Understanding the goals of nutrition is actually quite helpful for helping you to better allocate your limited resources. We talk about good nutrition as if there is a singular goal for nutrition, and this just isn’t the case. There are multiple goals of nutrition, and while these goals often have significant overlap in the specific nutrition practices required to achieve them, they often also have significant differences.

So it is important to be clear on what your exact goals are with nutrition, and the only way to do that is to understand what the broader goals of nutrition are. When coaching people, we very often spend a decent chunk of time at the start of the process, getting really clear on their goals. However, to then translate their goals into an actionable plan, we have to also be clear on what the goals of nutrition are. So, to do this, we have to be clear on what goals of nutrition are.

Before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Table of Contents

The Main Goals Of Nutrition

Everyone and their grandmother have some idea of what good nutrition actually is, and if I asked 100 people to choose “healthy foods”, everyone would agree on about 90% of the food choices. But how do we know what good food is? How do we even decide that? Not just from a daily life point of view, but even from a scientific point of view?

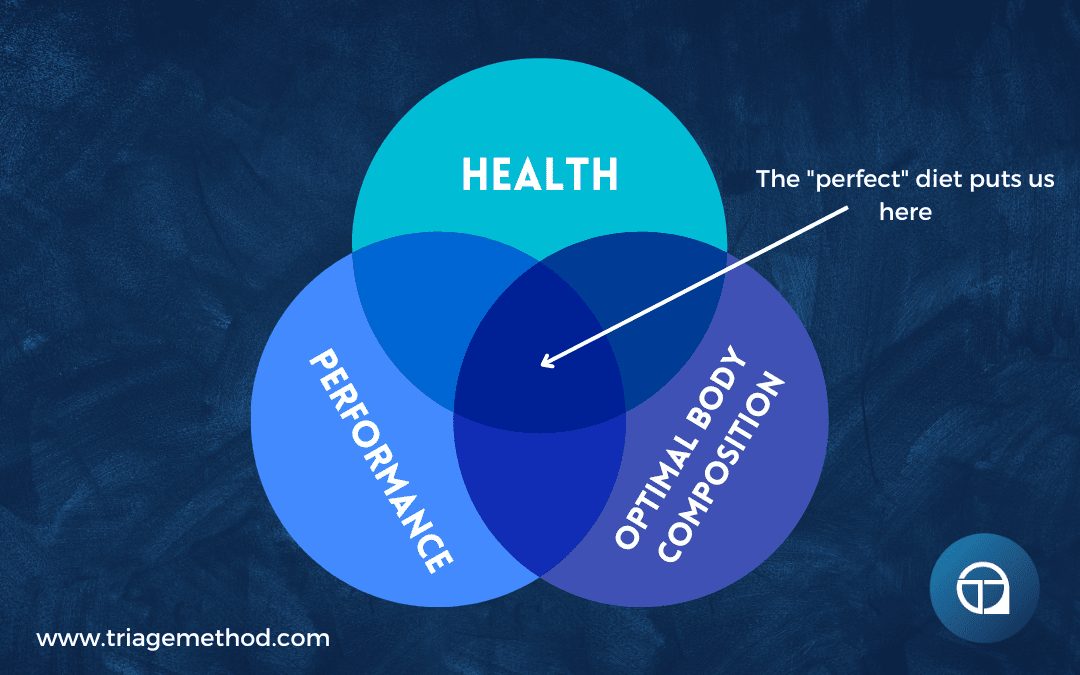

Well, we at Triage believe that a good diet should give you three things;

- Health

- Performance

- Your Optimal Body Composition

These are what you could call the three main goals of nutrition.

Now, in an ideal world, a “perfect” diet would help us to accomplish all three of these and we would find ourselves slap-bang in the middle of the intersection of all of these. However, quite a few, perhaps even most, diet strategies very often prioritise chasing one of them at the expense of one or even two of the other goals. It is understandable why this happens, everyone wants results yesterday after all. It’s unfortunately the world we live in now. However, the increased focus on achieving one of the goals very often compromises the others.

“Want to get really lean really quick? Eat this meal replacement food (that I sell for a huge profit) and follow this 800-calorie diet”, you will hear one salesman, sorry I mean fitness professional say. Never mind that the diet leaves you with no energy to get your work done throughout the day, your relationships are suffering as a result, your hair has started falling out from the lack of nutrition, your body is starving, your health is failing, your hormones are out of whack, your sex drive is in the toilet etc. etc. No, no, no, none of that matters, because you look great on the beach. You got that 6 pack you always wanted, yeah it compromised your health, but I mean you look good in the photos? You finally got the girl/guy you always wanted so the diet was a success, it doesn’t matter that you have no sex drive now and don’t want to do what couples do because you got that 6 pack!

I hope you can sense the sarcasm in my words.

However, it’s not only limited to people gunning for aesthetics and compromising their health and performance (both mental and physical) in the process. You will often see people obsess over eating the best whole foods, they eat only the best organic free-range non-GMO produce available to them, but they are still compromising their health because they are overweight because they have no knowledge of calorie balance. They are likely looking after their health to some extent (although being overweight is a cardiovascular risk factor) and their performance likely isn’t that bad, but their body composition isn’t optimal for them.

So let’s define these terms so we are all on the same page.

Health is defined as the absence of disease, traditionally at least. I don’t know about you but I want to think of health as more than the absence of a state of disease. I want to feel as good as possible, I want my blood work to be perfect, and I want to radiate vitality. That is health. We can boil it down to numbers and figures on a page, but it is as much a mental as it is a physical state. We generally think of health as resilience to and against insults to your life and well-being.

Performance is both physical performance and mental performance. You should be able to do whatever you wish with your body. Need to run for the bus? You should be able to. Want to play with the kids? Need to lift up that heavy box? You should be able to. Your body should be able to perform in the ways you need it to, to make life easy for you. But so should your mental performance. You shouldn’t be feeling tired/dull or foggy-brained as soon as 3 o’clock rolls around. You should feel mentally astute all day. You should be waking up in the mornings with both mental and physical vigour. That’s what good performance is.

Your optimal body composition is the level of body fat and musculature that both allows you to feel and perform at your best, and also allows you to feel sexy and confident when you look in the mirror. People like hard and fast rules (you should be X% body fat) and we will give you a rough guide later in this article series, but these are just very rough guidelines and aren’t specific to you as an individual. Optimal body composition is not something we define for you, it’s the optimal body composition that leaves you with the physique and health that you desire.

So when we think about dieting we want to think in an outcome-based manner. We want our diet to be based on the outcomes we see before us. Not on some theoretical result. The actual results we see from the dietary adjustments we make.

If our dieting strategies aren’t working, something needs to change. As has been discussed, there is no one-size-fits-all diet, but to complicate matters further, dieting strategies that worked for you in the past may not work for you now. Your metabolism is in a constant state of change based on your activity levels, your body fat levels, and muscle mass levels (and other factors).

So, effectively, the three main goals of nutrition are:

- Support health.

- Fuel your activity and performance.

- Support optimal body composition.

Support Health

As we discussed in the last article in this series on why nutrition is important, your diet does profoundly affect your health. Many health issues and diseases can be prevented, treated and/or see improved symptom management with health diet practices. So it is fairly intuitive that one of the main goals of nutrition is to support health.

This will obviously look different depending on what exactly you mean by health and what you are optimising for. But for most people, this will mean that you are consuming an appropriate amount of calories for your body and activity levels, along with consuming at least the minimum amounts of each of the macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, fats and fibre (most people are underconsuming protein and fibre)) and micronutrients (this generally doesn’t need to be micromanaged if you eat a diverse and varied, predominantly whole foods diet).

Most people will also want to eat a heart healthy diet, as heart disease is one of the biggest killers of humans. This generally means eating a diet that is relatively low in saturated fat (less than 10% of calories), high in fibre, and low in sodium. Staying at a health body fat level and eating a diet that is anti-inflammatory in nature also help.

The diet can also be used to support overall metabolic health, and good metabolic health is foundational to preventing, reversing and/or supporting many health issues. This generally means eating a balanced diet rich in whole foods, such as vegetables, fruits, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Prioritising foods that are high in fibre and low in refined sugars can help to regulate blood sugar levels and support metabolic health. Staying at healthy body fat levels is also important, which generally means eating a calorie appropriate diet. Exercise, sleep and stress management do also all play a role in metabolic health too. Together, these practices can significantly enhance metabolic health, reducing the risk of metabolic disorders like diabetes and obesity.

Beyond this, you can tailor your diet practices to help tackle whatever specific issue(s) you are dealing with. Getting the foundational healthy diet habits in place will allow you to go quite far with dealing with specific issues, but you may still need to dial the diet practices in to the specific issue. This is obviously beyond the scope of this article, as there are countless issues we could potentially discuss. But it is important to just be clear on what you mean by health, and to then tailor the diet to support that.

We already covered a lot about nutrition and health in the last article, so I won’t belabour the point here. Now, supporting health is only one of the goals of nutrition though, there are other goals!

Fuel Activity and Performance

Fuelling activity and performance is another goal of nutrition. This one shouldn’t be too hard to intuitively grasp, because most people are aware that we get energy from food. So if you don’t eat food, you won’t be fuelling your activity adequately and you will likely see poorer performance as a result.

While this should be intuitively obvious enough, most people do not eat in a way that adequately fuels their activity and performance. Even athletes who you think would be more incentivised to really dial their nutrition in to support their performance, unfortunately, very often don’t optimise their diet for their needs.

What this looks like will obviously be different depending on the exact population and individual. The needs of an office worker are going to be different than the needs of someone who is very active all day in their job like a nurse or manual labourer, and the needs of an athlete are going to be different again. But there are some common mistakes we can learn from, that apply to many situations.

Not eating throughout the day is probably the biggest problem for fuelling activity and performance. This can be due to a variety of reasons, but the end result is the same. Poor fuelling and poor performance.

Many people will not eat sufficiently throughout the day and effectively save a lot of their food intake for later in the day, and as a result, end up poorly fuelling their activity for the day. This usually results in them doing less activity overall (and thus burning fewer calories). It also results in poorer performance, both physical and cognitive. So any exercise they do engage in is not their best effort. They also perform poorly in any cognitively demanding tasks throughout the day, and in the increasingly cognitively demanding working world we live in, this likely just results in poorer work performance.

As a further aside, it does also generally result in poorer “emotional performance” across the day too. Most people are not at their best in terms of their emotional regulation and expression when they are in a state of poor fuelling.

Not eating all day and then eating a lot at night is like putting your phone on flight mode and power saving mode all day to conserve energy. You can get through the day with it like this, but it won’t work optimally and your capabilities will be limited.

Not eating much all day can be intentional or unintentional, and I will go through a few cases to show you why this happens and how it affects things. However, having coached many people, very often it is just poor planning that causes this to occur. I have had multiple clients with extremely busy schedules that don’t allow for much food intake throughout the day (for example nurses). So for them to fuel adequately, we have to come up with better strategies that allow for better fuelling across the day. This usually means being more diligent with fuelling before work (i.e. having a real meal before work, not just something on the go as they rush out the door) and despite very often hectic schedules, there are usually some opportunities to get food in if you actually have a plan for it (for example, having a protein shake and some fruit takes 30 seconds). There are some circumstances where it is genuinely very difficult to fuel adequately (for example a surgeon may be in surgery for hours at a time) but these are generally in the minority, and it is not the same thing as someone who frequently wakes up late and skips breakfast as they rush out the door because they are “too busy”.

Failing to fuel effectively across the day, and going large portions of the day without food generally just results in poorer food choices across the day too. You have more than likely been in a situation where you either skipped breakfast or had only a small bite to eat, and then couldn’t get your next meal until later than you had anticipated. Usually this either results in snacking on poor quality foods (eg biscuits and sweets) if they are easily available, or it results in overeating at lunch or the evening meal. We ideally don’t want to set up our life in a way that leads to excessive consumption of poorer quality foods, or excessive consumption of food. So going long portions of the day is less than ideal, and given that it also leads to poor performance across the day, we really want to avoid this if possible.

Now, some people will suggest that fasting or going longer periods of time without eating actually improves their cognitive performance. However, this is generally not the case. I am sure for some people it may improve their cognition, however, for the vast majority of people, this is just a case of falling for feelings over facts. Not eating tends to lead to an increase in excitatory hormones, as they try to mobilise stored fat and provide you with energy to go out and seek food. So fasting or not eating can lead to you feeling a bit more “buzzed” and many people mistake this for improved performance. But it generally does not lead to improved performance compared to actually eating before cognitively demanding tasks. You can trial this yourself by doing some form of cognitive testing in a fasted state and in a fed state, and for most people, performance is dramatically improved in the fed state.

This doesn’t mean you can’t use some degree of strategic fasting, if you do find it improves your ability to actually start a task and do it. But you just have to be clear in your actual goals and language. You are not improving your performance by fasting, you are just making yourself feel like you are performing well.

Not eating enough overall is also a big issue when it comes to fuelling activity and performance. Unfortunately, many people drastically under-fuel themselves and see a decrease in their activity levels and performance. We see this a lot in our coaching practices, especially as Brian is an expert in disordered eating and helping people recover from issues such as this.

Many clients have concerns about eating more to fuel performance, thinking that it will interfere with their aesthetic goals but often end up engaging in binge eating behaviour as a result.

In this binge-restrict cycle, they end up eating more anyway, but it’s quite distressing for them. In the process of doing nutrition coaching combined with Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), we work to resolve eating problems like bingeing and also the (often) body image concerns that drive these behaviours in the first place that can perpetuate under-eating.

A lot of people under consume calories in the pursuit of fat loss, and see their physical and cognitive performance decrease. This is a little bit more obvious in athletes, and women in particular, as they see either a measurable decrease in their performance or they see the effects by virtue of losing their period. However, it does affect everyone. In sports, there is a term for it, RED-S. Which stands for “relative energy deficiency in sports” (it used to be known as female athlete triad), but the same effects can be seen in the average person who is deficient in energy.

We see a lot of people come to our coaching practice in a situation where they aren’t as lean as they want to be, and they are seeing a decrease in their performance due to undereating in the pursuit of fat loss. Usually, they are finding it very difficult to lose fat because their activity levels have dropped dramatically due to being in a deficit for so long (we will discuss metabolism and how this occurs in a later article in this series, but right now, you may find the following article on eating more to lose fat interesting). They very often don’t realise it, but their day to day work and life performance has likely also dropped. Sure, they notice the lack of energy throughout the day, but they don’t actually realise how much less productive they are as a result of under-fuelling.

Unfortunately, a lot of people find themselves in a situation where they are actually getting the worst of all worlds. They eat very little during the week, see performance decrease, but then don’t see the fat loss they want, because they end up over-eating on the weekend. This is one of the most frustrating places to be in, because you are getting all of the downside with none of the upside.

Fortunately enough, this can all be fairly easily solved by getting the diet right. This is why it is important to realise that fuelling activity and performance is one of the main goals of nutrition. It really does impact the way you view your nutrition and diet overall.

However, it isn’t just eating too little that can impact activity and performance. So too can eating too much. This is probably most obvious when viewed over the longer term. If the over-consumption leads to excessive weight gain (especially fat gain), then activity levels and performance may be negatively impacted. This isn’t always the case, as sometimes weight gain, and even fat gain, can actually be beneficial for performance and the added calories can lead to increased performance. But there is generally a point where continued excessive intake leads to excessive weight gain, and a decrease in activity levels and poorer performance.

Eating too much can also lead to poor performance in the short term too. Most of you have likely had a large meal and then felt extremely sluggish afterwards. This is due to digestion being a largely parasympathetic activity (the rest and digest side of the nervous system). So it makes sense that a large meal would make you feel quite sluggish and decrease performance as a result.

Now, it isn’t all just about calories and the energy part of the nutrition equation. The quality of your food also matters for fuelling performance and activity. Depending on the exact specifics, there are going to be better or worse macronutrient ratios for a given goal. We will be discussing this in later articles in this series, so I won’t get into it here. However, I do just want to note that eating a poor quality diet, that consists of stuff like processed foods and confectionaries, generally is not best for fuelling activity or performance. There are situations where someone like an athlete may need to rely on very quick digesting sources of carbohydrates, and poorer quality foods can be used for this. But in almost all cases, eating a poorer quality diet results in reduced performance.

I know I said I wouldn’t discuss macronutrients here as we will be discussing them later on, but I think the following bears noting as it is quite common. Most of you have likely eaten a high carbohydrate meal and then felt tired afterwards. This can be due to a variety of factors, but very often it is due to eating a high carbohydrate meal with very little fat or protein. This then leads to poor blood sugar regulation, and swings between high and low, which leads to variable energy levels. So, the macronutrient composition of your meals does matter.

It also isn’t just the calorie and macronutrient content of the diet that affects energy levels and performance. Dehydration can also significantly impact activity levels and influence performance. Quite a lot of people don’t drink enough water, and as a result, have lower energy levels and see reduced mental and physical performance as a result. This is one of the easiest fixes with nutrition, and very often has an outsized impact once fixed.

There are other things that impact the fuelling of activity and performance, but we don’t need this to be an exhaustive list. Ultimately, you want to eat a diet that fuels your activity levels (regardless if that means sitting down all day or exercising for multiple hours per day) and performance (both mental and physical). As a part of this article series, we will be showing you how to set up and adjust the diet to do this.

There is another main goal of nutrition, which is supporting optimal body composition. So let’s discuss that now!

Support Optimal Body Composition

One of the main goals of nutrition is to support optimal body composition. Optimal body composition refers to the optimal ratio of body fat to lean mass (including muscles, bones, and organs) for a given individual and their goals.

This is often thought of purely in terms of some sort of aesthetic ideal, and while this is a reason optimal body composition is important, it is only one of many reasons why optimal body composition is important.

It’s important to keep in mind that optimal body composition doesn’t just refer to body fat, it also refers to lean body mass. Your nutrition practices influence your body fat levels and they also influence your level of muscle mass. Both of these are important variables in most people’s lives in some shape or form.

Optimal body composition is important because it is directly linked to your overall health. Maintaining a healthy body composition is directly linked to reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. Excess body fat, particularly visceral fat around the organs, is a significant risk factor for many health conditions. By optimising your body composition through proper nutrition practices, you can lower your body fat percentage and increase your lean muscle mass, while also improving overall metabolic health.

This is even more important as we age, because maintaining lean muscle mass becomes increasingly important for preserving mobility, independence, and a high quality of life. Optimal body composition can delay the onset of age-related conditions like sarcopenia (muscle loss) and osteoporosis.

Optimal body composition is important for physical performance, both in our daily activities or athletic endeavours. Lean muscle mass contributes to strength, endurance, and functional capacity. It enables individuals to move more efficiently, reducing the risk of injury and enhancing the ability to engage in regular physical activity. Being leaner also generally makes day-to-day life easier, as you are not carrying around excess weight.

Body composition is not just about physical health though, as it also affects mental and emotional well-being. Achieving a healthy balance of body fat and lean mass can improve body image, self-esteem, and overall quality of life. A well-structured nutrition plan that supports body composition goals can help individuals feel more confident in their bodies, reducing the psychological stress associated with body dissatisfaction.

So, optimal body composition is important. It may actually be more important for some individuals and particular goals. Different people have different goals for their physique, and different sports and careers require different body compositions in order to be successful. This makes it hard to give you very specific guidelines as to what an optimal body composition actually is. However, we can provide some very generalised guidelines (which we will explore later in this article series and elsewhere on this site).

To define optimal body composition, we first have to get clear on the terminology.

Optimal Body Composition: Optimal body composition refers to the ideal balance between fat mass and lean mass in the body. Unlike body weight, which is a simple measure of total mass, body composition provides a more nuanced understanding of the body’s make-up, distinguishing between the different types of tissue that contribute to overall health and functionality.

Lean Mass: Lean mass includes muscles, bones, organs, and other non-fat tissues. It’s the metabolically active part of the body, meaning it plays a crucial role in energy expenditure and physical strength. Higher lean mass is associated with greater physical performance, metabolic health, and a reduced risk of chronic diseases.

Fat Mass: Fat mass refers to all the fat tissues in the body, including both essential fat and storage fat. Essential fat is necessary for normal physiological functions, such as hormone production, insulation, and protection of vital organs. However, excess storage fat, particularly visceral fat, can lead to health issues like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

Optimal body composition varies depending on several factors, including age, gender, genetics, and individual goals. But for most people, it means having a lower proportion of body fat and a higher proportion of lean mass. However, what is considered “optimal” can differ quite a bit depending on the population and individual, for example:

- Athletes: Athletes as a general category typically have a higher lean mass and lower body fat percentage to support their specific sports and physical demands.

- Strength and Power Athletes: Strength and power athletes often have high levels of muscle mass, but they can also have high levels of body fat, depending on the specific sport.

- Endurance Athletes: Endurance athletes tend to have lower levels of body fat, and very often, low levels of muscle mass. But this does depend on the exact sport being discussed.

- General Population: For the average person, an optimal body composition balances a healthy level of body fat with enough lean mass to support daily activities, metabolic health, and long-term well-being. In general, most people in the general population have too little muscle and too much body fat.

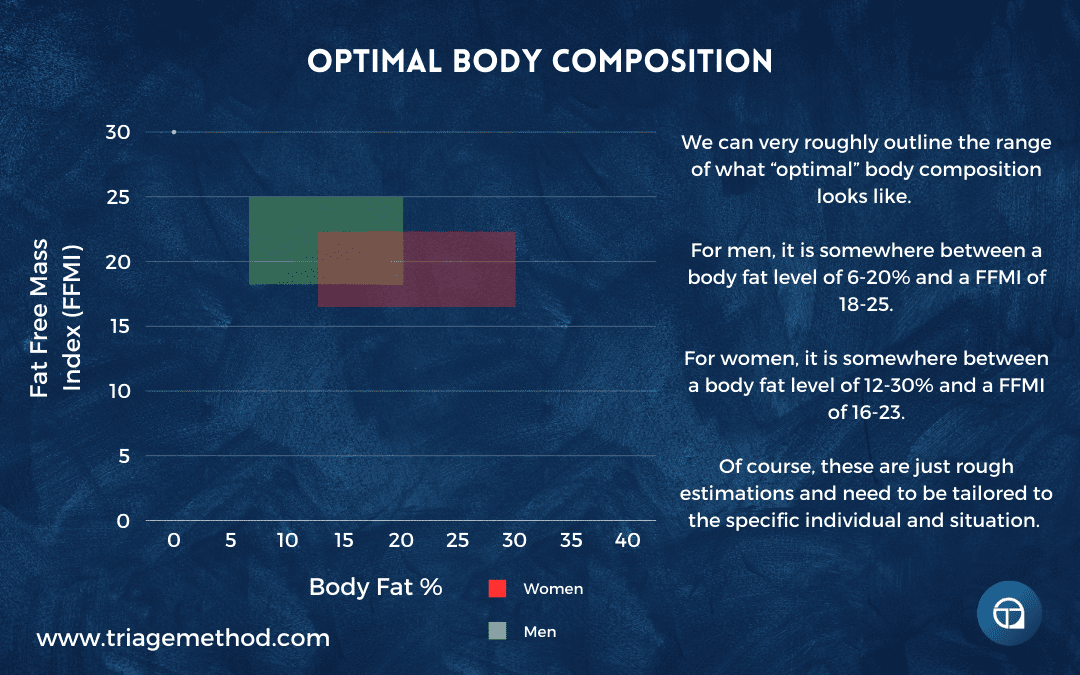

- Sex: Men and women also tend to have differing body composition, and optimal body compositions. Men tend to have more muscle, while women tend to have more body fat.

Now, you may be wondering, “How do I measure my own body composition?” Unfortunately, this is tricky to do, at least in an accurate way. You can really only accurately measure your muscle mass and fat mass during an autopsy. Most of you probably don’t want to know that badly.

However, we do have other methods that can give you a ballpark idea.

The first step is weighing yourself. This should be straightforward enough, as you likely have access to a scale.

Then you need to find out your body fat. This is challenging to do. To measure your body fat, you can use a DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) scanner (unfortunately these can be expensive and most people don’t have easy access), or you can use bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) (this isn’t as accurate as DEXA, but you are more likely to be able to access this, as many gyms have devices for this and so too do many scales), or you can use skinfold measurements (these are the least accurate and depend greatly on the skill of the person taking the measurements).

For most people, getting a scale with built-in bioelectrical impedance capabilities is probably the easiest way to gauge body fat levels.

You can then either use this information to work out your lean mass (this is the percentage of your body that is not fat, so if you are 15% body fat, you are 85% lean mass, and you already know your weight) or you can just read it off from the device (DEXA and BIA scales will often just give you this data).

We can then compare these values to the optimal range. But the only way we can do this is if we take into account height. This is intuitive enough, because if you are 5’5” and have 100kg of muscle and someone else is 6’5” and has 100kg of muscle, they are going to look completely different. While their absolute level of muscle may be the same, their relative level of muscle is very different.

This is generally why many medical establishments like to use body mass index (BMI) to get a quick gauge of where your weight falls in relation to other people. BMI is a simple height-to-weight ratio, but it doesn’t differentiate between fat and lean mass. So it isn’t fit for our purposes here.

We want to compare body fat to muscle mass, while also accounting for height. So for this, we can use fat free mass index (FFMI) as the measure of an individual’s muscle mass relative to their height. It is similar to the Body Mass Index (BMI), but while BMI measures general body mass (including fat), FFMI specifically focuses on fat-free mass, which includes muscle, bone, water, and other non-fat tissues. This makes FFMI a more accurate indicator of muscularity and lean body mass, especially for athletes or individuals with a significant amount of muscle.

The FFMI is calculated using the following formula:

FFMI = Fat-Free Mass (kg)/Height (m)2

Alternatively, it can be expressed as:

FFMI = (Body Weight (kg)×(1−Body Fat Percentage))/Height (m)2

Where:

- Fat-Free Mass (kg) is the total body mass minus the fat mass.

- Height (m) is the individual’s height in meters.

FFMI is a better tool for our purposes because it can be used to compare individuals’ muscularity across different heights and to assess whether someone has an above-average amount of muscle mass for their height.

- Average Male FFMI: Around 18-20.

- Average Female FFMI: Slightly lower than males due to generally lower muscle mass, somewhere around 15-17.

- FFMI > 25: Considered very muscular, often seen in bodybuilders. An FFMI above 25 (or 23 for women) is sometimes considered suspicious for steroid use, although genetic factors can play a role.

You can work out your FFMI with our FFMI calculator.

With this in mind, we can create a rough map of the optimal body composition for men and women.

We will discuss optimal body composition in more depth later on, but for now, this graph hopefully gives you a rough idea of where optimal body composition is.

Consequences of Various Body Composition Scenarios

| Too Much Muscle and Too Little Fat Decreased Hormonal Function: Extremely low body fat, particularly in the presence of high muscle mass, can lead to hormonal imbalances, such as low estrogen in women and low testosterone in men, affecting reproductive health and overall well-being. Impaired Immune Function: Low body fat can compromise the immune system, making the body more vulnerable to infections and illness, even in the presence of high muscle mass. Energy Deficits: Low fat levels mean limited energy reserves, which can lead to fatigue and decreased endurance, particularly during prolonged physical activities. Risk of Nutrient Deficiencies: Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) require dietary fat for absorption. Low body fat levels may lead to deficiencies in these essential nutrients, impacting overall health. Psychological Stress: Maintaining a very low body fat percentage, especially with high muscle mass, can be difficult and stressful, potentially leading to issues like body dysmorphia, disordered eating, or overtraining. | Too Much Muscle and Too Much Fat Excess Strain on the Cardiovascular System: Carrying excessive amounts of both muscle and fat can place a significant strain on the heart and blood vessels, increasing the risk of hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Joint and Mobility Issues: The added weight from both muscle and fat can put extra pressure on joints, leading to wear and tear, pain, and conditions like osteoarthritis. Metabolic Imbalance: While muscle mass generally supports metabolic health, excessive fat can offset these benefits, potentially leading to insulin resistance and other metabolic disorders. Respiratory Problems: Excess body mass, particularly when it includes high levels of fat, can contribute to breathing difficulties, sleep apnea, and decreased lung function. Increased Risk of Injury: A combination of high muscle mass and fat may lead to an imbalance in movement patterns, increasing the likelihood of strains, sprains, and other injuries. |

| Too Little Muscle and Too Little Fat Decreased Strength and Functionality: Insufficient muscle mass leads to reduced physical strength, making daily activities more challenging and increasing the risk of injuries. Compromised Metabolic Health: Low muscle mass can result in a slower metabolism, making it harder to maintain energy levels and manage weight. Hormonal Imbalances: Extremely low body fat can disrupt hormone production, particularly sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone, leading to menstrual irregularities in women and reduced libido and fertility in both genders. Weakened Immune System: Both low muscle and fat reserves can weaken the immune system, making the body more susceptible to infections and illnesses. Poor Bone Health: Low muscle mass can contribute to decreased bone density, increasing the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. | Too Little Muscle and Too Much Fat Increased Risk of Chronic Diseases: Excess fat, particularly visceral fat, combined with low muscle mass, significantly raises the risk of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions. Decreased Mobility and Functional Capacity: Low muscle mass can impair mobility and physical function, while excess fat can exacerbate these issues, leading to difficulties in performing everyday tasks. Reduced Metabolic Rate: Low muscle mass lowers the basal metabolic rate (BMR), making it easier to gain weight and harder to lose fat. Higher Inflammation Levels: Excess body fat, especially around the abdomen, is associated with increased inflammation, which can contribute to various health problems, including joint pain and autoimmune conditions. Poor Mental Health: The combination of low muscle mass and high body fat can negatively impact self-esteem and body image, potentially leading to anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. |

Getting to and maintaining an optimal body composition is one of the main goals of nutrition. The way you set up your diet profoundly impacts your ability to both lose fat (and keep it off) and build muscle (and keep it). We will be discussing the intricacies of this throughout this article series, so I won’t dig into how the diet does this here. Needless to say, your nutrition is important for supporting optimal body composition, and this is one of the main goals of nutrition.

The Additional Goals of Nutrition

While the main goals of nutrition are to support health, fuel activity and performance, and support optimal body composition, there are also other goals of nutrition.

We have evolved to enjoy nutrition. While we don’t often think of it, we enjoy food for several reasons that are deeply rooted in evolutionary biology. These reasons generally revolve around the basic need for survival, the drive for optimal nutrition, and the development of social structures.

At the most fundamental level, humans enjoy food because it is essential for survival. From an evolutionary perspective, the primary purpose of eating is to obtain energy and nutrients needed for survival, growth, and reproduction.

Evolution has wired humans to find eating pleasurable because it reinforces the behaviour necessary to sustain life. Foods rich in calories, such as fats and sugars, are particularly enjoyable because they provide a quick (and often plentiful) source of energy, which would have been crucial for early humans who faced periods of food scarcity. Humans that didn’t evolve to really enjoy food likely wouldn’t have survived and reproduced as successfully as those that did.

The human sense of taste evolved to detect essential nutrients, which aids us in achieving optimal nutrition. Sweetness often indicates energy-rich carbohydrates, bitterness can signal potentially harmful toxins, and umami reflects protein content. By enjoying these flavours, humans are naturally guided toward consuming a relatively balanced diet that supports health and fitness. At least in the context of the world we evolved in. However, these taste desires are often at odds with the current food environment where you can very easily access an excess of calories and flavours, while eating a very unbalanced diet.

Humans develop preferences based on past experiences with food, and this can add to the enjoyment of food (or detract from it). Positive experiences, such as eating a favourite meal, trigger the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward. This creates a positive reinforcement loop, making humans more likely to seek out and enjoy similar foods in the future.

Enjoyment of food also helps humans learn what is safe and nutritious to eat. Early humans who enjoyed foods that were nutritious and safe to eat were more likely to survive, while those who disliked or avoided such foods may have faced nutritional deficiencies. So we have evolved to enjoy certain tastes and flavours.

So we have evolved to enjoy food, and this is one of the additional goals of nutrition. This enjoyment of food is fairly intuitive, but we are unfortunately now at a mismatch between the current environment and the evolved environment. We still enjoy the flavours that are likely to lead us to gain excess fat in the current environment.

Related to this, we also evolved to use food as a source of comfort, stress relief and reward. Food can provide comfort and reduce stress, and most of you have likely experienced this. During times of stress or scarcity, eating can stimulate the release of endorphins and other neurotransmitters that improve mood, providing a psychological buffer against the challenges of survival. Many humans still use food as a source of comfort or stress relief in modern times.

“Comfort food” is something that almost everyone can relate to, whether it’s indulging in a favourite dish after a tough day or snacking on something sweet when feeling anxious. In today’s world, people often experience stress from various aspects of life. Unfortunately, in many cases, food is used as a coping mechanism, not necessarily because people are hungry, but because it provides temporary relief from stress. This is rooted in our evolutionary biology: food releases feel-good chemicals like endorphins, providing short-term emotional comfort.

However, this can lead to unintended consequences in modern environments. With the easy availability of calorie-dense, highly processed foods, many individuals overeat in response to stress, leading to weight gain and associated health problems. The foods that are most comforting (rich in fats, sugars, and salt) are often the ones that drive people to consume more calories than they actually need. This creates a cycle where food temporarily alleviates stress but contributes to long-term health challenges, such as obesity and metabolic disorders. So while food still serves the purpose of comfort and stress relief, it may not always serve our health goals in the way it once did.

Food is also often used as a reward. When you eat something pleasurable, like a favourite snack or meal, your brain releases dopamine (a neurotransmitter involved in the sensation of pleasure and reward). This dopamine response encourages repeated behaviours, reinforcing the act of eating. In evolutionary terms, this reward system developed to help humans seek out food, ensuring survival. Early humans needed strong motivators to hunt, forage, and eat because these activities required significant effort.

In the modern food environment, however, this reward system can be easily hijacked. The food industry has become adept at creating hyper-palatable foods that stimulate the brain’s reward centres far more than natural foods would. These processed foods are engineered to be addictive, leading to overconsumption. Many people today use food as a reward when other areas of their life may lack fulfilment or aren’t going how they want them to go (whether it’s work, personal relationships, or a feeling of a lack of achievement in life’s goals). Instead of food being a reward for survival-based activities, it often becomes a substitute reward for emotional or psychological satisfaction. This shift has profound implications for health, as using food as a primary reward can contribute to overeating and chronic health issues like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Another important aspect of nutrition is its role in social bonding and cultural expression. Sharing food has long been a fundamental social activity. For early humans, eating together promoted cooperation, strengthened bonds within the group, and enhanced survival. Sharing resources meant greater protection and support, and it helped create trust and solidarity within a community. Even today, people come together over food, whether it’s a family dinner, a festive celebration, or a casual gathering with friends. The simple act of eating together strengthens social ties, reinforces group identity, and fosters a sense of belonging.

Culturally, food is much more than just sustenance. Different societies have evolved distinct cuisines, meal rituals, and food-related traditions that are deeply ingrained in cultural identity. The pleasure people derive from food often extends beyond taste and it’s tied to the social and cultural contexts in which food is consumed. In many cultures, certain foods are associated with rituals, holidays, or rites of passage, and these traditions provide comfort, continuity, and a sense of shared experience.

However, while food certainly supports social relationships, this is a much smaller goal of nutrition than most people make it out to be. People often act as if everything they eat is part of a communal or social experience, and eating any other way is impossible. But the reality is quite different.

For most people, communal meals are rare. Many people eat alone or in individualistic ways, such as grabbing a quick lunch at their desk or eating breakfast on the go. Even within families, shared meals may happen only once a day, if that. The majority of food consumption happens in isolation in the modern world (either individually eating food, or eating food that is individually chosen/prepared), which means that while eating together can promote social bonds, it’s not the primary focus of nutrition.

Overall, while food can serve multiple purposes (e.g. providing enjoyment, comfort, acting as a reward, and fostering social bonds) the primary goals of nutrition remain: supporting health, fueling activity and perfromance, and promoting optimal body composition. Understanding how these additional factors influence our eating habits is crucial, especially in today’s food environment, where our evolved desires for certain tastes and food-related behaviours can sometimes work against our health, performance and body composition goals.

Finding Your Balance

When it comes to nutrition, finding a balance that works for you is key. Everyone’s nutritional needs and preferences are unique, and while we have discussed the main general goals that apply to most people (supporting health, fueling activity and performance, and achieving optimal body composition), how you prioritise these goals will depend on your individual circumstances, preferences, and lifestyle. It’s important to recognise that nutrition isn’t one-size-fits-all, and finding your personal balance means weighing these goals based on what’s most important to you.

Having coached a lot of people, I have been fortunate to play a role in helping a lot of people to understand their own goals and priorities. And let me tell you, this is a really important part of creating a nutrition plan that actually makes sense for you and is something you can see yourself sticking to for a longer period of time. However, it can be a little bit difficult to do, as we often don’t really know how we actually want to prioritise things, as we don’t know what the trade offs are. So I just want to finish this discussion of the goals of nutrition off with a brief discussion of how to find your own priorities and a few common ways that people prioritise their goals (so you can see the trade offs and what that would roughly look like in practice).

What Are Your Specific Goals with Nutrition?

To determine what your balance looks like, you do just need to sit down and start trying to identify your specific goals with nutrition. Are you primarily focused on improving your health and preventing disease? Is your main priority fueling athletic performance or enhancing physical fitness? Perhaps you are most concerned with body composition, aiming to lose fat or gain muscle. Or maybe you value the enjoyment of food above all else and see nutrition as a way to enhance your overall life experience.

There’s no right or wrong answer here, as it’s about understanding your personal priorities and making food choices that align with them. However, you may also find that these goals can sometimes be in conflict, and this is where the real balancing act comes in. For example, you might have a goal of improving your health but also love indulging in your favourite comfort foods. Striking a balance between these goals allows you to enjoy food without compromising your long-term health. Balancing conflicting goals is one of the main reasons people come to us for coaching, as the cookie-cutter information you find on online won’t allow you to resolve the conflict between your goals, and tailor a plan specifically for your needs.

Balancing The General Goals with Your Personal Priorities

Here are some examples of how you might balance the general goals of nutrition with your own personal priorities:

- Prioritising Health Above All Else: If your primary goal is to support long-term health, you might focus on choosing nutrient-dense foods that provide essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. You would likely aim for a diet rich in whole foods (like fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, whole grains, and healthy fats) while limiting processed foods high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats. While this approach can sometimes mean sacrificing immediate enjoyment (such as passing on that dessert or choosing a healthier option at a restaurant), the long-term benefits to your health may outweigh those short-term pleasures. For example, if you’re managing a chronic condition like diabetes or heart disease, you might find that the goal of optimal health becomes more urgent, and the enjoyment of certain foods takes a backseat.

- Fueling Athletic Performance as a Top Priority: If your main goal is athletic performance, your nutritional balance might look quite different. In this case, you’d likely focus on eating for energy and recovery. You might need to consume higher amounts of carbohydrates to fuel workouts, ensure you’re getting enough protein for muscle repair, and pay close attention to hydration and nutrient timing. While you might still enjoy the taste of the food you eat, performance-oriented nutrition often requires a more structured approach. For example, athletes might prioritise meals that maximise performance outcomes even if they aren’t the most flavourful. In this case, enjoyment of food may take second place to the goal of optimising physical performance.

- Balancing Health with Enjoyment: Perhaps you value both health and enjoyment equally and want to strike a balance between the two. In this case, you might follow a “moderation” approach, where you make mostly healthy choices but allow yourself to indulge in your favourite foods in a controlled manner. For example, you might eat nutrient-rich meals throughout the week but enjoy a few indulgent treats over the weekend. This way, you’re still supporting your health goals but not depriving yourself of the pleasures that food can offer. This type of balance can be sustainable for many people, as it provides flexibility without sacrificing overall well-being.

- Placing Enjoyment Above Optimal Health: On the other hand, perhaps you place a higher value on the enjoyment of food than on strict adherence to health or fitness goals. For some people, food is a central part of their life’s enjoyment, whether that means exploring new cuisines, indulging in rich, flavorful meals, or simply enjoying social gatherings that revolve around food. If this is your priority, you might be more willing to accept certain trade-offs when it comes to health or body composition. For instance, you may not be overly concerned with counting calories or macronutrients, instead focusing on eating foods that bring you the most joy. While this approach may not align with strict health guidelines, it’s a valid choice for those who prioritise the enjoyment of food as an integral part of their overall happiness, as long as they accept the trade-offs.

- Focusing on Weight Management or Body Composition: If your goal is to change your body composition (whether that’s losing fat or gaining muscle) your nutritional choices will likely need to be more precise and controlled. You might focus on tracking your caloric intake, hitting specific macronutrient targets (such as eating a high-protein diet for muscle growth), and timing your meals to support your body composition goals. While you may still enjoy your food, the focus tends to be on achieving physical changes, and you might limit indulgences that don’t align with those goals. For example, someone aiming to lose fat might pass on dessert or opt for lower-calorie options, knowing that it supports their ultimate goal of fat loss. Conversely, someone focused on gaining muscle might prioritise high-calorie, nutrient-dense foods even if they’re not always the most enjoyable.

There are of course many other potential combinations and different goal combinations. But these are just a few that we commonly see in our coaching practice. Hopefully, they give you a rough idea of how things may need to be tweaked depending on specific goals/goal combinations.

Ultimately, the key to finding your balance is recognising that your nutritional goals are personal and can evolve over time. There may be periods when you focus more on health, times when performance takes centre stage, or moments when the enjoyment of food becomes your main priority. The important thing is to be mindful of how your current goals align with your overall lifestyle and to make adjustments when and where necessary.

It’s also important to remember that nutrition isn’t about perfection. Whether you’re focusing on health, performance, body composition, or enjoyment, it’s about finding a balance that works for you, supports your well-being, and makes you feel good in the long run.

Unfortunately, some goals are somewhat antagonistic to each other and this can make things very difficult. To solve this, you need to be very clear on your priorities and to understand how to adjust the diet to accomplish your goals. a periodised approach may also be needed. We will go through a lot of nutritional principles in this article series that will allow you to really tailor your nutrition to your goals.

The Goals of Nutrition Conclusion

Hopefully, this article has given you a good idea of the goals of nutrition. There are many goals of nutrition, but when you boil it down, the main goals are to support health, fuel activity and performance, and support optimal body composition. There are peripheral goals to this too, such as enjoyment. You have to find the balance between the different goals that is right for you. You may have different priorities and life situations, and as such, your goals of nutrition may be weighted differently.

Ultimately, you are going to need to optimise your diet and tailor it to your specific goals. You can do this by reaching out to us and getting online coaching, or alternatively, by interacting with our free content. This article series will show you the basics of how to dial in your nutrition, but if you have specific goals, you will generally need a more specific approach to the diet.

If you want more free information on nutrition, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

The previous article in this series is about Why Nutrition Is Important and the next article in this series is Types Of Diets, if you are interested in continuing to learn about nutrition. You can also go to our nutrition hub to find more nutrition content.

References and Further Reading

Padwal R, Leslie WD, Lix LM, Majumdar SR. Relationship Among Body Fat Percentage, Body Mass Index, and All-Cause Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(8):532-541. doi:10.7326/M15-1181 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26954388/

Holmes CJ, Racette SB. The Utility of Body Composition Assessment in Nutrition and Clinical Practice: An Overview of Current Methodology. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2493. Published 2021 Jul 22. doi:10.3390/nu13082493 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8399582/

Campa F, Toselli S, Mazzilli M, Gobbo LA, Coratella G. Assessment of Body Composition in Athletes: A Narrative Review of Available Methods with Special Reference to Quantitative and Qualitative Bioimpedance Analysis. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1620. Published 2021 May 12. doi:10.3390/nu13051620 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8150618/

Kuriyan R. Body composition techniques. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(5):648-658. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1777_18 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30666990/

Lemos T, Gallagher D. Current body composition measurement techniques. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24(5):310-314. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000360 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28696961/

Duren DL, Sherwood RJ, Czerwinski SA, et al. Body composition methods: comparisons and interpretation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(6):1139-1146. doi:10.1177/193229680800200623 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2769821/

Wells JC, Fewtrell MS. Measuring body composition. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(7):612-617. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.085522 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2082845/

Kudsk KA, Munoz-Del-Rio A, Busch RA, Kight CE, Schoeller DA. Stratification of Fat-Free Mass Index Percentiles for Body Composition Based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Bioelectric Impedance Data. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017;41(2):249-257. doi:10.1177/0148607115592672 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26092851/

Merchant RA, Seetharaman S, Au L, et al. Relationship of Fat Mass Index and Fat Free Mass Index With Body Mass Index and Association With Function, Cognition and Sarcopenia in Pre-Frail Older Adults. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:765415. Published 2021 Dec 24. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.765415 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35002957/

Hull HR, Thornton J, Wang J, et al. Fat-free mass index: changes and race/ethnic differences in adulthood. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(1):121-127. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.111 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3306818/

Currier BS, Harty PS, Zabriskie HA, et al. Fat-Free Mass Index in a Diverse Sample of Male Collegiate Athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(6):1474-1479. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003158 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30985525/

Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE, Blue MNM, et al. Fat-Free Mass Index in NCAA Division I and II Collegiate American Football Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(10):2719-2727. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001737 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5438288/