training. You will likely teeter on the edge of doing too much training volume quite a bit.

3. Progressive Overload

You aren’t going to get better if you just do the same stuff over and over. Your training needs to get more challenging over time if it is to lead to the results you want. Adapting your program over time so that it is progressively more challenging, while not pushing things into the “too challenging” territory, is always difficult. But you will need to progressively overload if you are to achieve the goals you want to achieve.

Resistance Training

- Gradual Weight Increases: A proven way to build strength is to slowly add weight to the bar. Small increments, over time, can pay big dividends.

- Vary Reps and Sets: If upping the weight isn’t feasible every session, consider additional sets, adding reps, or increasing the time under tension to challenge your muscles.

Running

- Increase Mileage Carefully: A common guideline is to increase weekly mileage by about 10% until you reach your desired mileage to reduce the risk of injury. However, when trying to also include a lot of resistance training, a smaller weekly increase (e.g. 5%) may make more sense.

- Incorporate Speed Work: Fartlek, interval training, or tempo runs can challenge your cardiovascular system in different ways and enhance overall performance.

- Hill Training: Adding hills to your runs can build leg strength and improve running economy without necessarily adding excessive mileage.

These tips should help you to adapt your program over time, but it can still be difficult. If you want to learn more about all this exercise stuff, then we would recommend our free exercise content or our program design course.

Recovery & Nutrition Strategies

Finding the right balance between resistance training and running can be a rewarding but challenging endeavour. Your body faces unique demands from both activities, which is why a robust recovery strategy is critical. So I just want to touch on how to optimise recovery and nutrition so you can perform at your best in both the weight room and on the road (or trail).

1. Prioritise Sleep & Stress Management

- Get Enough Sleep (7-9 Hours): Think of sleep as your superpower. During deep sleep, your muscles repair, hormones rebalance, and your mind recharges. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality shut-eye each night. If you can, establish a calming bedtime routine (like reading a book or practising gentle stretching) to help you wind down.

- Manage Stress Through Mind-Body Activities: When you’re juggling intense running sessions and heavy lifts, stress can accumulate quickly. Activities like yoga, meditation, or even simple breathwork not only help relax your mind but also aid in muscle relaxation and recovery. Mobility sessions can serve the dual purpose of easing tension and improving flexibility.

2. Nutrition for Hybrid Athletes

To effectively fuel and recover from your training sessions, you will have to have your nutrition dialled in. You can read up more about fundamental nutrition practices here, but I want to just touch on a few important points related to nutrition for hybrid trainees below.

Protein Intake

- Support Muscle Repair: Since you’re asking your body to build strength and endure long runs, protein is essential. Try consuming around 2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

- Spread It Out: Distribute your protein intake throughout the day (think protein in every meal or snack) to continually supply muscles with amino acids.

Carbohydrates

- Fuel for Running: Carbs are your primary energy source for those challenging runs. Incorporate complex carbohydrates (like whole grains, oats, and potatoes) into your meals, especially around workout times. This ensures your energy levels remain steady. Your calorie intake will likely need to be quite high, and carbs should make up a large part of this.

- Timing is Key: Eating carbs before a run gives you the energy to power through, while consuming them afterward helps replenish glycogen stores in your muscles, speeding up recovery.

Fats

- Essential for Hormone Production: Healthy fats (think avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil) play a role in hormone regulation, which can impact recovery, mood, and overall health. Don’t be afraid to include them in your daily meals.

- Longer Energy Source: Fats also provide a sustained source of energy, especially useful for longer or slower runs.

Hydration

- Stay Hydrated: Both lifting and running can be dehydrating, especially if you’re sweating a lot or training in hot conditions. Make sure you’re drinking enough water consistently throughout the day.

- Electrolytes Matter: During longer runs or intense lifting sessions, consider sports drinks or electrolyte tablets to replace sodium and other minerals lost through sweat.

3. Recovery Protocols

Recovery is a relatively passive process, at least from the perspective of what you have to do. However, there are certain things you can do to help move things in the right direction.

Active Recovery

- Light Movement, Big Benefits: On your rest days, gentle activities (like easy cycling, casual swimming, or a relaxed walk) can help increase blood flow to tired muscles. This can flush out metabolic waste (like lactic acid) and reduce soreness, setting you up for your next workout feeling fresher.

Mobility & Flexibility Work

- Prevent Injuries & Improve Performance: Taking time for stretching, foam rolling, or using mobility tools helps loosen tight muscles and maintain flexibility. This not only prevents injuries but also ensures you can maintain proper form during both running and lifting.

Deload Weeks

- Strategic Rest: Every 4-6 weeks, scale back your training intensity or volume. This is your body’s chance to more fully recover and adapt to the stresses you’ve been placing on it. You’ll come back stronger and more mentally refreshed, reducing the risk of overtraining or burnout.

The Importance of Recovery

Remember, training is only half the equation, recovery is where the real magic happens and you actually adapt to the training and get better. By giving your body the time and resources it needs to rebuild, you’re setting yourself up for long-term progress.

- Sleep: We can’t emphasise it enough: 7-9 hours of quality sleep is vital for muscle growth, hormone balance, and mental resilience.

- Active Recovery: Non-intense movement on rest days can speed up recovery and help maintain a healthy routine without adding too much strain.

- Mobility Work: Regularly incorporating stretching, foam rolling, and dynamic warm-ups not only aids recovery but also keeps your joints and muscles in top condition to handle both the squat rack and the running track.

Balancing lifting and running is an endeavour that demands respect for both forms of exercise and the critical role of recovery. By prioritising sleep, managing stress, fueling your body with the right macronutrients, and incorporating smart recovery methods, you’ll actually facilitate the development of both strength and endurance.

Common Pitfalls and How to Overcome Them in Hybrid Training

Hybrid training can be highly effective but also presents unique challenges. Avoiding the common pitfalls will allow you to make consistent progress, and actually achieve your goals.

1. Overtraining

Overtraining occurs when the body is pushed beyond its ability to recover, leading to chronic fatigue, declining performance, and increased susceptibility to illness and injuries. This is particularly common in hybrid training.

How to Prevent Overtraining:

- Monitor Your Body: Keep a training journal or use a fitness tracker to log workouts, energy levels, and signs of fatigue. If performance starts to decline or you feel constantly fatigued, it’s time to reassess your workload.

- Listen to Your Body: Persistent soreness, disrupted sleep, or a decrease in motivation are all warning signs. If you feel overly fatigued, schedule a deload week or an extra rest day.

- Balance Training Volume: More is not always better. Focus on quality over quantity, ensuring each session serves a purpose rather than simply accumulating training hours.

- Prioritise Recovery: Adequate sleep, hydration, and proper nutrition support muscle repair and energy replenishment. Recovery techniques such as foam rolling, contrast baths, and massage can also be beneficial.

2. Conflicting Adaptations (Interference Effect)

The “interference effect” occurs when adaptations from one type of training (e.g., endurance) negatively impact another (e.g., strength). This is because strength training predominantly relies on fast-twitch muscle fibres and neural adaptations, whereas endurance training builds slow-twitch fibre efficiency and cardiovascular endurance.

How to Minimise the Interference Effect:

- Prioritise Your Goals: If strength is your main goal, structure your program so that heavy lifting is not compromised by endurance work. If endurance is the focus, then prioritise it in your programming.

- Optimise Timing: Spacing training sessions appropriately can reduce interference. Ideally:

- Separate strength and endurance sessions by at least 6 hours (morning/evening).

- On days where both are performed, it is generally best to do strength training before endurance training to allow for high power output.

- If possible, schedule them on different days.

- Use Smart Periodisation: Avoid trying to push endurance volume while also trying to push resistance training volume in the same cycle. Instead, align focus on pushing one while the other is on maintenance.

3. Increased Injury Risk

Hybrid training increases stress on muscles, joints, and the nervous system, leading to higher injury risks. This is especially true when combining heavy weightlifting and high-impact endurance work (e.g., sprinting, long-distance running).

How to Prevent Injuries:

- Warm-Up and Cool-Down: Always perform dynamic stretches, mobility drills, and sport-specific warm-ups to prepare the body. After workouts, include a proper cool-down routine to aid recovery.

- Master Form and Technique: Poor lifting mechanics or improper running form increases injury risk. If unsure, consider working with a coach or watching high-quality tutorials.

- Gradual Progression: Sudden spikes in training volume or intensity increase the likelihood of overuse injuries. Follow the 10% rule, don’t increase training load by more than 10% per week. Ideally, it would even be lower than this, unless you know your body well and have experience.

- Listen to Pain Signals: Pain is an early warning sign. Ignoring it can lead to chronic issues. Take rest days, cross-train, or modify workouts as needed.

4. Ignoring Recovery

Underestimating the importance of recovery can stall progress and increase injury risk. Since hybrid training demands more from the body, recovery strategies must be intentional.

How to Maximise Recovery:

- Prioritise Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night to support hormonal balance, muscle repair, and performance.

- Dial in Nutrition: Ensure the general diet is dialled in, with a large focus on eating sufficient calories and protein. Stay hydrated and consume electrolytes, especially after long endurance sessions.

- Incorporate Active Recovery: On rest days, opt for activities such as mobility work, stretching, yoga, or light swimming to enhance circulation without adding significant stress.

- Schedule Deload Weeks: Every 4-6 weeks, reduce intensity and volume to allow for full-body recovery and prevent burnout.

5. Excessive High-Intensity Training

Too much high-intensity work (e.g., heavy lifting, sprints, HIIT) can lead to burnout, hormonal imbalances, and plateaued progress. While intensity is crucial, balancing effort levels is key.

How to Balance Intensity:

- Follow the 80/20 Rule: 80% of training should be at low to moderate intensity, while 20% should be high-intensity. This ensures cardiovascular and muscular adaptations without overloading the system.

- Plan Recovery Days: Don’t stack multiple high-intensity sessions in a row. Alternate heavy training days with lower-intensity sessions.

- Use Heart Rate Monitoring: If you’re constantly training in the high-intensity zone, consider adjusting workloads to avoid excessive strain.

Hybrid training is a powerful approach, but it requires careful planning to maximise results while avoiding setbacks. By prioritising smart programming, recovery, and injury prevention, you can successfully balance strength and endurance training while maintaining long-term health and performance.

Hybrid Training Summary

You can get fitter and stronger at the same time. You can run further and build more muscle. Don’t listen to the nay-sayers. This is exactly what I help my clients achieve with our coaching service. With that said, I don’t want you to get carried away with what I am saying either.

If you want to be the best runner you possibly could be, or the best bodybuilder you could be, you do have to accept trade-offs. Phil Heath (arguably the greatest bodybuilder of the 21st century) could not transform into Eliud Kipchoge (arguably the greatest runner, albeit challenged now by Kiptum!), nor could Kipchoge get up on the Olympia stage.

But, for those of you who’d like to run a 10k and maybe even a marathon every now and then, while still wielding a decent physique on the beach or benching your body weight, this is very achievable.

If you need help with your own training, you can always reach out to us and get online coaching, or alternatively, you can interact with our free content, especially our free exercise content.

If you want more free information on nutrition or training, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

References and Further Reading

Hickson RC. Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1980;45(2-3):255-263. doi:10.1007/BF00421333 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7193134/

Wilson JM, Marin PJ, Rhea MR, Wilson SM, Loenneke JP, Anderson JC. Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2293-2307. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22002517/

Baar K. Using molecular biology to maximize concurrent training. Sports Med. 2014;44 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S117-S125. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0252-0 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4213370/

Wang L, Mascher H, Psilander N, Blomstrand E, Sahlin K. Resistance exercise enhances the molecular signaling of mitochondrial biogenesis induced by endurance exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;111(5):1335-1344. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00086.2011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21836044/

Coffey VG, Pilegaard H, Garnham AP, O’Brien BJ, Hawley JA. Consecutive bouts of diverse contractile activity alter acute responses in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;106(4):1187-1197. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91221.2008 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19164772/

Hickson RC, Rosenkoetter MA, Brown MM. Strength training effects on aerobic power and short-term endurance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12(5):336-339. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7453510/

Nelson AG, Arnall DA, Loy SF, Silvester LJ, Conlee RK. Consequences of combining strength and endurance training regimens. Phys Ther. 1990;70(5):287-294. doi:10.1093/ptj/70.5.287 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2333326/

Murlasits Z, Kneffel Z, Thalib L. The physiological effects of concurrent strength and endurance training sequence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(11):1212-1219. doi:10.1080/02640414.2017.1364405 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28783467/

Lundberg TR, Fernandez-Gonzalo R, Tesch PA, Rullman E, Gustafsson T. Aerobic exercise augments muscle transcriptome profile of resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310(11):R1279-R1287. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00035.2016 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27101291/

Mathieu B, Robineau J, Piscione J, Babault N. Concurrent Training Programming: The Acute Effects of Sprint Interval Exercise on the Subsequent Strength Training. Sports (Basel). 2022;10(5):75. Published 2022 May 10. doi:10.3390/sports10050075 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35622484/