How much protein should you eat? I couldn’t tell you the number of times I have been asked this across my career in the health and fitness industry. Protein is one of those nutrients that really seems to confuse people, likely due to the sheer amount of poor information circulating online about protein. The goal of this article is to give you all the information you need to allow you to answer the question of “how much protein should I eat?”

But I don’t want to just give you a single answer, I want to give you the information you need to actually be able to tailor your protein intake specifically to your needs (or the needs of your clients, as I know a lot of personal trainers, coaches and nutritionists read our content).

But, this article is still a part of the larger article series on how to set up the diet. So far in that article series, we have only focused on setting up the calories for the diet, so I also need to introduce the concept of macronutrients. Then over the next few articles, show you how to set targets for each of the macronutrients.

The macronutrients are the nutrients you have to eat in big (macro) quantities in the diet, and they are the things that are actually contributing to the calorie content of the diet. The macronutrients are protein, carbohydrates and fats, although you could argue that alcohol, water and even fibre are all distinct macronutrients in their own right. Generally, when discussing the diet, we tend to just talk about protein, carbs, and fats, and that is mostly what I will be discussing, although I will briefly touch on some of the other macronutrients too.

Once you have an idea of what kind of calories you should be eating to achieve your goals, then you need to set specific macronutrient (protein, carbohydrate and fat) goals. Ultimately calorie balance is what determines whether you will lose weight or gain weight, however, macronutrients are what determines whether the weight you lose or gain is body fat or muscle (not entirely, but to a large extent) and there are also minimum targets (and optimal targets) for some of the macronutrients that we must eat to ensure we are healthy.

Most of you are likely looking to build/maintain your muscle mass, and also lose body fat, and I will be keeping this in mind when I discuss the targets. I am noting this, because there may be slightly different targets if you do no exercise at all, and I am assuming you are doing some exercise as that is part of our general recommendations (you can read our exercise content here).

Protein is generally the first macronutrient target we set, as protein is arguably the most important macronutrient from a health, performance and body composition perspective. But before we discuss how much protein you should eat, we must first discuss a little bit about why protein is important.

But before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Table of Contents

- 1 The Role of Protein

- 2 How Much Protein Should You Eat

- 3 Factors That Influence Protein Needs

- 4 Protein Distribution

- 5 Sources of Protein

- 6 How Much Protein Should I Eat Conclusion?

- 7 Author

The Role of Protein

The goal of this article isn’t to teach you everything there is to know about the biochemistry of protein. The goal is to help you to understand how much protein you should be eating. However, it does help to have at least some background knowledge of what protein actually is and why it is important. So I will just touch on a few things here, but don’t think you need to memorise or learn it all to understand how to set up your diet.

Proteins are these large molecules that are made up of individual amino acids. Proteins are used to make all the different things that you are made of, from your skin to your liver, your heart to your hair, and everything in between, they all use proteins. Protein is often considered to be the building block of life. However, it isn’t just a building block, proteins (and amino acids) also serve as signalling molecules within the body.

For example, insulin is a protein, and it plays a very important role in human health and metabolism in general. The various enzymes your cells use to carry out the chemical reactions they need to carry out are also proteins. Your immune system only works because of proteins (antibodies). Your muscles are made of proteins. When we talk about genetics, what your genes are actually doing is telling your body which proteins to make. Proteins are vital to life as we know it.

Your body is constantly building and breaking down protein structures, as they get old and wear out, new structures are required and old structures need to be repaired. There is a constant turning over of these proteins, and they get broken down into their individual amino acids, so they can then be reused. However, the system isn’t perfect and the processing of protein does result in some products being created that the body can’t really deal with, so it excretes them.

Furthermore, the body can’t create all the amino acids it needs to build all the various proteins it needs, and if even one amino acid is limited, then the protein can’t be made (the way proteins are created is like adding lettered beads onto a string to spell a word, so you can’t skip one and come back to it later). As a result, you need to consume protein each day to ensure you remain in a positive protein balance (i.e. you are retaining more protein than you excrete each day) and you also need to ensure that you are consuming all of the amino acids that the body can’t make itself. These amino acids are called the “essential amino acids” (EAAs).

For the average adult, the recommended daily intake of each essential amino acid is as follows (based on the WHO/FAO/UNU guidelines per kilogram of body weight):

- Histidine: 10 mg/kg/day

- Isoleucine: 20 mg/kg/day

- Leucine: 39 mg/kg/day

- Lysine: 30 mg/kg/day

- Methionine + Cysteine: 15 mg/kg/day (combined sulfur-containing amino acids)

- Phenylalanine + Tyrosine: 25 mg/kg/day (combined aromatic amino acids)

- Threonine: 15 mg/kg/day

- Tryptophan: 4 mg/kg/day

- Valine: 26 mg/kg/day

For an average adult weighing 70 kg, the daily intake requirements would be:

- Histidine: 700 mg/day

- Isoleucine: 1,400 mg/day

- Leucine: 2,730 mg/day

- Lysine: 2,100 mg/day

- Methionine + Cysteine: 1,050 mg/day

- Phenylalanine + Tyrosine: 1,750 mg/day

- Threonine: 1,050 mg/day

- Tryptophan: 280 mg/day

- Valine: 1,820 mg/day

While there are no universally standardised EAA recommendations specific to exercise, studies suggest that athletes or active individuals may benefit from consuming around 20–50% more protein than sedentary individuals. This increased protein intake also likely means a higher intake of EAAs.

For active individuals, the general daily intake for EAAs might be as follows:

- Histidine: 12-15 mg/kg/day

- Isoleucine: 25-30 mg/kg/day

- Leucine: 45-55 mg/kg/day

- Lysine: 36-40 mg/kg/day

- Methionine + Cysteine: 18-20 mg/kg/day

- Phenylalanine + Tyrosine: 30 mg/kg/day

- Threonine: 18-20 mg/kg/day

- Tryptophan: 5-6 mg/kg/day

- Valine: 30-35 mg/kg/day

For an active individual weighing 70 kg, the intake might look like this:

- Histidine: 840–1,050 mg/day

- Isoleucine: 1,750–2,100 mg/day

- Leucine: 3,150–3,850 mg/day

- Lysine: 2,520–2,800 mg/day

- Methionine + Cysteine: 1,260–1,400 mg/day

- Phenylalanine + Tyrosine: 2,100 mg/day

- Threonine: 1,260–1,400 mg/day

- Tryptophan: 350–420 mg/day

- Valine: 2,100–2,450 mg/day

Now, you don’t need to go excessively out of your way to ensure you consume these essential amino acids, as they are in decent quantities in meat, fish, eggs and dairy, which will generally be the main protein sources for most people. However, if you eat a diet that doesn’t include meat, fish, eggs and dairy, or if you eat these in very limited quantities, then you will have to pay more attention to your amino acid intake.

As we are talking about amino acids, it is also important to understand that while proteins can serve as signalling molecules (remember insulin), so too can certain amino acids. You don’t need to really go down the rabbit hole of understanding this, however, it bears noting that a particular amino acid, leucine, is an important signalling molecule for muscle building and growth in general.

So those concerned about muscle building should ensure that they are consuming sufficient leucine at each meal (roughly 3g is enough), and if you choose meat, fish, eggs or dairy as your protein source, this is usually easy enough to do. But as before, if they aren’t staples in your diet, then you may need to pay more attention to this. The muscle-stimulating effects of leucine do have a refractory period (basically a rest period) before it can stimulate again, and this informs our protein timing recommendations (we will discuss these more below). In general, if we want to maximise muscle building/retention, we want to try and spread protein intake out throughout the day, with 3-5 protein feedings fairly evenly spaced across the day.

Protein can also be used as an energy source, although this isn’t the body’s preferred energy source. Dietary protein does also have a significant “thermic effect of feeding” (TEF), and you do have to spend some more calories to actually digest and assimilate protein. So if you were to eat the exact same amount of calories as you do now (let’s assume it is maintenance calories), but you just started consuming more protein, you would actually end up burning more energy and be in a slight deficit. Protein is also very satiating, meaning it keeps you feeling fuller for longer. So it increases the likelihood of you actually being able to stick to the calorie deficit long term too.

As an energy source, protein does contribute about 4 calories for every gram consumed, although this is just an average and it doesn’t fully account for the TEF. But for all practical purposes, we say that protein has 4 calories per gram.

Most people need a lot more protein than they’re likely eating currently. This is the area people usually struggle with most when implementing dietary changes, but more on this later. The question now is, how much protein do we need?

How Much Protein Should You Eat

There is a lot of confusion about how much protein you should eat. But there is actually a relatively clear answer to this question. However, unfortunately, many organisations are still using out dated information in their recommendations, which does make it harder to know who to trust on this.

You see, in most countries, the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. However, what most people take this to mean is that this is the amount you should eat. But this is not correct.

The RDA is the minimum amount you need to consume to prevent deficiency. This is not the optimal amount, it is the amount that you absolutely do not want to eat less than. It is also based on outdated methods of estimating protein requirements, and the actual minimum amount to prevent deficiency is actually higher when using more up to date methods (such as Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO)).

If you are eating less than this amount of protein, you are eating a deficient diet and you are malnourished. This may come as a shock to many people, but it is the reality of the situation. Having coached a lot of people, I know that quite a lot of people aren’t even consuming this bare minimum amount of protein.

So how much protein should you be consuming then?

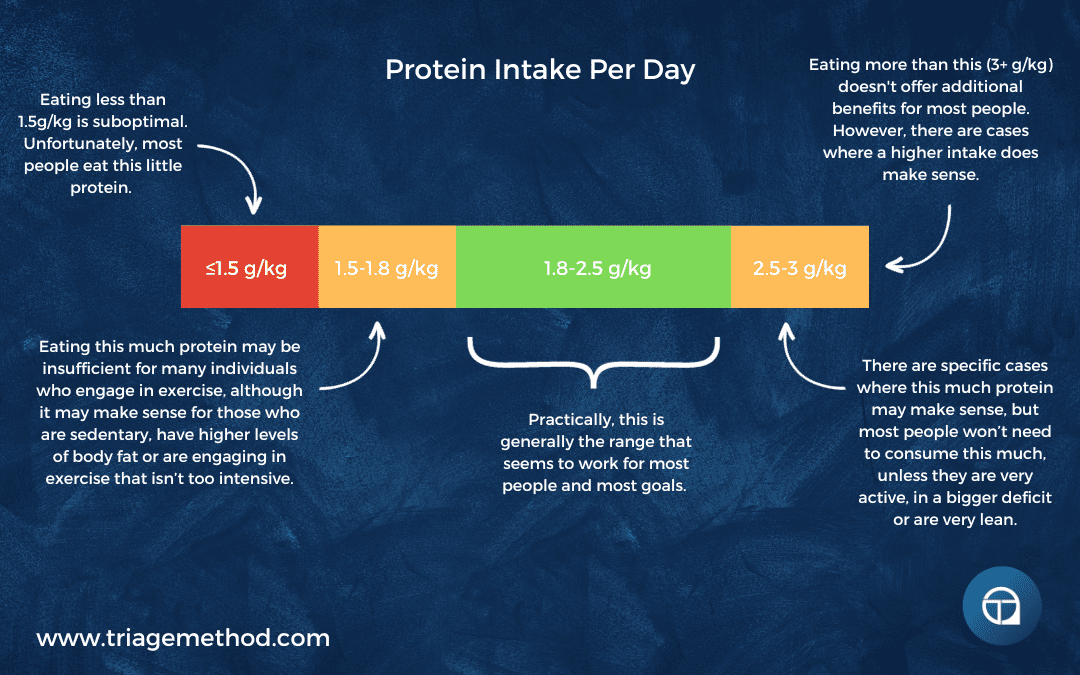

Using the most up to date research, a very rough and ready rule of 1.5-2.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight is what we generally recommend (although there are some cases and populations where higher intakes are needed, so this should be seen as a very rough starting point). There’s not a huge benefit from going beyond the higher end (outside of specific cases), and going below 1.5 isn’t generally sufficient for people who exercise (although if you are sedentary, you can probably get away with intakes as low as 0.93-1.2g/kg/day, although this may still not be optimal).

We like somewhere around 1.8-2.2 grams per kilogram for the vast majority of people, and I very often just say 2g/kg/day to make things easier to remember. Narrowing the range ensures that you do actually get enough protein each day, as some people may still be eating suboptimal amounts of protein at 1.5g/kg/day and some people will simply not need to consume 2.5g/kg/day. However, the vast majority of people who exercise will fall within the range of 1.8-2.5g/kg/day. So this is probably where you should set your target intake.

Ideally, we would set this target based on your lean mass, as body fat doesn’t contribute massively to protein intake requirements, however, getting an accurate lean mass figure isn’t really all that easy or practical (although you can use our body fat and lean mass calculators to get an estimate of your body composition). So you will simply have to use figures that work for your body weight, rather than lean mass, but we can still take it into account.

To set your protein target, you simply take your body weight in kilograms and multiply it by 1.8 to 2.2, and this will be your protein intake in grams. If your body fat is quite high, I would stick to the lower end of the range (1.8-2), whereas if you are already quite lean, it may be prudent to stick to the higher end of the range (2.2 or even higher).

If you have a lot of body fat to lose and are quite a bit above a healthy weight for you, especially for women, a protein intake of closer to 1.5g per kilogram may even be more appropriate, although higher protein intakes may still be beneficial in this case, due to the fact that higher protein intakes are quite satiating (hence why we still generally suggest 1.8g/kg/day as the lower end).

For example, if you are 70kg, your protein intake will fall in the range of 126-154 grams per day.

If your maintenance calories were 2000, and we set our protein target as 126g, this would leave 1496 calories for carbohydrates and fats (remember, every gram of protein is 4 calories, so 126 multiplied by 4 equals 504, and we then subtract that from 2000 to get the remaining calories).

If you want the simple answer to “how much protein should I eat?”, then we generally recommend that you aim to consume 1.8-2.2g per kg of protein per day, spread out across the day, relatively evenly.

Now, I know that some of you may be thinking that this is way too high and couldn’t possibly be the target. You may even have heard that eating too much protein is bad for you. So this does bear addressing this.

Can You Eat Too Much Protein?

There are many suggested reasons put forth as to why you shouldn’t eat a high-protein diet. But these claims mostly fall flat when you actually look at the evidence. Let’s go through these claims and see if we can clear things up:

Kidney Strain: One of the most commonly discussed concerns with high protein intake is the potential strain it places on the kidneys. The kidneys filter waste products from protein metabolism, and consuming large amounts of protein can increase their workload. In healthy individuals, this isn’t an issue. While very high-protein diets have been linked to potential kidney strain in people with pre-existing kidney issues, for healthy individuals, excess protein is generally not harmful. Excess protein is either excreted or converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis, so it’s important not to drastically overconsume protein at the expense of other nutrients like carbohydrates and fats (as it will just be converted to carbohydrates). However, it is important to note that for people with pre-existing kidney conditions, excessive protein can exacerbate kidney damage or contribute to a faster decline in kidney function.

Digestive Issues: A diet too high in protein can lead to digestive discomfort, such as constipation or bloating, particularly if it comes at the expense of fibre-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Protein-heavy diets are often low in fibre, which is essential for healthy digestion and preventing constipation. This isn’t actually an issue of eating too much protein, rather it is an issue of eating more protein at the expense of other vital components of the diet (i.e. fibre). This is easily overcome by simply eating a well balanced diet (which you will learn how to do by the end of this article series).

Liver Health: In individuals with pre-existing liver conditions, excessive protein consumption can overburden the liver. The liver is responsible for processing protein, and consuming it in large quantities can cause an increased production of toxic byproducts like ammonia, which may exacerbate liver dysfunction. This is not really an issue for healthy individuals.

Increased Cancer Risk: Some studies suggest that high consumption of processed meats, often part of a high-protein diet, may be associated with a higher risk of certain cancers, such as colorectal cancer. This risk is thought to be linked to the processing methods, preservatives, and cooking techniques, rather than protein itself. Plant-based protein sources and lean meat sources are considered healthier alternatives in this context, and don’t seem to have this issue. Eating processed meats generally isn’t ideal from a health perspective.

Increased Osteoporosis Risk: I don’t know where this myth began, but many people believe that eating a lot of protein increases the acid load on the body, leading to calcium loss from bones. However, long-term studies have shown that high-protein diets do not cause osteoporosis. In fact, adequate protein intake is essential for maintaining bone health, especially in older adults.

Increased Risk of Heart Disease: High-protein diets, especially those rich in red or processed meats, can be linked to increased cholesterol levels and a higher risk of heart disease. This is less to do with the actual protein component, but rather the fact that some animal-based proteins are high in saturated fat, which contributes to plaque buildup in the arteries, increasing the risk of cardiovascular issues. We generally recommend individuals eat leaner sources of protein and manage their saturated fat intake, which leads this to be a non-issue.

Impact on Longevity: While protein is essential for growth and repair, excessively high-protein diets, particularly those centred around animal sources, have been linked to reduced longevity in some studies. Excessive consumption of animal proteins might excessively activate certain pathways like MTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin), which is associated with ageing and an increased risk of diseases like cancer. However, when studies are done in humans and controlled for stuff like processed meat consumption, this seems to not be an issue. It is not necessarily the protein that is responsible for issues, but rather the overall dietary pattern of individuals who eat more protein (generally eating a diet higher in processed meat and foods).

Ultimately, there may be some extra ageing stimulus from the MTOR stimulation, but this is also likely to result in the individual having more muscle mass (MTOR signals the body to build muscle), and we know having more muscle is one of the best protections against premature death and is associated with a much higher quality of life. So I would not be worried about this aspect of things, assuming you eat a generally high quality diet and aren’t relying on processed meats to reach your protein target, and are instead, getting your protein from a mix of lean, unprocessed meats and plant protein sources.

So, a lot of the issues that people bring up with regard to the risks of excess protein intake don’t really hold up to scrutiny. Diets of more than 4.4g of protein per kg of body weight have been studied, and in otherwise healthy populations (i.e. no underlying kidney issues) no harm has been seen. These naturally aren’t “whole life” studies, as it would be astronomically expensive and impractical to do a whole life nutrition study in humans. So we don’t have answers to some of the questions we have around this topic, especially in relation to impacts on longevity.

But, the consensus seems to be that in otherwise healthy individuals, you can’t really eat too much protein. You can certainly overconsume calories by way of protein, but this is far less likely than carbs or fats. You can also eat so much protein that it displaces other components of the diet, and as a result, eat a diet that is less healthy overall. But as protein is very satiating, it is actually quite hard to actually overconsume, and in general, most people are unlikely to eat too much protein.

Most people don’t need to eat an excessively high protein diet (>2.5g/kg/day), but you definitely want to ensure you don’t eat a low protein diet either (<0.93-1.2g/kg/day if you are a sedentary individual, and <1.5g/kg/day if you do any kind of exercise).

What Happens If You Eat Too Little Protein?

While a lot of attention is paid to sensationalist claims about the dangers of eating too much protein, too little attention is paid to the dangers of eating too little protein. We very frequently see people in our coaching practice who are eating very little protein, and as a result are experiencing many of the symptoms and effects of a low protein diet.

Increased Hunger and Poor Dietary Adherence: Protein has a high satiety factor, meaning it helps keep you feeling fuller for longer. If you’re not getting enough protein, you may experience increased hunger, which generally leads to overeating and cravings for less nutritious, high-calorie foods. This can result in weight gain and poor adherence to a balanced diet. This is one of the things we work on a lot with our clients at the start of the coaching process, and it really does have outsized returns.

Muscle Loss or Poor Muscle Growth: Protein is crucial for maintaining muscle mass. A lack of adequate protein can lead to muscle wasting, as the body starts breaking down muscle tissue so it can access essential amino acids. This can result in decreased strength, poor physical performance, and an increased risk of injury, especially in older adults. Individuals at the borderline of insufficient protein may experience poor muscle growth. We have a lot of clients come to us who want to build muscle, and who simply aren’t eating enough protein. Once they start eating sufficient protein, muscle gain is much easier and quicker.

Poor Physical Performance: Since muscle mass and function rely on a steady intake of protein, insufficient levels can lead to a decline in physical endurance and strength. Tasks that were once easy may become increasingly difficult as muscles weaken and recover more slowly from activity. This is particularly evident in the elderly, but it actually also happens to most individuals once they are beyond adolescence and no longer have an abundance of circulating anabolic hormones. This is why you see many people steadily losing muscle and function from their early 20s onwards. This isn’t hugely evident at first, but by around the late 20s and early 30s, most individuals have actually lost significant muscle and strength.

Low Energy Levels: Protein plays a key role in maintaining blood sugar balance and supporting the body’s metabolic processes. Inadequate protein can result in feeling fatigued or lethargic, as the body struggles to regulate energy efficiently. This lack of energy can impact everything from daily activities to cognitive function. Recovery from the general wear and tear of everyday life takes longer when protein intake is low, and many individuals just experience this sense of “poor recovery” and generalised fatigue when protein intake is low.

Impaired Immune Function: Protein is essential for producing antibodies, which help defend the body against infections. Insufficient protein intake can weaken the immune system, making you more susceptible to illnesses, infections, and slower recovery times when you do get sick.

Slower Healing and Recovery: Protein is necessary for tissue repair. Without enough, your body’s ability to recover from injuries, surgeries, or even general physical activity will be compromised, prolonging recovery times and potentially increasing the risk of complications.

Impact on Appearance: Hair, skin, and nails are made primarily of a protein called keratin. When protein intake is inadequate, the body prioritises essential functions, leaving non-essential areas like hair and skin under-resourced. This can result in thinning hair, brittle nails, and dry, flaky skin. Over time, the skin may lose elasticity, and wounds may take longer to heal due to impaired collagen production.

Mood and Cognitive Function: Amino acids from proteins are needed for the production of neurotransmitters, which regulate mood and cognitive function. A deficiency can lead to mood disturbances like irritability, anxiety, and even depression. It can also impair focus, memory, and mental clarity.

Bone Health: Protein is vital for maintaining strong bones. A deficiency can lead to lower bone density, increasing the risk of fractures and osteoporosis, especially in ageing populations. This happens because protein helps with calcium absorption and the maintenance of bone structure.

Oedema (Fluid Retention): Protein helps maintain a proper balance of fluids in the body by keeping water in the bloodstream. A lack of protein can lead to a condition called oedema, where fluid accumulates in tissues, causing swelling, particularly in the feet, legs, and hands. This generally isn’t a concern for most people, but it is important to note that protein plays a role in the proper fluid balance of the body.

Reduced Longevity and Healthspan: Long-term protein deficiency can lead to frailty and sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss), significantly reducing both lifespan and healthspan. A lack of protein contributes to a decline in overall health, increases the risk of chronic diseases, and accelerates the ageing process (via accelerated sarcopenia).

Ultimately, if protein intake is low for long enough, you do end up just having lower healthspan and lifespan. This should be obvious enough, as eating a low protein diet is a form of malnutrition, and unfortunately, the effects of this do just take a while to manifest. It is also very unfortunate that a lot of people are unaware of just how much protein they need to consume to actually eat sufficient amounts.

You want to consume at the very least 0.93-1.2g/kg/day if you are a sedentary individual and 1.5g/kg/day if you do any kind of exercise.

The minimum target may actually be higher for you as an individual, as these are just general numbers. We can actually tailor your targets more specifically for you and your needs, as there are a number of factors that influence protein needs.

Factors That Influence Protein Needs

There are a number of factors that influence your protein needs, and understanding these will allow you to tailor your protein target more specifically for your unique needs.

Protein Quality

The first factor that influences protein needs is actually protein quality. Remember, we have amino acid needs, not protein needs. So naturally, you are going to need to eat less of protein sources that actually allow you to get all of the amino acids you need in sufficient quantities versus protein sources that don’t contain all the amino acids you need or don’t have them in sufficient quantities.

You can imagine a scenario where you are able to get all your amino acid needs from a relatively small amount of protein. You can also imagine a situation whereby you eat an enormous quantity of protein, yet still don’t actually reach your amino acid needs.

So protein quality does influence your protein requirements. While we briefly touched on protein quality already, I think expanding on this will really help you to better understand how much protein you should eat.

Protein quality is a bit of a confusing term, so it does help to elaborate on this a little bit. A higher quality protein is one that provides you with all of the amino acids you need, especially the essential amino acids (which you must get from the diet) and is actually easily digested and absorbed by the body (we don’t just care about the amino acids that can be measured in a protein source in the lab, we care about actually getting them into the body). In general, this means we want to focus on mainly consuming “complete proteins” that have a high “bioavailability”.

Complete Proteins: These proteins contain all nine essential amino acids, which are the amino acids that the body cannot synthesise and must obtain through diet. Animal-based protein sources are typically complete proteins, including meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products like milk, yoghurt, and cheese. Some plant-based options, such as quinoa, soy, hemp seeds, and buckwheat, also provide a complete amino acid profile, making them valuable protein sources for plant-based eaters.

Incomplete Proteins: Most plant-based proteins fall into this category, meaning they lack one or more of the nine essential amino acids. Common incomplete protein sources include beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, and grains. While these foods do still have protein, you would need to combine different plant-based foods to form a complete protein. For example, combining rice (which lacks lysine) with beans (which are low in methionine) creates a complete amino acid profile, providing all essential amino acids.

Bioavailability: Bioavailability refers to how well the body absorbs and uses the protein from food sources. Animal-based proteins tend to have higher bioavailability compared to plant-based proteins due to their more balanced amino acid profiles and greater digestibility. For example, proteins from eggs, dairy, and meat are more easily absorbed and utilised by the body compared to many plant proteins. Among animal sources, whey protein stands out with one of the highest absorption rates, making it very popular in muscle building circles.

Plant proteins, while nutritious, often have lower bioavailability due to fibre content, antinutrients (e.g., phytates and tannins), and incomplete amino acid profiles. However, processing methods such as fermentation, sprouting, or cooking can improve the digestibility of plant proteins.

You can also eat a mixed diet of animal and plant based proteins, with a mix of complete and incomplete proteins. It doesn’t have to be one or the other, as we are looking at overall protein intake and amino acid profile, not just individual proteins.

There are a number of protein scoring systems that aim to help you identify higher quality protein sources. I wouldn’t use these as absolutely perfect systems, as there are numerous issues with them, but they are helpful for understanding the concept of better and worse protein sources.

The two systems we generally discuss in relation to this are the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) and Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). As I discussed DIAAS in our nutrition course, I will just discuss PDCAAS here.

The PDCAAS is a system that measures protein quality by considering both the amino acid composition of a food and its digestibility. The score ranges from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating a higher quality protein source. A PDCAAS score of 1 means the protein provides all essential amino acids in the proper amounts for human nutrition and is highly digestible.

Here’s how common protein sources compare based on PDCAAS:

- Whey Protein: Whey, derived from milk, has a PDCAAS of 1.0, making it one of the highest-quality protein sources. It’s quickly absorbed and rich in branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), particularly leucine, which plays a critical role in muscle protein synthesis.

- Casein: Also sourced from milk, casein has a PDCAAS of 1.0. Unlike whey, it digests slowly, providing a more sustained release of amino acids, which is often touted as beneficial for muscle maintenance over longer periods (e.g., overnight).

- Soy Protein: Soy is one of the highest quality plant-based proteins, with a PDCAAS of 1.0, matching that of animal proteins. It contains all essential amino acids and is a popular option for vegetarians and vegans.

- Egg Protein: Egg whites have a PDCAAS of 1.0 and are considered a gold standard for protein quality. They are highly digestible and provide all essential amino acids.

- Beef: Beef has a PDCAAS score of 0.92, which still makes it a high-quality protein source, but slightly lower due to its digestibility compared to dairy and egg proteins.

- Lentils and Beans: These plant-based sources have PDCAAS scores ranging between 0.5 to 0.7. While rich in nutrients and fibre, they are incomplete proteins and less digestible than animal sources.

- Wheat Protein (Gluten): Wheat protein, found in foods like bread and pasta, has a PDCAAS of around 0.4, making it one of the lower-quality protein sources. It lacks sufficient lysine and is less digestible compared to other sources.

Now, you don’t need to be excessively worried about optimising your amino acid profile, as simply eating a diet of mixed protein sources, in sufficient quantities will lead to a good amino acid profile. However, I am bringing this to your attention as something that influences how much protein you need to consume because there are cases where you will want to pay more attention to your protein quality and amino acid intake, and may need to adjust your protein target as a result.

Certain amino acids, particularly leucine, play a critical role in stimulating muscle protein synthesis. Leucine is one of the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) that directly influence the body’s ability to repair and build muscle tissue. Foods rich in leucine, such as whey protein, chicken, eggs, and dairy, are highly beneficial for muscle growth and recovery. Research suggests that consuming adequate leucine, especially after exercise, can optimise muscle repair and promote muscle hypertrophy.

So if you are someone who is interested in optimising muscle building, you are going to want to ensure that you eat sufficient leucine throughout the day. This generally isn’t too much of an issue if you are eating animal proteins, but it can be an issue if you are predominantly plant based.

Similarly, many plant based proteins are incomplete proteins, which means that even if you are hitting the general protein recommendations, you may actually still be deficient in proteins. This can sometimes be overcome by simply eating more protein (despite what you often hear, plant based dieters may actually need more protein, not less). Sometimes eating more protein simply isn’t going to overcome an insufficient amino acid intake, especially if it is the essential amino acids that are deficient.

However, while many plant-based proteins are incomplete, it is entirely possible to get all essential amino acids through a well-planned plant-based diet. Combining different plant protein sources throughout the day, such as pairing rice and beans, can provide all nine essential amino acids. Additionally, certain plant foods like quinoa, soy, hemp seeds, and chia seeds are complete proteins by themselves, making them particularly valuable for vegans and vegetarians seeking diverse protein sources. But you may just need to eat these foods in unrealistic quantities to actually hit your amino acid needs, and this is where something like a soy protein powder may be helpful as it is a complete protein that is relatively high in the essential amino acids.

Ultimately, depending on your exact situation, you can tweak the protein targets to make it more likely that you will actually cover all your amino acid needs. This generally doesn’t need to be micromanaged if you are eating a mixed diet, but may need more attention if you are eating a plant based diet.

Beyond protein quality, there are some other factors that influence your protein needs.

Age and Protein Needs

Protein requirements vary a little bit throughout the different stages of life. I know most of you reading this are likely adults, so may not be as interested in the protein needs of children or teens, but you will all hopefully grow old one day, so it is important to understand that protein needs do potentially change as you age. Ensuring appropriate protein intake during each phase is essential for optimal growth, maintenance, and overall health.

Protein Needs for Children (4 to 12)

Children require sufficient protein to support rapid growth and development, particularly for height, muscle development, and tissue repair. During early childhood, protein intake supports the development of the brain, organs, and immune system. Protein needs for children are likely around 1.3 to 1.55 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. This is further increased if they are more active and engaged in sports. Adequate protein intake is required to aid in the development of lean muscle mass, bone strength, and height.

Protein Needs for Teens (12 to 18)

During adolescence, especially around puberty, protein is crucial for supporting not only growth in height but also the development of muscle mass, bone density, and overall sexual maturation. Teenagers experience rapid physical changes, and protein needs are often higher during this time to accommodate muscle synthesis and overall development. Teens typically require 1 to 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, though athletes and highly active teens may need more. Adequate protein intake during these formative years can help lay the foundation for lifelong health. Teens likely don’t actually need as much protein as adults, because they have such high circulating anabolic hormones, and lower levels of muscle mass compared to adults. Although there is no reason for them to necessarily avoid consuming higher amounts of protein, especially if they are quite active and/or actively want to build more muscle.

Protein Needs for Adults (19 to 64)

For most adults, protein is essential for maintaining muscle mass, repairing tissues, and supporting the body’s metabolic functions. We generally recommend that adults aim for 1.5-2.5g per kg of protein per day.

Protein Needs for Older Adults (65+)

As people age, muscle mass naturally begins to decline, a condition known as sarcopenia. To combat muscle loss and maintain strength, older adults need higher protein intake than their younger counterparts. We generally suggest that older adults should aim for 1.5-2.5g per kg of protein per day. While younger individuals can get away with less than 1.5g/kg/per day if they are sedentary, older adults may still need a high amount of protein even if they are sedentary. Higher protein intake is needed to preserve lean muscle mass and strength, and older adults tend to become somewhat resistant to the anabolic signalling that protein provides.

Summary of Protein Needs by Age Group:

- Children (4-12 years): 1.3 to 1.55 grams per kilogram of body weight.

- Teens (13-18 years): 1 to 1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight (higher for athletes or active teens).

- Adults (19-64 years): 1.5 to 2.5 grams per kilogram of body weight.

- Older Adults (65+ years): 1.5 to 2.5 grams per kilogram of body weight.

Ensuring adequate protein intake at every stage of life helps support growth, muscle maintenance, and overall health, especially during periods of heightened growth or ageing-related muscle loss.

In general, somewhere around ~1.5g/kg/day seems to work well for most individuals across their lifespan, however, depending on your specific situation, you may need to adjust this. If you are struggling to maintain muscle as you age, you may need slightly more protein than that. If you are easily maintaining muscle and performance, then you may not need that much.

Body Composition and Protein Intake

Protein requirements are often discussed in terms of total body weight, but a more accurate method would be to base protein targets on lean muscle mass rather than total body weight. This is because lean mass (fat-free mass, including muscles, organs, bones, and connective tissues) has a higher metabolic demand for protein compared to body fat.

Lean mass, unlike fat, is metabolically active and requires a steady supply of amino acids for maintenance, repair, and growth. Since muscle protein synthesis relies heavily on adequate protein intake, individuals with higher lean mass generally have greater protein needs than individuals who weigh the same but have higher body fat.

Two people with the same total body weight but with different body compositions (one with higher muscle mass and one with higher fat mass) will have different protein needs. The person with more muscle mass will require more protein to support muscle maintenance and repair, while the person with more body fat will require less protein because fat tissue does not have significant protein or amino acid needs.

So setting protein targets based on fat free mass rather than total body weight would be ideal because it more accurately reflects the body’s true need for protein. Body fat is not as metabolically active as muscle and has little demand for amino acids. Therefore, calculating protein intake based solely on total body weight can lead to either over- or under-estimating needs, especially in individuals with higher body fat percentages.

For instance, an overweight individual calculating protein needs based on total body weight might consume more protein than they actually require. Conversely, a lean individual with a low body fat percentage and a high muscle mass might not be consuming enough protein if they base their intake on total weight instead of lean muscle mass.

While you can calculate your protein requirements based on your fat free mass, we generally don’t tend to do this. While setting protein targets based on lean mass is ideal, it presents practical challenges. Most people don’t have easy access to tools to measure body fat accurately (although you could use our body fat calculator).

For this reason, in our coaching practice we use total body weight as a proxy, but, we then just adjust the protein target based on body composition. This is especially true if someone is very outside of the average (either very low body fat or very high body fat).

For individuals with higher body fat, we will generally stick to the lower end of the protein target per kilogram of total weight, while for those who are leaner, we may stick to the higher end of the protein intake range.

Ultimately, while setting protein targets based on fat free mass is a more precise, it is also quite impractical and we can just use the much easier to measure body weight instead. But we can still take account of the fact that if you have more body fat, you may not need to set your protein target towards the higher end of the range. There may still be benefits to eating a higher protein intake, especially with regard to satiety, but in general, if you have more body fat, you can just use the lower end of the protein target range.

Sex and Protein Intake

Sex also plays a role in determining optimal protein intake. However, this has less to do with hormonal differences or inherent sex based metabolic differences, and more to do with the differences in fat-free mass (mostly muscle mass). Of course, a large portion of the difference in fat free mass between men and women is due to differences in hormones and genetics, but these differences don’t necessarily impact protein recommendations, outside of the fact they cause differences in lean mass.

We do discuss the difference in fat free mass between the sexes in the article that accompanies our fat free mass index calculator. If you want to read up more about this topic.

For the most part, the difference in protein needs between men and women is related to the fact that, on average, men tend to have more muscle mass and less body fat than women. Since muscle tissue is metabolically active and requires more protein for maintenance, repair, and growth, men typically have slightly higher protein needs compared to women of the same weight.

Men tend to require around 1.5-2.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. However, women generally can get away with slightly lower targets of 1.5-2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. However, active women, athletes, women engaged in resistance training, and women who have relatively low body fat may have protein needs comparable to or even exceeding those of men. When we set protein targets for our clients, we do take sex into account, but we are generally more influenced by the individual’s body composition rather than their sex.

However, as women do potentially experience life stages that men don’t, such as pregnancy and lactation, there may be slight differences in protein requirements between men and women at these different stages of life.

During pregnancy and lactation, a woman’s body undergoes significant changes that increase protein requirements. Protein is essential for the growth of the fetus, the development of maternal tissues such as the placenta, and for maintaining maternal muscle mass. Additionally, during lactation, protein is needed to produce nutrient-rich breast milk for the baby’s growth and development.

Pregnant women typically require around 1.22 to 1.52 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day (and potentially more if they are also engaged in exercise). These needs increase gradually throughout pregnancy, with the third trimester being particularly important due to rapid fetal growth. Protein supports not only fetal tissue development but also the expansion of maternal tissues like the uterus, blood volume, and breast tissue. These numbers would obviously be higher if you continue to engage in exercise while pregnant, and if you are leaner at the start of pregnancy.

Breastfeeding women also need more protein to support milk production and recovery from pregnancy. This translates to an intake of about 1.5 to 2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, similar to or even higher than during pregnancy. Protein is crucial for the production of high-quality breast milk that provides the necessary amino acids for the growing infant.

Of course, women also go through menopause and men don’t. However, this doesn’t really change the protein recommendations. Menopausal women may want to increase protein intake during this time, as they have a reduction in hormones that reduce muscle breakdown and may need slightly more protein as a result, however, this isn’t perfectly clear.

Overall, there are slight differences in protein intake between men and women, especially during specific points across the life cycle. But the differences aren’t massive and in most cases, consuming at least 1.5g/kg/day of protein will cover most cases, which is the low end of our general recommendation anyway. How much protein you should eat can be modified by your exact situation, and thus you need to tailor your protein intake based on your exact situation.

Activity Type and Level, and Protein Intake

Your protein needs vary significantly based on the type of activity you engage in, and of course the level of intensity of that activity. Active individuals generally require more protein to support muscle repair, growth, and overall performance compared to sedentary individuals.

Sedentary individuals have lower protein requirements since their body’s need for muscle repair and maintenance isn’t as high. The protein intake target for sedentary individuals is between 0.93-1.2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. At this level, protein primarily supports basic physiological functions like tissue repair and hormone production.

So, even if you are mostly sedentary, it is important to meet these minimum protein needs to prevent muscle loss and support overall health. For those who are completely inactive, consuming 0.93 grams per kilogram of body weight daily is generally sufficient, but we generally recommend even sedentary individuals to aim for the higher end of the range (1.2 grams per kilogram) to ensure they are eating enough protein, particularly as they age. Eating slightly more protein than you may need in this context, usually results in a better overall diet and generally leads to much higher levels of satiety.

Active individuals require more protein to meet the demands of increased physical activity. At the very least, we recommend that active individuals should aim to consume 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily.

If you are more intensely active, perhaps consider yourself an athlete, and engage in intense physical activity, then your protein requirements are likely higher. The amount of protein required does vary depending on the type of exercise being performed, with endurance and resistance training placing different demands on the body.

Resistance-Trained Athletes: Those involved in resistance training, require protein to repair and grow muscle tissues that are broken down during workouts. The recommended intake for resistance-trained athletes is at least 1.49-2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. This level of protein supports muscle hypertrophy (growth) and repair after intense strength sessions. However, more may actually be needed, especially if you are really pushing training. These figures are just the minimum amount required for these populations, and there may be benefits to going beyond this amount. You also don’t know if you personally are someone who only needs ~1.5g/kg/day or if you are someone who needs much more than this. So generally, we recommend resistance training individuals consume 1.8-2.2g/kg/day, but some of you may actually need more than this.

Endurance Athletes: Interestingly, endurance athletes, such as runners, cyclists, and swimmers, often require slightly more protein than resistance-trained athletes. Endurance athletes should aim for 1.65-2.1 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. This is because, during prolonged endurance activities, amino acids can be used as an additional energy source when glycogen stores run low. Additionally, endurance training still involves muscle damage that requires repair, and many of the cellular structures that enhance endurance performance, such as mitochondria and other cellular proteins, are made from amino acids. Endurance athletes also tend to be leaner and have lower body fat percentages, which means the protein target being set by weight isn’t as impacted by body fat levels and is closer to being set based on fat free mass. Endurance exercise also promotes the breakdown of some muscle proteins as the body seeks amino acids to fuel extended activities, making protein intake critical for recovery. Unfortunately, very often, endurance athletes under-consume protein and thus don’t maximise their performance as a result.

So, as you can see, your activity levels and the intensity of those activity levels does impact the protein recommendations. This is why we generally have quite a broad range of 1.5-2.5g/kg/day of protein. Most people who exercise will be covered by eating 1.8-2.2g/kg/day of protein, although some may need slightly more than this.

Calories, Macros, Dietary Goals and Protein Goals

How you set up the rest of your diet in terms of calories and macros does impact your protein targets. So too do your overall “dietary goals” (e.g. are you trying to lose weight, gain weight, maintain weight, improve body composition, improve health, improve performance etc.).

Calorie intake is probably one of the more significant modifiers of your protein target. When calories are restricted (such as during weight loss), protein needs typically increase to preserve lean muscle mass and promote fat loss. A deficit of calories creates a more catabolic environment, and more protein (an anabolic signal) may be needed to offset this breakdown.

On the other hand, during periods of calorie surplus (like when trying to gain muscle), you may not need as much protein because the extra calories, especially from carbohydrates, create a more anabolic environment that supports muscle growth.

It is probably easiest to discuss this more fully by referencing back to the three main ways in which you can set up your calories; a calorie deficit, calorie maintenance and a calorie surplus. These generally correspond to weight loss, body weight maintenance (or body recomposition) and weight gain. So we will discuss how these different phases affect your protein targets.

Weight Loss

When you are losing weight, you are often in a calorie deficit, meaning your body will be burning more calories than you consume. In this state, there is an increased risk of losing muscle mass along with fat. Consuming adequate protein during a calorie deficit helps to prevent muscle loss (and may even result in some muscle gain), and because protein is so satiating, consuming sufficient protein during this phase generally leads to increased adherence to the deficit (and thus generally better results).

Protein does also has a higher “thermic effect of feeding” (TEF) than carbohydrates and fats, meaning your body burns more calories digesting and processing protein, thus potentially further supporting weight loss efforts.

Generally, we recommend higher protein intake during weight loss, and we usually suggest around 1.8 to 2.5 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. This increased protein helps offset the catabolic effects of calorie restriction and preserves muscle mass while promoting fat loss.

If the calorie reduction is quite aggressive, and/or if a large portion of the deficit is coming from reductions in carbohydrates, protein needs may need to be on the higher end of the range (closer to 2.5g/kg/day of protein). This is due to the fact that carbohydrates provide an anti-catabolic effect, which spares muscle tissue, and more aggressive diets are inherently more catabolic.

Weight Gain

When aiming to gain muscle, the primary focus is on consuming a calorie surplus, as more energy is required to support muscle growth and to fuel the performance in the gym which leads to more muscle being built. While protein is still important for muscle building, you don’t need to go overboard with protein consumption. The extra calories, especially from carbohydrates, create an anabolic environment that promotes muscle growth by stimulating insulin release, which helps shuttle nutrients into muscle cells. With this extra anabolism from the surplus of calories and carbohydrates, your protein needs may actually be lower than when you are trying to lose weight.

While this is a discussion of how much protein you should eat, we do have to just touch on carbohydrates. Carbohydrates play a key role in creating a high anabolic environment. They replenish glycogen stores and fuel intense workouts, allowing the body to focus on muscle repair and growth. As a result, the need for excessively high protein intake is diminished, as the extra calories (primarily from carbs) support muscle growth.

For those in a muscle-building phase, 1.5-2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day is sufficient. The higher end of the range is recommended for those with high training volumes or during periods of more intense strength training. However, because you’re in a calorie surplus, the body will be more efficient at building muscle, even if protein intake is on the lower end. Eating protein on the higher end of the range may still offer benefits, however, as protein is so satiating, eating too much protein may just lead to excess fullness and thus an inability to eat the calories that are needed to gain muscle.

It is important to note that it is possible to gain muscle on a lower-protein diet if total calorie intake is sufficient and strength training is part of the routine. However, the muscle-building process will be less efficient without adequate protein. This is because protein provides the building blocks necessary for muscle tissue repair and synthesis. A lower-protein diet can still support muscle growth, but gains will likely be slower. So we do still generally recommend individuals consume at least 1.8g/kg/day of protein when dieting.

Weight Maintenance

If you are aiming to maintain your weight, you can follow a more moderate approach to protein intake. At this stage, you are not in a calorie deficit that risks muscle loss, nor are you in a calorie surplus aimed at really pushing muscle gain. However, adequate protein intake is still important for maintaining muscle mass, supporting recovery from exercise, and promoting overall health.

For maintenance, 1.5-2.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day is our recommended range. Some people may choose to eat at the lower end, while others will choose to eat at the higher end. It really depends on what you are ultimately looking to achieve.

Some people eat at maintenance to support their health, while others eat at maintenance to support performance. Others again will be eating at maintenance to try and get some sort of body recomposition effect, where they lose some fat and gain some muscle.

For individuals looking for body recomposition, protein plays a critical role. During body recomposition, you eat at maintenance (or maybe a very slight calorie deficit) combined with adequate protein intake and hard resistance training and cardio, and this can lead to some fat loss while preserving or even gaining muscle mass. But it is a very, very slow process.

Generally, to support body recomposition, a higher protein intake of 2-2.5 grams per kilogram of body weight per day is recommended. You are basically trying to force muscle gain to occur, and every little bit of extra anabolic stimulus helps. You may not actually need this high of a protein intake, but you have to train very hard to get a body recomposition effect and if you are going to lose fat while gaining muscle, you need to ensure that you have enough protein to stave off any muscle lose while also fuelling muscle gain.

Beyond weight loss, weight maintenance, or weight gain, different dietary goals such as supporting health or supporting performance do necessitate tweaking of the protein targets. However, these still generally fall within the 1.5-2.5g/kg/day of protein, and thus don’t necessitate us spending more time discussing them.

Injury, Illness, and Protein Intake

When you are ill or injured, your body’s protein requirements do actually increase significantly. Protein is essential for recovery, as it provides the building blocks needed for repairing damaged tissues, supporting the immune system, and preserving muscle mass. Ensuring an adequate protein intake during these times is crucial for faster healing and preventing further health complications.

Increased Protein Requirements During Injury or Surgery Recovery

When recovering from physical injury or surgery, the body requires extra protein to repair damaged tissues, regenerate cells, and support the healing process.

- Muscle Recovery: Injuries often involve damage to muscle tissues, whether from trauma, surgery, or immobilisation (e.g., a cast). Protein is vital for muscle repair and regeneration, helping to rebuild muscle fibres and reduce the risk of muscle atrophy.

- Bone Recovery: Protein also plays a significant role in bone repair, particularly when recovering from fractures or surgeries involving bone. Protein provides the necessary amino acids for collagen synthesis, which is a key component of bone structure.

- Organ Recovery: After surgery, particularly involving internal organs, protein is required to regenerate tissues and cells within the affected organs. For example, liver or kidney surgery will place extra demands on protein intake to ensure proper healing.

Protein intake should increase during recovery periods. For individuals recovering from injury or surgery, it is often recommended to consume 1.5–2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, depending on the severity of the injury and individual needs.

Protein and Recovery from Illness

Illness, especially conditions that involve inflammation or infection, places extra demands on the immune system. The immune system relies on amino acids, the building blocks of protein, to produce antibodies and other immune cells that fight off infections and promote recovery. Without sufficient protein, the immune system can weaken, slowing recovery from illness.

Protein is critical for synthesising immune system components, such as antibodies, cytokines, and enzymes that help defend against infections. When you are ill, the body breaks down more protein to fuel immune responses, which is why increasing protein intake is important to aid in recovery.

Just like injury, illness often raises protein requirements, especially for conditions that lead to inflammation or tissue breakdown, such as infections, chronic diseases, or trauma. Protein needs are around 1.5-2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day, depending on the severity and duration of the illness.

Preventing Muscle Loss During Bed Rest

Prolonged bed rest or immobility, whether due to illness, injury, or surgery, can lead to muscle atrophy (loss of muscle mass). This occurs because the muscles are not being used, leading the body to break down muscle tissue for energy and other needs.

Adequate protein intake can help minimise muscle loss during periods of bed rest. Protein provides the necessary amino acids to maintain muscle protein synthesis, even when physical activity is limited. Ensuring enough protein while immobilised or during recovery from illness can stave off the muscle-wasting effects of inactivity.

Individuals on bed rest due to injury or illness may need to consume at least 1.5-2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to preserve lean muscle mass and prevent excessive muscle loss.

When recovering from illness or injury, the body’s protein needs increase to support tissue repair, immune function, and muscle preservation. Whether healing from surgery, recovering from an illness, or experiencing prolonged bed rest, it is crucial to consume enough protein to speed up recovery and reduce the risk of muscle loss. A high-protein diet during these periods ensures that the body has the necessary resources to repair muscle, bone, and organs while maintaining immune health.

We can now turn our attention to protein distribution, as the way you spread out your protein intake across time is also important to understand.

Protein Distribution

Is there a best time to eat protein? This is a question that a lot of people wonder about, especially those interested in training performance and muscle building. Luckily, the answer isn’t too complicated, however, some people do find it hard to implement.

Ideally, we want to relatively evenly spread our protein intake out across the day. If we want to get really specific, for muscle building and general health, we ideally want to have 3-5 leucine-adequate protein feedings spread across the day. As we have discussed, leucine is an amino acid, and 3-5g is probably the adequate dose to signal muscle protein synthesis. To get this much leucine, you likely need ~20-30g of complete protein.

This will generally result in better muscle building/maintenance and performance, and it usually results in better dietary adherence overall. Protein is the most satiating macronutrient (i.e. it keeps you fuller for longer), and as such, it can actually make sticking to your diet a lot easier overall.

Ideally, you would consume some protein at every meal you eat, and beyond that, you don’t need to think about timing your protein intake too much. Now, one of the issues here is that people very often didn’t grow up consuming significant amounts of protein at the breakfast meal, and thus struggle in adulthood to get a more equal distribution of protein across the day. So it is important to come up with morning meal ideas that do contain protein because you won’t hit your protein target or ideally space your intake across the day by accident. We will discuss some protein sources in a moment, as I know from coaching many people that this can be difficult to implement.

The reason you want to generally eat protein spread throughout the day is because there is a refractory period for muscle protein synthesis. This means that once you stimulate it, it can’t be stimulated again for a number of hours. So if you want to maximise muscle building, you generally want to eat protein throughout the day.

Further to this is the fact that you can’t actually store protein. Unlike fat which can be stored as body fat, and carbohydrates which can be stored as glycogen, amino acids can’t be stored. Technically, they can be stored in the protein structures they build in the body, such as muscle. However, this doesn’t happen quickly. While there is some transient storage in the bloodstream, ultimately, once your immediate protein needs are met, excess protein is generally broken down, used for energy and/or excreted (or even potentially transformed into glucose (via gluconeogenesis) or even transformed to fats (via de novo lipogenesis)). This is why consistent protein intake is necessary.

You will hear that the body can only digest, absorb, and utilise ~30g of protein per meal. This would generally actually tend to line up well with our recommendation to eat a few protein meals spread throughout the day (4 meals of ~30g of protein is ~120g of protein per day, which is a decent daily protein intake for a lot of people), however, it is not actually true.

While ~30 grams of protein per meal is often recommended, the body will absorb and process protein beyond that. There is some transient storage of the amino acids, and you can eat more than this in one sitting and still utilise the vast majority of the protein. Of course, there likely is an upper limit to how much protein you can actually use from one sitting, but this is the same with any food component (i.e. you can eat more calories, carbs, fats or fibre than you can actually absorb and utilise in one sitting).

So your protein intake doesn’t have to be perfectly evenly distributed throughout the day, and there doesn’t need to be a cap of ~30g of protein per meal. It does make sense to relatively evenly distribute your protein intake across the whole day, but you don’t need to be excessively rigid about this, as long as you are actually eating sufficient protein.

While you will see quite a bit of hype about protein timing around workouts, a lot of this is actually rather overhyped. Once you are spreading your calories and protein out relatively evenly across the day, then protein timing around the workout becomes less important.

Yes, it certainly makes sense to supply the body with protein in either the before/during/after workout period, or some combination of all of them, but if you are following the rest of the guidelines outlined in this article and article series, you will naturally do that and don’t need to put a huge focus on this.

Eat a meal within the 1-3 hours before a workout, and another meal within the 1-3 hours after a workout and you are all good (assuming your meals contain protein, which they should). You certainly don’t need to be slamming a post-workout protein shake for your workout to be productive. That can certainly be a good strategy for some, but there is no magic to it.

If you can’t eat protein before your workout, then the post workout protein feeding does become more important. But even then, you really do just need to ensure you are eating sufficient protein relatively evenly spread across the whole day and you are good to go.

Some individuals who train multiple times per day may need to be a bit more diligent with their protein timing. However, even with these individuals, in general, simply spreading your protein intake out relatively evenly across the day is all they really need to focus on.

You will also hear people make a big deal over the pre-bed protein feeding. The rationale is that because you won’t be eating for 8+ hours while you sleep, you need to eat a slower-digesting protein like casein to ensure your muscles are well-fed with amino acids throughout the night.

However, the reality is that your body is well adapted to going hours between protein feedings. Once total protein is sufficient and you are generally spreading your intake out across the day, then you don’t need to excessively worry about optimally timing your protein intake before bed.

As a final point on this discussion about protein distribution and timing, we have to discuss total weekly protein versus daily protein goals. As you will remember from our previous article on calories, you can actually spread your calories out across the week in an uneven distribution. You don’t have to eat the same level of calories every day. Some days can be higher and some lower, as long as the total weekly calories add up to your target.

This is not quite the same for protein. Yes, your actual amino acid needs may vary day to day, depending on your activity level and what you do during that day. But because we can’t know our amino acid needs on a day to day basis, practically speaking, we are best off just eating the same amount of protein each day (even if calorie intake varies day to day).

Your body can’t significantly store protein, so you do need to eat it every day. You also can’t “make up” for missed anabolic opportunities where you didn’t stimulate muscle protein synthesis. So ideally, you want to hit your protein target every day.

Ultimately, how you distribute your protein intake does matter. However, you don’t have to be overly worried about this once you generally eat enough protein and consume it relatively evenly spread across the day.

Sources of Protein

We will discuss diet quality later in this article series, but I know that people very often struggle to increase their protein intake and need ideas for this.

We have a lot of clients, especially vegetarians, vegans, and people following certain restrictive diets patterns (e.g., low-calorie) often struggle to get enough protein. Plant-based proteins are less concentrated and sometimes incomplete, requiring more planning.

A lot of people also struggle with feeling like they have to eat the same foods every day to hit their protein target, and really struggle with a lack of variety in their diet, especially with regard to protein. This “diet fatigue” is a very frequent reason that people struggle to stick to a diet long term, and is something we very regularly have to work through in our coaching practice.

Having just discussed a lot about amino acids and stuff like complete and incomplete proteins, I know it can be a bit confusing and many people are left wondering what they should actually be eating to hit their protein target. A lot of people end up just over relying on protein shakes or the same ~2 protein sources to hit their protein target, and this does get boring fairly quickly.

So it is helpful to know what sources of protein are out there.

There are a wide variety of sources to choose from, including both animal-based and plant-based options. Each category has its own benefits, and understanding the differences between them can help you diversify your diet and ensure you’re getting the right balance of essential amino acids.

Animal-Based Protein Sources

Animal-based proteins are generally considered complete proteins, meaning they contain all nine essential amino acids that the body cannot produce on its own. These proteins tend to have high bioavailability, which means they are easily absorbed and utilized by the body. They are especially beneficial for individuals who need higher protein intakes, such as athletes, bodybuilders, and those looking to maintain or build muscle mass.

- Meat (Chicken, Beef, Turkey): Meat is one of the most popular and concentrated sources of protein. Lean meats like chicken breast and turkey are lower in fat, while beef offers more variety in fat content depending on the cut. All are rich sources of high-quality, complete protein that supports muscle growth and health.

- Fish (Salmon, Tuna): Fish, especially fatty fish like salmon and tuna, not only provide high-quality protein but also essential omega-3 fatty acids, which are beneficial for heart health. Fish is also easily digestible and can be a great option for those looking to diversify their protein intake.

- Eggs: Eggs are often regarded as a gold standard for protein due to their excellent bioavailability and complete amino acid profile. In addition to protein, they provide essential vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin B12 and choline, making them a nutrient-dense food.

- Dairy (Milk, Yoghurt, Cheese): Dairy products like yoghurt, cheese, and milk are excellent sources of complete protein. Greek yoghurt, in particular, is higher in protein than regular yoghurt and is a popular choice for breakfast or snacks. Cheese provides a concentrated source of protein and fat, but it should be eaten in moderation due to its higher calorie content.

- Protein Powders (Whey, Casein): Whey and casein protein powders are derived from milk and are convenient, highly digestible sources of protein. Whey protein is quickly absorbed, making it ideal for post-workout recovery, while casein is slowly digested, providing a steady release of amino acids, often consumed before bed.

Plant-Based Protein Sources

Plant-based proteins are often incomplete, meaning they lack one or more of the nine essential amino acids. However, they can be combined with other plant proteins to create a complete amino acid profile. Plant-based proteins also come with the added benefit of fibre, vitamins, and minerals, making them highly nutritious.

- Beans and Lentils: Beans (like black beans, kidney beans, and chickpeas) and lentils are affordable and versatile plant-based proteins. While they are incomplete proteins (typically low in the amino acid methionine), they are rich in fibre and essential nutrients like iron and folate. When combined with grains like rice, they form a complete protein.

- Tofu and Tempeh: Made from soybeans, tofu and tempeh are among the best plant-based protein sources. Soy is a complete protein, and contains all the essential amino acids. Tofu is more versatile and can be used in a variety of dishes, while tempeh has a firmer texture and contains more fibre due to the fermentation process.

- Soy Products (Edamame, Soy Milk): In addition to tofu and tempeh, other soy products like edamame (young soybeans) and soy milk provide high-quality, complete protein. Soy is an excellent option for those looking to avoid animal-based proteins while still getting all essential amino acids.

- Quinoa: Quinoa is one of the few plant-based foods that is a complete protein. It’s a pseudo-grain that is also rich in fibre, magnesium, and iron. Quinoa can be used in salads, as a side dish, or as a base for a plant-based meal.

- Chia Seeds and Hemp Seeds: These seeds are rich in both protein and healthy fats, particularly omega-3 fatty acids. While they are not considered complete proteins, they come very close and are packed with other essential nutrients like fibre and antioxidants.

- Plant-Based Protein Powders (Pea Protein, Soy Protein): For those who need to supplement their protein intake, plant-based protein powders like pea protein and soy protein are excellent options. Pea protein, while incomplete on its own, has a good amino acid profile and is easily digestible. Soy protein, being a complete protein, is a great choice for vegans and vegetarians.

Since many plant-based proteins are incomplete, combining different protein sources can ensure you get all the essential amino acids your body needs. Protein combining refers to pairing plant-based foods that complement each other’s amino acid profiles. This is especially important for vegetarians and vegans, though it’s not necessary to combine proteins in every meal, and consuming a variety of plant-based foods throughout the day will increase your chance of consuming the complete amino acid profile. Please don’t be a plant based dieter who ends up just eating bread products and other grain based products. You can eat a protein sufficient and more nutrient dense diet with just a little bit of effort.

Common examples of protein combining include:

- Rice and Beans: Beans are low in methionine but high in lysine, while rice is the opposite, making them a perfect pair.

- Peanut Butter and Whole Grain Bread: Together, they provide a complete protein because whole grains are typically low in lysine, which peanuts provide.

- Hummus and Pita Bread: Chickpeas (in hummus) and whole grain pita form a complete protein when consumed together.

- Lentils and Brown Rice: Lentils are rich in lysine but lack sufficient methionine, while brown rice is higher in methionine but lower in lysine. Together, they provide a full spectrum of essential amino acids.

- Corn Tortillas and Black Beans: Corn tortillas are low in lysine but high in methionine, and black beans are high in lysine but low in methionine. Together, they form a complete protein, commonly seen in dishes like bean tacos.

- Oats and Almonds: Oats are low in lysine but high in methionine, while almonds provide lysine. Combining oats with almond butter or a handful of almonds makes for a protein-complete meal.