Are you aware of the cognitive distortions holding your nutrition back? Most people aren’t.

When most people talk about their nutrition struggles, they blame themselves.

“I just don’t have enough willpower.”

“I need to be more disciplined.”

“I’m too weak to stick to anything.”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard some version of that. But after years of coaching clients through their nutrition, fitness, and lifestyle habits, I’ve learned that it’s rarely discipline that’s failing. More often, it’s their thoughts holding them back.

The kind that slips in when you’re tired, stressed, or just trying to do your best. The kind that tells you, “You already messed up today, might as well keep going.” Or “You’ve never been able to stick to anything, why would this be different?” Or that sneaky one that whispers, “If it’s not perfect, it’s pointless.”

Those thoughts feel real in the moment. They feel like facts. But they’re not. They’re distortions; mental habits your brain has practised so many times that they’ve started to feel like the truth. And they shape the way you experience food, your body, and your health long before you make a single decision about what to eat or whether to train.

I’ve worked with hundreds of people, from busy parents to high-performing professionals, from lifelong dieters to complete beginners, and over time, I noticed a pattern: the biggest breakthroughs didn’t happen when someone found the perfect macro split, the ideal workout split, or the trendiest supplement.

They happened when they changed the way they thought about their choices.

When someone stopped labelling foods as “good” or “bad,” everything got easier. When they realised that one unplanned meal wasn’t a catastrophe, their confidence grew. When they stopped tying their entire self-worth to a number on a scale, real progress became possible.

This is why your thoughts matter more than you think. They’re the lens through which you experience every part of your health journey. If that lens is warped, every choice can start to feel like a referendum on your character. But when the lens is clear, a choice is just a choice. No drama, no spiral.

It’s important to keep in mind that these distorted thought patterns are learned. They’re shaped by years of cultural messaging, past experiences with dieting, perfectionism, and the brain’s natural tendency to fixate on threats. They tend to show up in the very moments when we’re vulnerable, like when we’re exhausted, stressed, or chasing perfection. That’s when the inner critic pipes up, convincing us that a single imperfect decision means we’ve failed altogether.

But they’re not permanent. Mental habits can be retrained just like physical ones.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus is widely attributed as once saying, “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.” Nutrition is one of the most vivid, everyday examples of this truth. A missed workout, a late-night snack, or a weekend of takeaway food, none of these things ultimately decides your health trajectory.

What matters is how you respond in the moments after. Do you spiral into self-blame, or do you take a breath, adjust, and keep moving forward?

When you start to shift how you think, the entire process of taking care of yourself changes. Food stops feeling like a moral test. Movement stops being punishment. Health stops being all-or-nothing. That’s when progress actually begins. So, let’s actually tackle the cognitive distortions holding your nutrition back and discuss exactly what to do about them!

TL;DR

Most people think their nutrition struggles come down to a lack of willpower. But often, it’s not discipline that fails, it’s distorted thinking that pulls you off track. All-or-nothing beliefs (“I blew it”), moralising food (“good” vs. “bad”), or catastrophising a single slip can shape how we eat, move, and feel long before we make a single decision. These thought patterns are learned, automatic, and convincing, but they are not facts.

When you catch these distortions, name them, and choose how to respond, you can begin to shift your nutrition habits for good. Approaches like cognitive restructuring, acceptance and defusion, self-compassion, and smart environmental design help turn a spiral into a simple course correction. Over time, this builds consistency without shame or perfectionism.

This isn’t about controlling every thought. It’s about seeing thoughts for what they are, stories, not commands, and then acting in alignment with your values. When the lens clears, food stops being a moral test and becomes part of a balanced life.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 What Are Cognitive Distortions (And Why They Matter in Nutrition)?

- 3 Why These Distortions Show Up

- 4 Common Cognitive Distortions in Nutrition (And How to Handle Them)

- 5 Recognising Your Own Patterns (Before You React)

- 6 Big Skills That Actually Work

- 7 Putting It All Together

- 8 What Happens If We Don’t Do This Work

- 9 The Cognitive Distortions Holding Your Nutrition Back: Conclusion

- 10 Author

What Are Cognitive Distortions (And Why They Matter in Nutrition)?

If you’ve ever found yourself spiralling after one unplanned meal or convincing yourself you’ve “blown it” because you missed a workout, you’ve experienced what’s known as a cognitive distortion.

A cognitive distortion is a habitual, automatic way of thinking that feels true in the moment but doesn’t actually reflect reality. It’s not you being dramatic or weak; it’s just the brain running an old script it knows off by heart. These scripts are fast, convincing, and emotionally charged. However, if you don’t notice them, they can shape how you experience your entire health journey.

I see this all the time with clients. Someone has a small detour, maybe they grab a biscuit with their tea in the office break room, or sleep through an early workout, and the brain jumps straight to extremes: “I always screw this up” or “I might as well start over Monday.”

One choice turns into a story, and that story influences the next choice, and the next one, until what began as a single moment becomes a whole pattern.

This is why cognitive distortions matter so much in nutrition. They’re not just mental noise in the background, they can directly sabotage behaviour change. They chip away at confidence, feeding an all-or-nothing mindset that keeps people stuck in the same loops. The really cruel part is that most of this happens under the surface. By the time you’re aware of it, the damage often feels “done,” even though it isn’t.

The key insight here is that your thoughts are not facts. They’re interpretations. They’re stories your brain tells to make sense of what’s happening, often shaped by past experiences, cultural messages, and old habits. Just because a thought shows up doesn’t mean it’s accurate, or even useful.

I like how William James put it through his lens of pragmatism. An idea is only “true” if it helps us live better. If a thought leaves you discouraged, ashamed, or stuck, then it might not be the truth, just a distortion wearing a very convincing mask.

In my coaching, it is often the case that before someone can build new habits, they have to build a new narrative. This ties directly to the concept of self-efficacy and the belief in your ability to influence outcomes. Real change doesn’t begin with the perfect plan. It begins with learning to recognise and question the thoughts that shape your actions in the first place.

Once you stop taking every thought as gospel, you stop being pushed around by your old mental scripts. From there, real behaviour change gets a whole lot easier.

Why These Distortions Show Up

If cognitive distortions are so unhelpful, why do they show up so easily and so often? This is a question I hear from clients all the time, usually asked with a mix of frustration and guilt. The answer isn’t that there’s something “wrong” with you. It’s that your brain is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

Cognitive distortions don’t appear out of nowhere; they have deep biological, psychological, and cultural roots. Once you understand where they come from, it’s easier to meet them with awareness instead of self-blame.

Let’s start with the most basic layer: biology.

Your brain evolved to prioritise survival, not self-compassion. From an evolutionary perspective, paying more attention to what might hurt you than to what’s going well was an advantage. This is called negativity bias. It’s why one “bad” food choice can feel so much bigger than a dozen good ones. The brain latches on to mistakes and plays them on repeat because your nervous system was built to detect threats, not have you flourishing.

Then there’s something called reward prediction error. When reality doesn’t match your expectations (maybe you planned a “perfect” day of eating and ended up grabbing fast food), your brain reacts strongly. The gap between “what I thought would happen” and “what actually happened” creates a disproportionate emotional response. It’s why a small, neutral event can suddenly feel like a failure.

And of course, there’s habit. Cognitive distortions often travel down the same well-worn neural pathways as your old behaviours. If for years you’ve responded to slip-ups with self-criticism, those reactions become automatic. Like a well-trod trail through the woods, your brain goes down the familiar path even when it’s not helpful.

But biology isn’t the whole story, and psychology plays a huge role too.

Many distortions are fueled by perfectionism and the relentless belief that anything less than flawless means failure. Add fear of failure or painful past dieting experiences, and you’ve got fertile ground for black-and-white thinking.

This is also where mindset comes in. Carol Dweck famously distinguished between a fixed mindset (where abilities and outcomes are seen as fixed) and a growth mindset (where they’re seen as trainable). In a fixed mindset, a single slip-up isn’t just a mistake; it’s proof of who you are. Distortions thrive in that kind of environment.

And then, of course, there’s the world around us. We live in a culture steeped in moralising food: “good” vs. “bad,” “clean” vs. “junk”. Diet culture makes perfection seem normal and failure seem personal. Add in the constant feed of curated bodies and meals on social media, and social comparison becomes a daily reflex. It’s no wonder distorted self-assessments flourish in that environment.

The Stoic philosopher and Emperor of Rome, Marcus Aurelius, taught us that humans act according to their nature. But we can actually train our nature. Distorted thinking may be natural, but it isn’t permanent. Mental habits, like physical ones, can be retrained through awareness and practice. We have the capacity to shape our character through deliberate thought and practice. Stoic philosophy teaches that while impressions and impulses may arise naturally, we can choose how to respond to them, and through repeated practice, we can strengthen reason over unhelpful reactions.

Ultimately, awareness is always the first step here. You can’t change a distortion you don’t see. But once you start recognising where these thought patterns come from, and why they feel so convincing, you take their power away. You stop treating them like hard truths and start treating them like what they are: learned habits that can be unlearned.

Common Cognitive Distortions in Nutrition (And How to Handle Them)

The thing about cognitive distortions is they’re sneaky. They don’t usually announce themselves with flashing lights. They slip in disguised as simple, and oftentimes, seemingly reasonable truths. They sound like your own voice, which is why they’re so convincing.

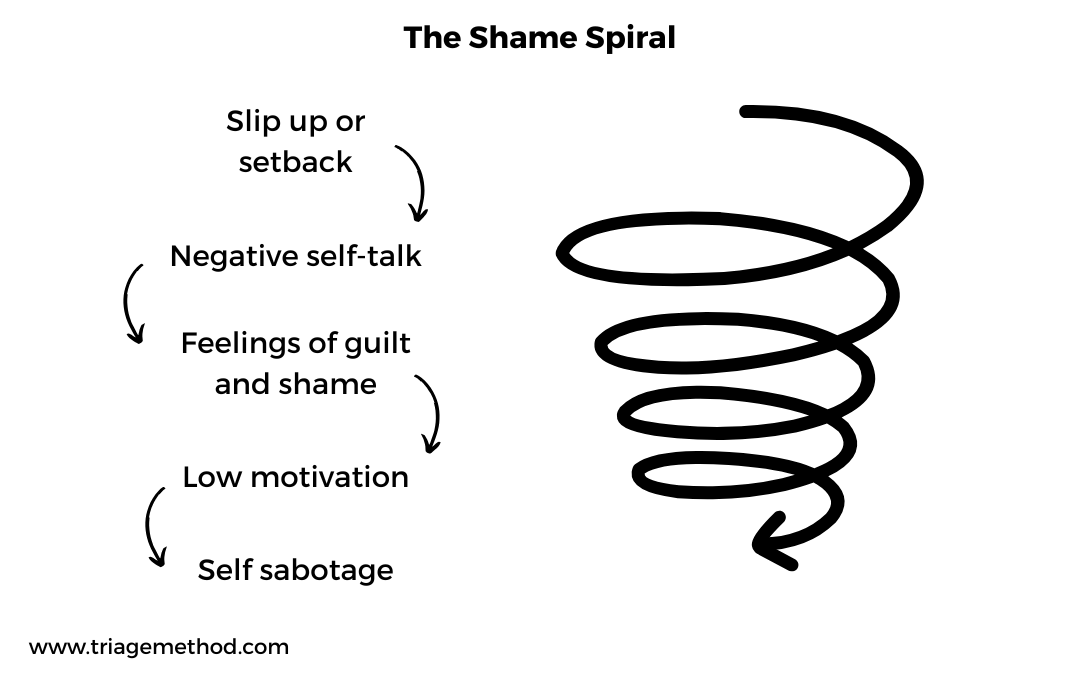

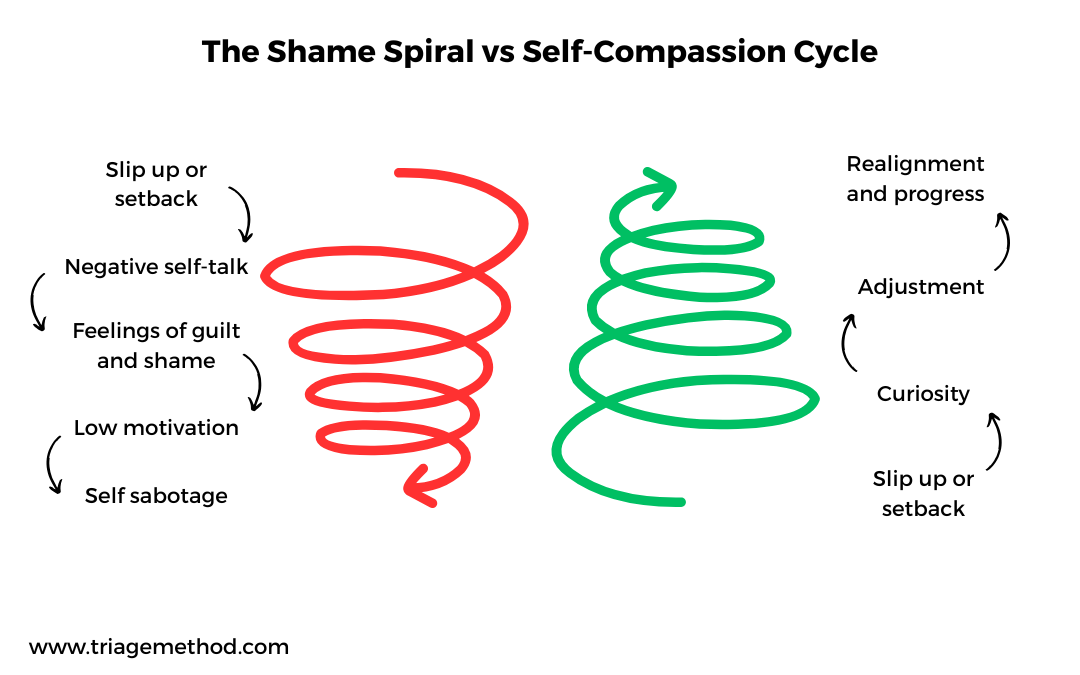

In nutrition, these distortions often shape the way people interpret their actions, talk to themselves, relate to others, and imagine their future. A single thought like “I’ve already messed up today” can snowball into a whole chain of behaviours such as skipping meals, overeating, giving up for the week, feeling ashamed, starting over, and repeating the cycle.

But once you can name these distortions, you can start to separate “you” from the story your brain is telling. You can pause, zoom out, and make a different choice.

In this section, we’ll look at some of the most common cognitive distortions that show up in nutrition. These are the ones I see over and over again in my clients. For each one, I’ll walk you through how it shows up, why it happens, and practical strategies to handle it.

Because this isn’t about “fixing” yourself. It’s about understanding your mental patterns so you can work with your mind instead of being dragged around by it.

Once you can name the distortion, you can catch it. And once you can catch it, you can change the way it shapes your choices.

A. How You Interpret Your Actions

One of the most common ways cognitive distortions show up in nutrition is in how people interpret their own actions.

This is the inner commentary that runs after a choice is made. It’s what you tell yourself about what just happened. It can turn neutral moments into emotional landmines and small detours into big spirals.

For many of my clients, this isn’t loud, dramatic self-talk. It’s subtle. A single thought like “I shouldn’t have eaten that” can shift the tone of an entire day. A small decision starts carrying way more weight than it deserves.

Let’s break down some of the most common patterns I see, and how to handle them in a practical, real-world way.

All-or-Nothing Thinking

This is the classic “I messed up once, so the day’s ruined” trap.

You planned to eat a balanced breakfast, got off track at lunch, and suddenly you’re telling yourself there’s no point trying for the rest of the day. This kind of black-and-white logic makes every small deviation feel like total failure.

But your health isn’t determined by a single meal, it’s shaped by patterns over time. In cognitive-behavioural terms, the best tool to use here is cognitive restructuring: catching the extreme thought and challenging it with a more balanced perspective.

When dealing with all-or-nothing thinking, I try to keep in mind what the philosopher Aristotle described virtue as. He said it was lying between extremes, and what he described as the “golden mean.” In nutrition, that might mean recognising that a burger isn’t a moral crime and a salad isn’t a badge of virtue.

They’re just food choices.

One meal doesn’t define your health. One raindrop doesn’t make a storm.

Moralising Food (Black-and-White Rules)

“I was good today.” “I was bad today.”

If you’ve ever said something like that, you’ve experienced how culture sneaks moral judgment into eating. From an early age, many of us learn to categorise foods as “good” or “bad.” But when you make food moral, every choice starts to feel like a test of character, and that’s a heavy way to live.

Diet culture and food marketing teach us to load food with moral meaning. But existentialism reminds us that meaning isn’t inherent; we create it.

A cookie isn’t good or bad until we decide it is. A salad isn’t a moral triumph. It’s just food.

You’re the one who chooses what it means.

Overgeneralisation

This one sounds like: “I always fail at this.”

A single setback gets turned into a sweeping statement about your entire identity. One skipped workout becomes “I can’t stick to anything.”

In coaching, this is a crucial moment to build self-efficacy, which is the belief that you can influence your outcomes. One way to do that is to identify exceptions, such as the times you didn’t “always” fail. Those moments break the illusion of the absolute.

A useful tool here comes from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: defusion. Instead of fusing with the thought (“I always fail”), you create space from it: “I’m noticing the thought that I always fail.” It’s a subtle shift, but it breaks the spell.

Mental Filter

Imagine your day has 10 neutral or positive moments and one less-than-ideal choice. If your brain only focuses on that single misstep, you’re in the mental filter trap.

This happens because of your brain’s built-in threat detection system is wired to amplify negatives to keep you safe. But when it comes to nutrition, this just reinforces shame and discouragement.

A simple way to counter this is to consciously highlight the neutral and positive. I often have clients end the day by naming three things they did well, not perfect, just well or even neutral. It balances the lens back toward reality instead of distortion.

Discounting the Positive / Magnification-Minimisation

This distortion whispers, “Yeah, but it wasn’t enough to matter.”

Maybe you prepped a healthy lunch, but your brain focuses on the dessert after dinner. Or you went on a walk, but because it wasn’t a “real workout,” you dismiss it.

This is where Stoic realism steps in to strip away the story and see what’s actually there. A walk is a walk. A good meal is a good meal. Neither is meaningless just because it wasn’t “perfect”. As Marcus Aurelius reminds us, “You have power over your mind, not outside events. Realise this, and you will find strength.”

Small actions are real actions. They count. They add up

In coaching, I remind clients that wins compound. One good choice might not feel like much in isolation, but layered over time, it builds habits, confidence, and momentum. Dismissing those small wins is like emptying your own gas tank halfway through the trip.

These distortions aren’t the only ones you’ll face, but learning to master how you interpret your actions gives you a crucial kind of freedom. When you stop letting your mind exaggerate failures or erase small wins, you reclaim control over what’s actually yours: your choices, your perspective, and your effort. That’s where real mastery over your nutrition begins to take shape.

B. How You Talk to Yourself

The way you talk to yourself shapes your entire experience of change.

You can have the most thoughtful nutrition plan, the smartest workout program, and a perfectly set-up environment, but if the voice in your head is harsh, rigid, or unforgiving, every actions feels heavier than it needs to be.

This is why I pay close attention to the language my clients use with themselves. Often, the real roadblock isn’t lack of information or strategy, it’s the phrases they repeat in their heads without realising how much power those words hold.

Let’s break down a few of the most common distortions that show up in self-talk and how to work with them.

“Should” Statements

This one sneaks in everywhere: “I should be better by now.” “I should have more discipline.” “I should know better.”

“Should” is a loaded word. It sounds like accountability, but in practice, it often creates guilt and pressure instead of growth. It focuses on what you’re not, rather than what’s possible. It also denies your own agency.

Jean-Paul Sartre believed we are always choosing, whether we like it or not. Even saying “I should” is a kind of choice, but it sounds like we’re being judged from the outside. It turns an active decision into a passive obligation. When something feels like an obligation, motivation and self-trust shrink.

A powerful CBT strategy here is to reframe “should” into “could.”

- “I should work out” → “I could work out.”

- “I should eat better” → “I could make a different choice next time.”

Replacing “I should” with “I choose” or “I want” or “I get to” is powerful because it puts the agency back where it belongs, in your hands. That shift might seem small, but it can change how you relate to food, movement, and your goals.

Labelling

“I’m lazy.” “I’m weak.” “I’m undisciplined.”

This distortion takes a single action, such as skipping a workout, eating something impulsively, or not following through, and turns it into a permanent identity. Instead of saying, “I didn’t do what I planned,” the mind declares, “I am the kind of person who can’t do this.”

But behaviour is not identity.

One of the most important mindset shifts is separating who you are from what you do. Missing a workout doesn’t make you lazy any more than eating dessert makes you bad. It just means you made a choice. One of thousands over a lifetime.

Virtue ethics, going all the way back to Aristotle, reminds us that character isn’t forged in a single decision, it’s shaped through repeated actions over time. For Aristotle, virtues weren’t lofty ideals to admire from a distance. They were habits to be cultivated through practice. You become patient by practising patience, courageous by doing courageous things, disciplined by showing up repeatedly.

As Will Durant famously paraphrased Aristotle, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

One choice doesn’t define you. What matters is the pattern, the trajectory, the overall shape of your behaviour. A single detour doesn’t change the destination if you keep moving in the right direction. When you zoom out and look at the arc of your actions, not just the bumps along the way, you see where your character is truly being formed.

So the next time that label pops up, challenge it.

- “I’m lazy” → “I didn’t follow through today.”

- “I’m weak” → “I made a choice I want to learn from.”

Ultimately, a label is just a shortcut your brain uses, and it’s not the truth. Your identity is shaped by what you keep doing, not by one moment.

Emotional Reasoning

This one is subtle but still quite powerful: “I feel hopeless, so it must be hopeless.”

When emotions run high (frustration, guilt, shame, overwhelm) the brain can confuse feelings with facts. But feelings are not evidence. They’re signals, like weather patterns passing through. Just because you feel stuck doesn’t mean you are stuck.

A useful tool from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is defusion. Normally, when strong thoughts or emotions arise, we tend to fuse with them — treating them as literal truths rather than passing experiences. “I’m hopeless” stops feeling like a thought and starts feeling like a fact about who we are.

Defusion creates a little breathing room. Instead of being inside the thought, you step next to it:

“I’m noticing I’m feeling hopeless right now.”

“I’m having the thought that I can’t do this.”

“I’m aware I’m having a wave of self-doubt.”

That small linguistic shift matters. It separates you from the feeling and reminds you that this is something happening in your mind, not the full story of who you are. You don’t have to fight it, deny it, or believe it, just notice it.

From that space, you get to respond deliberately instead of reacting automatically. You can choose an action that aligns with your values, even while the emotion is still present. Defusion doesn’t erase the feeling, but it stops the feeling from running the show.

Now, I know that these distortions in self-talk may seem small, but they do add up. Over time, they shape how much trust you have in yourself, how much grace you offer yourself, and whether you view this journey as a fight or a practice.

When you start catching these moments, you give yourself back your agency. You regain the ability to be the author of your destiny.

C. How You Relate to Others

When it comes to nutrition and health, your internal dialogue isn’t just about you, it often involves what you think other people are thinking. How you relate to others plays a surprisingly big role in how you experience your own choices.

I’ve seen this countless times with clients. Someone makes a small choice around food or movement, but instead of just processing that decision, their mind immediately leaps outward. “What will they think?” “Everyone must have noticed.” “I’m the problem.”

These thoughts can be subtle, but they carry real emotional weight. They shape how you behave in social settings, how you view your own progress, and how much guilt or shame you attach to everyday actions. Let’s look at three common distortions that show up in this space.

Mind-Reading

This one often sounds like: “Everyone thinks I have no discipline.”

The problem here is that we don’t actually know what other people are thinking. But the human brain is wired for projection and social comparison. We imagine judgments where there may be none, filling in the blanks with our own insecurities.

I’ve worked with clients who avoided enjoying meals at social gatherings, because their mind filled in an entire imagined narrative about what everyone else must be thinking. That internal story can be more punishing than any real comment ever could be.

This is where Stoic philosophy offers a steady hand. The Stoics remind us that other people’s judgments are outside our control. What someone might think about what’s on your plate is not your responsibility. Your responsibility is your own action, your own choices, and your own alignment with your values.

Personalisation

Let’s imagine that you’re out at a restaurant with friends, you order dessert, and someone makes a passing comment about “being good” or “indulging.” Instead of recognising that as their story, your mind twists it into “I made it weird for everyone” or “I shouldn’t have ordered that.”

Here, a single personal action gets blown up into the idea that you’re responsible for the entire situation or everyone’s experience. It’s a kind of self-importance, but the painful kind, where blame gets internalised for things far beyond your control.

Philosophically, the antidote again comes from the Stoics: focus on your circle of control. You can control your own choices, not how others perceive them or how a moment unfolds for everyone else.

It’s important to recognise that diet culture amplifies personal blame. It teaches people to moralise food, to equate eating dessert with “being bad,” and to feel like any indulgence is a disruption to the social order.

But dessert is just dessert. You didn’t ruin anything.

Fallacy of Fairness

This one sounds familiar to almost everyone: “It’s not fair that others can eat anything and stay lean.”

This distortion compares your journey to someone else’s and judges the fairness of reality itself. But fairness, especially in health, body composition, and metabolism, has never been evenly distributed. Genetics, lifestyle history, environment, stress levels, and countless invisible factors shape outcomes in ways we can’t always see.

Philosophers like Epictetus and Emperor Marcus Aurelius would point out that life isn’t fair, and trying to make it fair in your head only adds suffering. The Stoic approach is to focus not on what’s “fair” but on what’s within your power (your habits, your values, and your response).

Someone else’s plate, body, or metabolism is not your measuring stick. Your responsibility is to align your actions with your own goals, not to win some imagined fairness game that doesn’t actually exist.

These kinds of distortions can shape how you move through the world. They can make social settings feel tense, make neutral choices feel like performances, and make comparison feel constant.

But once you name them for what they are, mental habits, not facts, you can loosen their grip. You can bring the focus back to where it belongs which is your own lane, your own choices, your own circle of control.

D. How You Predict the Future

A lot of the tension people feel around nutrition doesn’t come from the present moment, it comes from the future they imagine.

Our brains are storytellers. Long before anything happens, we predict it, rehearse it, and react emotionally as if it’s already real. This can be helpful when it leads to planning and preparation. But when those predictions are distorted, they become self-fulfilling traps.

I’ve seen this countless times in coaching where a client isn’t just dealing with what happened today, they’re bracing for tomorrow, next week, or the “inevitable failure” they’ve already decided is coming. These thought patterns often sound rational in the moment, but they often just aren’t true. Let’s break down three of the most common.

Fortune-Telling

This distortion sounds like: “I’ll mess up again.”

It’s when your brain treats a prediction as a fact. You’re not actually in the future yet, but emotionally, you’re already living there.

From a cognitive-behavioural perspective, this is where reframing really helps. Instead of treating the prediction as truth, you can turn it into a possibility.

- “I’ll mess up again” → “It’s possible I’ll face challenges again, but I can respond differently.”

Neuroscience backs this up. The brain often confuses what it imagines with what’s real, triggering emotional reactions to events that haven’t even happened. That’s why even the thought of “messing up again” can create guilt or anxiety before anything actually occurs.

When you bring awareness to that leap from prediction to certainty, you take back control of the narrative.

Catastrophising

This one shows up when a small event is blown up into a disaster: “One bad meal means I’ve failed completely.”

Catastrophising exaggerates the significance of setbacks, making a single moment feel permanent and global. It’s like turning a speed bump into a mountain.

Here, Stoic philosophy offers one of its most practical teachings: don’t inflate setbacks. A single deviation isn’t failure. It’s life. A bad day doesn’t define your health any more than a single good day guarantees it. The goal isn’t perfection, it’s consistency and adaptability.

When you can hold steady in the face of a wobble, you turn what could have been a downward spiral into a small detour that barely leaves a mark.

Control Fallacies

This distortion comes in two forms:

- “It’s all my fault.” (over-responsibility)

- “I have no control.” (powerlessness)

Both are extremes, and both are distortions. In reality, some factors are within your control, and some aren’t. This is where the Stoic dichotomy of control is such a powerful lens: separate what’s truly in your hands from what isn’t, and act only on the former.

From a behavioural design perspective, this often means focusing on your zone of influence. You may not control whether work gets stressful, but you can prep a balanced lunch in advance. You may not control your cravings, but you can shape your environment, like keeping nutrient-dense foods accessible or reducing friction around healthy habits.

These future-focused distortions don’t just predict the future, they create it. When you expect failure, you act accordingly. When you assume disaster, every bump feels fatal. When you believe you have either total control or none at all, you stop seeing the space where your choices actually matter.

But when you start catching these predictions for what they are, just stories your brain is creating, you reclaim your ability to respond flexibly and intelligently. You stop rehearsing failure and start practising agency.

Recognising Your Own Patterns (Before You React)

One of the most important skills you can build in your nutrition journey isn’t learning the perfect macro split or memorising calorie counts. It’s learning to notice your patterns before they run the show.

Cognitive distortions work fast. They’re quick, automatic, and often subtle. By the time you consciously realise what’s happening, your brain has already spun a story, and your emotions and behaviour have followed.

This is exactly what dual process theory describes: your fast brain reacts on autopilot, while your slow brain (the reflective part that makes deliberate choices) lags behind.

If you want to change the story, you have to create a moment of awareness before the distortion drives your response.

Spotting the Cues

Distortions rarely appear as neat, logical sentences. They often show up as emotional spikes like guilt after a meal, anxiety around food choices, shame after eating something “off plan,” or frustration when things don’t go perfectly. They can also hide in repeated regret behaviours like skipping meals after overeating, vowing to “start over Monday,” avoiding social situations around food, or silently beating yourself up for normal human choices.

Those emotional or behavioural patterns are signals. They’re the flashing dashboard lights of your mental habits.

Practical Strategies to Slow Things Down

When the fast brain fires, your job isn’t to be perfect, it’s to create a pause.

- Thought journaling can help you see the recurring themes in black and white instead of letting them swirl unexamined in your head.

- Post-meal reflections are a simple, low-stakes way to build awareness without judgment: “What was I feeling before and after that decision?”

- Naming distortions out loud, even quietly to yourself, is super effective here. Saying, “I’m noticing some all-or-nothing thinking right now”, turns an unconscious pattern into a conscious moment.

These “catch the thought” moments act like mental speed bumps. They don’t stop the distortion from showing up, but they slow it down long enough for you to choose a different response.

Stepping Back from the Thought

A core principle in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is that you are not your thoughts. You are the observer behind them. Thoughts come and go. Some are useful; some are noise. You don’t have to treat every one of them like a command.

This idea echoes a powerful line that is often attributed to Viktor Frankl: “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

Recognising your patterns creates that space. It’s the difference between reacting and responding, between running the same old loop and rewriting it.

You don’t have to eliminate every distortion to make progress. You just have to notice them early enough to steer instead of being steered.

Big Skills That Actually Work

By now, it should be clear that cognitive distortions aren’t just random thoughts, they’re deeply ingrained mental habits that shape how you act, how you feel, and how you relate to food, movement, and yourself. But the good news is, habits can be trained. Thought patterns can be reshaped.

The key isn’t to try to “out-discipline” these distortions. It’s to develop skills that make distorted thinking less powerful and wise action more automatic. These aren’t hacks or tricks, they’re well-established, evidence-based approaches I’ve used with clients to help them build more flexible, resilient mindsets around health.

These are the big skills that actually work to tackle the cognitive distortions holding your nutrition back.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Distortions often show up as automatic thoughts and fast, habitual interpretations that feel true in the moment but don’t fully reflect reality. Left unchecked, they shape your behaviour in unhelpful ways. Cognitive behavioural therapy can be a powerful framework for addressing these cognitive distortions that are sabotaging your nutrition goals.

One of the most effective CBT skills is cognitive restructuring. This involves three steps:

- Catch the distorted thought as it happens.

- Question it. Is it accurate, fair, or based on old patterns?

- Reframe it into a more balanced, reality-based statement.

For example:

- “I blew it.” → “I had one off-plan meal. I can make my next choice aligned with my goals.”

- “I always fail.” → “I’ve had setbacks before, but I’ve also recovered before.”

- “I have no discipline.” → “I struggled today, but one moment doesn’t define my capacity.”

This isn’t about forced optimism or sugar-coating reality. It’s about clearer thinking and noticing where your mind exaggerates, catastrophises, or personalises, and then replacing those distortions with something more accurate and useful.

Over time, this practice trains your brain to respond to challenges differently. A setback becomes data, not a verdict. That shift is often what separates a temporary slip from a downward spiral.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy offers a different way to work with the cognitive distortions that can derail your nutrition. Instead of arguing with your thoughts or trying to make them disappear, ACT teaches you to change how you relate to them.

A central skill here is defusion, which involves learning to separate yourself from your thoughts so they don’t control your behaviour. Normally, a thought like “I’ll never get this right” shows up and feels like a fact. With defusion, you create a little distance:

“I’m noticing the thought that I’ll never get this right.”

That small shift matters. You’re no longer inside the thought, you’re observing it. It’s still there, but it no longer has the same grip.

ACT also emphasises values-based action and making choices based on the kind of person you want to be, not on temporary emotions or distorted narratives. For example, if your value is taking care of your health, that value can guide your next choice, even if a part of your mind is yelling that you’ve “already failed today”.

This approach isn’t about silencing the storm in your head. It’s about steering your ship with a clear hand, even when the wind is against you. Over time, this builds resilience. Thoughts and feelings come and go, but your actions stay anchored to what matters.

Behavioural Design & Nudge Theory

Working on your thoughts matters, but the environment you move through shapes countless decisions before you even notice them. Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein popularised nudge theory, which is the idea that small, intentional design choices can make desired behaviours easier and less reliant on sheer willpower.

Instead of trying to force better choices through motivation alone, you engineer the path of least resistance to work in your favour.

- Lower friction for aligned choices:

- Keep nutritious food visible and easy to reach.

- Prep meals or snacks in advance so the “good choice” is the convenient one.

- Schedule workouts or walks ahead of time so they become part of your default day.

- Set reminders or cues for hydration and movement to reduce reliance on memory or mood.

- Increase friction for distortion-driven choices:

- Store impulse snacks out of sight or in a less convenient location.

- Create small “speed bumps” like a 5-minute pause before making certain food decisions.

- Unlink habits that drive automatic choices (e.g., no snacks by default while watching TV).

This isn’t about restriction or control, it’s about strategic design. When your environment supports your values, you don’t have to fight yourself as much.

Even on low-motivation days, these nudges help keep your behaviour aligned with your goals. This is about making the right thing the easy thing, rather than relying on perfect discipline.

Self-Compassion Training

A lot of distorted thinking thrives on judgments like “I should be better,” “I’m weak,” or “I failed again.” Harsh self-talk often disguises itself as “tough love,” but in reality, it shuts down learning. It narrows your focus to what went wrong and traps you in self-blame instead of helping you move forward.

Self-compassion doesn’t mean letting yourself off the hook. It means holding yourself accountable without cruelty. It’s the difference between berating yourself after a setback and talking to yourself like a good coach or friend would: with honesty, patience, and a focus on growth.

For example:

- Self-judgment: “I can’t believe I messed up again. I’m hopeless.”

- Self-compassion: “I made a choice that didn’t serve my goals. Why did that happen, and what can I try differently next time?”

This shift is powerful because it keeps you in the game. Shame pushes people to give up; curiosity pulls them toward understanding and adjustment.

Over time, self-compassion builds resilience. You can’t shame yourself into lasting change, but you can support yourself into it.

Support Structures

No one builds lasting habits in isolation. Motivation fluctuates, distorted thoughts creep in, and self-doubt has a way of getting louder when you’re on your own. Support structures, whether that’s a coach, a training partner, a group chat, or an online community, help keep your goals anchored when your inner voice starts spinning.

Support works because it provides what distorted thinking takes away: perspective. When your mind zooms in on a single mistake, someone else can help you zoom back out and remember the broader arc of your progress.

There are different kinds of support, and each plays a role:

- Accountability: a partner or coach who helps keep your actions aligned with your goals.

- Reality-checking: someone who can challenge black-and-white or catastrophic thinking when it shows up.

- Encouragement and structure: regular check-ins, shared habits, or group challenges that make consistency easier.

Support doesn’t have to be formal or complicated. It can be as simple as a text from a friend before a workout, a shared meal plan, or a community that normalises the ups and downs of the process.

Leaning on others isn’t a sign of weakness, it’s how sustainable change actually happens. When your mind gets tunnel vision, support helps you hold the bigger picture.

Philosophical Virtues

Long before modern psychology, Aristotle argued that a good life isn’t built on rigid rules or fleeting emotions, but on virtues. Qualities of character developed through deliberate practice. Virtues aren’t inborn traits. They’re trained, refined, and strengthened through everyday choices.

Three of these virtues are especially powerful when it comes to working with nutrition and cognitive distortions:

Temperance (Balance Over Extremes)

Temperance is the ability to find the middle ground between excess and deprivation. For Aristotle, this “golden mean” was the essence of virtue: not too much, not too little.

In a nutrition context, temperance might look like:

- Having dessert without framing it as “bad” or “good.”

- Eating enough to feel nourished without slipping into overrestriction.

- Adjusting your approach instead of swinging between rigid dieting and giving up entirely.

Temperance trains you to move away from the “I’ve ruined everything” mindset and toward steady, flexible consistency.

Courage (Showing Up When It’s Hard)

Courage isn’t the absence of fear or discomfort; it’s the willingness to act despite it. In nutrition work, this often means staying engaged when the process feels messy.

Courage might look like:

- Getting back on track after a setback instead of spiralling into self-criticism.

- Continuing your plan on days when motivation is low.

- Facing distorted thoughts head-on rather than avoiding them.

- Trying something new (like a healthier self-talk) even when part of you resists.

Courage keeps progress moving forward when perfectionism or shame would rather you quit.

Wisdom (Seeing Things Clearly)

Wisdom is the capacity to perceive reality without the filter of distortion. For Aristotle, practical wisdom (phronesis) was the virtue that guides all the others. It is knowing how to apply principles wisely in real life.

In a nutrition context, wisdom might look like:

- Recognising when an “I failed” story is just that; a story, not a fact.

- Identifying patterns over time instead of judging single moments.

- Making choices that align with your long-term values, not short-term impulses.

Wisdom brings perspective when your mind wants to catastrophise or moralise.

These virtues aren’t developed in extraordinary moments, they’re built in the ordinary. Every meal, every decision to keep going, every moment you choose clarity over distortion is a small rep in virtue training.

Over time, those reps compound. You become more balanced, more resilient, more able to respond to challenges with perspective instead of panic. That’s the power of virtue ethics: it turns abstract ideals into embodied habits.

All of these skills don’t silence distorted thoughts overnight, but they do change your relationship with them. Instead of being dragged around by old narratives, you learn to pause, reflect, and act with intention.

That’s where real, sustainable change comes from. You build the capacity to stay steady when your mind tries to pull you off course.

Putting It All Together

When you zoom out, the entire process we’ve been talking about really comes down to a simple flow. It’s not about silencing every distorted thought, or becoming some perfectly rational machine. It’s about building the kind of awareness and structure that lets you respond rather than react.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

Notice the thought → Name the distortion → Pause → Reframe or act by values.

That’s it.

You’re not trying to win a battle against your mind, you’re creating space between the thought and your action. A split second where you get to choose something different.

Say you catch yourself thinking, “I already messed up today.”

- Notice it. (“That’s a thought, not a fact.”)

- Name it. (“That’s all-or-nothing thinking.”)

- Pause. (Give yourself a breath before reacting.)

- Reframe or act by values. (“I can still make a good next choice. One moment doesn’t define me.”)

This flow works because it gives you your agency back. It shifts the power dynamic between your automatic thoughts and your deliberate actions. And that’s where change lives.

Ultimately, discipline isn’t really about control and willpower. It’s about design, awareness, and alignment.

- You design your environment to make the right choices easier.

- You build awareness so your patterns don’t run you on autopilot.

- You align your actions with your values, not with your fears, distortions, or cultural noise.

This is a quieter kind of discipline than Jocko or David Goggins screaming in your ear. Less about clenching your jaw through willpower, more about creating the conditions that support who you want to be.

A provocative question you can ask yourself along the way is this:

“What if your thoughts aren’t giving you truths… just options?”

A negative thought isn’t a command. A distorted belief isn’t a prophecy. They’re just options. Some are helpful, some aren’t. You get to choose which ones to act on.

So, the goal here is not erasing the thoughts, but choosing the response.

What Happens If We Don’t Do This Work

It’s tempting to think this kind of mindset work is optional and something “extra” you get to, after you’ve nailed the basics. But the truth is, if we don’t do this work, the consequences don’t just show up in our thoughts. They shape our entire relationship with food, our health, and ourselves.

When cognitive distortions go unchecked, they harden into patterns. Those patterns become the lens through which you see your body, your choices, and even your worth. Over time, that lens can become rigid and unforgiving.

You end up with a brittle relationship with food, where every choice feels loaded. Meals become moral tests instead of nourishment. A piece of cake isn’t just dessert, it’s “failure.” A salad isn’t just lunch, it’s “virtue.” Food stops being food and turns into a scoreboard.

This leads to emotional volatility around eating. Small choices start swinging your mood like a pendulum: pride when things go “right,” shame and guilt when they don’t. Instead of food being a steady part of life, it becomes an emotional minefield.

And slowly, short-term distortions start to undermine long-term health. When every slip-up feels like a collapse, consistency becomes fragile. Routines get abandoned. Effort turns into cycles of all-or-nothing. Real, sustainable progress requires flexibility, and distortions eat that flexibility alive.

On a broader level, when enough people are stuck in this loop, it feeds a culture where eating well becomes an act of shame, not self-respect. A world where people feel they have to “earn” their meals or “make up for” being human. Where the simple act of nourishing yourself is tangled up with guilt and moral judgment.

Ultimately, doing this work isn’t just about making better food choices. It’s about protecting your relationship with yourself. It’s about making sure your health practices are built on self-respect, not self-punishment.

Because without that foundation, even the best plan won’t work (for long).

The Cognitive Distortions Holding Your Nutrition Back: Conclusion

In the end, this work is about far more than nutrition.

When we talk about cognitive distortions, we’re not just talking about how you think about food. We’re talking about how you experience yourself. How you interpret your actions, how you relate to others, how you respond to challenges, and how you navigate the world. These mental patterns don’t just shape your diet; they shape your life.

And underneath it all sit some of the most timeless human questions:

- Control vs. chaos: How do we stay steady when we can’t control everything? How do we act wisely when the world doesn’t bend to our expectations?

- Flourishing vs. perfection: What does it mean to live well, not flawlessly, but fully and wisely?

- Meaning through choice: How do we create a meaningful life through the daily, often small, decisions that reflect who we want to be?

- Truth through practicality: What if “truth” isn’t a lofty ideal but something that proves itself useful in helping us live better?

These aren’t abstract philosophical debates. They show up when you decide what to eat on a stressful day, when you talk to yourself after a slip-up, or when you choose whether to spiral or self-correct.

Ultimately, clarity of thought is the foundation for wise action. Whether it’s a Roman emperor reflecting by candle light, a philosopher discussing virtue, a psychiatrist surviving unimaginable hardship, or a psychologist mapping the brain’s biases, the theme is the same.

Life is messy. The world is unpredictable. But we always retain a degree of agency in how we interpret, frame, and respond to what happens. Nutrition, though it seems mundane, is one of the most practical daily arenas where these philosophical and psychological principles come to life. Every food choice, every setback, every internal dialogue is a small echo of these timeless human struggles, and a chance to practice clarity, agency, and wisdom in real time.

The reality is that cognitive distortions are inevitable. You can’t get rid of them completely, and you don’t need to. The goal isn’t to become a perfectly rational being who never has a negative thought again.

The goal is to build skill. To notice distortions early, so they don’t run your day. To name them clearly, so they lose their power. To reframe or respond intentionally, so your choices align with your values instead of your fears.

When you approach nutrition with this kind of mindset, food stops being a battlefield and becomes a daily training ground for awareness and agency. Every snack, every skipped workout, every late-night craving, they’re not moral tests. They’re opportunities to practice the very skills that make a good life possible: patience, clarity, temperance, courage, and self-respect.

And this is where discipline is so often misunderstood. Real discipline isn’t about clenched-teeth control. It’s about design, awareness, and alignment.

- You design your environment and routines so that good choices are easier, and reactive choices are harder.

- You build awareness of your thought patterns so they stop blindsiding you.

- You act in alignment with your values, even when the old narratives show up, and they will show up.

This is what it means to practice wisdom in the everyday. Not in grand, dramatic moments, but in small, ordinary ones. In the space between stimulus and response, between the thought that appears and the action you choose.

One distortion caught might seem like a small thing. But every time you catch one, you’re reclaiming a little more of your agency. You’re untangling yourself from old mental habits and stepping into a way of eating, moving, and living that’s grounded in clarity instead of fear.

You’re choosing flourishing over perfection.

If you need more help with your own nutrition, you can always reach out to us and get online coaching, or alternatively, you can interact with our free content, especially our free nutrition content.

If you want more free information on nutrition or training, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

References and Further Reading

Byrne SM, Allen KL, Dove ER, Watt FJ, Nathan PR. The reliability and validity of the dichotomous thinking in eating disorders scale. Eat Behav. 2008;9(2):154-162. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.07.002 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18329593/

Lethbridge J, Watson HJ, Egan SJ, Street H, Nathan PR. The role of perfectionism, dichotomous thinking, shape and weight overvaluation, and conditional goal setting in eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2011;12(3):200-206. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.04.003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21741018/

Antoniou EE, Bongers P, Jansen A. The mediating role of dichotomous thinking and emotional eating in the relationship between depression and BMI. Eat Behav. 2017;26:55-60. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.01.007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28135621/

Volery M, Carrard I, Rouget P, Archinard M, Golay A. Cognitive distortions in obese patients with or without eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11(4):e123-e126. doi:10.1007/BF03327577 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17272943/

Herman CP, Polivy J, Esses VM. The illusion of counter-regulation. Appetite. 1987;9(3):161-169. doi:10.1016/s0195-6663(87)80010-7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3435133/

Mills JS, Palandra A. Perceived caloric content of a preload and disinhibition among restrained eaters. Appetite. 2008;50(2-3):240-245. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.007 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17888542/

Murphy R, Straebler S, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(3):611-627. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2928448/

Forman EM, Butryn ML, Manasse SM, et al. Acceptance-based versus standard behavioral treatment for obesity: Results from the mind your health randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(10):2050-2056. doi:10.1002/oby.21601 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27670400/

Warziski MT, Sereika SM, Styn MA, Music E, Burke LE. Changes in self-efficacy and dietary adherence: the impact on weight loss in the PREFER study. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):81-92. doi:10.1007/s10865-007-9135-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17963038/

Brenton-Peters J, Consedine NS, Roy R, Cavadino A, Serlachius A. Self-compassion, Stress, and Eating Behaviour: Exploring the Effects of Self-compassion on Dietary Choice and Food Craving After Laboratory-Induced Stress. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30(3):438-447. doi:10.1007/s12529-022-10110-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35731497/

Chand SP, Kuckel DP, Huecker MR. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. [Updated 2023 May 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470241/

Polivy J, Herman CP. Overeating in Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters. Front Nutr. 2020;7:30. Published 2020 Mar 19. doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.00030 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7096476/

Corns J. Rethinking the Negativity Bias. Rev Philos Psychol. 2018;9(3):607-625. doi:10.1007/s13164-018-0382-7 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6132407/

Keren H, Chen G, Benson B, et al. Is the encoding of Reward Prediction Error reliable during development?. Neuroimage. 2018;178:266-276. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.039 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7518449/

Dweck CS, Yeager DS. Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(3):481-496. doi:10.1177/1745691618804166 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6594552/

Yeager, D.S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G.M. et al. A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature 573, 364–369 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Dodos LA, Stenling A, Ntoumanis N. Does self-compassion help to deal with dietary lapses among overweight and obese adults who pursue weight-loss goals?. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(3):767-788. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12499 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8451927/