How much fat should you eat? Most people have unfortunately only been exposed to negative nutritional education on fat, and this has led to a lot of fear and misunderstanding of fat intake.

While we certainly want to make good choices around how we make up our fat intake, we shouldn’t be afraid of dietary fat. We do need to consume fat, it is impractical to try to eliminate it from the diet and trying to drastically reduce fat intake very often leads to a poor relationship with food.

So, the goal of this article is to give you all the information you need to allow you to answer the question of “how much fat should I eat?”

But I don’t want to just give you a single answer, I want to give you the information you need to actually be able to tailor your fat intake specifically to your needs (or the needs of your clients, as I know a lot of personal trainers, coaches and nutritionists read our content).

This article is still a part of the larger article series on how to set up the diet. So far in that article series, we have discussed setting up the calories for the diet and how much protein should you eat, and now we turn our attention to dietary fat intake.

The macronutrients are the nutrients you have to eat in big (macro) quantities in the diet, and they are the things that are actually contributing to the calorie content of the diet. The macronutrients are protein, carbohydrates and fats, although you could argue that alcohol, water and even fibre are all distinct macronutrients in their own right. Generally, when discussing the diet, we tend to just talk about protein, carbs, and fats, and that is mostly what I will be discussing, although I will briefly touch on some of the other macronutrients in this article series too.

Once you have an idea of what kind of calories you should be eating to achieve your goals, then you need to set specific macronutrient (protein, carbohydrate and fat) goals. Ultimately calorie balance is what determines whether you will lose weight or gain weight, however, macronutrients are what determines whether the weight you lose or gain is body fat or muscle (not entirely, but to a large extent) and there are also minimum targets (and optimal targets) for some of the macronutrients that we must eat to ensure we are healthy.

Most of you are likely looking to build/maintain your muscle mass, and also lose body fat, and I will be keeping this in mind when I discuss the targets. I am noting this, because there may be slightly different targets if you do no exercise at all, and I am assuming you are doing some exercise as that is part of our general recommendations (you can read our exercise content here).

Protein is generally the first macronutrient target we set, as protein is arguably the most important macronutrient from a health, performance and body composition perspective. But after we set our protein targets, we then look to set our fat targets. And by the end of this article, you will know exactly how much fat you should eat.

But before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Table of Contents

- 1 Understanding Dietary Fat

- 2 The Role Of Fats

- 3 Fats and Heart Health

- 4 How Much Fat Should You Eat?

- 5 Fat Distribution

- 6 Sources of Fat

- 7 Healthy Fat Meal Ideas

- 8 How Much Fat Should You Eat Conclusion

- 9 Author

Understanding Dietary Fat

You need to understand what fat is and why we need to consume it to make better choices around both how much fat to include in your diet and what types of fat you should include. So what is fat?

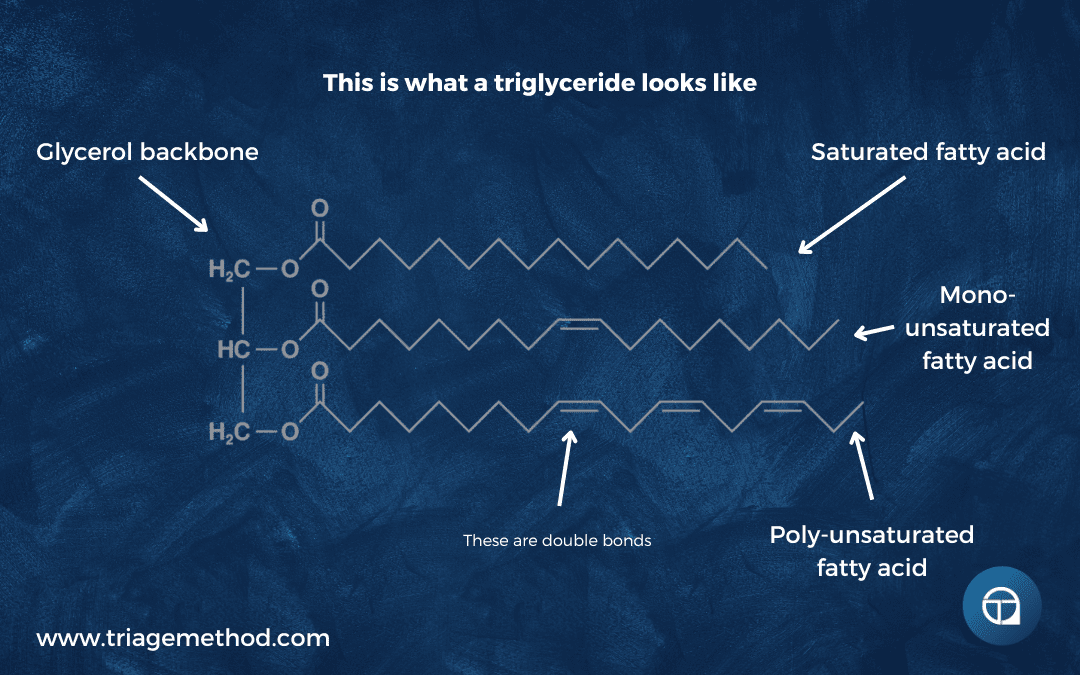

Most of you likely already know what fats are, as you have likely eaten a fattier cut of meat or consumed some sort of oil with your food, but you may not really know what fat actually is. For this discussion, we can make a very broad statement: dietary fat is composed predominantly of triglycerides.

These triglycerides are composed of a glycerol backbone and three individual fatty acids. These fatty acids can actually be quite diverse, as they can have different lengths (i.e. they can contain more or less carbon atoms) and they can also be saturated or unsaturated with hydrogen (if they are saturated, that simply means that all the carbons of the fatty acid has the maximum number of hydrogens bonded to it, and it contains no carbon-carbon double bonds).

Some foundational key terms are as follows:

- Fatty Acids: These are the building blocks of fats, consisting of a chain of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms attached. Fatty acids vary in length and degree of saturation (saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated).

- Triglycerides: The most common type of fat in the body and diet, triglycerides are made up of three fatty acid chains attached to a glycerol backbone. They serve as an energy source and are stored in adipose tissue.

- Cholesterol: A waxy, fat-like substance that’s essential for cell membrane structure, hormone production, and vitamin D synthesis. Cholesterol is found in animal products and is also produced by the liver.

- Phospholipids: These are like triglycerides but contain a phosphate group and two fatty acids instead of three. This structure makes them both fat- and water-soluble, which is why they are perfect for forming cell membranes.

Dietary fat is either saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated, based on the number of double bonds that exist in the fat’s molecular structure (with polyunsaturated having more than 1 double bond).

Saturated fats have no double bonds between carbon atoms, meaning each carbon is “saturated” with hydrogen atoms. They are typically solid at room temperature and found in animal fats, dairy, and tropical oils like coconut oil.

Unsaturated fats contain one (monounsaturated) or multiple (polyunsaturated) double bonds, making them liquid at room temperature. Found in plant oils, nuts, seeds, and fish, these fats are generally considered heart-healthy and may help reduce bad cholesterol levels.

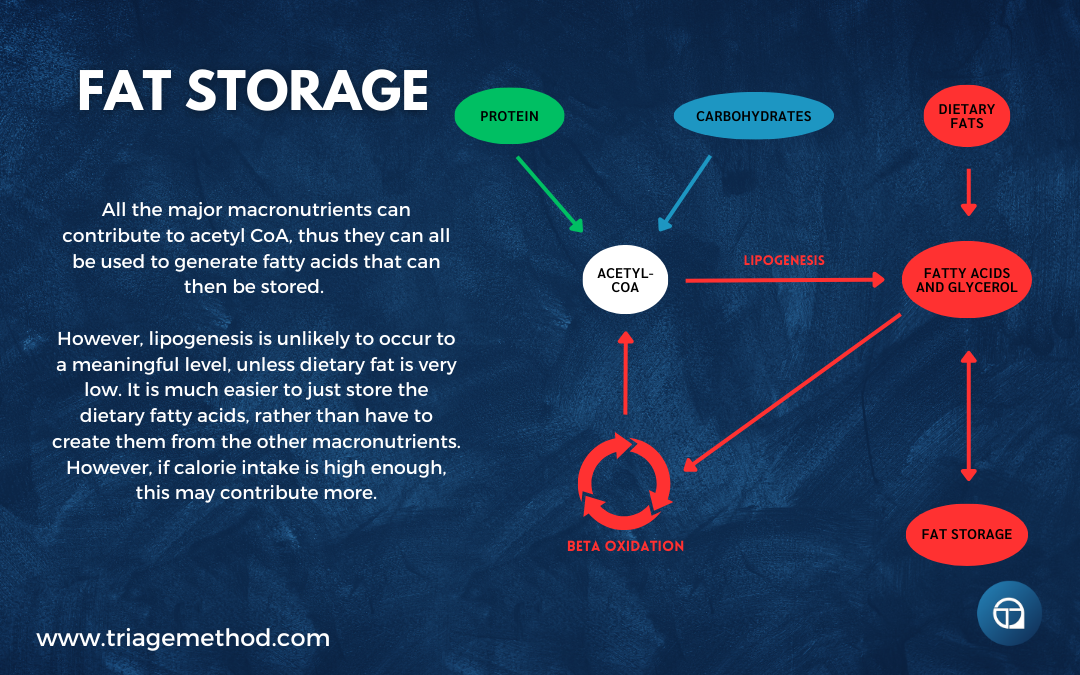

Now, your body can actually make fats if it needs to (from carbohydrates (and protein to a lesser extent) via pyruvate in a process called de novo lipogenesis), however, there are certain fatty acids that it can’t make.

The fats that the body can’t make are called essential fatty acids (EFAs) and they must be consumed in the diet. There is a lot of background stuff that we would have to discuss to fully understand the EFAs, but all you really need to know is that in the real world, when we discuss EFAs, we are discussing two specific fatty acids, EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid). These are also polyunsaturated fatty acids.

These are made (converted) from ALA (alpha-linolenic acid), which the body can’t make itself. However, the conversion is actually quite poor, so we are better off just consuming EPA and DHA directly.

Arachidonic acid (AA) is also an EFA (technically linoleic acid (LA) is the EFA, but it is converted to AA), but it is quite abundant in food (especially animal based foods), so we don’t need to worry about actively trying to include it in the diet, in the real world.

We will come back to these EFAs in a moment as they do influence our recommendations, but don’t feel like you have to remember all of this, as I am only discussing them to help you build a more complete picture.

There is a fourth category (other than saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated), trans fats. These are simply unsaturated fats with a slightly different “shape” than the traditional unsaturated fats. This causes trans fats to act more like saturated fats.

Not all trans fats are the same though.

Industrial trans fats are created through a process called hydrogenation, which solidifies vegetable oils to extend shelf life. It can be found in margarine, shortening, baked goods, and fried foods. These trans fats are harmful and are linked to increased inflammation, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.

However, there are naturally occurring trans fats. Small amounts of trans fats, like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), occur naturally in meat and dairy. These trans fats are generally not considered harmful and may even have some health benefits.

Industrial trans fats raise LDL (bad) cholesterol, lower HDL (good) cholesterol, increase inflammation, and significantly elevate the risk of heart disease and other chronic conditions. As a result, many countries, including the U.S., have banned or severely restricted the use of industrial trans fats in foods.

When reading labels, look for “partially hydrogenated oils,” as this generally indicates trans fats. Choosing whole, unprocessed foods, and avoiding fried and highly processed foods can really help reduce trans fat intake.

Now, you don’t need to memorise the biochemistry of all of this, however, it is important to understand that not all fats are exactly the same and they do different things in the body. We will touch on this all again in a moment, but for now, this basic understanding is all you need.

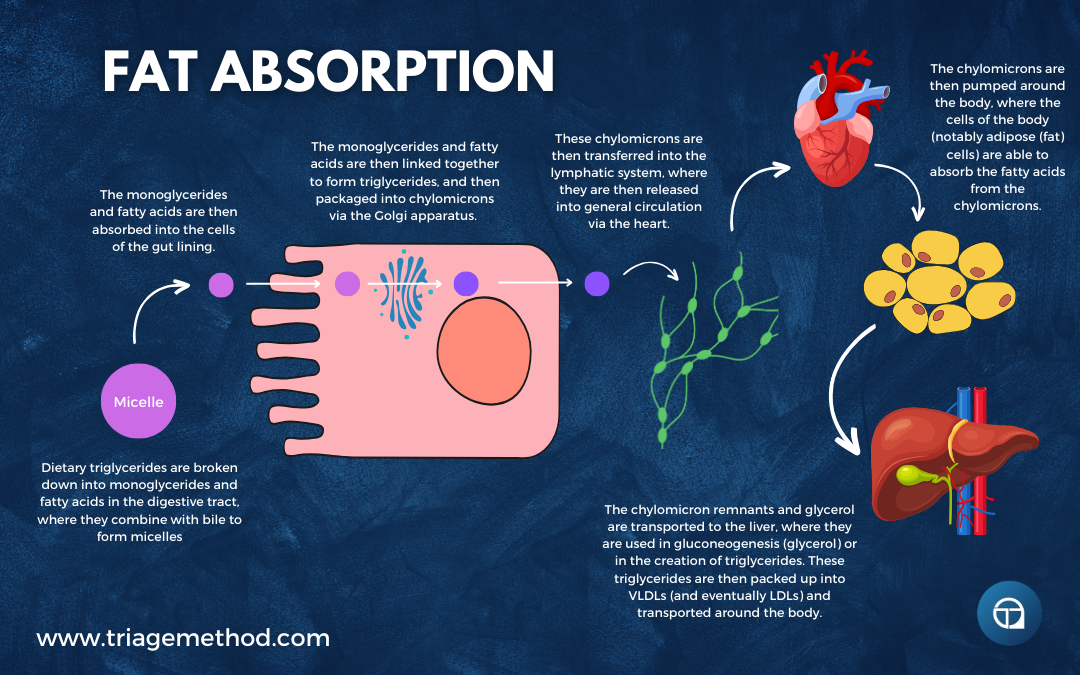

I don’t want to spend too long discussing the digestion of fats (although it is quite interesting because it isn’t exactly the same as other nutrients in the diet), but it is important to know what the body is doing with the various fats we eat and to also understand why we need to consume fats in the first place.

Very briefly, the digestion of fats begins in the small intestine, where bile from the liver emulsifies fats, breaking them into tiny droplets. Pancreatic lipase, an enzyme, then further breaks these droplets into their constituent fatty acids and monoglycerides. These molecules are absorbed by the intestinal cells, reassembled into triglycerides, and packaged into lipoproteins called chylomicrons, which transport fats through the lymphatic system and bloodstream to cells. This is where we see these fats used for their first major role in the body, energy utilisation or storage.

Now, with that little primer out of the way, we can actually discuss the role of fats and help you to better understand how much fat you should be eating.

The Role Of Fats

Fat has many roles in the body, and understanding these will help you to answer the question of “how much fat should you eat?”

Fats For Energy And Storage

One of the main things fats do is act as an energy substrate. The fats we eat are actually an incredibly dense source of fuel, and each gram of fat consumed contains roughly 9 calories per gram. Carbohydrates and proteins only contain 4 calories per gram, so fats are over double the calorie density of carbohydrates or proteins.

Fats can also be stored for future use in a much more efficient manner than carbohydrates (the other main energy substrate), as they can be neatly packed together as triglycerides. Whereas carbohydrates are stored as a very branching, splaying structure called glycogen, which also pulls in a lot of water molecules to store it (and thus can’t be packed tightly, and it ends up heavier than stored fat for an equivalent calorie amount).

Fats pack more of a punch when it comes to energy density and they can be more easily stored, so your body has evolved to be pretty damn good at storing them for future use. The ability to store fat has allowed humans to conquer the world, and our primate cousins can’t do this like we can.

Being able to store fat makes it much more likely that we will be able to survive periods of starvation, which was obviously very advantageous throughout our evolutionary history. However, this may not be as beneficial in the current era of abundance.

Now, it does bear repeating the fact that things are still governed by calories here, and just because fats are easily stored doesn’t mean they will be. Fat will only be stored when you are in a surplus of energy (i.e. a calorie surplus).

When you are in a surplus, your body will see that you have fats available and decide that it would be better to store the surplus of energy coming in, for future use. If you eat fat and you are in a calorie deficit, the body won’t decide to just store it. It will use the dietary fat as energy and it will also tap into your previously stored body fat to make up the deficit in energy.

It is important to understand that eating fat doesn’t mean you will gain body fat, eating a surplus of calories does. However, as fat has 9 calories per gram, it is easy to see how those calories can add up quickly and push you over the edge into a calorie surplus.

However, there is a slight downside to using fats as your energy source, and that is the fact that they require oxygen to be burned for energy. This means that fats don’t really fuel higher-intensity exercise all that well, and carbohydrates would be a much better fuel for this (as they can be used in anaerobic metabolism).

The only reason I mention this is that some people will do very low-carb, high-fat diets and still stay within their calorie and protein targets, but wonder why their workouts aren’t as good as they used to be.

We will discuss how much fat to include in the diet in a moment, and discuss how much carbs to include in a future article, but for now, just understand that a mixed diet (moderate carb and fat intake) is likely better for fuelling exercise.

The other reason I wanted to bring up the fact that fats need oxygen to be used for fuel is that some people will suggest that you must do low-intensity aerobic (i.e. using oxygen) cardio to lose fat, and this isn’t true. Your body is mostly using the aerobic system for everything you do, and if you simply eat in a deficit, your body will use the stored fats as needed.

You don’t need to do any specific fat-loss exercises or training protocols, you simply need to be in a calorie deficit.

Fats and Cell Structure And Function

Beyond fats being used as an energy substrate, fats (especially cholesterol and phospholipids) also play a structural role within the cells of our body. You see, every cell has a lipid (fat) membrane that encloses it, and well, keeps it together. The various small organelles within the cell, like the mitochondria and nucleus, also have lipid membranes.

Fats are also used in various other structural roles within the cells of the body, but we don’t need to dive too deep into this. All we need to know for now is that the fats we eat act as building blocks for these cellular structures.

Fats are also used as signalling (communication) molecules within the body or are required for the creation of certain signalling molecules. For example, there is a family of signalling molecules called the eicosanoids (which are made from AA (arachidonic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid)) which play a role in inflammation (among other things).

Many sex hormones (such as testosterone and estrogen) are made from fats (specifically cholesterol, which isn’t a triglyceride but does form part of the category of dietary “fats”).

Certain saturated fatty acids also serve as signalling molecules leading to a decrease in LDL receptor expression (and thus increase LDL (the “bad cholesterol”) in the bloodstream), whereas certain polyunsaturated fats serve to increase LDL receptor expression (and thus decrease LDL in the bloodstream).

There are many more examples, but the basic takeaway is that specific fatty acids do play a role in signalling in the body, and this does actually influence how we think about food selection.

Fats and Hormone Production

Dietary fat is more than just a source of energy, it’s a critical player in the production and regulation of hormones, particularly steroid hormones like estrogen, testosterone, and cortisol. You will very often see fat discussed as being vital for hormone production, but it is rarely explained why this is the case.

Sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone, which are vital for reproductive health, mood, and muscle growth, require cholesterol for synthesis. These hormones, which control everything from reproductive health to stress response and metabolism, are synthesised from cholesterol. Effectively, cholesterol is the building block for all steroid hormones, and it is also influenced by the fats we eat.

While the body can produce its own cholesterol, dietary fats (and dietary cholesterol) do play a role in maintaining healthy levels. If fat intake is too low, cholesterol availability can become limited, potentially impairing the production of hormones that rely on it.

But, as I noted, the body can actually produce the cholesterol it needs, so while this is often given as the rationale for why fats are important for hormones, it is unlikely to be the key reason. If you don’t consume any cholesterol in the diet, you will still likely produce all the cholesterol you actually need to make the sex hormones.

However, while the body can make cholesterol, dietary fats still play a crucial role in hormonal health. This is because certain types of fats (particularly saturated and monounsaturated fats) support the processes involved in hormone production, including the synthesis of cholesterol and the regulation of hormone-releasing signals.

For example, diets higher in saturated and monounsaturated fats are particularly effective in supporting testosterone production. These fats are believed to enhance the release of luteinising hormone (LH), which signals the testes to produce testosterone. Foods rich in these fats, such as eggs, meat, avocados, and olive oil, are associated with better testosterone synthesis compared to diets high in polyunsaturated fats, which in excessive amounts may actually suppress testosterone levels.

Low-fat diets are linked to higher sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels. SHBG is a protein that binds to testosterone in the bloodstream, rendering it less active. High SHBG means less free, bioavailable testosterone. On the other hand, higher-fat diets tend to reduce SHBG levels, increasing the amount of free testosterone available for use.

Healthy fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids and monounsaturated fats, also help manage cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. High cortisol levels can suppress sex hormone (e.g. testosterone) production due to the inverse relationship between these two hormones. By reducing inflammation, omega-3s and other anti-inflammatory fats can lower cortisol levels, creating a hormonal environment more favourable to sex hormone synthesis.

Conversely, a low-fat diet can sometimes lead to systemic inflammation and elevated cortisol, especially if the foods that displace the fats are of low quality. This can further disrupt testosterone production. Balancing fat intake can help control this cycle and support overall hormonal health.

Fats are also calorie-dense and provide sustained energy, particularly when carbohydrate intake is limited. Maintaining adequate energy levels is crucial for optimal hormone production. When the body lacks energy, it enters a catabolic state, which can suppress testosterone and other anabolic hormones.

Higher-fat diets can help ensure consistent energy availability, reducing stress on the body and promoting conditions that support hormone synthesis. For athletes and active individuals with high-calorie expenditure, this is especially important.

Essential fatty acids, omega-3s and omega-6s, play unique roles in hormone regulation. These fats are precursors to prostaglandins, hormone-like substances that control inflammation, blood flow, and other physiological processes. Omega-3s, found in fatty fish, chia seeds, and flaxseeds, are particularly anti-inflammatory and beneficial for balancing hormonal health, including menstrual regulation.

On the other hand, omega-6 fats, which are abundant in vegetable oils and processed foods, may contribute to inflammation when consumed in excess (this may not necessarily be due to the omega-6s themselves, and more so due to a lack of omega-3s and the types of foods that are eaten to have a high omega-6 intake). Maintaining a healthy balance between omega-3 and omega-6 intake is key to supporting hormonal and overall health.

Dietary fat also influences body fat stores (both due to contributing to calorie intake and in the actual quality and composition of the stored body fat), which produce leptin. Leptin is a hormone that regulates appetite and energy balance.

Leptin helps signal to the brain when the body has enough energy, affecting hunger and metabolism. Stable leptin levels, supported by adequate fat intake, are essential for maintaining metabolic health and preventing hormonal disruptions that can arise from extreme calorie restriction or imbalanced diets.

Ultimately, we want to consume sufficient fats, and we also want to consume the correct balance of fat types if we want to have optimal hormone production and hormonal balance.

Fats and Brain Health and Function

Dietary fats also play a role in supporting brain health and cognitive function. The brain is composed of nearly 60% fat, making it highly dependent on dietary fat for structure, function, and signalling.

Fats are essential for building and maintaining the brain’s cell membranes and myelin, a protective sheath that surrounds nerve fibres. Myelin, composed primarily of fatty acids, is critical for efficient signal transmission between neurons. The integrity of myelin sheaths impacts everything from learning to reflex responses, so adequate dietary fat supports these vital functions.

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), are integral to brain structure and function. DHA is the primary structural fat in the brain’s cell membranes, supporting neuron health, flexibility, and signalling.

Adequate DHA intake is linked to improved cognitive function, memory, and mood stability. Omega-3s also have neuroprotective effects, helping to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, both of which are associated with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Omega-6 fatty acids, found in foods like vegetable oils, nuts, and seeds, are also essential for brain health but in moderate amounts. These fats support brain function and development, but when consumed in excess relative to omega-3s, they may promote inflammation, which has been linked to mood disorders and cognitive decline.

Certain dietary fats are also involved in the production and function of neurotransmitters, the brain’s chemical messengers. For instance, omega-3 fatty acids help maintain serotonin and dopamine pathways, which are critical for mood regulation.

Low levels of omega-3s are associated with increased risks of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, while a diet rich in omega-3s supports mood stability and may reduce symptoms of depression.

Chronic brain inflammation is linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Omega-3 fatty acids, along with monounsaturated fats (found in olive oil, avocados, and nuts), have potent anti-inflammatory properties. These fats help reduce levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain, protecting neurons and promoting an environment conducive to brain plasticity and longevity.

Maintaining a balanced ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids (ideally close to 1:1 or 1:2) is often thought to be optimal for brain function and health. The typical Western diet tends to be high in omega-6 and low in omega-3.

You will see a lot of discussions about the optimal omega 3 to omega 6 ratio, but this may not be the right way to think about things. It is likely less about getting the ratio right and more about actually consuming sufficient omega-3 in the first place. Most people simply don’t eat enough omega-3s.

While some sources of omega-6s aren’t great food sources for a variety of reasons, I wouldn’t necessarily be blaming the problems on the omega-6s. The ratio is off because omega-3 intake is just insufficient. That doesn’t mean you should eat crappy food sources, not at all. But I wouldn’t be pinning the blame squarely on the omega-6s.

Dietary fats also help the body absorb fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K, which play various roles in brain health. For example, vitamin D is involved in cognitive function and mood regulation, and vitamin E has antioxidant properties that protect brain cells from oxidative damage.

In low-carb or ketogenic diets, dietary fats can be converted into ketones, an alternative energy source for the brain. Ketones are more efficient than glucose for brain cells and may enhance focus, mental clarity, and memory.

Ketogenic diets, which promote ketone production, are being explored for therapeutic effects on neurodegenerative diseases, seizure disorders, and traumatic brain injury.

So there are a variety of avenues by which fats play a role in brain health.

Dietary Fat and Vitamin Absorption

I noted it above, but dietary fat is essential for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, specifically vitamins A, D, E, and K. These vitamins play vital roles in various bodily functions, including immune health, bone strength, vision, and blood clotting. Because these vitamins are fat-soluble, they require the presence of dietary fat to be properly absorbed and utilised by the body.

Fat-soluble vitamins dissolve in fat, not water, so they rely on dietary fat to be absorbed in the small intestine. When dietary fats are consumed, bile (produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder) is released to emulsify these fats, breaking them down into smaller droplets.

Pancreatic enzymes further process these fat droplets, allowing the fat-soluble vitamins to be absorbed into the lymphatic system and then into the bloodstream. Without dietary fat, these vitamins are not effectively absorbed, potentially leading to deficiencies even when vitamin intake is adequate.

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is crucial for vision, immune function, cell growth, and skin health. It’s found in both animal sources as retinol (e.g., liver, dairy, eggs) and in plant sources as beta-carotene (e.g., carrots, sweet potatoes).

The body’s absorption of vitamin A is significantly enhanced in the presence of dietary fat. Adding healthy fats (like olive oil) to foods rich in beta-carotene boosts the body’s conversion of beta-carotene to retinol, the active form of vitamin A.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption, bone health, immune function, and mood regulation. While sunlight exposure enables the body to produce vitamin D, dietary sources (e.g., fatty fish, and fortified dairy) are also important.

Dietary fat is necessary for vitamin D absorption in the intestines. Without sufficient fat intake, vitamin D absorption can be limited, impacting calcium absorption and potentially leading to weakened bones and immune function. Including healthy fats like avocado, nuts, or fish oil with vitamin D-rich foods helps improve vitamin D uptake.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E acts as a powerful antioxidant, protecting cells from oxidative stress and supporting immune function, skin health, and heart health. Vitamin E is found in high-fat foods such as nuts, seeds, and vegetable oils.

Vitamin E, being inherently found in fatty foods, is readily absorbed in the presence of dietary fat. Adding healthy fats to foods rich in vitamin E can enhance its bioavailability. Without dietary fat, vitamin E may not be efficiently absorbed, reducing its antioxidant effects and benefits to the body.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is essential for blood clotting and bone health. It’s found in green leafy vegetables (vitamin K1) and fermented foods (vitamin K2).

Fat enhances vitamin K absorption, especially from vegetables. For example, pairing leafy greens with olive oil or avocado can increase vitamin K uptake. Inadequate fat intake can impair the absorption of vitamin K, potentially leading to clotting issues or weakened bones.

In summary, dietary fat is essential for the absorption of vitamins A, D, E, and K, each crucial for health and well-being. Including healthy fats in meals supports optimal nutrient absorption and prevents deficiencies in these essential fat-soluble vitamins.

In individuals on low-fat diets (or with fat malabsorption conditions), vitamin deficiencies may occur even with sufficient vitamin intake. So getting your fat intake dialled in is very important.

Dietary Fat and Satiety

Dietary fat plays a key role in promoting satiety, which is the feeling of fullness and satisfaction after eating. Unlike carbohydrates, fats are more calorie-dense and take longer to digest, which can help prolong feelings of fullness and reduce the likelihood of overeating. Here’s how dietary fat impacts satiety:

Fats are digested more slowly than carbohydrates because they require more complex processing in the digestive system. This slower digestion rate means that fats stay in the stomach longer, delaying gastric emptying and extending the feeling of fullness after a meal.

Because fat takes longer to move through the digestive tract, it has a stabilising effect on blood sugar levels, preventing rapid spikes and crashes that can lead to increased hunger and cravings.

Meals rich in fat contribute to delaying hunger by slowing digestion and stimulating the release of satiety hormones like cholecystokinin (CCK) and peptide YY (PYY). CCK is released when fats enter the small intestine and signals the brain via the vagus nerve to stop eating, reinforcing feelings of fullness. PYY, also released after fat-rich meals, further promotes satiety by slowing gastric emptying and reducing appetite.

Fats also add flavour and texture to foods, enhancing the eating experience and providing a sense of satisfaction that can help curb further cravings. Foods that lack fat may leave people feeling less satisfied, which can lead to increased food intake to compensate for the lack of fulfilment from the meal.

This aspect is particularly useful in weight loss efforts because meals with a moderate amount of fat can reduce the desire to snack or overeat later in the day, supporting better calorie control. This is one of those things that we get a lot of our fat loss clients to do (ensure adequate fat intake with each of their meals). It seems counterintuitive, as you often think you should be reducing fat (calories) to achieve fat loss, but this isn’t always the case. By ensuring the meals are actually tasty and satisfying, you are actually less likely to overeat by snacking later on.

Fats are the most calorie-dense macronutrient, providing 9 calories per gram, compared to 4 calories per gram from carbohydrates and protein. This high caloric density can provide a long-lasting energy source, which helps sustain energy levels throughout the day, particularly when there are longer intervals between meals.

This sustained energy release can prevent energy dips that often trigger hunger or cravings for quick energy sources, like sugary snacks, making fat a valuable component in meal planning for long-lasting satiety.

In summary, dietary fat contributes to satiety by slowing digestion, impacting hunger-regulating hormones, enhancing flavour, and providing sustained energy. Including healthy fats as part of a balanced diet can help with appetite control, reduce cravings, and support long-term weight management.

Practical Tips for Using Fat to Boost Satiety

- Include Healthy Fats in Each Meal: Ensure there are adequate sources of healthy fats, like avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, in your meals to support satiety and make meals more satisfying. You do still need to be aware of calorie intake though.

- Pair Fats with Protein and Fibre: Combining fats with protein and fibre-rich foods (like vegetables or whole grains) enhances satiety further, as fibre adds bulk and protein also slows digestion. A meal containing all three of these basically eradicates hunger and cravings for hours in most people.

- Avoid Over-Restriction of Fats: Extremely low-fat diets may leave individuals feeling less satisfied, leading to higher calorie consumption from other macronutrients or snacks. So don’t excessively lower calories from fats in an effort to lose weight, as it will often just result in increased food intake.

Fats and Heart Health

Before we answer the question of “how much fat should you eat?”, we need to just touch on fats impact on health, and specifically heart health. The quantity and type of fat you eat does have an impact on your overall health. We have already touched on this a bit while discussing the role of fat, but I do want to discuss fats and heart health specifically.

Now, we are generally of the opinion that the overall diet pattern is more important than singling out specific dietary components like fats or specific fatty acids (unless they are very harmful, like trans fats). We have also already extensively covered the health impacts of the diet in our article on why nutrition is important.

However, when it comes to health, specifically heart health, the quantity and type of fat you eat does have a pretty big impact. So, it is important to at least cover the basics here.

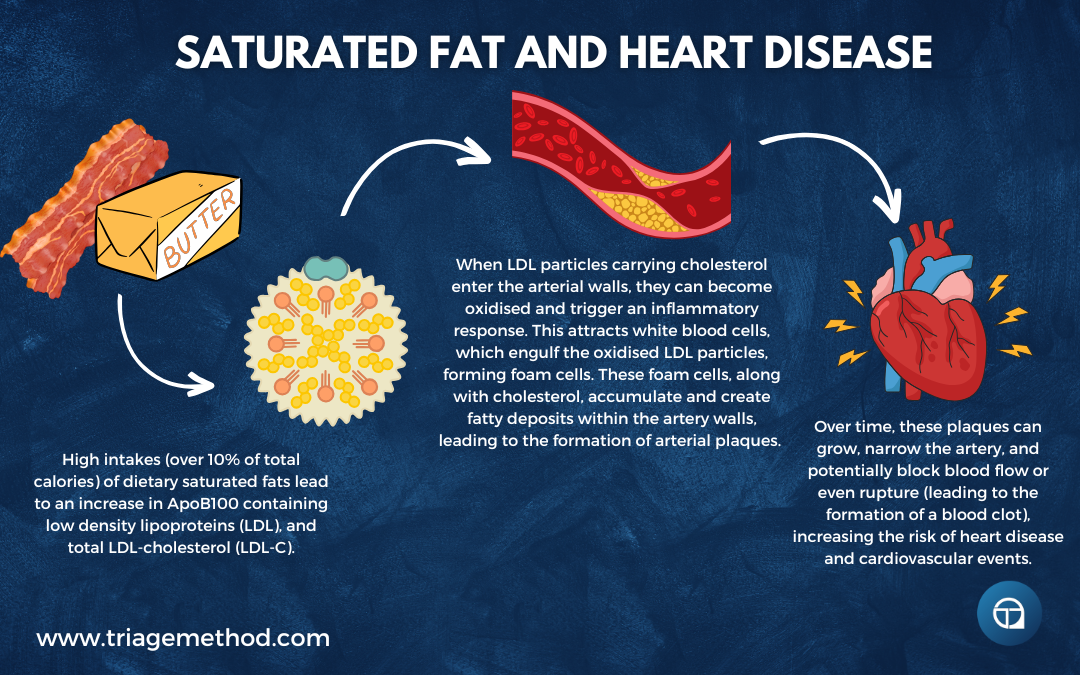

Traditionally, dietary fat was linked to heart disease, largely due to studies suggesting a correlation between high saturated fat intake, increased LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, and cardiovascular risk.

This led to the promotion of low-fat diets in the 20th century. However, this was misguided. Not all fats impact heart health equally and certain types of fat, like monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, may even support heart health.

The reality is that saturated fats increase LDL cholesterol levels, which can lead to plaque buildup in the arteries. Elevated LDL is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis and heart disease, as these plaques can narrow arteries, restrict blood flow, and increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

While not all LDL particles are equally harmful, elevated LDL remains a key indicator of cardiovascular risk, especially when paired with other factors like high blood pressure, inflammation, and low HDL levels.

As a result, while we do have to be a little bit more cautious about the overall quantity of fats we consume (especially if this leads to excess weight gain), what is more important is the quality of the fats we consume.

We will cover this in more depth in a moment, but the current guidelines recommend limiting saturated fats to about 10% of total daily calories while prioritising unsaturated fats. However, unlike what was previously recommended (reducing all fat intake), experts now emphasise the importance of replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats rather than reducing fat intake overall. Whole-food sources of saturated fats (such as dairy) are also often considered less harmful than processed sources, but moderation is still advised.

As a doctor specialising in heart health, and in my role as a coach, I always emphasise that the quality of fats in your diet is far more impactful than the total quantity. Saturated fats, especially from processed and fried foods, can elevate LDL cholesterol, contributing to plaque buildup in the arteries and increasing cardiovascular risk.

However, unsaturated fats, like those in olive oil, fatty fish, nuts, and seeds, can improve heart health by lowering LDL cholesterol and supporting anti-inflammatory pathways.

Ultimately, it’s not about eliminating fats entirely; it’s about choosing the right ones. By replacing saturated fats with unsaturated sources, you can protect your heart while still enjoying a balanced and satisfying diet.

– Dr. Gary McGowan

How Much Fat Should You Eat?

Now, we have been talking a lot about what fat does in the body, but what we are really here to discuss is how to set up your diet. So the question we need to answer is how much fat you need to eat.

Before we set our fat targets, we do generally advocate setting your calorie and protein goals first. After you have set your calorie and protein targets we generally move to setting a fat target next.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of controversy about what your fat targets should be. So before we get into our recommendations, I want to just briefly touch on what the major health organisations say about fat intake, and what was historically recommended.

Historical Dietary Fat Guidelines

1950s-1980s: Low-Fat Era

The belief that dietary fat, especially saturated fat, was a primary contributor to heart disease led to the promotion of low-fat diets.

Early guidelines, influenced by studies like the Seven Countries Study, emphasised reducing total fat intake to prevent cardiovascular disease.

The key recommendations were:

- Limit total fat intake to 30% of daily calories, with lower generally being seen as better.

- Limit saturated fat intake to less than 10% of daily calories.

- Minimise cholesterol intake to under 300 mg/day.

1980s-1990s: Increased Focus on Cholesterol

During this time, the emphasis on reducing dietary cholesterol intensified. Foods like eggs, butter, and red meat were often vilified for their cholesterol and saturated fat content.

Low-fat processed foods, often high in sugar and refined carbs, were promoted as “healthier alternatives”, despite growing concerns about their role in obesity and metabolic diseases.

Current Dietary Fat Guidelines

In recent decades, however, the recommendations have shifted to focus on fat quality rather than just quantity, recognising that different types of fats actually have varying effects on health. Unfortunately, a lot of people online seem to be unaware of the shifts in the dietary recommendations and they still discuss recommendations made in the 1950s as if they are the current recommendations.

Here’s what major organisations currently recommend:

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture)

The most recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020-2025) recommend:

- Total fat: No specific limit, but fat should account for 20-35% of daily calories for adults.

- Saturated fat: Less than 10% of daily calories.

- Trans fat: As low as possible (largely phased out of the food supply due to bans on partially hydrogenated oils).

- Emphasis on replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, particularly polyunsaturated fats, to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

- Dietary cholesterol: The previous cap of 300 mg/day has been removed, though the guidelines still recommend “as little as possible” in the context of a healthy diet.

WHO (World Health Organisation)

The WHO’s 2018 guidelines on dietary fats recommend:

- Total fat: 15-30% of daily calories.

- Saturated fat: Less than 10% of daily calories.

- Trans fat: Less than 1% of daily calories, emphasising the elimination of industrial trans fats globally.

- Focus on replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

American Heart Association (AHA)

The AHA guidelines emphasises fat quality and its impact on cardiovascular health:

- Total fat: No specific limit; align with general calorie needs and activity levels.

- Saturated fat: Less than 5-6% of daily calories for people at high risk of heart disease.

- Trans fat: Avoid entirely.

- Replace saturated fats with unsaturated fats, especially omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fats.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

EFSA provides similar recommendations:

- Total fat: 20-35% of daily calories.

- Saturated fat: As low as possible, while ensuring nutritional adequacy.

- Trans fat: As low as possible.

- Focus on unsaturated fats as the primary source of dietary fat.

National Health Service (NHS, UK)

The NHS aligns closely with other organisations:

- Total fat: 35% or less of daily calories.

- Saturated fat:

- 20g/day or less for women.

- 30g/day or less for men.

- Avoid trans fats and prioritise healthy fats from fish, nuts, and seeds.

While there are differences, if we look at all of these together, a pattern starts to emerge.

| Organisation | Total Fat | Saturated Fat | Trans Fat | Cholesterol | Key Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USDA (2020-2025) | 20-35% of daily calories for adults. | Less than 10% of daily calories. | As low as possible. | Previous cap of 300 mg/day removed, but “as little as possible” recommended. | Replace saturated fats with unsaturated fats, particularly polyunsaturated fats. |

| WHO (2018) | 15-30% of daily calories. | Less than 10% of daily calories. | Less than 1% of daily calories; eliminate industrial trans fats. | Not addressed specifically. | Replace saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats to reduce cardiovascular risk. |

| AHA | No specific limit; align with calorie needs and activity. | Less than 5-6% of daily calories for high-risk individuals. | Avoid entirely. | Not addressed specifically. | Prioritise unsaturated fats, especially omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fats. |

| EFSA | 20-35% of daily calories. | As low as possible, ensuring nutritional adequacy. | As low as possible. | Not addressed specifically. | Focus on unsaturated fats as the primary source of dietary fat. |

| NHS (UK) | 35% or less of daily calories. | 20g/day or less (women); 30g/day or less (men). | Avoid entirely. | Not addressed specifically. | Prioritise healthy fats from fish, nuts, and seeds. |

So how much fat should you eat?

How Much Fat Should You Eat?

A lot of these recommendations are set as percentage recommendations, which we really don’t like for various reasons. Most notably, we work with a lot of different people with a lot of different goals. Some of these people have incredibly low-calorie outputs (i.e., they burn very few calories per day), and some of these people have incredibly high-calorie outputs (i.e., they burn a lot of calories per day).

So, setting your fat target based on percentage can result in wildly divergent intakes, depending on your calorie expenditure and thus calorie needs.

The benefit of using percentages is that they tend to scale with output. So if you expend more, you will simply eat more calories from fat. However, the downside is that if you keep the percentage static, you can end up prioritising an energy source that isn’t as beneficial as other components of the diet (i.e. you can end up eating more fats when something like more carbohydrates may be more beneficial).

Conversely, if you are eating very little, you can actually end up not eating enough fats, as you may actually need to eat more than the static percentage to hit the baseline needs.

As a result, we much prefer using body weight (there are some caveats here, which I will explore in a moment).

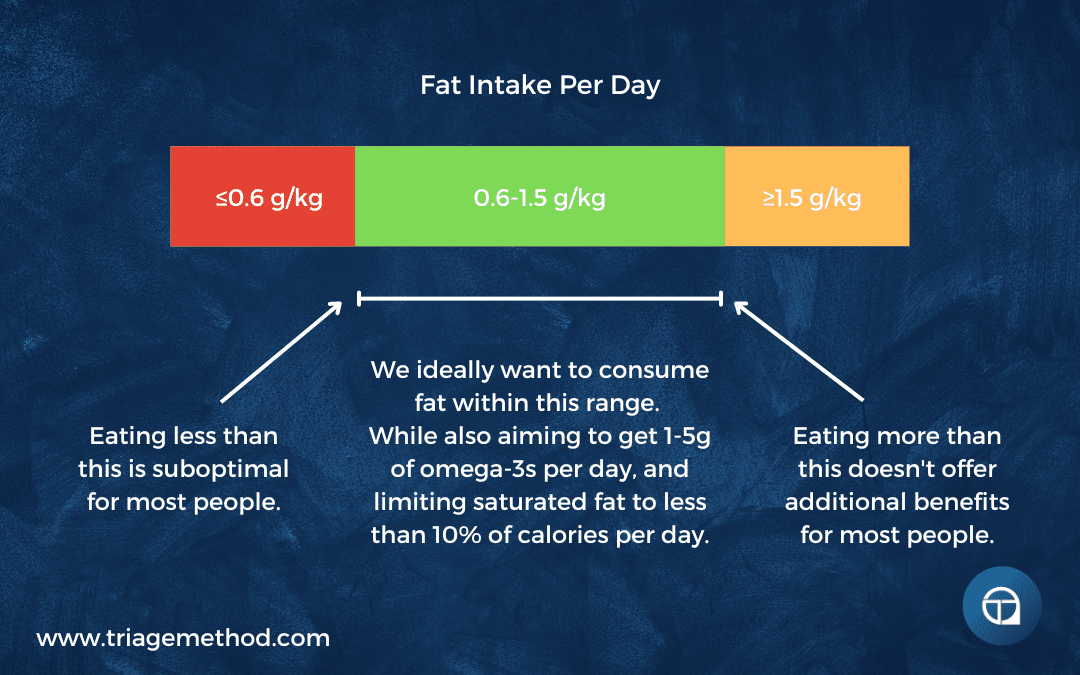

For various reasons, we like a range of 0.6-1.5 grams of fat per kilogram of body weight.

Practically, setting fat intake at roughly 0.8-1 gram per kilogram of body weight seems to work for the majority of people, as this means you aren’t hugely limited in your food choices but also that you aren’t just adding high-fat foods to try and hit your numbers.

In general, we don’t want to go too low with our fat intake, as this generally leads to increased hunger, excessive restriction in food selection choices, and it potentially reduces the overall healthfulness of the diet by negatively influencing food selection.

Most people tend to do well within that 0.6-1g per kg range, and most people don’t necessarily need more than this and most people don’t do well with less than this, so 0.8-1g per kg is a decent starting point.

So we want you to take your body weight in kilograms and multiply it by 0.8-1, and this will be your fat intake in grams.

So using a theoretical 70kg person, their fat intake will be between 56-70 grams per day.

Using the 2000 calorie maintenance we used previously, and accounting for the protein calories we set in the previous article on how much protein you need, using the 70g per day value we now have 866 calories left for carbohydrates, as every gram of fat is 9 calories (70 x 9 equals 630).

Fat Quality

However, we do also need to set some targets around how we actually make up this fat intake. We discussed quite a bit about the various roles of fat in the body, and if we want to ensure good health, we have to take this stuff into account when setting our targets. Certain profiles of fat intake seem to be better for health than others.

The first concern is in ensuring you do actually consume sufficient essential fatty acids (EFAs). As previously stated, in the real world, you likely only really need to concern yourself about your EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) intake. Generally, marine-derived food sources are higher in EPA and DHA than land-derived food sources, so most people should ideally be consuming some sort of seafood in their diet.

In general, we want to consume at least 1g of EPA/DHA per day, although there seems to be a dose-response curve with intake, with higher intakes being associated with better health outcomes (up to a point).

We generally recommend people consume 1-5g of EPA/DHA per day, with 0.5g being the bare minimum in healthy populations. Intakes of at least 2g per day seem to be the minimum threshold for where you start seeing tangible “additional” benefits to EPA/DHA (rather than just preventing deficiency).

You can get this from food, however, it can be difficult and thus fish oil supplements (or algal oil supplements, if you are plant-based) can be beneficial in hitting this target (for reference, 100g of salmon has ~1g of EPA/DHA, and most fish oil capsules have somewhere between 500-750mg of EPA/DHA per 1g capsule).

Now, saturated fat is also something we have to set a target for within our broader fat intake target(s). Higher intakes of saturated fat are associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk, and as such, we want to ensure we are not consuming too much. Saturated fat itself is not bad, and you certainly don’t need to completely eliminate it from the diet or demonise it, however, we do need to keep our intake in a good place (on average).

Eating foods that lead your fat consumption to be overly skewed to a higher proportion of saturated fat (eating greasy fried foods every day, putting butter on everything etc.) isn’t that great, and most people would do best consuming less than 10% of their calories from saturated fat.

Even lower than this may make sense if you are at an increased risk of heart disease, or already have elevated LDL or other heart disease risk factors (overweight, high blood pressure, smoking etc).

If you currently eat a lot of saturated fat, replacing it with monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat or complex carbohydrates is likely a good idea.

Using the example of 2000 calories as our maintenance from earlier, we would ideally consume less than ~22g of saturated fat per day.

Further to this, we would also be best served by eliminating trans fats from the diet, as they really don’t offer much and only increase the risk of heart disease. This isn’t something you will likely have to think about too much, as artificial trans fats have been largely eliminated from the food supply. However, you can still find them in countries that haven’t legally mandated their removal from the food supply. In general, you will see trans fats “hidden” as partially hydrogenated vegetable oil on the ingredients list.

As I mentioned cholesterol earlier, I just want to round out this discussion by making a note of intake recommendations for cholesterol. Dietary cholesterol doesn’t really need to be monitored too closely, as dietary cholesterol doesn’t seem to have a major impact on our levels of LDL or heart disease risk.

For most people, dietary cholesterol is not a major concern, as the body regulates its cholesterol production based on intake. However, for some sensitive or at-risk populations, such as those with genetic conditions like familial hypercholesterolemia or individuals with poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors, it may make sense to monitor and reduce dietary cholesterol intake. There’s generally no need to go out of your way to consume more cholesterol-rich foods, but you also don’t need to completely avoid dietary cholesterol (assuming you aren’t an at risk population).

Quick summary: Aim for 0.6-1g per kg of fats per day, with 1-5g of EPA/DHA per day, and less than 10% of total calories as saturated fat.

Now, while I did say that we generally like using grams per kilogram of body weight for our calculations, there are certain circumstances where this may not be appropriate.

If you are someone who is quite obese (and thus weigh a lot), this may put your fat targets much higher than your calorie targets would dictate.

This can make the diet quite poor as a result, as you are forced to eat a diet of basically all fat.

So, as a result, we also tend to suggest that there should be a cap on fat intake and the most practical way to do this is based on the percentage of calories.

For most people, setting a maximum intake cap of 35-50% of calories from fat does make sense. The exact cap is going to be dependent on a whole host of factors, but 35-50% seems to make sense in most cases.

Some people do like to eat a low carbohydrate diet, and as a result, you could argue that the cap should actually be higher. However, low carbohydrate or even ketogenic diets are not always the best option for the vast majority of people, and we are trying to set generalisable targets with this article series.

Ultimately, once you stay within your calorie targets and have a sufficient protein target, you shouldn’t go too wrong with things. Our ultimate diet calculator takes this stuff into account, but if you prefer to play around with the exact percentages yourself, you can use our calorie and macronutrient calculator or our macro percentage calculator.

If you really want to make things complicated, you could calculate your maximum fat intake based on your maximum natural potential lean body mass. This is difficult to actually calculate, but it is likely somewhere around your height in cm minus 100. So if you are 195cm like me, then your max lean mass is 95kg.

Your fat intake probably shouldn’t exceed 1.5x this number.

But for some people, this can still exceed their calorie allotment. So percentage-based maxes still make sense.

Low-Fat vs. High-Fat Diets

I know there are going to be people who read this article and who will suggest that the optimal fat intake is something else. These are usually people from either the low-fat or high-fat diet communities.

So, it makes sense to just touch on both of these to flesh out this discussion. The best way to do this is to just very briefly cover the pros and cons of each, but this discussion could actually be much longer if we want to truly flesh everything out.

Pros and Cons of Low-Fat Diets

Pros:

- May reduce calorie density, which can be useful for weight loss when combined with portion/calorie control.

- Historically linked to lower cholesterol and heart disease risk, though this depends on the quality of the remaining diet and saturated fat intake.

- Can be effective in reducing overall fat intake for individuals with specific medical conditions, like gallbladder issues.

Cons:

- Overemphasis on low-fat diets can lead to increased consumption of processed carbohydrates and sugars, contributing to metabolic issues like insulin resistance and weight gain.

- Insufficient fat intake can impair the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and lead to hormone imbalances. Fat is necessary for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). A diet too low in fat can lead to deficiencies, resulting in issues such as poor vision, weakened immunity, bone health problems, and oxidative stress.

- Some essential fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6) are crucial for brain and heart health (and health more broadly) and cannot be synthesised by the body, requiring adequate fat intake.

Ultimately, the belief that low-fat diets are inherently healthier is outdated and overly simplistic. While low-fat diets were historically promoted for heart health, modern research emphasises the importance of fat quality over quantity. Diets rich in healthy fats (like those in avocados, nuts, seeds, and fish) can improve cardiovascular health, while ultra-low-fat diets may lead to deficiencies in essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins.

Pros and Cons of High-Fat Diets

Pros:

- High-fat diets, like ketogenic diets, have been shown to improve satiety, reducing overall calorie consumption.

- They provide steady energy levels due to fat’s slower digestion and minimal impact on blood sugar levels.

- High-fat diets rich in healthy fats (monounsaturated and polyunsaturated, especially omega-3s) are linked to improved cholesterol profiles, reduced inflammation, and better brain health.

Cons:

- Overeating fats, especially saturated and trans fats, can increase the risk of heart disease and obesity if total caloric intake is not controlled.

- Can be difficult to sustain long-term for individuals who are from a carbohydrate-heavy culture, have food preferences for carbohydrates, or are engaged in sports where a higher carbohydrate intake would be better.

- Excessive fat intake can lead to inadequate consumption of other macronutrients, like protein and carbohydrates.

While fats are a vital part of the diet, overemphasising fat intake can reduce the intake of other important macronutrients:

- Carbohydrates: These are the body’s primary energy source, especially for high-intensity activities. Excess fat intake may reduce carbohydrate consumption, leading to “energy shortages”, particularly for athletes or active individuals.

- Protein: Protein is critical for muscle repair, immune function, and other bodily processes. A diet disproportionately high in fats may limit protein intake, impacting muscle recovery and overall health.

Balancing fat intake with carbohydrates and protein ensures the body has the nutrients it needs for energy, repair, and long-term health.

The belief that high-fat diets are somehow going to cure all ailments is also misguided and incorrect. There is a time and a place for both high and low-fat diets, but they generally shouldn’t be viewed as the baseline for the vast majority of people.

Ultimately, we generally recommend a more balanced approach to overall fat intake, but low-fat and high-fat diets can make sense in certain circumstances.

Fat Distribution

Is there a best time to eat fats? To an extent, no there isn’t a best time to consume your fats. Some people will do better with lower carbohydrates, and as a result higher fats, in the morning and vice versa in the evening. But a lot of this is just personal preference.

I generally recommend people just spread fat intake fairly evenly throughout the day, and if you are eating mainly whole foods it won’t be hard to get a good spread of fat throughout the day. If your diet consists primarily of whole foods (like nuts, seeds, avocados, eggs, dairy, meats and fatty fish), fat intake will naturally be distributed across meals, providing a steady source of energy and nutrients.

Fats are also quite satiating, as they slow digestion down a bit and create a more even release of nutrients into the blood. Fats slow digestion and contribute to prolonged satiety, creating a more gradual release of nutrients into the bloodstream. This makes fats especially useful to include in your meals throughout the day for avoiding sudden energy dips or hunger spikes.

So it is a good idea to spread your fat intake across the day as a baseline practice, although there may be times when you don’t want this slower release of nutrients. For example, if you are trying to get a quicker hit of energy and nutrients before your workout, you may want to have a smaller quantity of fats and prioritise carbohydrates at that meal. Since fats slow down digestion, they may not be ideal right before intense physical activity if quick energy is the goal.

Fat timing really doesn’t need to be complicated, just relatively evenly spread it across the day, and don’t prioritise it around the workout window.

Sources of Fat

Now you know how much fat you should be eating, and how to spread that out across the day. To finish off this article, I want to just discuss fat sources and then give you a few ideas for different meal ideas so you can see this stuff in practice.

I always find that when reading stuff like this article, one of the big issues is that it can seem quite removed from the reality of what you actually eat. After all, as humans, we eat food, not macronutrients. While there are obviously macronutrients in our food, this is generally not what we are thinking about when we eat. We are thinking about the foods themselves. So I always like to bring these discussions back to the real world, and I have found this is more impactful for my clients and I believe it leads to better results.

Anyway, there are a variety of sources of fat, and we can broadly break them down into animal fats, plant-based fats, and industrial/processed fats. Each has different pros and cons, and different use cases.

Animal Fats

Animal fats are primarily found in meats (beef, pork, lamb, and poultry), dairy products (butter, cheese, cream), fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), and eggs.

Nutritional Profiles and Types of Fatty Acids:

- Meat: Red meats, such as beef and pork, contain a mix of saturated fats and monounsaturated fats, along with a smaller percentage of polyunsaturated fats. They also provide essential nutrients like iron and vitamin B12.

- Dairy: Dairy contains a mix of saturated fats and monounsaturated fats. Dairy also provides short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a type of naturally occurring trans fat with potential health benefits.

- Fish: Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines are high in omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA), which are polyunsaturated fats known for their anti-inflammatory and heart-protective effects (including lowering triglycerides, reducing blood pressure, and improving overall cardiovascular health).

- Eggs: Eggs contain mostly monounsaturated and saturated fats, along with a smaller amount of polyunsaturated fats. They also contain choline, which is beneficial for brain health.

Plant-Based Fats

Common plant-based fat sources include nuts (almonds, walnuts etc.), seeds (chia seeds, flaxseeds, sunflower seeds etc.), oils (olive oil, sunflower oil etc.), avocados, and coconut.

Nutritional Profiles and Types of Fatty Acids:

- Nuts and Seeds: These are rich in polyunsaturated fats, particularly omega-6 fatty acids, along with some monounsaturated fats. Walnuts, chia seeds, and flaxseeds also provide omega-3 fatty acids in the form of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), though the body converts ALA to EPA and DHA at a low rate.

- Oils: Plant oils vary in fatty acid composition. Olive oil is high in monounsaturated fats, while sunflower and safflower oils are rich in polyunsaturated omega-6 fats. Coconut oil is unique among plant oils because it’s high in saturated fat (primarily medium-chain triglycerides).

- Avocados: Avocados are high in monounsaturated fats and contain smaller amounts of saturated and polyunsaturated fats, along with fibre and various vitamins and minerals.

- Coconut: Coconut oil and other coconut products are high in saturated fats, particularly lauric acid, which behaves differently in the body compared to longer-chain saturated fats.

Industrial Fats and Processed Fats

Industrial trans fats are created through a process called hydrogenation, which solidifies vegetable oils. These fats are commonly found in margarine, shortening, baked goods, and processed snacks. Trans fats raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, lower HDL (“good”) cholesterol, increase inflammation, and elevate heart disease risk.

Partially hydrogenated oils have largely been phased out in many countries due to regulations, but they are still found in some processed foods. Naturally occurring trans fats, found in small amounts in the meat and dairy of ruminant animals, do not have the same negative health effects and may even offer some benefits.

Processed foods like fried snacks, pastries, fast foods, and baked goods were historically high in trans fats, particularly from partially hydrogenated oils. These fats were widely used to enhance shelf life and texture but have been strongly linked to increased risks of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. Due to regulations in many countries, industrial trans fats have been largely eliminated from the food supply. However, some processed foods may still contain unhealthy fats, such as excess saturated fats and residual trans fats in unregulated regions or natural trans fats in small amounts from animal products.

What Fat Should You Be Eating?

We are generally advocates of getting a mix of fats from both animal and plant sources, and avoiding industrial/processed fats.

Consuming a mix of fats from both animal and plant sources ensures you get a balance of essential fatty acids, fat-soluble vitamins, and the health benefits associated with different types of fats.

Animal Fats

Animal fats provide a combination of saturated fats, monounsaturated fats, and small amounts of naturally occurring trans fats. While often debated in nutrition discussions, animal fats can be part of a healthy diet when consumed in moderation and sourced from high-quality foods.

Which Sources:

- Meats: Beef, pork, lamb, and poultry contain varying amounts of fat. Leaner cuts (e.g., chicken breast, pork tenderloin, sirloin) are lower in fat but still provide essential fatty acids.

- Fish: Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines are rich in omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA), which are known for their heart-protective and anti-inflammatory properties. These should be a regular part of your diet.

- Eggs: Eggs are a versatile source of fats, primarily monounsaturated and saturated fats, along with cholesterol, which is important for hormone production. They also provide choline, a nutrient essential for brain and liver health.

- Dairy: Milk, butter, cheese, and cream contain saturated and monounsaturated fats. Full-fat options can be included in moderation as part of a balanced diet, but leaner versions (e.g., low-fat milk, reduced-fat cheese) may be preferred if you’re managing calorie intake or cholesterol levels.

Plant-Based Fats

Plant-based fats are predominantly unsaturated fats, which include monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. These fats are known for their heart-health benefits, and anti-inflammatory properties.

Which Sources:

- Nuts: Almonds, walnuts, and pistachios are rich in monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats, including omega-3s (in the case of walnuts). They also provide protein, fibre, and antioxidants like vitamin E.

- Seeds: Chia seeds, flaxseeds, and sunflower seeds are excellent sources of polyunsaturated fats. Flaxseeds and chia seeds, in particular, are rich in alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), a plant-based omega-3 fatty acid.

- Oils:

- Extra Virgin Olive Oil: High in monounsaturated fats and polyphenols, olive oil is widely regarded as one of the healthiest fats. It supports heart health and reduces inflammation.

- Avocado Oil: Another rich source of monounsaturated fats, ideal for cooking at higher temperatures.

- Avocados: Packed with monounsaturated fats, fibre, and antioxidants, avocados are a nutrient-dense choice for heart and metabolic health.

A diet of these fat sources would be pretty darn good, and would allow you to eat a variety of foods, get a lot of nutrients in the diet, and ultimately enjoy the diet.

In practice, with our clients, we generally advocate choosing leaner cuts of meat, and consuming dairy, nuts, seeds, eggs and fatty fish. We generally don’t advocate adding oils to meals, outside of cooking. For cooking, we generally favour using olive oil (light olive oil for high heat, and extra virgin olive oil for lower heat cooking) or avocado oil (generally for high heat cooking).

Generally, this results in a diet that is below 10% saturated fat, predominantly monounsaturated fat, and a generally well balanced mix of omega 6s and omega 3s for the polyunsaturated component.

Ultimately, we want to consume a diet that results in fat intake coming predominantly from unsaturated fat. This means monounsaturated fats from stuff like olive oil, avocados, nuts, and leaner cuts of meat, and polyunsaturated fats from fatty fish, nuts, and seeds (with a focus on omega-3s).

This also potentially means consuming less butter, lard, full-fat dairy, and fatty cuts of meat, but not being afraid of these fat sources. They can still be a part of a healthy diet.

We want to ensure sufficient omega-3 intake through fatty fish, seeds, or algae-based supplements. Ideally, avoid excessive omega-6 fats from processed and fried foods. Most people will have to put a big emphasis on getting sufficient omega 3s, as most people under-consume them.

Industrial trans fats should be eliminated entirely. Although, naturally occurring trans fats in small amounts (from dairy or meat) are considered less harmful.

You will see a lot of discussion online about specific fats being healthy or unhealthy, and people act like the effects of these fats on your health is some unknowable thing. But the reality is, you can just get your blood work done and see how your diet is actually affecting you.

I know people that can maintain perfect blood work (both blood lipids and inflammatory markers) by eating a diet that is higher in saturated fats and composed of what would appear to be excessive omega 6s.

I also know people who despite doing everything absolutely perfectly with the diet, still aren’t able to get their blood work (especially blood lipids) within a healthy range.

So, while we (health and diet professionals) can pontificate about what an optimal diet might look like, the reality is that there is a high degree of individuality to this. But it isn’t something that is unknowable. You can get a very cheap blood test and more clearly see how your diet is actually affecting you. From this, you can then tweak the diet to your specific needs.

Healthy Fat Meal Ideas

Most people don’t need to actively think about adding fats to their meals, as they will simply come about as a byproduct of eating animal products, using cooking oils and perhaps also consuming dairy products.

However, it can be helpful to see a variety of different ways of how you could include some fats at different meals. I am going to be a bit “exotic” with things, as I don’t want to just repeat “fat from meat and cooking oil” a million different ways. So don’t think you have to consume these meals to eat a healthy diet, these are merely to illustrate that you do actually have a lot of different options available to you.

Healthy Fat-Containing Breakfast Ideas

Here are some healthy fat-containing breakfast ideas to help you incorporate more quality fats into your morning meals. These options offer a mix of monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and omega-3 fats, all of which support heart, brain, and overall health.

Avocado Toast with Eggs

- How: Spread avocado on whole-grain toast, add a sprinkle of salt and pepper, and top with a poached or fried egg.

- Why: Avocado is a rich source of monounsaturated fats, providing around 15g of fat per 100g. Pairing it with eggs gives you a well-rounded meal with both healthy fats and protein.

Chia Seed Pudding

- How: Mix chia seeds with almond or coconut milk and let it sit overnight. Top with fresh fruit and a handful of nuts for additional fats.

- Why: Chia seeds are high in omega-3 fatty acids. They also offer fibre and protein, making them a balanced breakfast option.

Greek Yogurt with Nuts and Seeds

- How: Add a handful of mixed nuts and seeds to Greek yoghurt for a creamy, crunchy, and nutrient-dense breakfast.

- Why: Adding nuts (like almonds, walnuts, or pumpkin seeds) to Greek yoghurt provides a dose of healthy fats, particularly monounsaturated and omega-3s (in the case of walnuts).

Smoothie with Nut Butter and Flaxseeds

- How: Blend nut butter, a tablespoon of flaxseeds, spinach, berries, and a banana with a milk of choice. You can add protein powder if you want more protein. The combination offers a nutrient-packed, filling breakfast with added fats.

- Why: Nut butters like almond or peanut butter contain healthy monounsaturated fats, and flaxseeds are a great source of plant-based omega-3s.

Smoked Salmon and Avocado on Whole-Grain Toast

- How: Layer smoked salmon and sliced avocado on whole-grain toast. Add a sprinkle of capers or fresh herbs for flavour.

- Why: Smoked salmon is rich in omega-3s, and avocado provides monounsaturated fats. Together, they create a heart-healthy, nutrient-rich breakfast.

Oats with Coconut Oil and Walnuts

- How: Prepare oats with milk or water, then stir in a teaspoon of coconut oil and top with walnuts and fresh fruit.

- Why: Coconut oil provides medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), a type of fat that’s quickly absorbed and used for energy, while walnuts add omega-3 fatty acids.

Breakfast Burrito with Avocado and Cheese

- How: Fill a whole-grain tortilla with scrambled eggs and/or beans, avocado slices, and a sprinkle of cheese. Add salsa or greens for extra flavour and nutrients.

- Why: Avocado and cheese both contain healthy fats, and adding eggs or beans increases the protein content.

Cottage Cheese with Almonds and Olive Oil Drizzle

- How: Top cottage cheese with a handful of almonds and a light drizzle of extra-virgin olive oil for a savoury twist on a classic high-protein breakfast.

- Why: Almonds and olive oil both provide monounsaturated fats, supporting heart health and satiety.

Eggs and Sautéed Spinach with Feta Cheese

- How: Scramble or fry eggs, then add to a bed of sautéed spinach. Top with crumbled feta cheese and a drizzle of olive oil.

- Why: Feta cheese adds healthy fats, while eggs provide a balance of fat and protein. Sautéing in a bit of olive oil further boosts the healthy fat content.

Tofu Scramble with Avocado and Sunflower Seeds

- How: Make a tofu scramble with veggies, then top with sliced avocado and a sprinkle of sunflower seeds.

- Why: Sunflower seeds contain healthy polyunsaturated fats, and avocado adds monounsaturated fats, making this a great plant-based fat-rich breakfast.

Almond Butter and Banana on Whole-Grain Toast

- How: Spread almond butter on whole-grain toast, then add banana slices and a sprinkle of chia seeds for extra omega-3s.

- Why: Almond butter is high in monounsaturated fats, while bananas add natural sweetness and potassium.

Quinoa Breakfast Bowl with Hemp Seeds and Avocado

- How: Prepare quinoa and top with avocado slices, hemp seeds, and a few veggies or a soft-boiled egg.

- Why: Hemp seeds provide a good balance of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, and quinoa adds protein and fibre.

Savoury Yogurt Bowl with Olive Oil, Nuts, and Cucumber

- How: Mix Greek yoghurt with a drizzle of olive oil, and top with sliced cucumber and a handful of nuts for a Mediterranean-inspired breakfast.

- Why: Olive oil provides heart-healthy fats, and nuts like almonds or pistachios add additional monounsaturated fats.

Egg Muffins with Cheese and Sun-Dried Tomatoes

- How: Bake mini egg muffins with shredded cheese, chopped sun-dried tomatoes, and spinach for a breakfast rich in healthy fats.

- Why: Cheese adds fat for satiety, while sun-dried tomatoes provide antioxidants.

Coconut Yogurt with Flaxseeds and Berries

- How: Top coconut yoghurt with flaxseeds and berries for a creamy, nutrient-dense, high-fat breakfast.

- Why: Coconut yoghurt is naturally high in fat and provides a dairy-free alternative. Adding flaxseeds provides omega-3s.

Healthy Fat-Containing Lunch Ideas

Here are some healthy fat-containing lunch ideas that incorporate a variety of nutrient-dense fats, including monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and omega-3 fatty acids, to keep you satisfied and energised through the afternoon.

Salmon Salad with Avocado and Mixed Greens

- How: Serve a grilled or baked salmon fillet over mixed greens with sliced avocado, cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, and a sprinkle of seeds. Drizzle with olive oil and balsamic vinegar.

- Why: Salmon is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and avocado provides monounsaturated fats. Together, they create a heart-healthy and filling lunch.

Mediterranean Grain Bowl with Hummus and Olives

- How: Layer quinoa or farro with hummus, kalamata olives, cucumber, cherry tomatoes, and feta cheese. Top with a drizzle of olive oil and a sprinkle of herbs for added flavour.

- Why: Hummus and olives contain healthy fats from tahini and olive oil, providing both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Chicken and Avocado Wrap with Spinach and Sunflower Seeds

- How: Fill a whole-grain wrap with grilled chicken, avocado slices, fresh spinach, and a sprinkle of sunflower seeds. Add a dollop of Greek yoghurt for creaminess.

- Why: Avocado provides monounsaturated fats, and sunflower seeds add polyunsaturated fats, and vitamin E.

Tuna Salad with Olive Oil and Walnuts

- How: Mix canned tuna with a bit of olive oil, chopped celery, walnuts, and herbs. Serve over lettuce or in a whole-grain wrap.

- Why: Tuna provides omega-3 fatty acids, while walnuts add additional omega-3s and polyunsaturated fats.

Egg and Avocado Stuffed Bell Peppers

- How: Hollow out bell pepper halves and fill with scrambled eggs and avocado. Sprinkle with chives or a bit of cheese if desired.

- Why: Eggs and avocados are both rich in healthy fats, and bell peppers add fibre and vitamins.

Tofu and Avocado Sushi Rolls

- How: Make sushi rolls using nori sheets, cooked sushi rice, avocado, and tofu slices. Serve with a side of soy sauce and pickled ginger.

- Why: Avocado offers healthy monounsaturated fats, while tofu adds plant-based protein and fats.

Quinoa Salad with Feta, Pumpkin Seeds, and Olive Oil

- How: Combine cooked quinoa with diced cucumbers, cherry tomatoes, crumbled feta, and pumpkin seeds. Dress with olive oil and lemon juice.

- Why: Pumpkin seeds are rich in polyunsaturated fats, including omega-6, and olive oil provides monounsaturated fats.

Grilled Chicken Salad with Avocado and Almonds

- How: Toss mixed greens with grilled chicken breast, avocado slices, sliced almonds, and a light olive oil dressing.

- Why: Avocado and almonds add healthy fats, while chicken provides protein, making this a balanced, satisfying meal.

Lentil and Walnut Salad with Spinach and Olive Oil Dressing

- How: Mix cooked lentils with fresh spinach, chopped walnuts, and an olive oil and balsamic dressing. Add crumbled goat cheese if desired.

- Why: Walnuts provide omega-3s, and olive oil contributes monounsaturated fats for heart health.

Stuffed Avocado with Tuna or Chickpeas

- How: Halve an avocado and fill it with a mixture of canned tuna or mashed chickpeas, diced celery, and a bit of olive oil or Greek yoghurt.

- Why: Avocado provides monounsaturated fats, and tuna or chickpeas add protein and omega-3s (in the case of tuna).

Whole-Grain Pasta Salad with Pesto and Pine Nuts

- How: Toss cooked whole-grain pasta with a spoonful of pesto, cherry tomatoes, and baby spinach. Add grilled chicken or chickpeas for extra protein.

- Why: Pesto, typically made with olive oil and pine nuts, is rich in monounsaturated fats and vitamin E.

Chickpea Salad with Avocado and Tahini Dressing

- How: Combine chickpeas, chopped cucumber, tomatoes, and avocado. Dress with a mixture of tahini, lemon juice, and a bit of water to thin it out.

- Why: Tahini is rich in polyunsaturated fats, and avocado provides monounsaturated fats, creating a creamy and filling dressing.

Greek Salad with Feta, Olives, and Olive Oil

- How: Mix cucumbers, tomatoes, red onions, olives, and feta cheese. Drizzle with olive oil and a sprinkle of oregano.

- Why: Olive oil and olives are excellent sources of monounsaturated fats, and feta adds a bit of protein and calcium.

Egg Salad with Avocado and Olive Oil

- How: Mash hard-boiled eggs with diced avocado and a small drizzle of olive oil. Serve on whole-grain toast or over leafy greens.

- Why: Eggs provide both protein and fats, while avocado and olive oil add heart-healthy monounsaturated fats.

Shrimp and Avocado Bowl with Brown Rice

- How: Layer cooked brown rice, shrimp, avocado slices, and a handful of shredded carrots. Top with sesame seeds and a squeeze of lime.

- Why: Shrimp is a lean protein, while avocado provides monounsaturated fats and fibre, creating a balanced, nutrient-rich bowl.

Cauliflower Rice Bowl with Sautéed Tofu and Cashews

- How: Sauté tofu cubes with veggies, then serve over cauliflower rice. Top with cashews and a drizzle of tahini or sesame oil.

- Why: Cashews offer monounsaturated fats, while tofu provides a mix of protein and fat, making this a balanced plant-based option.

Turkey and Avocado Lettuce Wraps with Hummus

- How: Use large lettuce leaves as wraps, and fill them with sliced turkey breast, avocado, and a spread of hummus. Add sliced cucumber and shredded carrots for extra crunch.

- Why: Avocado and hummus provide healthy fats, and turkey offers lean protein.

Baked Sweet Potato with Almond Butter and Chia Seeds