It’s 3pm on a Thursday afternoon. You’re sitting at your desk, eyes heavy, mind foggy, fighting the urge to put your head down right there on your keyboard. Last night was another rough one: lying awake, watching the ceiling, feeling that familiar knot of anxiety tighten as the hours ticked by. And now you’re already dreading tonight, wondering if you’ll be stuck in the same exhausting cycle.

Here’s what you need to know: Yes, you can do things today (right now, this afternoon and this evening) that will genuinely help you improve sleep tonight. But I’m also going to be honest with you: one night of good sleep hygiene won’t fix chronic sleep issues. If you’ve been sleeping poorly for months or years, tonight is the beginning of something, not the solution to everything.

What I’m going to give you is a dual approach. First, the emergency protocols: the specific, actionable things you can do in the hours before bed that will actually make a difference tonight. But second, and perhaps more importantly, I’m going to help you understand how sleep actually works. Because once you understand the architecture of sleep, the systems that control it, and why most sleep advice fails, you’ll have the knowledge and agency to build sustainable, restorative sleep for the long term.

Unfortunately, with all of this sleep stuff, sometimes trying too hard to sleep is precisely what prevents it. Sleep requires surrender. You cannot force it. You can only create the conditions, then trust your biology to do what it’s designed to do.

TL;DR

You’re exhausted right now, and you want to sleep better tonight. Here’s what actually matters: stop drinking caffeine after 2pm (it has a 5-6 hour half-life and blocks the adenosine that makes you sleepy). Don’t nap today: you need to build sleep pressure. Get bright light exposure right now if it’s still daylight, then dim your lights after 8pm to signal to your body that night is coming. Start winding down early, around 7 or 8pm, not at 10:30pm when you expect to sleep; your nervous system needs time to down-regulate and can’t flip a switch from high arousal to sleep. Take a warm shower about 90 minutes before bed so your body temperature drops afterward, which triggers sleepiness. Skip the alcohol: it might help you fall asleep but it absolutely ruins the second half of your night by fragmenting sleep and suppressing REM. Don’t eat a big meal in the 2-3 hours before bed. If you can’t fall asleep within 15-20 minutes, get out of bed and do something boring in dim light until you feel genuinely sleepy, then try again.

But here’s what you really need to understand: one night of good sleep hygiene won’t fix chronic sleep problems. What will fix it is consistency: same bedtime and wake time every single day (yes, including weekends), morning light exposure within an hour of waking, caffeine cutoff by 2pm, and an evening wind-down routine. Sleep requires surrender, not effort. You can create the conditions, but you cannot force it. Get the basics right for 2-4 weeks and your sleep will genuinely improve.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 Understanding How Sleep Actually Works

- 3 The Arousal Problem: Why “Just Relax” Doesn’t Work

- 4 What You Can Do Right Now (This Afternoon and Evening)

- 5 The 15-Minute Rule: What to Actually Do If You Can’t Sleep

- 6 What Won’t Help Tonight (But Might Feel Tempting)

- 7 Technology: Friend or Foe?

- 8 Building Sustainable Sleep (Beyond Tonight)

- 9 How To Improve Sleep Tonight Conclusion: Tonight, Tomorrow, and Beyond

- 10 Author

Understanding How Sleep Actually Works

Most sleep advice jumps straight to “tips and tricks” without helping you understand what’s actually happening when you sleep. That’s a mistake. When you understand the architecture of sleep and the systems controlling it, everything else makes sense. The advice stops feeling arbitrary and starts feeling intuitive.

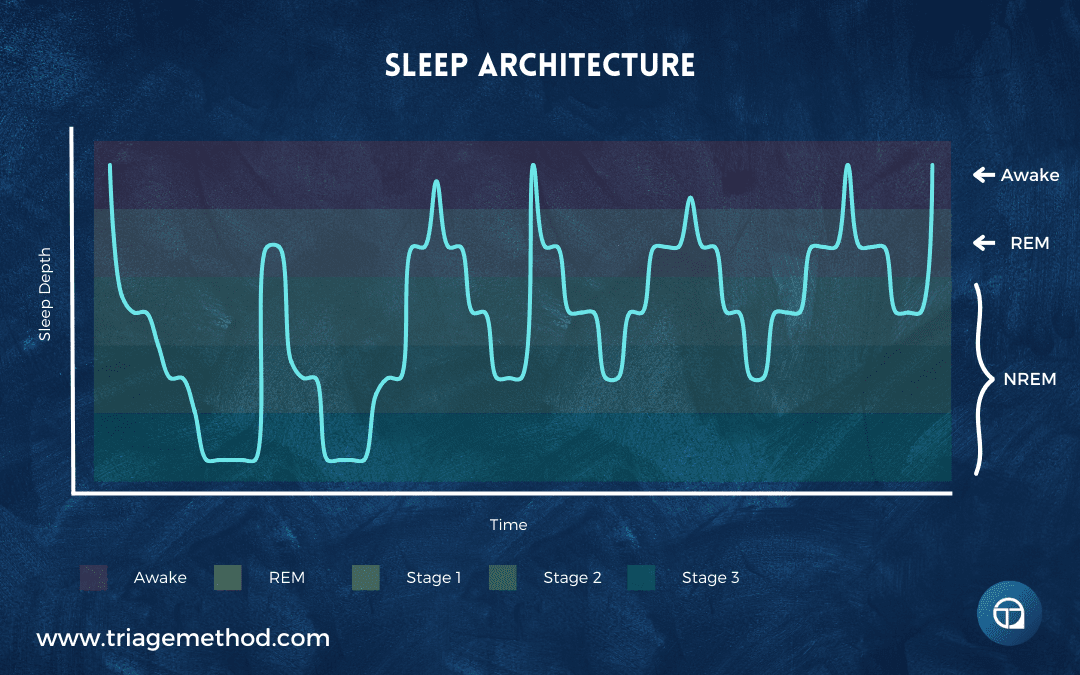

The Architecture of a Good Night’s Sleep

Sleep isn’t a uniform state you slip into for eight hours. It’s structured, cyclical, and remarkably complex. Throughout the night, you cycle through different stages: light sleep, deep sleep, and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. This cycle repeats roughly every 90 minutes, so in an eight-hour night, you’re moving through about four to six complete cycles.

What matters practically is that these stages serve different functions, and they’re not evenly distributed across the night. The first half of your night is rich in deep sleep: this is when your body does the heavy lifting of physical restoration, immune system maintenance, and metabolic regulation. The second half of the night is disproportionately rich in REM sleep: this is when your brain processes emotions, consolidates memories, and makes creative connections.

This structure is ancient and non-negotiable. You can’t hack your way around it. Which means that six hours of sleep isn’t just 25% less than eight hours, you’re getting proportionally less of that crucial REM sleep in the second half of the night. It’s why you can sleep six hours and wake feeling not just tired, but cognitively fuzzy and emotionally fragile.

Understanding this architecture also explains why certain interventions work or don’t work. Alcohol, for instance, might help you fall asleep faster and might even deepen that first part of the night. But as your body metabolises the alcohol in the second half of the night, your sleep becomes fragmented and your REM sleep is suppressed. You’ve traded the most cognitively restorative portion of your night for the illusion of easy sleep onset. You’ll “sleep” eight hours and wake feeling unrefreshed, irritable, and mentally sluggish.

The Two Systems That Control Sleep

Your sleep is governed by two interacting systems, and if you want to improve sleep tonight (or any night) you need to understand both of them.

Sleep Pressure (Process S): Think of this as a steadily building biological pressure to sleep. From the moment you wake up, a chemical called adenosine begins accumulating in your brain. The longer you’re awake, the more adenosine builds up, and the stronger your drive to sleep becomes. This is sleep pressure. When you finally sleep, adenosine is cleared, and you wake with the pressure reset to zero.

Circadian Rhythm (Process C): This is your internal biological clock, a roughly 24-hour rhythm that’s primarily regulated by light exposure. Your circadian rhythm controls not just when you feel sleepy and when you feel alert, but also your body temperature, hormone release, and countless other physiological processes. It’s why you feel naturally sleepy around the same time each night (if you’re consistent) and why you tend to wake around the same time each morning even without an alarm.

These two systems work together. When you have strong sleep pressure (you’ve been awake long enough, adenosine has accumulated) and your circadian rhythm is signalling that it’s nighttime (you’ve had appropriate light exposure during the day and darkness in the evening), you fall asleep easily and sleep soundly.

Modern life works against both systems. Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, artificially reducing your perception of sleep pressure even though the pressure is still building underneath. Artificial light in the evening confuses your circadian rhythm, signalling “daytime” when it should be receiving “nighttime” cues. Irregular schedules like staying up late on Friday and Saturday, sleeping in on Sunday morning, are constantly resetting your circadian clock, and creating a perpetual state of internal jet lag.

This matters for improving your sleep tonight because you can manipulate both systems today to improve sleep tonight. You can protect your sleep pressure by avoiding caffeine this afternoon and not napping. You can strengthen your circadian signal by getting bright light exposure now and dimming lights this evening. These aren’t tips and tricks; they’re working with your biology to encourage sleep.

The Arousal Problem: Why “Just Relax” Doesn’t Work

There’s a common piece of sleep advice that’s worse than useless: “Just relax.” If you’re lying in bed, heart racing, mind spinning, worrying about tomorrow’s meeting or replaying today’s awkward conversation, telling yourself to “just relax” achieves precisely nothing. In fact, it often makes things worse. Now you’re anxious about sleep and frustrated that you can’t just calm down on command.

Here’s what’s actually happening: your nervous system exists on a spectrum from low arousal (calm, parasympathetic dominance) to high arousal (activated, sympathetic dominance). If you’re in a state of high arousal at 10pm when you’re trying to sleep, that’s not a switch you can flip in fifteen minutes. You needed to start down-regulating hours ago.

Think about your evening trajectory. Where are you on the arousal spectrum at 6pm? At 8pm? By 10pm? If you’re working intensely until 9:30pm, sending stressful emails, checking the news, watching a thriller, scrolling through arguments on social media, you’re maintaining or even increasing your arousal state right up until you’re supposed to sleep. Then you get into bed, expect your nervous system to immediately shift into low gear, and feel frustrated when it doesn’t comply.

Your nervous system doesn’t work that way. It needs time to down-regulate. It needs a gradual transition from the activation of the day to the calm required for sleep.

Here’s the practical implication: sleep problems often aren’t about bedtime – they’re about your entire evening. If you can’t fall asleep, the intervention isn’t “try harder to relax at 10:30pm.” The intervention is “start your wind-down at 7 or 8pm.” Lower the lights. Lower the intensity of your activities. Take a walk. Read fiction. Have a calm conversation. Stretch. Do something genuinely boring. Let your nervous system discharge the activation of the day rather than trying to suppress it.

This is why going for a walk often helps more than lying in bed “trying to relax.” You’re giving your body permission to move, to discharge some of that pent-up arousal, rather than lying perfectly still trying to will yourself into calmness.

This reframes the problem entirely. You’re not “bad at sleeping” or “bad at relaxing.” You’re trying to force your nervous system to do something it’s not ready to do yet. Give it the time and the conditions it needs, and sleep becomes easier.

What You Can Do Right Now (This Afternoon and Evening)

Right then. You want to improve sleep tonight. It’s the middle of the afternoon or early evening, and you’re reading this hoping for something, anything, that will help. Here’s what you can actually do, right now, that will make a genuine difference.

If You Can’t Fall Asleep (Sleep Onset Issues)

This is the most common complaint: you’re tired, you get into bed, and then… nothing. You lie there. Your mind spins. You check the clock. An hour passes. Two hours. You’re exhausted but somehow can’t cross over into sleep.

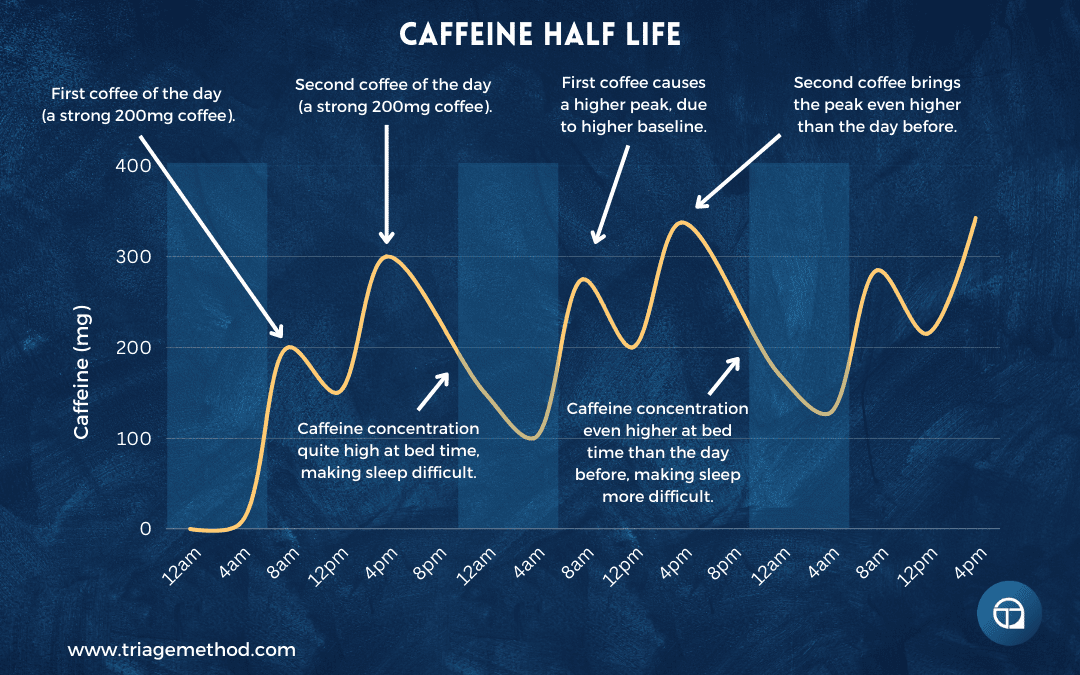

Caffeine cut-off (do this now): If you haven’t already had your last coffee of the day, make it your last one now. Full stop. No more caffeine after 2pm at the absolute latest. If you’re particularly sensitive to caffeine, make it noon.

Here’s why this matters: caffeine has a half-life of five to six hours. That means if you have a strong coffee at 4pm, half of that caffeine is still in your system at 10pm. A quarter of it is still there at 4am. Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors, and as you will remember, adenosine is the chemical that builds sleep pressure. So that afternoon coffee isn’t just giving you a boost now, it’s artificially reducing your perception of sleepiness tonight, right when you need to feel sleepy. You might feel tired (because you are tired), but your brain isn’t getting the full adenosine signal that it’s time to sleep.

Build sleep pressure (don’t nap!): I know you’re tired. I know a nap sounds appealing. Don’t do it. Every minute you stay awake is adding to tonight’s sleep pressure. If you absolutely must nap because you’re genuinely unsafe (driving, operating machinery), keep it to 20 minutes maximum and do it before 3pm. Otherwise, tough it out. That discomfort you’re feeling is actually your friend: it’s sleep pressure building, and you want as much of it as possible by bedtime.

Light exposure strategy (act on this now): If it’s still daylight, get outside. Right now. Even if it’s cloudy, even if it’s cold, even if it’s just for ten minutes. Sit by a window if you can’t get outside. Get bright light exposure. This strengthens your circadian signal for later. Your body needs a clear distinction between day and night, and modern life, with its consistently dim indoor lighting, blurs that distinction. Bright light now helps your body understand that it’s daytime, which counterintuitively helps it understand when it’s nighttime later.

Then, when evening comes, dim the lights. You don’t need to sit in darkness, but you do need a noticeable gradient from day to evening to night. After 8pm, make your environment notably dimmer than it was during the day. Use lamps instead of overhead lights. Lower the brightness on your screens (or better yet, put them away). This isn’t about achieving perfect darkness; it’s about giving your circadian system a clear signal that day is transitioning to night.

Down-regulate your nervous system early: This is crucial and often overlooked. You cannot go from high-intensity activity at 9:30pm to sleep at 10pm. Start winding down at 7 or 8pm. Make the last few hours of your day noticeably calmer and lower-intensity than the rest of it.

What does this look like practically? After dinner, go for a gentle walk. Read something light (fiction, not work-related, not the news, and definitely not social media). Have a calm conversation. Stretch. Take a warm shower. Do some light tidying. Listen to music. The activities themselves matter less than their intensity: you want calm, you want routine, and you want your nervous system to recognise that the active part of the day is over.

Avoid: intense work, stressful emails, difficult conversations, arguments, thrilling television, action films, doom-scrolling through news, social media arguments, or vigorous exercise. All of these maintain or increase arousal when you need it to be decreasing.

Temperature manipulation: About 90 minutes before you want to sleep, take a warm shower or bath. Not scalding, just comfortably warm. This timing is important because your body needs to drop its core temperature to initiate sleep. It’s one of the physiological signals that sleep is coming. When you get out of a warm shower, your body compensates by cooling down, and that cooling triggers sleepiness. Do this too early and the effect wears off. Do it right before bed and you’re actually too warm to sleep comfortably. Ninety minutes before bed is the sweet spot.

The 2-3 hour window before bed (pay special attention to this): Don’t eat a large meal in the two to three hours before sleep. Your digestive system working hard interferes with sleep onset. If you eat dinner early or lightly and find yourself genuinely hungry before bed, a small protein-rich snack is fine (handful of nuts, some Greek yoghurt), but not a full meal.

No alcohol. I’ll explain why in detail below, but for now: even if alcohol helps you fall asleep, it will ruin the second half of your night. It’s not worth it.

Intense exercise in the evening is individual: some people tolerate it fine, others find it too activating. If you know evening training keeps you wired, don’t do it tonight. If you don’t know, experiment another time, not tonight when you’re trying to rescue your sleep.

If You Wake During the Night (Sleep Maintenance Issues)

Falling asleep is fine, but then you wake at 2am, 3am, 4am. Maybe you fall back asleep, maybe you don’t. Maybe you lie there for an hour, frustration building.

Blood sugar consideration: If you ate dinner very early (5 or 6pm) or if it was very light, low blood sugar can wake you in the early hours of the morning. Your body releases cortisol to raise blood sugar, and that cortisol can wake you up. Solution: a small protein-rich snack before bed. Not a large meal, just something to stabilise blood sugar through the night. A handful of nuts, some Greek yoghurt, a bit of cheese, etc. This isn’t necessary for everyone, but if you consistently wake in the early morning hours and your dinner was early or light, it’s worth trying.

Alcohol is the enemy here: If you want to improve sleep tonight, don’t drink alcohol this evening. Alcohol is seductive for sleep; it’s a sedative, it helps you fall asleep faster, and it reduces the anxiety about whether you’ll sleep. But it absolutely ruins the second half of your night.

Alcohol suppresses REM sleep and causes fragmented, lighter sleep as your body metabolises it. You might “sleep” for eight hours, but the quality is poor. You wake feeling groggy, unrefreshed, irritable, and mentally sluggish. That’s not a hangover from excessive drinking, this happens even with small to moderate amounts. The sleep disruption is dose-dependent (more alcohol, worse sleep) but even one or two drinks can affect sleep architecture.

If you do drink, earlier is better than later, and less is better than more. But for tonight, if you’re serious about sleeping well, skip it.

Bedroom environment: Your bedroom should be cool (16-19°C is optimal for most people), properly dark (blackout curtains or an eye mask if necessary), and quiet (earplugs or white noise if you need them). You can’t always control external noise, but you can control curtains and temperature.

If you do wake: Don’t check the time. Looking at the clock creates anxiety (“It’s 3am, I’ve only got four hours left, I need to get back to sleep RIGHT NOW”) which makes it harder to fall back asleep. Don’t turn on bright lights; if you need to use the toilet, keep it dim. Don’t start mentally problem-solving or planning tomorrow’s tasks. Don’t reach for your phone.

Just lie there. Breathe. Trust that you’ll fall back asleep. Most people do within 20 minutes, even if it feels longer. Your job is to rest quietly, not to force sleep. If you’re not asleep in 15-20 minutes, then get up and follow the protocol below.

If You Wake Too Early (Early Morning Awakening)

You fall asleep fine, you sleep through the middle of the night, but then you wake at 5am and that’s it. You can’t get back to sleep. You lie there until your alarm, feeling frustrated and tired but unable to sleep.

This afternoon: Get more physical activity if possible. Even a 20-minute walk. Build more sleep pressure. The more active you are during the day, the stronger your drive to sleep will be.

This evening: Keep lighting especially dim in the final two hours before bed. Strengthen that circadian signal. You want your body to clearly understand that night is coming and sleep should extend into the morning.

Avoid going to bed too early: I know you’re tired. I know going to bed two hours earlier sounds appealing. Don’t do it. It often backfires – you’re not sleepy enough yet, you lie awake, you create anxiety, and you often wake even earlier the next morning. Maintain your normal bedtime.

Early morning awakening can also be a signal of stress, anxiety, or depression. If this pattern persists despite good sleep hygiene, it’s worth exploring with a professional.

Universal Principles for Tonight

These apply regardless of your specific sleep issue:

Maintain your normal bedtime: Even if you’re exhausted, even if you desperately want to “catch up,” don’t go to bed two hours earlier than usual. You’re probably not sleepy enough yet (insufficient sleep pressure), you’ll likely lie awake creating anxiety, and you may disrupt your circadian rhythm. Stick to your normal time.

Close the cognitive loops: One of the biggest barriers to sleep is a mind that won’t shut off. You’re lying there mentally rehearsing tomorrow’s presentation, composing emails, planning your to-do list, worrying about things you can’t control. Before you get into bed, spend five minutes writing these things down. Get them out of your head and onto paper. You don’t need to solve them, you just need to acknowledge them and set them aside. This simple act of closing the cognitive loops often makes an enormous difference.

Bedroom equals sleep and sex, nothing else: Don’t work in bed. Don’t watch television in bed. Don’t scroll through your phone in bed. Don’t eat in bed. Don’t have difficult conversations in bed. Your brain learns through association. If your bed is associated with work, stress, arguments, and screen time, your brain won’t associate it with sleep. Keep the bed for sleep and sex only. Build that association.

The surrender paradox: You cannot force sleep. This is perhaps the most important thing to understand. You can create the conditions (the cool dark room, the comfortable bed, the tired body, the calm mind) but you cannot will yourself to sleep. Sleep comes when you stop trying. Lie there, breathe, rest, and trust that sleep will come. The more you try to force it, the more you activate your nervous system, the more you push sleep away. Create conditions, then surrender.

The 15-Minute Rule: What to Actually Do If You Can’t Sleep

Most sleep advice tells you what to do before bed. Almost none of it tells you what to actually do when you’re lying there at midnight, wide awake, and it’s clearly not working. This is that advice.

The problem with lying in bed awake is psychological and neurological. You start associating your bed with frustration, anxiety, and wakefulness rather than with sleep. Every minute you spend lying there awake is reinforcing that association. Your brain learns: bed equals lying awake feeling stressed. That’s not what you want.

Here’s the protocol, and it’s backed by decades of sleep research:

If you’re not asleep within 15-20 minutes (rough estimate, don’t clock-watch), get out of bed. Don’t lie there for an hour hoping it will happen. Get up.

Go to another room. Sit on the sofa, sit at the kitchen table, sit on the floor. Doesn’t matter where, just not in bed.

Do something genuinely boring in dim light. Read something dull, not a gripping novel, and not work material, something genuinely boring. Fold laundry. Sit quietly. The goal is not to tire yourself out or to do something productive. The goal is to do something unstimulating whilst allowing sleep pressure to build just a little bit more.

No screens. No snacks. No “productive” tasks. You’re not rewarding yourself for being awake. You’re just… being awake in a boring way, in dim light, until your body signals that it’s ready to try again.

Return to bed only when you feel genuinely sleepy. Not just tired, actually sleepy. Heavy eyelids, yawning, and difficulty keeping your eyes open. That’s your signal. Go back to bed.

If you’re still not asleep in another 15-20 minutes, repeat the process. Get up again.

This works because you’re preventing the bed-anxiety association. You’re allowing sleep pressure to build a bit more. You’re removing the performance pressure of “I MUST fall asleep NOW.” And you’re trusting that your body knows how to sleep, it just isn’t ready yet.

Mindset matters here. You’re not failing at sleep. Sleep isn’t a performance you can fail at. You’re just not ready yet. That’s all. No drama, no catastrophising, no self-criticism. You’ll be ready when you’re ready.

What Won’t Help Tonight (But Might Feel Tempting)

Let’s be honest about what doesn’t work, because when you’re desperate for sleep, you’ll try anything. Some interventions feel like they should help, or they help in the short term but harm in the long term, or they’re simply ineffective despite being widely recommended.

Alcohol: The Sleep Thief

I’ve mentioned this already, but it deserves its own section because alcohol and sleep have such a complicated relationship.

Alcohol is so appealing because it’s a sedative, it reduces anxiety, and it does help you fall asleep faster. If you’re lying in bed wound up and anxious about whether you’ll sleep, a drink or two genuinely does help you fall asleep. The effect is real. This is why so many people use alcohol as a sleep aid.

Unfortunately, alcohol ruins your sleep. It is important to understand that sedation is not sleep. When you’re sedated by alcohol, you’re not getting the full architecture of natural sleep. You’re missing deeper stages, particularly REM sleep. And as your body metabolises the alcohol, which happens in the second half of the night, your sleep becomes fragmented. You wake more frequently. You spend more time in light sleep. Your REM sleep is suppressed. You wake in the morning feeling unrefreshed, irritable, and cognitively foggy even if you technically “slept” for eight hours.

Now, one drink with dinner at 6pm probably won’t destroy your sleep. Three drinks at 9pm absolutely will. The effect is dose-dependent and timing-dependent. Earlier is better than later. Less is better than more.

But the real issue is that using alcohol to fall asleep creates a psychological dependence. You start believing you can’t sleep without it. Your anxiety about sleep increases on nights you don’t drink. You’ve created a vicious cycle.

For tonight, if you’re serious about improving your sleep, don’t drink. If you do drink, one drink maximum, finish it at least three to four hours before bed, and understand you’re making a trade-off.

Supplements and Quick Fixes

You are going to want to reach for some sort of supplement quick fix, but unfortunately, this doesn’t generally work.

Melatonin: This is perhaps the most misunderstood sleep supplement. Melatonin is a hormone that helps regulate your circadian rhythm, it signals to your body that it’s nighttime. It can be useful for shifting your circadian clock (jet lag, shift work, changing your sleep schedule). But it doesn’t directly make you sleepy, and it won’t rescue tonight.

Melatonin works over days and weeks of consistent use to shift your rhythm. Taking it tonight, once, won’t do much. And most people take far too much; 5-10mg tablets are common, but research suggests 0.3-0.5mg is often more effective. More is not better with melatonin.

If you’re taking melatonin, take it 1-2 hours before you want to sleep, at the same time every night, consistently. Don’t expect a single dose to fix tonight.

Sleeping pills: Whether prescription or over-the-counter, sleeping pills produce sedation, not natural sleep. You might be unconscious for eight hours, but your sleep architecture is disrupted. Deep sleep and REM sleep are affected. You often wake with cognitive fog, sometimes called “sleep hangover.” And you’re not addressing the root cause of your sleep problem, you’re just chemically overriding it.

Sleeping pills have their place in acute situations like grief, trauma, or for very short-term use during a crisis. They’re not a solution for chronic sleep issues. If you’re using sleeping pills regularly, you need to work with a doctor on a plan to address the underlying problem.

Magnesium, glycine, L-theanine: Various supplements are marketed for sleep. Some people find them helpful. The evidence is mixed and generally modest. They might help a little, over time, with consistent use. They won’t rescue tonight. If you want to experiment with these, do it over weeks or months, not as a one-time fix. If you do want to try supplements, then magnesium can be beneficial for some. However, don’t expect this to improve things substantially.

Behavioural Traps

Trying to “catch up” by going to bed very early: You’re exhausted. Going to bed at 8pm sounds brilliant. Don’t do it. You’re probably not sleepy enough yet as your sleep pressure hasn’t built sufficiently, and your circadian rhythm isn’t signalling sleep time yet. You’ll lie awake, you’ll create anxiety, and you’ll potentially disrupt your rhythm for tomorrow night. Maintain your normal bedtime.

Napping now: That afternoon nap steals from tonight’s sleep pressure. Every minute asleep now is one less minute of sleep pressure building for tonight. If you’re genuinely unsafe without a nap, keep it to 20 minutes maximum before 3pm. Otherwise, resist. You want to arrive at bedtime tonight with maximum sleep pressure.

Sleep trackers tonight: If you’re already anxious about sleep, the last thing you need is to obsess over whether your deep sleep was 15% or 18%, whether you woke three times or four times, whether your “sleep score” was 72 or 68. Sleep tracking can be useful for pattern recognition over weeks and months. It’s counterproductive when you’re anxious about tonight. Put the tracker away. Focus on how you actually feel, not what a device tells you you should feel.

Technology: Friend or Foe?

The standard advice of “no screens before bed” is simplistic and often impractical. Most people aren’t going to read by candlelight for two hours every evening. So what actually matters here?

The problem with screens isn’t just the blue light, though that is part of it. Blue light suppresses melatonin and signals “daytime” to your circadian system. But the more significant issue is often what you’re doing on the screen and how engaging it is.

What actually matters:

The content: Doom-scrolling through news about disasters, getting into arguments on social media, watching a thriller or horror film, checking work emails that stress you out, or reading content that makes you angry or anxious, all create arousal. Your nervous system doesn’t distinguish between a real threat and a perceived threat. Enraging social media content activates you just as a real argument would. Watching a tense film activates your stress response just as a real dangerous situation would.

Compare that to reading a boring Kindle book with the brightness turned down, or watching something genuinely calm and familiar. The arousal level is completely different.

The light exposure: Yes, bright screens in the evening do signal “daytime” to your circadian system. But it’s dose-dependent. Two hours of bright screen time in your face is different from 20 minutes of a dimmed phone. Context matters.

The engagement: Passive watching (television) is different from interactive scrolling (phone). Interactive screens tend to be more engaging, more activating, and harder to put down.

Practical approach for tonight:

In an ideal world, you would have screens off one to two hours before bed. Read a book, have a conversation, stretch, take a bath, do something offline.

But I know most of you won’t or can’t do that, so what I will often advise my clients to do is dim the screens significantly (use night mode, turn brightness to minimum), avoid high-arousal content (no news, no arguments, no thrillers), stop at least 30-60 minutes before bed, and favour passive over interactive screen time.

Tools that might help: f.lux or Night Shift on your devices automatically reduce blue light in the evening. Blue-blocking glasses are popular, though the evidence is mixed (they’re unlikely to hurt, they might help a bit, don’t expect miracles). Screen dimmers (software that makes your screen darker than the minimum brightness setting) can be useful.

Sleep trackers:

Sleep trackers can be genuinely useful for recognising patterns over weeks and months. “I notice I sleep poorly every time I have coffee after 3pm” or “I sleep better on nights I exercise” – that’s valuable information.

But sleep trackers become problematic when you obsess over nightly data. Your tracker says you only got 52 minutes of deep sleep last night instead of your usual 72. Now you’re anxious all day. You feel like you should feel worse than you actually do. You start catastrophising.

But the truth is that consumer sleep trackers are imperfect. They estimate sleep stages, they don’t measure them with anything approaching the accuracy of a proper sleep study. They’re often wrong. And even when they’re directionally correct, the numbers they give you are less important than how you actually feel.

If your tracker says you had poor sleep but you feel fine, trust how you feel. If checking your sleep score creates anxiety, ditch the tracker. If it helps you spot patterns and make better choices without creating stress, keep using it.

There’s even a term for unhealthy obsession with sleep data: orthosomia. Don’t develop orthosomia. Sleep is not a performance to be optimised to the third decimal place. It’s a biological process that serves your life. The goal is to feel rested and function well, not to achieve a perfect sleep score.

Building Sustainable Sleep (Beyond Tonight)

Right. You now understand how sleep works. You know what to do tonight. But if you want to actually solve your sleep problem and not just put a plaster on it for one night, you need to build sustainable habits. These aren’t sexy, they’re not hacks, they’re just what works.

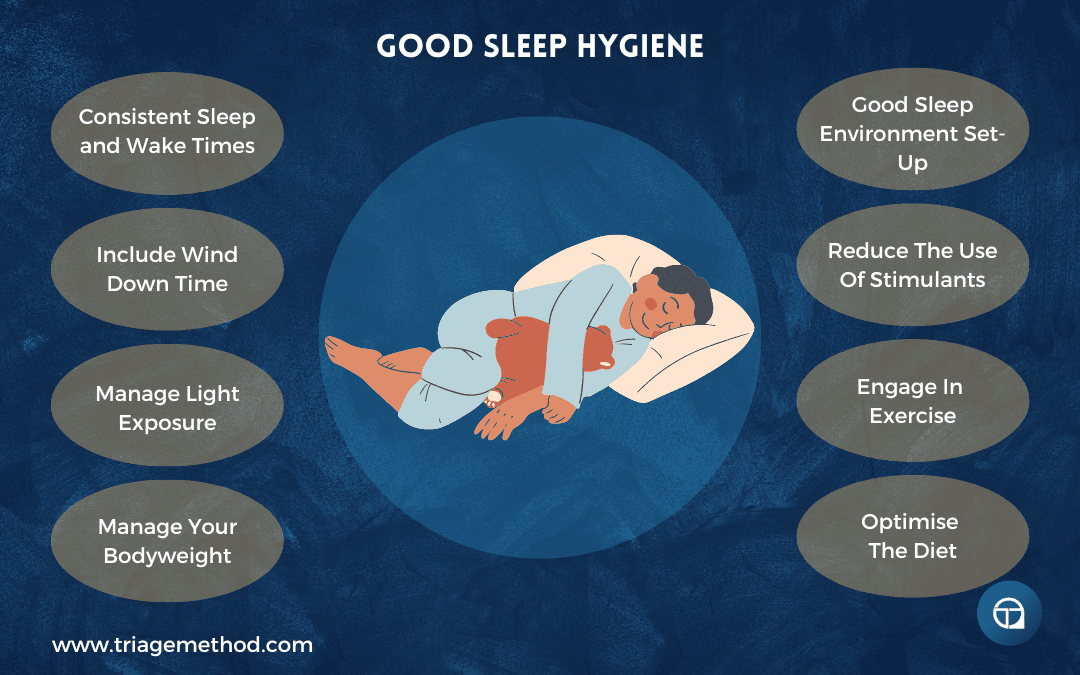

The Non-Negotiables

1. Consistent sleep and wake times (even weekends)

This is the single most powerful intervention you can make for your sleep. Your circadian rhythm thrives on predictability. It wants to know when daytime is and when nighttime is. When you go to bed at 11pm on weeknights but 2am on weekends, then sleep until noon on Sunday, you’re essentially giving yourself jet lag. Your circadian clock doesn’t know what time zone you’re in.

This phenomenon of staying up late and sleeping in on weekends, then struggling to adjust back to your weekday schedule, is called social jet lag. It disrupts your sleep for days. Monday and Tuesday you feel awful because your circadian rhythm is still trying to figure out what’s happening.

Pick sleep and wake times you can actually maintain seven days a week. Yes, this might mean leaving parties early on Saturday night. Yes, this might mean setting an alarm on Sunday morning even when you could sleep in. These are the trade-offs.

If you want good sleep, consistency is non-negotiable. Full stop.

2. Morning light exposure

Within 30 to 60 minutes of waking, get outside or near a window. Get bright light exposure for 10 to 30 minutes. This sets your circadian clock. It tells your body: this is morning, this is when the day starts, nighttime will be approximately 16 hours from now.

Even on a cloudy day, outdoor light is 10 to 100 times brighter than indoor lighting. Your circadian system needs that brightness to function properly. Indoor lighting alone isn’t sufficient.

This morning light exposure is arguably as important as anything you do at bedtime. It’s the anchor point for your entire circadian rhythm. Skip this consistently, and your circadian clock drifts. You’ll find it harder to fall asleep at night and harder to wake in the morning.

If you genuinely cannot get outside (shift worker sleeping during the day, winter in a northern latitude with very late sunrise), consider a light therapy box. But for most people, most of the time: get outside in the morning. Make it a priority.

3. Caffeine strategy

Caffeine has a half-life of five to six hours. This is not negotiable. This is biology. If you have a strong coffee at 4pm, half of that caffeine is still in your system at 10pm. A quarter of it is still there at 4am.

Last caffeine by 2pm at the latest. If you’re particularly sensitive, make it noon. Pay attention to total dose as well: five strong coffees by noon is still a lot of caffeine coursing through your system all day.

Some people claim caffeine doesn’t affect them. They can drink coffee at 8pm and fall asleep by 10pm. Perhaps. But research suggests that even when people fall asleep normally, caffeine in their system disrupts sleep architecture. They have lighter sleep, more awakenings, and less restorative sleep overall. You might not notice the effect subjectively, but your sleep quality is still impacted.

If you’re serious about improving your sleep, respect caffeine’s half-life. Cut it off early.

4. Evening wind-down routine

Create a consistent sequence of calming activities in the hour or two before bed. Same activities, same order, same time each night. This signals to your brain: day is ending, sleep is coming.

Your routine doesn’t need to be elaborate. Shower, read for 20 minutes, bed. That’s fine. Or: tidy kitchen, stretch for ten minutes, write in journal, dim lights, read, bed. The specifics matter less than the consistency.

Your brain learns through repetition and association. When you do the same calming sequence every night, your brain starts anticipating sleep as the routine unfolds. By the time you’re at the end of the routine, your body is already preparing for sleep.

Contrast this with what many people do: wildly inconsistent bedtimes, no routine at all, or a “routine” that includes high-arousal activities like working until ten minutes before bed, scrolling social media in bed, or watching intense television.

Build a routine. Stick to it. Every night, even weekends. Your brain will thank you.

5. Exercise timing and intensity

Regular physical activity improves sleep. It builds sleep pressure, it helps regulate your circadian rhythm, it reduces anxiety and stress. Exercise is one of the best things you can do for sleep.

Timing matters for some people but not others. The traditional advice is “don’t exercise late in the evening” because it’s too activating. For some people, that’s true; an intense workout at 8pm means they’re still wired at 11pm. For others, evening exercise is fine or even helpful.

If you’re not sure, experiment. If you know evening exercise disrupts your sleep, move it earlier in the day. If evening is the only time you can train and it doesn’t seem to bother your sleep, carry on.

One nuance: exhausting yourself doesn’t guarantee better sleep. Sometimes, very intense training actually creates too much arousal and your nervous system is activated, cortisol is elevated, and you struggle to wind down. Listen to your body. Most people find that regular, moderate exercise improves sleep more reliably than sporadic intense sessions.

6. Bedroom environment

Your bedroom should be cool, dark, and quiet.

Cool: 16-19°C is optimal for most people. Your body needs to drop its core temperature to initiate and maintain sleep. If your room is too warm, you’ll struggle. If you wake up sweating, your room is too warm. Use fans, open windows, adjust heating. Temperature matters more than most people realise.

Dark: Properly dark. Not just lights off; blackout curtains or an eye mask. Even small amounts of light can disrupt sleep for some people. If you wake to use the toilet in the night, use a dim night light or torch, not bright overhead lights.

Quiet: If external noise is an issue (traffic, neighbours, partner who snores), use earplugs or a white noise machine. You can’t always control external noise, but you can control how it reaches you.

Comfortable: This seems obvious, but people tolerate terrible mattresses and pillows for years. If your bed is uncomfortable, you won’t sleep well. Full stop. Invest in decent bedding. You spend a third of your life in bed, so it’s worth getting right.

And reserve your bed for sleep and sex only. Not work, not television, not scrolling, not eating. Build the association: bed equals sleep.

The Hierarchy: Don’t Major in the Minors

What often happens is that someone is sleeping poorly, so they start researching sleep optimisation. They discover there are supplements that might help by 5%, sleep trackers that monitor their REM percentage to the second decimal place, mouth tape to encourage nasal breathing, cold plunges to manipulate core temperature, special pillows to align their spine perfectly, blue-blocking glasses, sunrise alarm clocks, weighted blankets, magnesium glycinate vs. magnesium threonate, sleep apnoea screening, genetic testing for chronotype…

And they’re still going to bed at different times every night, still drinking coffee at 4pm, still scrolling their phone in bed, still keeping their bedroom at 22°C with light leaking through the curtains.

Don’t do this. Don’t major in the minors.

If you’re not doing the basics consistently – consistent schedule, morning light, sensible caffeine strategy, wind-down routine, appropriate bedroom environment – then supplements, gadgets, and advanced protocols are a waste of time and money. They’re like polishing the paintwork on a car with no engine.

Get the foundation solid first. Six weeks of truly consistent sleep and wake times, proper light exposure, reasonable caffeine habits, and a calming evening routine will do more for your sleep than a thousand pounds worth of supplements and devices.

Then, if you’ve got the basics down and you’re still struggling, explore the marginal gains. But not before.

Timeline and Patience

If you’ve been sleeping poorly for months or years, don’t expect to fix it in three days. Sustainable improvement takes time.

You might feel noticeably better within a week of implementing good sleep hygiene. But real improvement in your sleep architecture (the deep changes in how you sleep) takes two to four weeks of consistency. Your body is adapting. Your circadian rhythm is stabilising. Your sleep pressure system is recalibrating.

Be patient. Trust the process. Keep showing up. Consistency matters more than perfection. A few imperfect nights don’t undo your progress, but abandoning the whole effort after one setback does.

How To Improve Sleep Tonight Conclusion: Tonight, Tomorrow, and Beyond

So here we are. You’re reading this because you want to improve sleep tonight and I’ve given you the tools.

For tonight:

Cut off caffeine early, if you haven’t already, no more after 2pm. Build sleep pressure: don’t nap. Get light exposure now if it’s still daylight. Start winding down early, by 7 or 8pm, lower the intensity. Use temperature strategically: have a warm shower 90 minutes before bed. Avoid large meals, alcohol, and high-arousal activities in the final 2-3 hours. Dim the lights. Close the cognitive loops: write down tomorrow’s worries. Get into bed at your normal time. Create conditions, then surrender.

If you can’t sleep in 15-20 minutes, get up. Do something boring in dim light. Return when sleepy. Repeat if needed. Don’t lie in bed building anxiety.

Understand the architecture: Sleep cycles through light, deep, and REM stages. First half is rich in deep sleep for physical restoration. Second half is rich in REM for cognitive and emotional processing. This structure is non-negotiable.

Remember the systems: Sleep pressure builds throughout the day (adenosine). Your circadian rhythm is set by light exposure. Work with both systems.

Remember the arousal spectrum: If you’re wired at bedtime, you needed to start winding down hours earlier. You can’t flip a switch. Down-regulate your nervous system progressively through the evening.

Be honest about what won’t help: Alcohol sedates but fragments sleep. Supplements won’t rescue tonight. Trying too hard creates performance anxiety.

But look beyond tonight:

Sustainable sleep comes from consistent daily rhythms. The non-negotiables: consistent sleep and wake times (even weekends), morning light exposure, caffeine cut-off by 2pm, evening wind-down routine, optimised bedroom environment.

Build pattern recognition. Notice what actually affects your sleep over weeks and months. Don’t obsess over individual nights.

Major in the majors. Get the basics solid before optimising supplements or gadgets. The basics will do more for you than anything else.

Be patient. Real improvement takes 2-4 weeks of consistency. Trust the process.

You can’t force sleep, you can only create conditions and trust. Sleep requires surrender. Building good sleep requires discipline. You need to care enough to implement good habits, but not so much that you create anxiety. Tonight matters, but one night is just one night.

What to do right now:

Choose two or three things from this article to implement today. Not all of them, that’s often overwhelming. Start small. Build from there.

For most people, I’d suggest: Caffeine cut-off by 2pm. Dim lights after 8pm. And have a warm shower.

Implement those. See how it goes tonight. Keep them in for a week. Notice patterns. Adjust. Add another habit when you’re ready.

Ultimately, you want to sleep well to have the energy and clarity to live as you want to live. Every hour of good sleep is an investment in your capacity to be present, patient, focused, connected. To show up as your best self rather than your most depleted self. To engage with your life rather than just surviving it.

Your sleep choices are choices about who you’re becoming and how you want to move through the world. This isn’t about perfection or obsessive optimisation. It’s about building the foundation that makes everything else possible. It’s about having the capacity to flourish.

You have more agency here than you think. You’re not powerless. You’re not doomed to poor sleep forever. You can change this. Start tonight. Keep going tomorrow. Build consistency. Trust yourself.

If you need more help with your own lifestyle, you can always reach out to us and get online coaching, or alternatively, you can interact with our free content, especially our free sleep content.

If you want more free information on sleep, stress management, nutrition or training, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too, such as a sleep course that you may be interested in. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

References and Further Reading

Gardiner C, Weakley J, Burke LM, et al. The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2023;69:101764. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36870101/

Reichert CF, Deboer T, Landolt HP. Adenosine, caffeine, and sleep-wake regulation: state of the science and perspectives. J Sleep Res. 2022;31(4):e13597. doi:10.1111/jsr.13597 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35575450/

Gardiner C, Weakley J, Burke LM, et al. The effect of alcohol on subsequent sleep in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2025;80:102030. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2024.102030 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39631226/

Ebrahim IO, Shapiro CM, Williams AJ, Fenwick PB. Alcohol and sleep I: effects on normal sleep. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(4):539-549. doi:10.1111/acer.12006 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23347102/

Colrain IM, Nicholas CL, Baker FC. Alcohol and the sleeping brain. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;125:415-431. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00024-0 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5821259/

Stein MD, Friedmann PD. Disturbed sleep and its relationship to alcohol use. Subst Abus. 2005;26(1):1-13. doi:10.1300/j465v26n01_01 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2775419/

Blume C, Garbazza C, Spitschan M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie (Berl). 2019;23(3):147-156. doi:10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6751071/

Crowley SJ, Eastman CI. Phase advancing human circadian rhythms with morning bright light, afternoon melatonin, and gradually shifted sleep: can we reduce morning bright-light duration?. Sleep Med. 2015;16(2):288-297. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25620199/

de Menezes-Júnior LAA, Sabião TDS, Carraro JCC, Machado-Coelho GLL, Meireles AL. The role of sunlight in sleep regulation: analysis of morning, evening and late exposure. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):3362. Published 2025 Oct 6. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-24618-8 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12502225/

Patel AK, Reddy V, Shumway KR, et al. Physiology, Sleep Stages. [Updated 2024 Jan 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526132/

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research; Colten HR, Altevogt BM, editors. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006. 2, Sleep Physiology. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19956/

Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:586-604. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.010 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28757454/

Alhola P, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(5):553-567. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2656292/

Haghayegh S, Khoshnevis S, Smolensky MH, Diller KR, Castriotta RJ. Before-bedtime passive body heating by warm shower or bath to improve sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;46:124-135. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.008 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31102877/

Tai Y, Obayashi K, Yamagami Y, et al. Hot-water bathing before bedtime and shorter sleep onset latency are accompanied by a higher distal-proximal skin temperature gradient in older adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(6):1257-1266. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9180 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33645499/