The goal of this foundational nutrition article is to give you a resource you can use to learn how to set up your diet using good evidence-based information and the latest science.

While we can discuss all of the nuances of nutrition and go deep down the rabbit hole of some relatively meaningless single nutrient or the benefits of certain foods or supplements etc., ultimately, we need to actually have a clear overview of what a good diet looks like with broad strokes. You need to have a good general foundational diet structure before you even begin to look into any fancy or advanced protocols.

If you learn the principles behind nutrition, rather than just learning about protocols, you will be able to make much better dietary decisions, and you will be less likely to fall for dodgy diet marketing. However, in trying to provide a relatively short synopsis of how to set up your diet, we, naturally enough, can’t go into extreme detail on every single thing and we certainly can’t cover all the nuances of good nutrition, but we do think by the end of this article, you will have a very good grasp of nutrition in general.

Understanding how to set up your diet properly is the key to actually getting the results you want. Too many people get caught up in trying to follow rigid diet plans, only to burn out after a few weeks. Instead, the goal should be to set up your diet in a sustainable way that fits your lifestyle, supports your goals, and is enjoyable enough to stick with in the long term.

The goal of this comprehensive article on how to set up your diet is to refine all that we have discussed in this article series into a more easily digestible format and to allow you to see the key points that will allow you to set up your diet correctly.

Table of Contents

- 1 Step 1: Determining Your Caloric Needs

- 2 Step 2: Macronutrient Breakdown

- 3 Step 3: Hydration

- 4 Step 4: Food Variety and Micronutrients

- 5 Step 5: Structuring Your Meals: Meal Timing & Distribution

- 6 Step 6: Adjusting Calories Based on Goals

- 7 Step 7: Individual Adjustments

- 8 How To Set Up Your Diet Review

- 9 Author

But before we get stuck into this, I do want you to remember, nutrition is not about perfection, it’s about consistency and making informed adjustments based on real-world feedback. So this article should just be used as a rough template for helping you to understand how to set up your diet, and it will need to be tailored to your specific needs.

So, let’s dive in and show you how to set up your diet the right way.

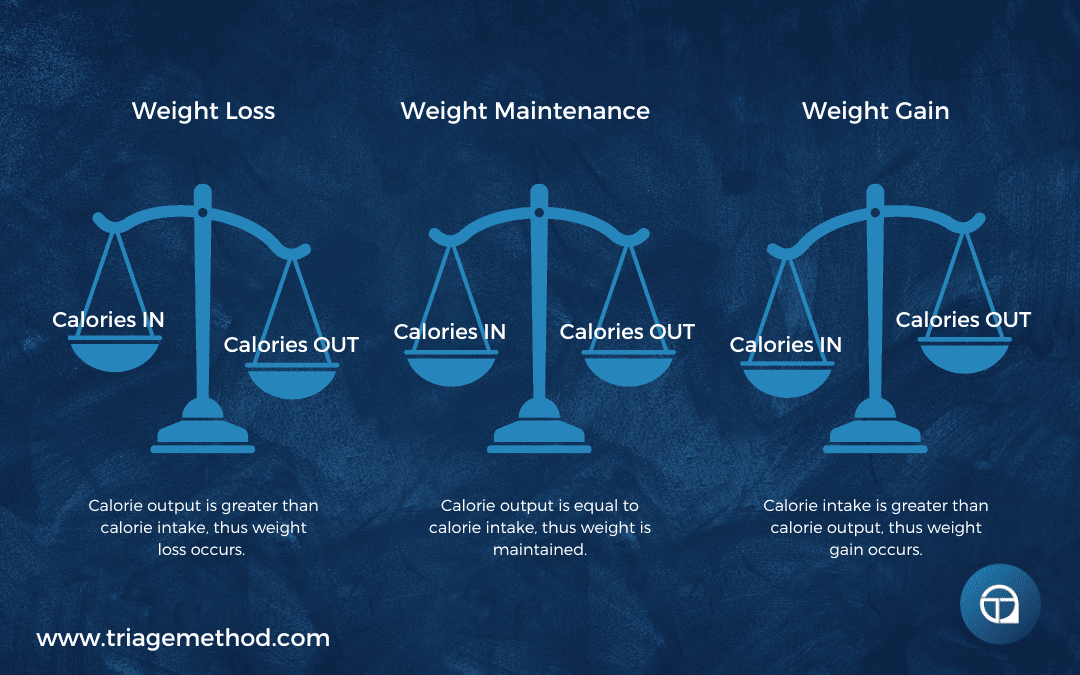

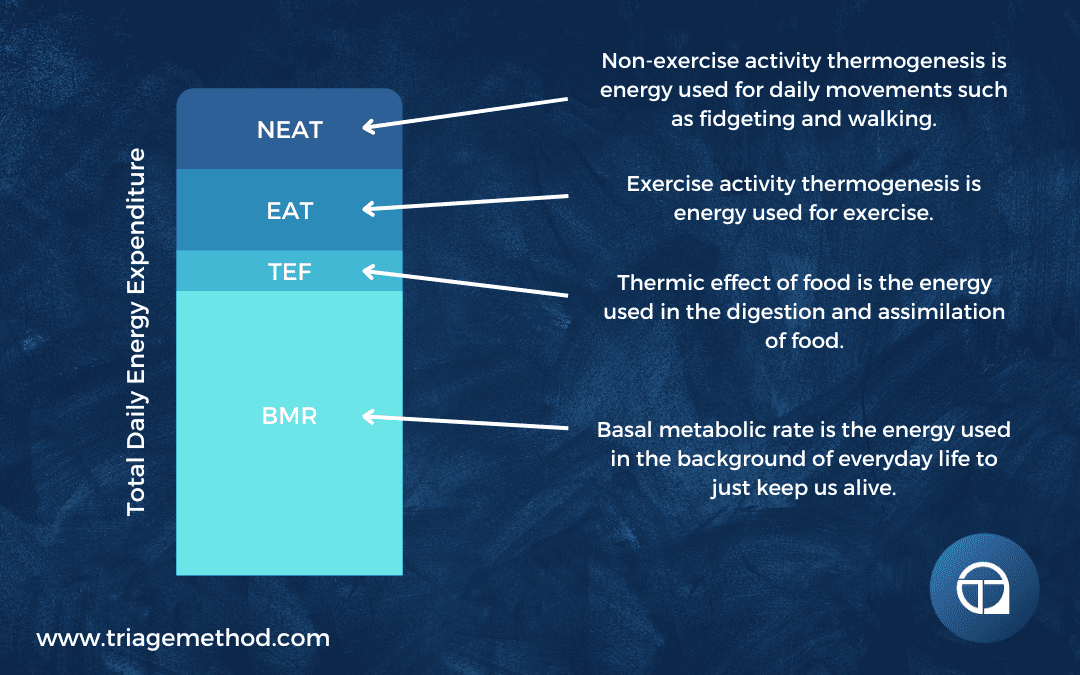

Step 1: Determining Your Caloric Needs

Calories are the foundation of your diet. Whether your goal is fat loss, muscle gain, or maintenance, understanding how to manipulate your calorie intake effectively is crucial. Many people turn to online calorie calculators to get a better idea of their calorie needs (and we do have calculators on site to help you set up your diet such as Ultimate Diet Set Up Calculator, Calorie And Macronutrient Calculator, and Macro Percentage Calculator), but the most accurate way to determine your needs is to track your current intake and observe how your body responds over time. You can use our calculator to get a starting estimate, but real-world data from your own body is far superior in refining your caloric strategy.

Tracking Your Intake

To get started, use a calorie tracking app like MyFitnessPal, Cronometer, or a similar tool to log everything you eat and drink for a minimum of one to two weeks. Accuracy is key with this. If you forget to log small snacks, condiments, or beverages, you may underestimate your total intake. Weighing food portions where possible ensures precision in your tracking. You likely don’t have the skills to “eye ball” things effectively yet, so you will need to actually weigh things.

While doing this initial tracking, continue eating as you normally would. Avoid making adjustments based on what you assume is “healthy”, because the goal here is to collect unbiased data on your habitual intake.

You should also weigh yourself every morning under consistent conditions (i.e. after using the bathroom and before eating or drinking anything). Weight fluctuations from day to day are normal due to water retention and digestion variations, so focus on the overall trend rather than any single measurement. But you will need your weight data to more accurately assess your calorie intake.

Assessing the Data

Once you have tracked your intake consistently for at least a week, you can analyse this with respect to how your weight has responded:

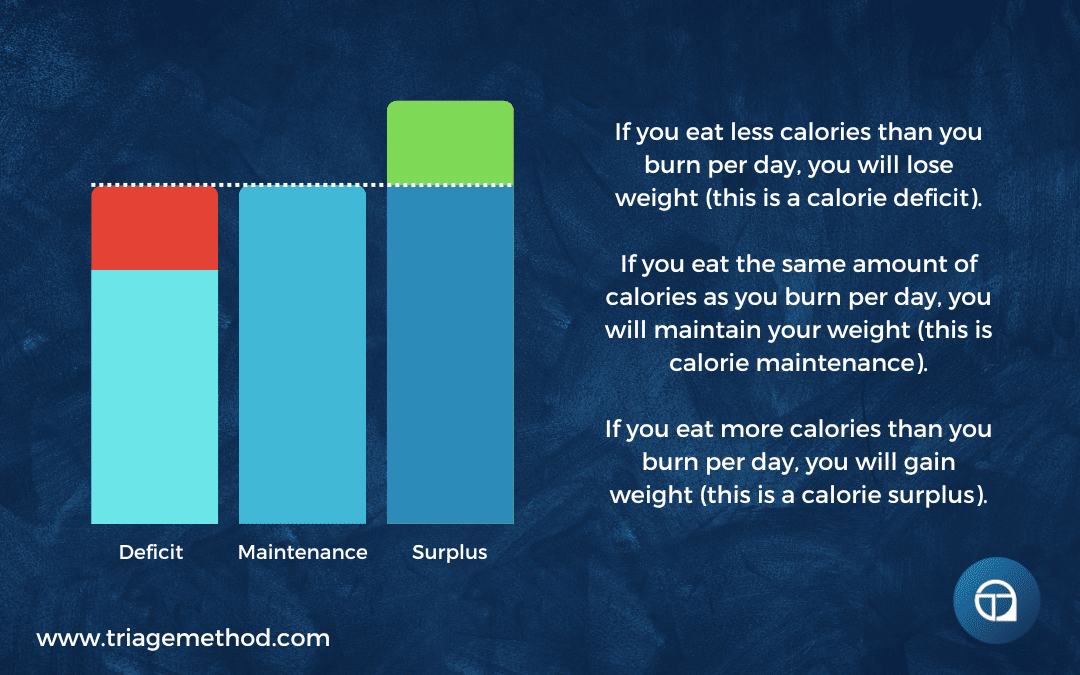

- If you are losing weight, you are in a caloric deficit, meaning you are consuming fewer calories than your body expends.

- If you are gaining weight, you are in a caloric surplus, meaning you are consuming more calories than your body needs.

- If your weight remains stable, you are at maintenance calories, meaning your intake is roughly equal to your energy expenditure.

One of the most common issues is underestimating total calorie intake. This often happens when you only track for a few days, rather than a week or two. Many people eat less during weekdays but compensate with much higher calorie consumption over the weekend. So, if you only do a short amount of data collection, you may think you are habitually consuming much fewer calories than you actually are. This is why averaging intake over multiple days (and ideally including weekend days) is essential for accuracy.

Setting an Effective Baseline

Now, you might feel like now that you know roughly how many calories you are eating and whether you are in a deficit, surplus or at maintenance, the next step is to set up your diet to really push hard towards your goals. But before you dive into a fat loss or muscle gain phase, it is generally very beneficial to first set your calories at maintenance level and focus on refining your nutrition habits.

This approach actually allows you to develop consistency in your eating patterns, optimise macronutrient distribution, and assess your body’s response to balanced nutrition.

For approximately two weeks, keep your calories at maintenance while prioritising nutrient-dense foods and actually structuring your meals and overall diet in a healthy way. You effectively want to build healthy eating habits, build the ability to accurately and consistently hit your targets and develop your knowledge and skill of eating a healthy diet. It is much harder to do this when you are in a deficit, because hunger and cravings make this more difficult. This period of maintenance helps establish a baseline from which you can make future adjustments more precisely and effectively.

I am going to continue with the steps assuming you will be following this advice, but if you wish to not follow this advice, then you can skip down to step 6 below and then come back to step 2.

If you want to learn more about calories, then we recommend: How Many Calories Should You Eat?

Step 2: Macronutrient Breakdown

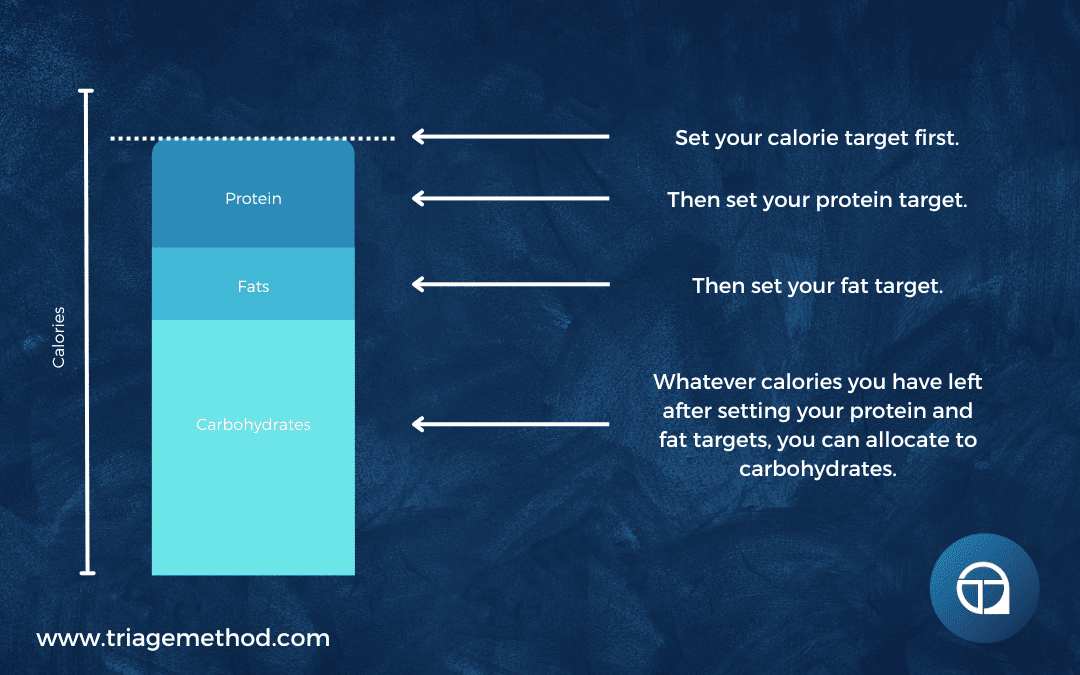

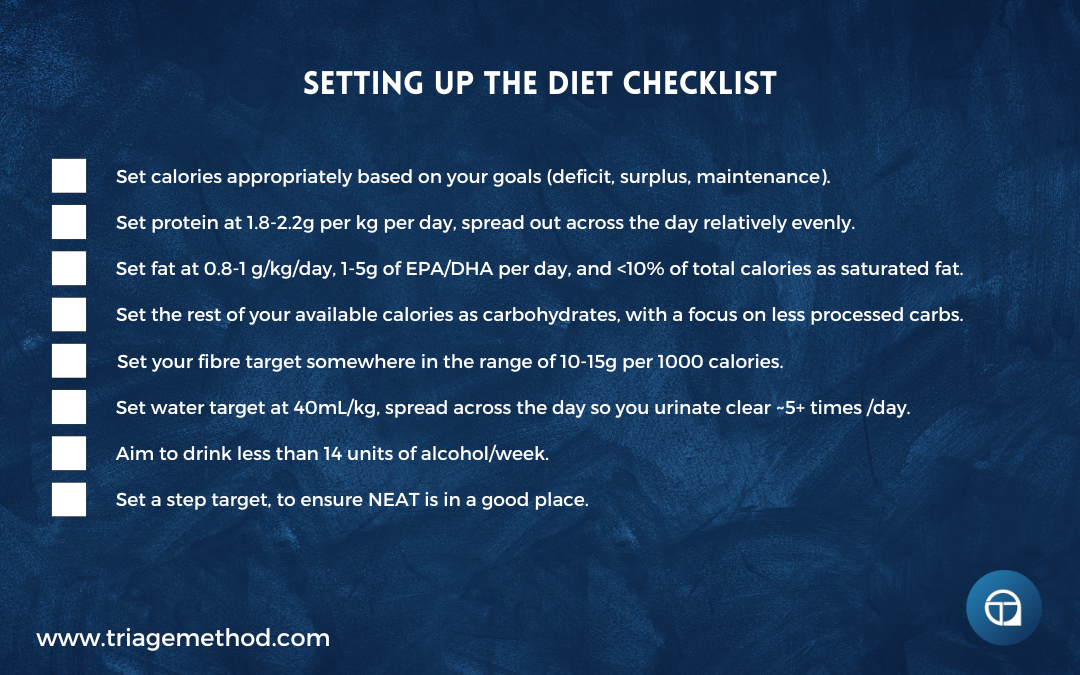

Once you know how many calories you should be eating, you can begin to actually organise your diet. The first real step is to set your macronutrient targets. There are actually many different ways you can do this, and the exact numbers can be tweaked depending on your exact goals, but the following makes sense for most people.

Protein

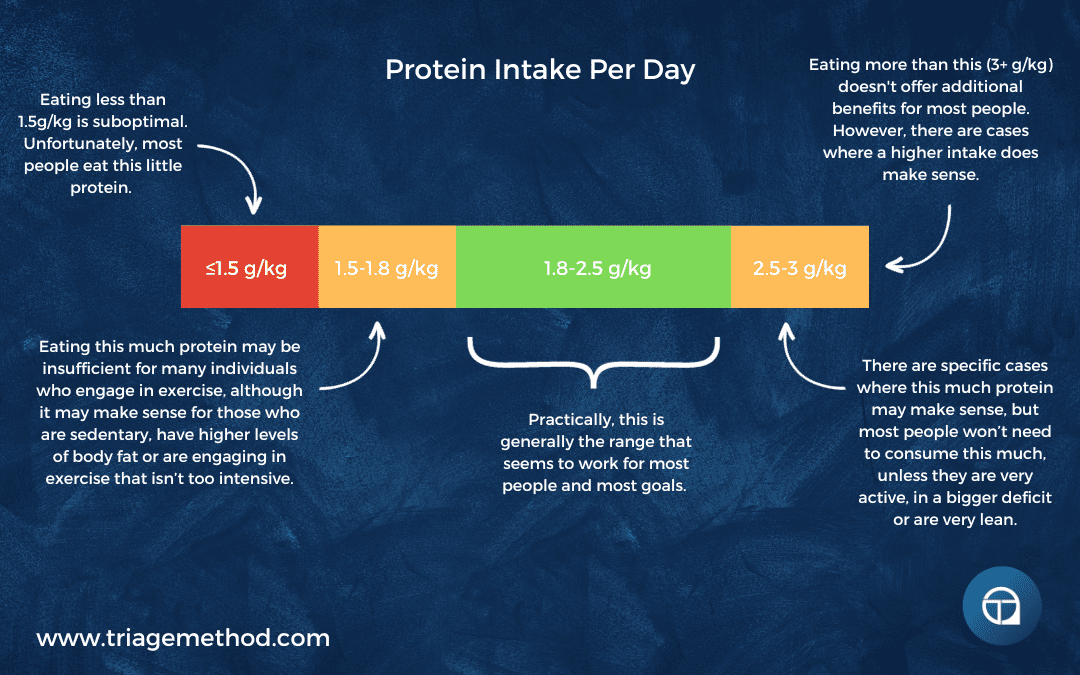

Protein is the most essential macronutrient for muscle repair, growth, and overall body function. It plays a vital role in maintaining lean body mass, improving recovery from exercise, and keeping you full for longer periods. The optimal intake is 1.8-2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight, though highly active individuals or those looking to maximise muscle gain may even benefit from higher intakes (i.e. 2.5g/kg/day).

To maximise muscle protein synthesis, it’s best to spread protein intake across 3-5 meals per day. Each meal should contain at least 20-40 grams of high-quality protein to optimise absorption and utilisation.

Good sources of protein include:

- Animal sources: Chicken, lean beef, turkey, fish (salmon, tuna, cod), eggs, and dairy products like Greek yogurt and cottage cheese.

- Plant-based sources: Lentils, chickpeas, black beans, tofu, tempeh, quinoa, and high-quality plant-based protein powders.

If you want to dig into this more, we recommend reading: How Much Protein Should You Eat?

Fats

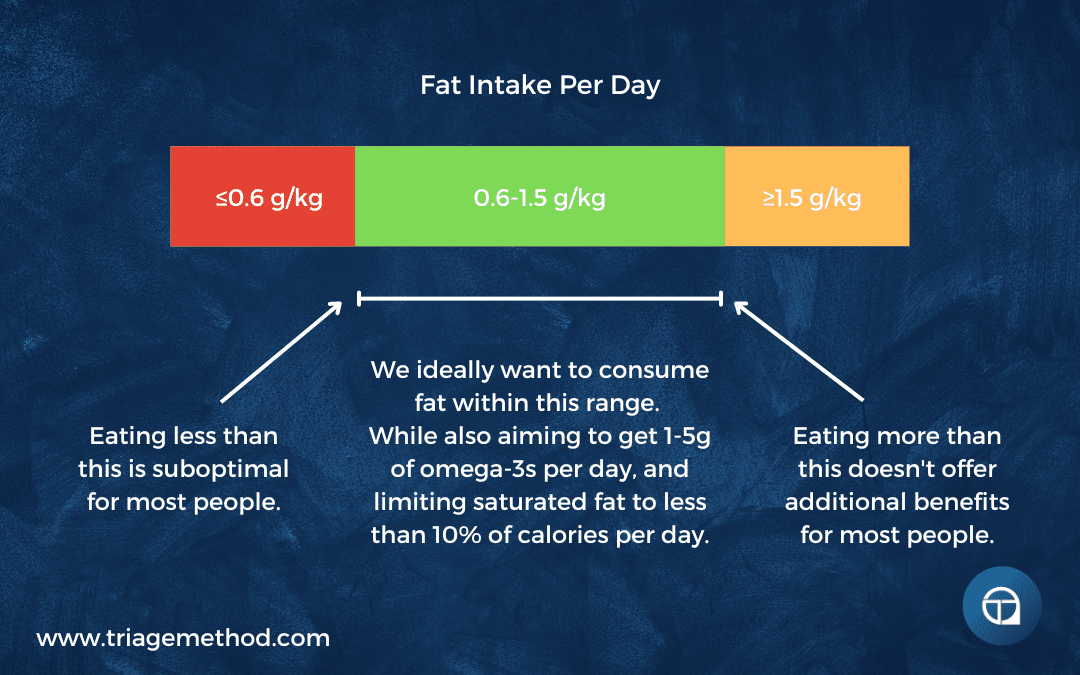

Fats are essential for hormone health, brain function, and overall cellular health. They provide a dense source of energy and play a key role in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Set fat intake at 0.8-1 gram per kilogram of body weight (although, between 0.6-1.5g/kg/day can make sense), ensuring that your diet includes a variety of healthy fats.

It’s crucial to limit saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total calories, and avoid trans fats, which are linked to inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Instead, prioritise heart-healthy fats such as omega-3 fatty acids, which play an important role in reducing inflammation, supporting brain function, and improving heart health.

Aim for 1-3g of omega-3s (EPA/DHA) per day, or 7-21g per week. This can be achieved by consuming fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, or sardines, or by supplementing with high-quality fish oil if necessary.

Good sources of fats include:

- Monounsaturated fats: Olive oil, avocados, nuts (almonds, cashews, pecans), and seeds.

- Polyunsaturated fats: Fatty fish, flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts.

- Saturated fats (in moderation): Dairy, coconut oil, and dark chocolate.

If you want to dig into this more, we recommend reading: How Much Fat Should You Eat?

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates serve as the primary fuel source for the body, particularly for those engaged in exercise. Once protein and fats are accounted for, the remaining calories should come from carbohydrates.

While carb needs vary depending on activity levels, you should prioritise complex, nutrient-dense carbohydrate sources over refined sugars.

Good sources of carbohydrates include:

- Whole grains: Brown rice, quinoa, oats, whole wheat bread, and pasta.

- Legumes: Lentils, beans, chickpeas, and peas.

- Fruits and vegetables: Berries, bananas, potatoes, leafy greens, and cruciferous vegetables.

If you want to dig into this more, we recommend reading: How Much Carbohydrate Should You Eat?

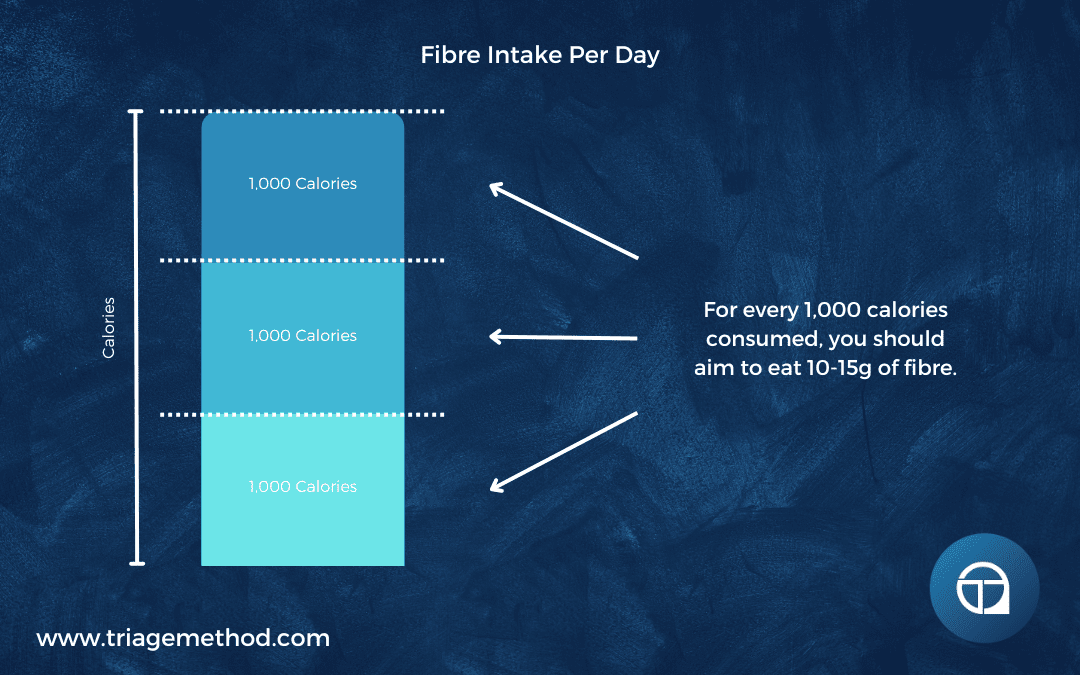

Fibre Intake

Fibre is often overlooked but plays a crucial role in digestive health, blood sugar regulation, and satiety. The recommended intake is 10-15 grams per 1000 calories consumed.

Most people fall short in fibre intake due to a lack of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains in their diets. Instead of relying on fibre supplements, prioritise whole food sources such as:

- Vegetables: Broccoli, carrots, spinach, and kale.

- Fruits: Apples, berries, oranges, and pears.

- Legumes and whole grains: Lentils, quinoa, oats, barley, and whole wheat bread.

If you want to dig into this more, we recommend reading: How Much Fibre Should You Eat?

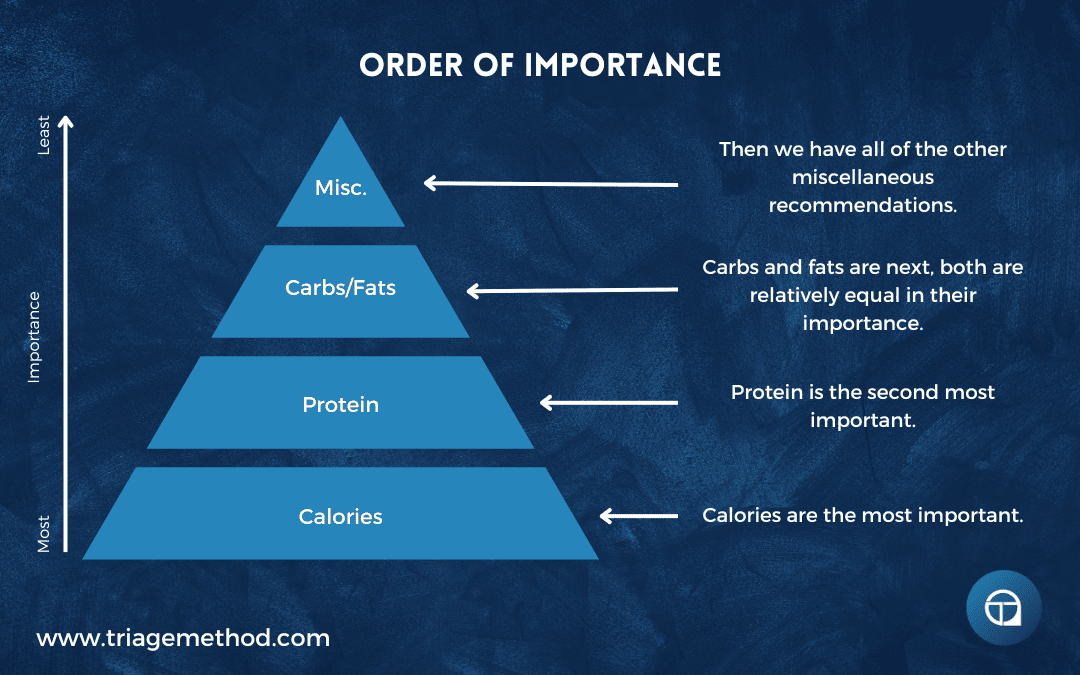

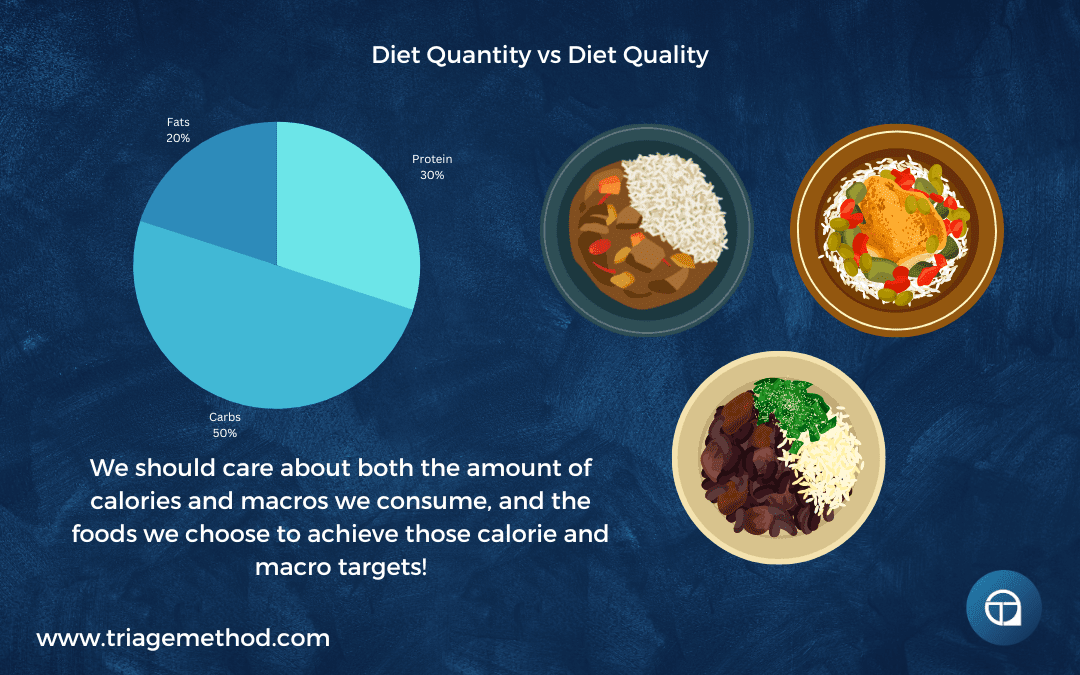

Macronutrients Order of Importance

It is important to keep all of this stuff in context, and thus you need to understand the order of importance when setting your targets.

The most important thing is to hit your calorie target. Then protein is the next most important thing. Carbs and fats are fairly equally important. Then the rest of the recommendations fill in the rest.

If you focus on staying within your calorie goal and hit your protein requirements, you will actually be doing a large portion of what you need to do to actually see improvements in health, body composition and performance.

You can argue that hydration is even more important, as you can survive for a long time without food, but you will die quite quickly without adequate hydration. However, while this is accurate, in the developed world, most people are not likely to suffer from inadequate access to water. As a result, it is just less important to focus your attention on.

Having said that, hydration is very important, so let’s get stuck into that.

Step 3: Hydration

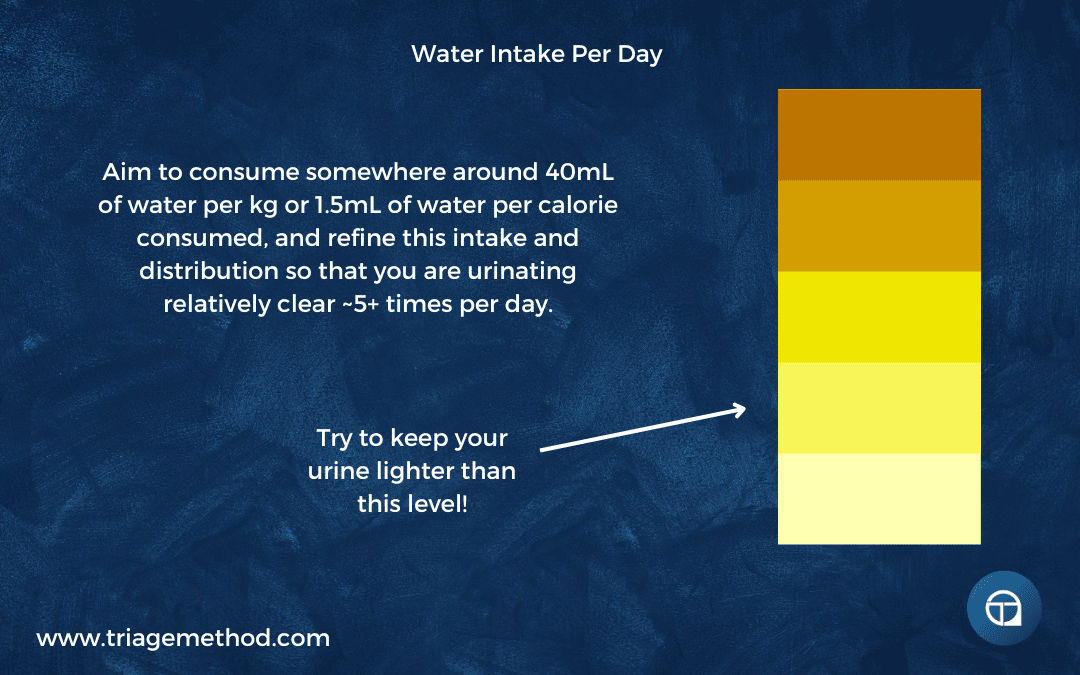

Proper hydration is one of the most overlooked yet essential aspects of a well-balanced diet. Water plays a critical role in nearly every bodily function, including digestion, nutrient transport, temperature regulation, and cognitive performance. Failing to consume adequate water can lead to dehydration, resulting in fatigue, poor concentration, muscle cramps, and impaired physical performance. Conversely, drinking too much water in a short period can lead to electrolyte imbalances, so striking the right balance is crucial.

How Much Water Do You Need?

The general recommendation for water intake is 40mL per kg of body weight, or 1.5mL per calorie consumed. This serves as a strong starting point, but individual hydration needs may vary based on factors such as climate, physical activity levels, and overall dietary composition. Those who live in hot environments or engage in intense exercise will require higher water intake to compensate for increased fluid loss through sweat.

Optimising Water Intake Throughout the Day

Rather than consuming large amounts of water at once, it is best to spread intake evenly throughout the day. A useful guideline is:

- Morning Hydration: Begin your day with a glass of water to rehydrate after sleep.

- Pre-Meal Hydration: Drinking a glass of water 20-30 minutes before meals can aid digestion and prevent overeating.

- During Physical Activity: Drink water consistently before, during and after workouts, especially if sweating heavily.

- Evening Hydration: Reduce intake close to bedtime to avoid disruptions in sleep from frequent urination.

Signs of Proper Hydration

A good indicator of hydration is urine colour. Ideally, urine should be a light, pale yellow. Clear urine can indicate overhydration, while dark yellow or amber urine suggests dehydration. Other signs of proper hydration include:

- Urinating at least 5-7 times per day.

- Experiencing minimal thirst throughout the day.

- Maintaining steady energy levels without symptoms of dehydration, such as headaches or dry skin/lips.

Hydration and Electrolyte Balance

Water alone is not always sufficient for hydration, especially for those engaging in prolonged exercise or spending time in hot conditions. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium play a crucial role in maintaining fluid balance and preventing dehydration-related symptoms such as headaches and dizziness.

Consuming electrolyte-rich foods like bananas, leafy greens, nuts, and seeds, or supplementing with electrolyte drinks when necessary, can enhance hydration status.

Common Hydration Mistakes

- Drinking Only When Thirsty: Thirst is a late indicator of dehydration; aim to sip water consistently instead of waiting until you feel thirsty.

- Overhydration Without Electrolytes: Consuming excessive water without replenishing electrolytes can lead to hyponatremia, a condition where sodium levels become dangerously low.

- Ignoring Hydration in Cold Weather: Many assume hydration is only crucial in the heat, but cold environments can also lead to dehydration, particularly if wearing heavy clothing that induces sweating.

By maintaining steady hydration levels, ensuring proper electrolyte balance, and adjusting water intake based on personal needs, you can optimise overall health, digestion, and athletic performance while preventing dehydration-related issues.

If you want to dig into this more, we recommend reading: How Much Water Should You Drink?

Step 4: Food Variety and Micronutrients

Ensuring a diverse and nutrient-rich diet is essential for overall health, optimal performance, and long-term sustainability. Many people fall into the trap of eating the same foods repeatedly, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies, food boredom, and suboptimal gut health.

By incorporating a wide range of foods, you not only increase your intake of essential vitamins and minerals but also improve your body’s ability to absorb and utilise these nutrients effectively.

Eat the Rainbow

One of the best ways to ensure adequate micronutrient intake is by consuming a variety of colourful fruits and vegetables. Different colours in plant-based foods often indicate the presence of specific phytonutrients, antioxidants, and vitamins that serve critical functions in the body.

- Red foods (tomatoes, red bell peppers, strawberries, cherries) contain lycopene, which is linked to heart health and reduced cancer risk.

- Orange and yellow foods (carrots, sweet potatoes, oranges, mangoes) are rich in beta-carotene, essential for vision and immune function.

- Green foods (spinach, kale, broccoli, Brussels sprouts) provide chlorophyll, folate, and vitamin K, which support blood clotting, bone health, and detoxification.

- Blue and purple foods (blueberries, blackberries, eggplant, purple cabbage) contain anthocyanins, which have powerful anti-inflammatory and cognitive benefits.

- White and brown foods (mushrooms, garlic, onions, cauliflower) provide prebiotics and allicin, which support gut health and immune function.

By making a conscious effort to eat a colourful plate, you naturally improve your micronutrient intake and overall diet quality.

Rotate Protein, Carbohydrate, and Fat Sources

Dietary monotony not only increases the risk of nutrient deficiencies but can also lead to food intolerances and gut microbiome imbalances. Instead of relying on the same protein, carb, and fat sources every day, aim for variety to maximise nutrient diversity and digestion efficiency.

- Protein Rotation: Instead of eating only chicken and eggs, include a mix of plant and animal sources such as fish, lean red meat, tofu, tempeh, legumes, cottage cheese, and lentils.

- Carbohydrate Rotation: Move beyond traditional grains like rice and wheat; incorporate quinoa, barley, oats, bulgur, potatoes, and legumes.

- Fat Rotation: Balance fat intake by including different sources like avocados, nuts, seeds, olive oil, fatty fish, and dairy.

This rotation helps you cover a broader range of essential nutrients while making your meals more enjoyable and sustainable.

Nutrient-Dense Choices Over Processed Options

Whole, unprocessed foods should make up the majority of your diet. While occasional indulgence in processed foods is perfectly fine, regularly prioritising nutrient-dense choices leads to better energy levels, digestion, and long-term health.

- Choose whole grains over refined grains (brown rice instead of white rice, whole wheat over white bread).

- Opt for natural sources of sugar like fruits, rather than added sugars found in processed snacks.

- Pick minimally processed protein sources such as fresh meats, eggs, and legumes over processed meats like hot dogs or packaged deli slices.

- Go for fresh, whole foods instead of heavily processed convenience items with long ingredient lists.

By focusing on nutrient density, you ensure that every calorie you consume is contributing to your body’s overall well-being, rather than just providing empty energy.

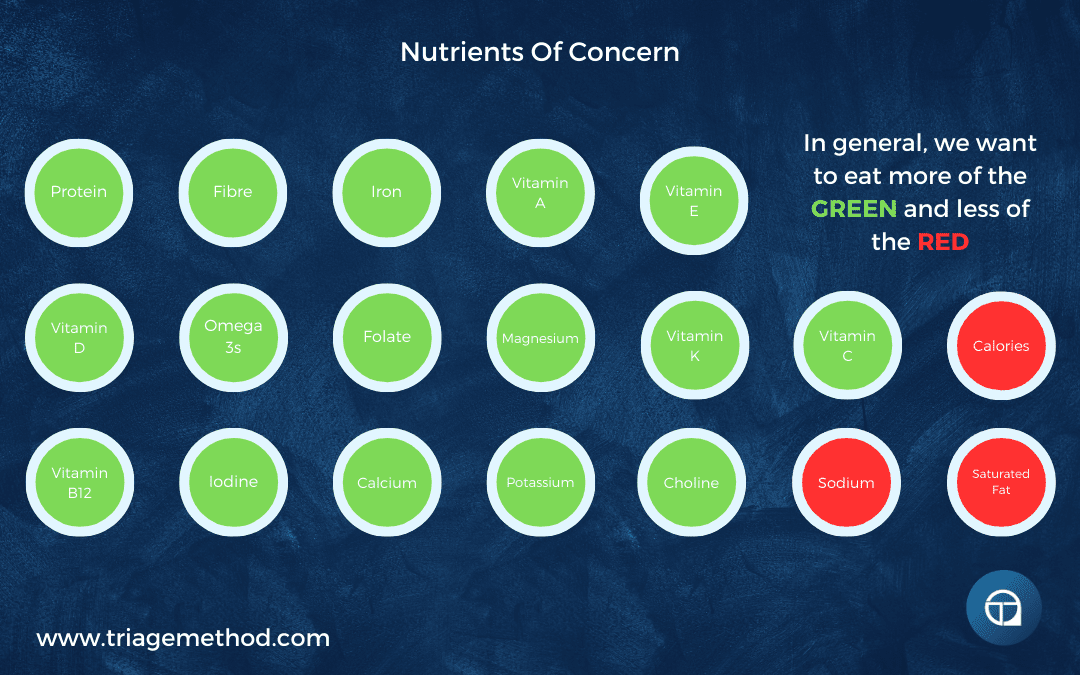

Balancing Micronutrient Intake

While macronutrients (proteins, carbs, and fats) get the most attention, micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are just as crucial for optimal functioning. Deficiencies in key micronutrients can lead to fatigue, weakened immunity, and chronic health issues. Some of the most essential micronutrients to focus on include:

- Iron: Found in red meat, spinach, lentils, and fortified cereals; important for oxygen transport and energy levels.

- Calcium: Critical for bone health, found in dairy, leafy greens, and fortified plant milk.

- Magnesium: Supports muscle function, relaxation, and heart health; abundant in nuts, seeds, and whole grains.

- Zinc: Vital for immune function and wound healing; present in shellfish, meat, and legumes.

- B Vitamins: Essential for energy production and brain function; available in whole grains, eggs, and dairy.

- Vitamin C: Helps with immunity and collagen production; best sources are citrus fruits, bell peppers, and berries.

A well-balanced diet that includes a variety of whole foods will typically provide all the necessary micronutrients, but those with restrictive diets (e.g., vegan, vegetarian, or keto) may need to pay closer attention to ensure they meet their needs.

There are a number of nutrients of concern, that many individuals consume low amounts of. So ensuring your diet at least contains adequate amounts of these nutrients makes sense.

A Holistic Approach to Food Variety & Micronutrient Intake

Incorporating variety into your diet not only enhances your overall health but also makes your meals more enjoyable. By eating a diverse range of colourful foods, rotating macronutrient sources, and prioritising whole, nutrient-dense choices, you ensure a well-rounded intake of essential vitamins and minerals. This holistic approach not only improves immediate health outcomes but also sets the foundation for long-term health.

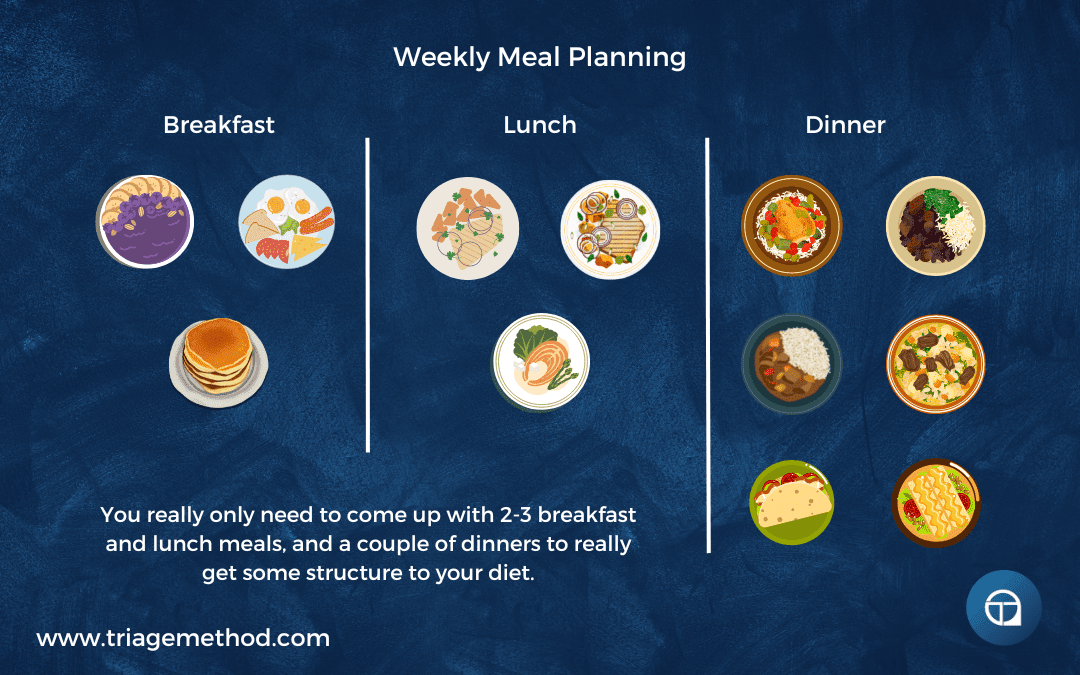

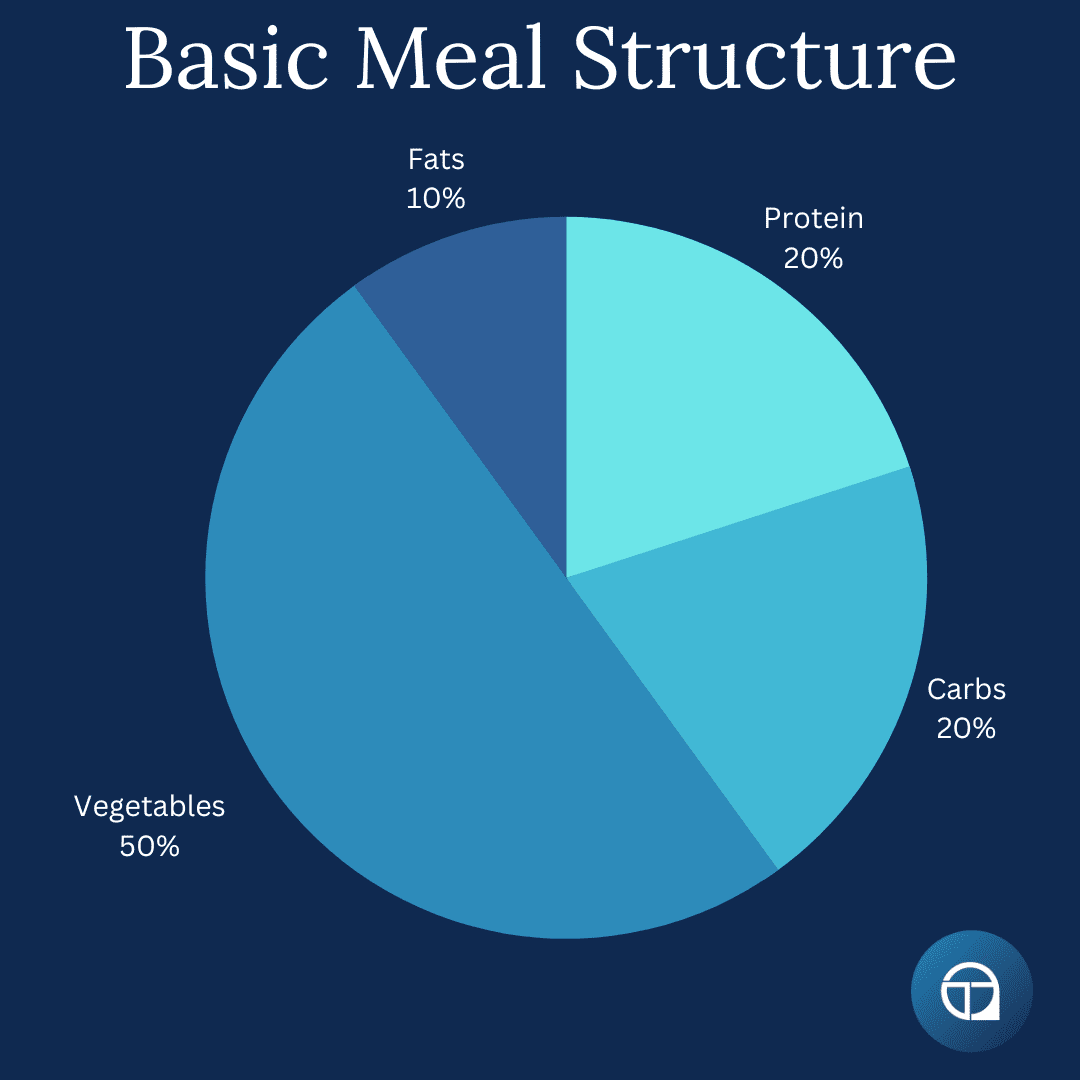

Step 5: Structuring Your Meals: Meal Timing & Distribution

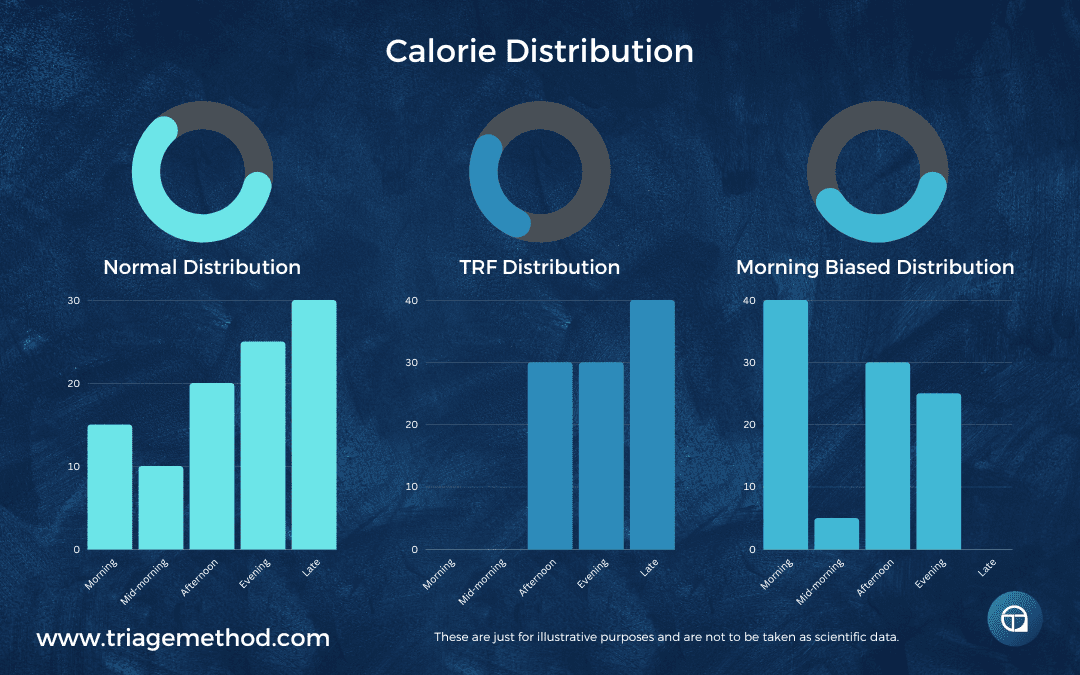

One of the most overlooked aspects of a well-structured diet is how meals are spaced throughout the day. While total calorie and macronutrient intake are the most important factors, meal timing can influence energy levels, digestion, and overall adherence to your nutrition plan.

For most people, having the majority of your meals look roughly like this generic meal structure, and spreading them across the day in a balanced manner works best. The body functions more efficiently when it is consistently fueled rather than subjected to extreme fluctuations in intake.

A good rule of thumb is to eat every 3-5 hours, ensuring that meals provide steady energy and prevent excessive hunger, which can lead to overeating later.

In addition to spacing meals, avoiding excessively large meals close to bedtime is generally recommended. Ideally, you should allow at least 2-3 hours between your last meal and going to sleep. This allows time for digestion and may improve sleep quality by preventing discomfort or acid reflux.

Another important concept is front-loading calories, meaning you consume a larger portion of your daily intake earlier in the day. Studies suggest that eating more in the morning and afternoon can enhance metabolic health, stabilise blood sugar levels, and improve appetite regulation throughout the day.

While this doesn’t mean you should force-feed yourself breakfast if you’re not hungry, making sure you aren’t saving the bulk of your calories for late evening is generally beneficial.

However, personal preferences and individual routines also play a role in meal structuring. Some people function better with a more structured meal pattern, while others prefer flexibility. The key takeaway is that meal distribution should support sustained energy, digestion, and satiety, rather than leaving you with extended periods of hunger followed by excessive calorie consumption.

Step 6: Adjusting Calories Based on Goals

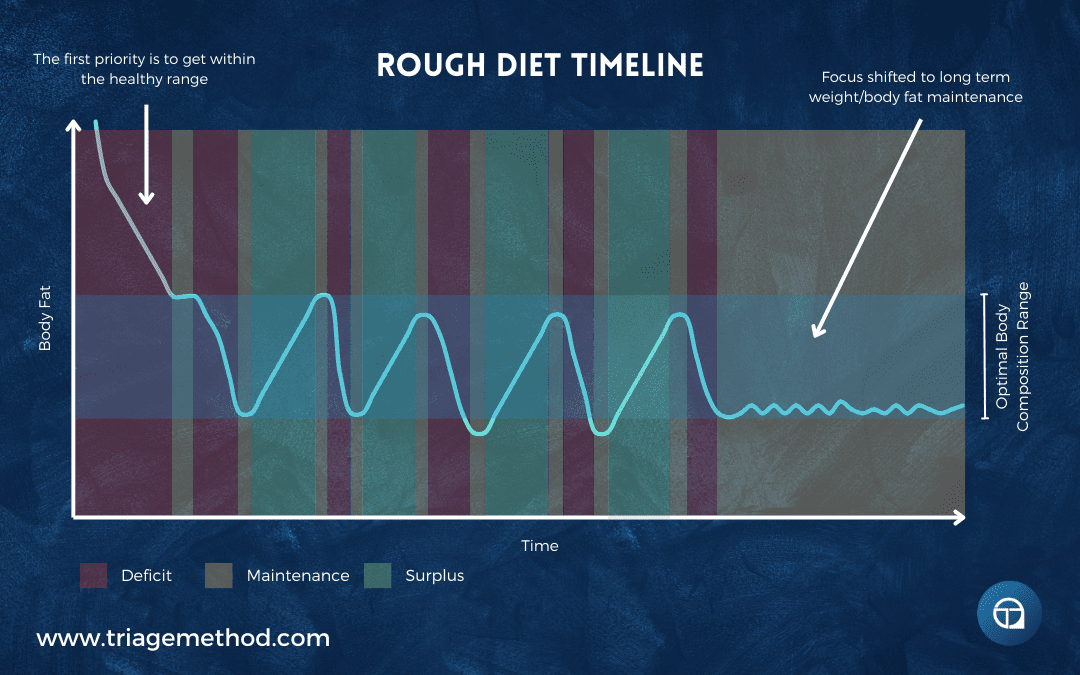

Once you have identified your maintenance calories, you have been eating at that for ~2 weeks, you have structured your diet correctly and you are confident in your abilities to eat at that level consistently, you can then make strategic adjustments based on your specific goals.

Whether your focus is fat loss, muscle gain, or body recomposition, you want to set up your diet in a way that ensures sustainable progress. Nobody wants to fall into yo-yo dieting, and it can be avoided by simply setting your diet up correctly.

Fat Loss

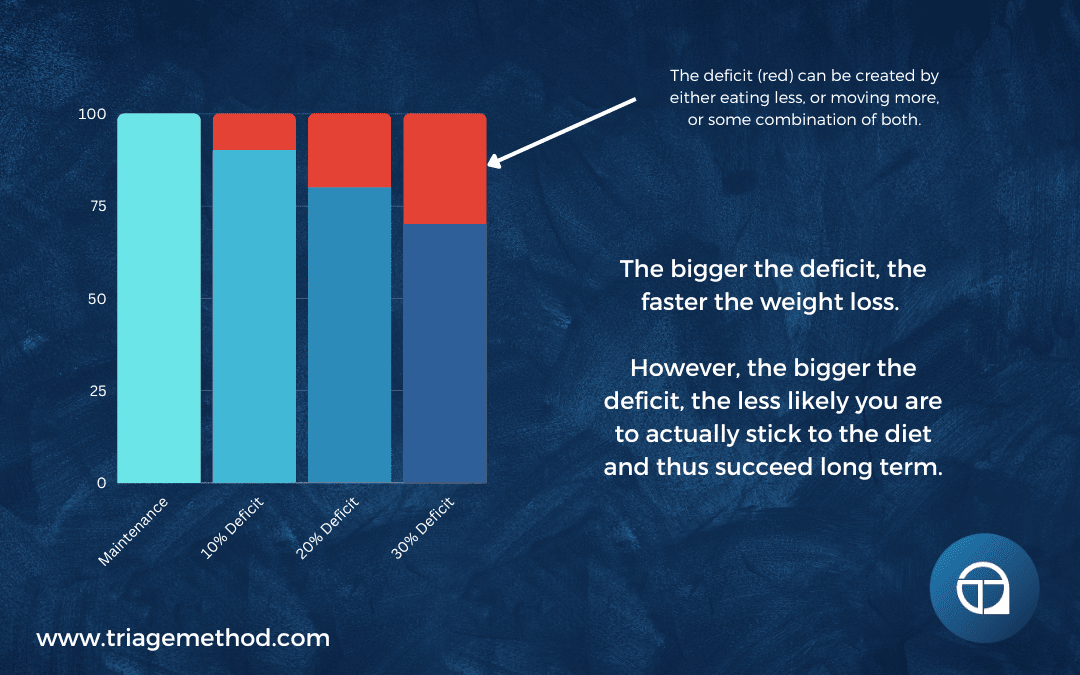

If your goal is to lose fat, you need to create a caloric deficit, meaning you must consume fewer calories than you burn. A reasonable starting point is reducing your intake by 200-300 calories per day.

Many individuals attempt aggressive calorie reductions, thinking they will achieve faster results. However, extreme deficits can lead to metabolic adaptations, excessive hunger, muscle loss, and an increased likelihood of binge eating.

A sustainable fat loss rate is 0.5 to 1% body weight loss per week, depending on your starting weight and activity level.

You will want to monitor weight trends over 2-4 weeks, rather than daily fluctuations, to assess if your calorie deficit is actually effective. If fat loss stalls for more than two weeks, consider adjusting your intake by another 100-200 calories or increasing physical activity through strength training, low-intensity cardio and/or increasing your daily step count.

Muscle Gain

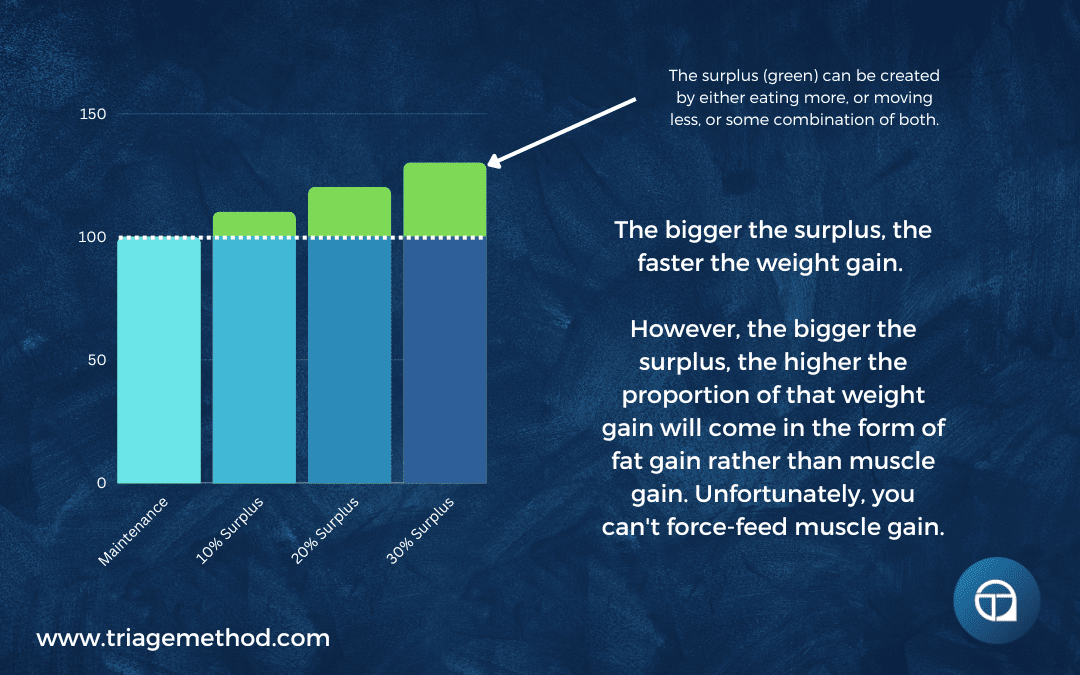

For those focused on muscle building, a caloric surplus is necessary to support growth. However, excessive calorie intake can lead to unnecessary fat gain. The goal should be a slow and lean bulk, where you increase 200-300 calories per day and track progress over several weeks.

A sustainable muscle gain rate is approximately 0.125 to 0.25 kg per week (or 0.5-1kg per month) (and maybe half of this if you are a woman or a more advanced trainee).

If your weight gain exceeds 0.25 kg per week, it may indicate excessive fat accumulation. In such cases, scale back your surplus slightly to maintain a leaner bulk. When you first start eating in a surplus, there may be a week or two where your weight gain is more rapid. This is mostly due to extra food in your digestive system, and extra stored glycogen and water. So you can really only assess whether things are set up correctly after ~2 weeks of eating in a surplus.

If you are gaining much faster than this, you may need to eat slightly less food, and if you are gaining much less than this, you may need to eat slightly more (try adding 100-200 calories more).

Body Recomposition (Fat Loss + Muscle Gain)

For individuals who want to lose fat while simultaneously gaining muscle, the best approach is to keep calories around maintenance while focusing on high protein intake and progressive resistance training. This process, known as body recomposition, is especially effective for beginners, overweight individuals, and those returning from a long break, but it is a very slow process.

For most people, rather than trying to accomplish body recomposition, they should instead go through periods of dieting down and then gaining. Trying to do both at once is just very difficult.

Adjusting Calories Over Time

No matter what your goal is, avoid making frequent changes to your calorie intake. The body takes time to adapt, and weight fluctuations are normal. Instead of reacting to daily weight changes, track your progress over at least two weeks before considering adjustments.

If progress stalls, make small adjustments:

- For fat loss: Reduce calorie intake by an additional 100-200 calories per day or slightly increase physical activity.

- For muscle gain: Increase calories by another 100-200 calories per day if weight gain is too slow.

- For recomposition: Focus on improving training intensity and nutrient timing rather than adjusting calories too frequently.

By taking a structured and patient approach to calorie adjustments, you ensure sustainable results without unnecessary metabolic disruptions. This method not only makes progress predictable but also helps maintain overall well-being and energy levels throughout your fitness journey.

Your metabolism will adapt over time, especially as you lose or gain weight. So you will have to make adjustments, but these adjustments should be infrequent and small. You should not be making adjustments every single week, and you should especially not be making large adjustments every week.

Step 7: Individual Adjustments

While these guidelines provide a solid foundation for nutrition, it’s crucial to understand that no single approach works for everyone. Your diet should be tailored to your unique needs, taking into account your lifestyle, personal preferences, physical activity levels, and even genetic predispositions.

Nutrition is not just about hitting macro and calorie targets, it’s about creating a dietary system that you can maintain over the long term while ensuring optimal health and performance.

Personal Preferences and Dietary Adherence

One of the most important aspects of dietary success is adherence. If your diet is not enjoyable, sustainable, or practical in your daily life, you are unlikely to stick with it. This is why rigid meal plans often fail. They do not consider individual food preferences, social habits, or cultural factors.

Instead of forcing yourself to eat foods you dislike, find nutrient-dense options that you enjoy. For example, if you dislike chicken breast but love fish, prioritise fish as a primary protein source. If rice doesn’t sit well with you but potatoes do, make that your go-to carb source.

Training Demands and Activity Level Adjustments

If you engage in high-intensity training or endurance sports, your caloric and macronutrient needs will be significantly different from someone who is sedentary. Athletes and those who train frequently will likely require:

- Higher carbohydrate intake to support glycogen replenishment and recovery.

- Increased protein intake to aid in muscle repair and minimise breakdown.

- Greater electrolyte and hydration management to support performance and prevent dehydration-related fatigue.

On the other hand, individuals with a more sedentary lifestyle may need to monitor carbohydrate intake more closely to avoid excessive caloric consumption.

There is no one-size-fits-all with this stuff.

Adjusting for Medical Conditions and Digestive Health

Those with specific medical conditions or dietary sensitivities will also need to adjust their nutrition accordingly. For example:

- Diabetics may need to prioritise slow-digesting, fibre-rich carbohydrates to maintain stable blood sugar levels.

- Individuals with IBS or food intolerances may need to limit specific foods that trigger digestive distress. Listening to your body is critical, if certain foods consistently cause discomfort, bloating, or sluggishness, consider eliminating or substituting them with better alternatives.

- Those with cardiovascular concerns may need to focus more on heart-healthy fats and fibre intake to support cholesterol and blood pressure management.

You have to set your diet up in a way that actually makes sense for your unique conditions and needs.

Tracking Progress and Making Data-Driven Adjustments

Rather than making drastic changes based on short-term fluctuations in weight or energy, track trends over weeks and months. Monitor:

- Weight and body composition changes

- Performance in workouts and daily energy levels

- Hunger, satiety, and digestion

- Overall well-being and mental clarity

If something isn’t working, make small, gradual adjustments.

For example, if you are not recovering well from workouts, consider increasing calories, and protein intake (while also paying attention to sleep quality and stress management).

Alternatively, if you notice you are always feeling hungry 2 hours after your morning meal, then making a small adjustment to how you distribute your calories across the day may make sense. Or perhaps you need to eat more protein, fats and/or fibre at breakfast to slow digestion and provide a more steady supply of energy.

The key is to make small changes, and then be patient and allow enough time for changes to take effect before making further modifications.

Sustainability Over Perfection

It is important to remember that perfection is not the goal with all of this nutrition stuff. Consistency is.

A diet that is 80-90% aligned with whole, nutrient-dense foods while allowing for some flexibility is far more sustainable than an ultra-restrictive plan that leads to burnout.

Understanding your body’s needs, adjusting based on real-world feedback, and making informed changes over time will ensure you create a dietary strategy that is both effective and enjoyable in the long run.

How To Set Up Your Diet Review

We have covered a lot so far, and while we certainly didn’t cover every single possible nuance, you hopefully now have a good general idea about how to set up a successful diet. I know a few of you just wanted the quick summary of what to do, and you have skipped the rest of the article so far, so here you go, here is a quick summary.

The general guidelines can be summed up as follows:

- Calories are determined based on your current intake and how your body weight is changing with respect to that. The process is simple enough, track your current intake every day for a week or two using a calorie tracking app such as myfitnesspal. Assess how your weight has changed across that week or two, and that will tell you if you are in a surplus, maintenance or a deficit (if you lose weight you are in a deficit, if you gain weight you are in a surplus, and if your weight stays the same, you are at maintenance). You could use a calorie calculator, but this is just a best guess, and you will still have to use real-world feedback. You must be accurate with tracking your intake over at least a week, as what you eat on a single day is less important than the average over time. Some people eat very little Monday to Friday and then eat an enormous amount on the weekends, which means their daily average intake is much higher than they think. This is one of the most common things we see, and this is why it is important to be accurate in your assessment of your current intake across at least a week (and ideally 2 weeks).

- Set your calories in and around maintenance, focus on dialling in good food habits and getting your macronutrient intake and general meal structure where it should be, and see how your body responds to eating that way for ~2 weeks. If you want to lose weight, reduce calories by a small amount (200-300 calories), if you want to gain weight, increase calories by a small amount (200-300 calories) and only adjust your calories when you have stalled for more than 2 weeks.

- Most people will do best if they fairly evenly distribute their calories across the day, rather than eating large amounts at any singular time or going for long periods of time without food. Most people would be best served by leaving a 2-3 hour gap between their last meal and bedtime, and you could make a strong argument for biasing more of your calorie intake to the earlier portion of the day.

- Protein should be set at 1.8 to 2.2 grams per kilogram body weight, for most people, for most goals. While you can get away with less, there are no downsides (physiologically, and assuming you have no illness that would be affected negatively by increased protein intake) and only benefits from getting your protein into the 1.8 to 2.2g/kg range. Ideally, we would like to see this spread across 3-5 meals per day.

- Fats should be set as 0.8-1 grams per kilogram body weight. Most people would do best to reduce their saturated fat intake to less than 10% of their calories, while also aiming to get at least 1-3g of the omega-3s (EPA and DHA) per day, or 7-21g across the week (as fats can be stored in the body).

- Carbohydrates should be set as the amount the remaining calories allow for. Ideally, you would choose carb sources that are less refined, and offer more nutrients to the diet than just carbohydrates.

- Fibre should be 10-15 grams per 1000 calories. This is usually an area that people fall down on, as they don’t eat enough vegetables. Getting sufficient fibre, without the use of supplements is usually a good sign that food selection practices (i.e. eating enough fruit and vegetables) are in a good place.

- Eat the rainbow and vary your food selection. Food isn’t supposed to be boring. Eat a variety of different foods each week, alternating your protein, carb, fat and fibre sources.

- Water should be consumed at roughly 40mL per kg or 1.5mL of water per calorie eaten, spread relatively evenly throughout the day. You should then refine this intake and distribution so that you are urinating relatively clear ~5+ times per day.

- You should make adjustments that account for you as an individual, while paying respect to the overall guidelines. The guidelines are just a very rough starting point. They certainly aren’t the be-all and end-all, and they will likely need to be modified for you and your life situation, but they do serve as a good general baseline. There is a lot of nuance to the guidelines, and good rationales for doing something slightly different. However, if you are doing something completely counter to these guidelines, you really should have a very clear rationale and explanation for that.

If you can follow those guidelines, you will be doing a pretty damn good job with the diet!

If all of this was too much for you and you just want a simplified version, you may enjoy our Ultimate Diet Set Up Calculator.

And that is it! If you enjoyed this articleseries, or you found it particularly helpful, then consider subscribing to our newsletter to stay up to date with all the new articles we create. We also frequently post shorter more “to the point” tips on social media, so consider following us on Instagram and YouTube!

You can read through any of the articles in this series by clicking the relevant link below:

- Why Nutrition Is Important

- The Goals Of Nutrition

- Types Of Diets

- How Many Calories Should You Eat?

- How Much Protein Should You Eat?

- How Much Fat Should You Eat?

- How Much Carbohydrate Should You Eat?

- How Much Fibre Should You Eat?

- How Much Water Should You Drink?

- Dealing With Alcohol In The Diet

- Overview of Diet Quantity

- Understanding Diet Quality

- Putting Healthy Eating Guidelines Into Practice

- Understanding Food Selection

- Diet Quality: Micronutrients and Nutrients Of Concern

- Diet Quality Overview

- Longer Term Diet Planning

References and Further Reading

Fell, D. A., & Thomas, S. (1995). Physiological control of metabolic flux: the requirement for multisite modulation. Biochemical Journal, 311(1), 35–39. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj3110035

Levine, J. A. (2002). Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 16(4), 679–702. http://doi.org/10.1053/beem.2002.0227

Ballesteros, F. J., Martinez, V. J., Luque, B., Lacasa, L., Valor, E., & Moya, A. (2018). On the thermodynamic origin of metabolic scaling. Scientific Reports, 8(1). http://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19853-6

Manini, T. M. (2010). Energy expenditure and ageing. Ageing Research Reviews, 9(1), 1–11. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2009.08.002

Mcmurray, R. G., Soares, J., Caspersen, C. J., & Mccurdy, T. (2014). Examining Variations of Resting Metabolic Rate of Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(7), 1352–1358. http://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000232

Stiegler, P., & Cunliffe, A. (2006). The Role of Diet and Exercise for the Maintenance of Fat-Free Mass and Resting Metabolic Rate During Weight Loss. Sports Medicine, 36(3), 239–262. http://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636030-00005

Curtis, V., Henry, C. J. K., Birch, E., & Ghusain-Choueiri, A. (1996). Intraindividual variation in the basal metabolic rate of women: Effect of the menstrual cycle. American Journal of Human Biology, 8(5), 631–639. http://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6300(1996)8:5<631::aid-ajhb8>3.0.co;2-y

Harris, J. A., & Benedict, F. G. (1918). A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 4(12), 370–373. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.4.12.370

Roza, A. M., & Shizgal, H. M. (1984). The Harris-Benedict equation reevaluated: resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 40(1), 168–182. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/40.1.168

Mifflin, M. D., Jeor, S. T. S., Hill, L. A., Scott, B. J., Daugherty, S. A., & Koh, Y. O. (1990). A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 51(2), 241–247. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241

Frankenfield, D., Roth-Yousey, L., & Compher, C. (2005). Comparison of Predictive Equations for Resting Metabolic Rate in Healthy Nonobese and Obese Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(5), 775–789. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.005

Johnstone, A. M., Murison, S. D., Duncan, J. S., Rance, K. A., & Speakman, J. R. (2005). Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(5), 941–948. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.5.941

Speakman, J. R., Król, E., & Johnson, M. S. (2004). The Functional Significance of Individual Variation in Basal Metabolic Rate. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 77(6), 900–915. http://doi.org/10.1086/427059

Smith, D. A., Dollman, J., Withers, R. T., Brinkman, M., Keeves, J. P., & Clark, D. G. (1997). Relationship between maximum aerobic power and resting metabolic rate in young adult women. Journal of Applied Physiology, 82(1), 156–163. http://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.156

Ravussin, E., Lillioja, S., Anderson, T. E., Christin, L., & Bogardus, C. (1986). Determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure in man. Methods and results using a respiratory chamber. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 78(6), 1568–1578. http://doi.org/10.1172/jci112749

Wolfe, R. R. (2006). The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 84(3), 475–482. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.3.475

Wang, Z., Heshka, S., Zhang, K., Boozer, C. N., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2001). Resting Energy Expenditure: Systematic Organization and Critique of Prediction Methods*. Obesity, 9(5), 331–336. http://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2001.42

Mcpherron, A. C., Guo, T., Bond, N. D., & Gavrilova, O. (2013). Increasing muscle mass to improve metabolism. Adipocyte, 2(2), 92–98. http://doi.org/10.4161/adip.22500

Levine, J. A., Weg, M. W. V., Hill, J. O., & Klesges, R. C. (2006). Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 26(4), 729–736. http://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.0000205848.83210.73 http://www.fao.org/3/m2845e/m2845e00.htm

Martin, C. K., Heilbronn, L. K., Jonge, L. D., Delany, J. P., Volaufova, J., Anton, S. D., … Ravussin, E. (2007). Effect of Calorie Restriction on Resting Metabolic Rate and Spontaneous Physical Activity**. Obesity, 15(12), 2964–2973. http://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.354

Redman, L. M., Heilbronn, L. K., Martin, C. K., Jonge, L. D., Williamson, D. A., Delany, J. P., & Ravussin, E. (2009). Metabolic and Behavioral Compensations in Response to Caloric Restriction: Implications for the Maintenance of Weight Loss. PLoS ONE, 4(2). http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004377

Martin, C. K., Das, S. K., Lindblad, L., Racette, S. B., Mccrory, M. A., Weiss, E. P., … Kraus, W. E. (2011). Effect of calorie restriction on the free-living physical activity levels of nonobese humans: results of three randomized trials. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(4), 956–963. http://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00846.2009

Stiegler, P., & Cunliffe, A. (2006). The Role of Diet and Exercise for the Maintenance of Fat-Free Mass and Resting Metabolic Rate During Weight Loss. Sports Medicine, 36(3), 239–262. http://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636030-00005

Goran, M. I. (2005). Estimating energy requirements: regression based prediction equations or multiples of resting metabolic rate. Public Health Nutrition, 8(7a), 1184–1186. http://doi.org/10.1079/phn2005803

Johannsen, D. L., Knuth, N. D., Huizenga, R., Rood, J. C., Ravussin, E., & Hall, K. D. (2012). Metabolic Slowing with Massive Weight Loss despite Preservation of Fat-Free Mass. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 97(7), 2489–2496. http://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1444

Clamp, L., Hume, D., Lambert, E., & Kroff, J. (2018). Successful and unsuccessful weight-loss maintainers: Strategies to counteract metabolic compensation following weight loss. Journal of Nutritional Science, 7, E20. doi:10.1017/jns.2018.11 https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2018.11

Hall, K. D. (2018). The complicated relation between resting energy expenditure and maintenance of lost weight. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 108(4), 652–653. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy259

Ostendorf, D. M., Melanson, E. L., Caldwell, A. E., Creasy, S. A., Pan, Z., MacLean, P. S., Wyatt, H. R., Hill, J. O., & Catenacci, V. A. (2018). No consistent evidence of a disproportionately low resting energy expenditure in long-term successful weight-loss maintainers. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 108(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy179

Heilbronn, L. K., Jonge, L. D., Frisard, M. I., Delany, J. P., Larson-Meyer, D. E., Rood, J., … Team, F. T. P. C. (2006). Effect of 6-Month Calorie Restriction on Biomarkers of Longevity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Oxidative Stress in Overweight Individuals. Jama, 295(13), 1539. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.13.1539

Zurlo, F., Trevisan, C., Vitturi, N., Ravussin, E., Salvò, C., Carraro, S., … Avogaro, A. (2019). One-year caloric restriction and 12-week exercise training intervention in obese adults with type 2 diabetes: emphasis on metabolic control and resting metabolic rate. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 42(12), 1497–1507. http://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-019-01090-x

Gilliat-Wimberly, M., Manore, M. M., Woolf, K., Swan, P. D., & Carroll, S. S. (2001). Effects of Habitual Physical Activity on the Resting Metabolic Rates and Body Compositions of Women Aged 35 to 50 Years. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 101(10), 1181–1188. http://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8223(01)00289-9

Pontzer H, Durazo-Arvizu R, Dugas LR, et al. Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans. Curr Biol. 2016;26(3):410-417. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.046 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4803033/

Pontzer H. Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and the Evolutionary Biology of Energy Balance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2015;43(3):110-116. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000048 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25906426/

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad–Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):491-497. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24620037/

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, et al, IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:687-697. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/11/687

Weigle DS, Duell PB, Connor WE, Steiner RA, Soules MR, Kuijper JL. Effect of fasting, refeeding, and dietary fat restriction on plasma leptin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(2):561-565. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.2.3757 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9024254/

Jørgensen JO, Vahl N, Dall R, Christiansen JS. Resting metabolic rate in healthy adults: relation to growth hormone status and leptin levels. Metabolism. 1998;47(9):1134-1139. doi:10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90289-x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9751244/

Jeon JY, Steadward RD, Wheeler GD, Bell G, McCargar L, Harber V. Intact sympathetic nervous system is required for leptin effects on resting metabolic rate in people with spinal cord injury. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(1):402-407. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-020939 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12519883/

Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD. Leptin responses to overfeeding: relationship with body fat and nonexercise activity thermogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(8):2751-2754. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.8.5910 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10443673/

Roberts SB, Nicholson M, Staten M, et al. Relationship between circulating leptin and energy expenditure in adult men and women aged 18 years to 81 years. Obes Res. 1997;5(5):459-463. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00671.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9385622/

Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(1):21-34. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17212793/

Sinha MK, Opentanova I, Ohannesian JP, et al. Evidence of free and bound leptin in human circulation. Studies in lean and obese subjects and during short-term fasting. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(6):1277-1282. doi:10.1172/JCI118913 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC507552/

Lammert O, Grunnet N, Faber P, et al. Effects of isoenergetic overfeeding of either carbohydrate or fat in young men. Br J Nutr. 2000;84(2):233-245. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11029975/

Horton TJ, Drougas H, Brachey A, Reed GW, Peters JC, Hill JO. Fat and carbohydrate overfeeding in humans: different effects on energy storage. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62(1):19-29. doi:10.1093/ajcn/62.1.19 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7598063/

Havel PJ, Townsend R, Chaump L, Teff K. High-fat meals reduce 24-h circulating leptin concentrations in women. Diabetes. 1999;48(2):334-341. doi:10.2337/diabetes.48.2.334 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10334310/

Romon M, Lebel P, Velly C, Marecaux N, Fruchart JC, Dallongeville J. Leptin response to carbohydrate or fat meal and association with subsequent satiety and energy intake. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(5):E855-E861. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.5.E855 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10567012/

Kolaczynski JW, Nyce MR, Considine RV, et al. Acute and chronic effects of insulin on leptin production in humans: Studies in vivo and in vitro. Diabetes. 1996;45(5):699-701. doi:10.2337/diab.45.5.699 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8621027/

Spiegel K, Leproult R, L’hermite-Balériaux M, Copinschi G, Penev PD, Van Cauter E. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(11):5762-5771. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15531540/

Zarogoulidis, P., Lampaki, S., Turner, J. F., Huang, H., Kakolyris, S., Syrigos, K., & Zarogoulidis, K. (2014). mTOR pathway: A current, up-to-date mini-review (Review). Oncology Letters, 8(6), 2367–2370. http://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2608

Liu, G. Y., & Sabatini, D. M. (2020). mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 21(4), 183–203. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y

Lipton, J. O., & Sahin, M. (2014). The Neurology of mTOR. Neuron, 84(2), 275–291. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034

Bond, P. (2016). Regulation of mTORC1 by growth factors, energy status, amino acids and mechanical stimuli at a glance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1). http://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-016-0118-y

Adegoke, O. A., Abdullahi, A., & Tavajohi-Fini, P. (2012). mTORC1 and the regulation of skeletal muscle anabolism and mass. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(3), 395–406. http://doi.org/10.1139/h2012-009

Dibble, C. C., & Manning, B. D. (2013). Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nature Cell Biology, 15(6), 555–564. http://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2763

Mcpherron, A. C., Lawler, A. M., & Lee, S.-J. (1997). Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-p superfamily member. Nature, 387(6628), 83–90. http://doi.org/10.1038/387083a0

Armstrong, D. D., & Esser, K. A. (2005). Wnt/β-catenin signaling activates growth-control genes during overload-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 289(4). http://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00093.2005

Proud, G. C., & Denton, M. R. (1997). Molecular mechanisms for the control of translation by insulin. Biochemical Journal, 328(2), 329–341. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj3280329

Basualto-Alarcón, C., Jorquera, G., Altamirano, F., Jaimovich, E., & Estrada, M. (2013). Testosterone Signals through mTOR and Androgen Receptor to Induce Muscle Hypertrophy. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 45(9), 1712–1720. http://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31828cf5f3

Hardie, D. G., Ross, F. A., & Hawley, S. A. (2012). AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 13(4), 251–262. http://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3311

Jewell, J. L., & Guan, K.-L. (2013). Nutrient signaling to mTOR and cell growth. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 38(5), 233–242. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2013.01.004

Birk, J. B., & Wojtaszewski, J. F. P. (2006). Predominant α2/β2/γ3 AMPK activation during exercise in human skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology, 577(3), 1021–1032. http://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120972

Mounier, R., Théret, M., Lantier, L., Foretz, M., & Viollet, B. (2015). Expanding roles for AMPK in skeletal muscle plasticity. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 26(6), 275–286. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2015.02.009

Mounier, R., Lantier, L., Leclerc, J., Sotiropoulos, A., Foretz, M., & Viollet, B. (2011). Antagonistic control of muscle cell size by AMPK and mTORC1. Cell Cycle, 10(16), 2640–2646. http://doi.org/10.4161/cc.10.16.17102

Gwinn, D. M., Shackelford, D. B., Egan, D. F., Mihaylova, M. M., Mery, A., Vasquez, D. S., … Shaw, R. J. (2008). AMPK Phosphorylation of Raptor Mediates a Metabolic Checkpoint. Molecular Cell, 30(2), 214–226. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003

Bar-Peled, L., & Sabatini, D. M. (2014). Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends in Cell Biology, 24(7), 400–406. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2014.03.003

Mohammad A Humayun, Rajavel Elango, Ronald O Ball, Paul B Pencharz, Reevaluation of the protein requirement in young men with the indicator amino acid oxidation technique, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 86, Issue 4, October 2007, Pages 995–1002, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.4.995

Evaluation of protein requirements for trained strength athletes. M. A. Tarnopolsky, S. A. Atkinson, J. D. MacDougall, A. Chesley, S. Phillips, and H. P. Schwarcz. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1986

Antonio, J., Peacock, C.A., Ellerbroek, A. et al. The effects of consuming a high protein diet (4.4 g/kg/d) on body composition in resistance-trained individuals. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 11, 19 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-19

Elango, R., Ball, R.O. & Pencharz, P.B. Amino acid requirements in humans: with a special emphasis on the metabolic availability of amino acids. Amino Acids 37, 19 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-009-0234-y

Marinangeli CPF, House JD. Potential impact of the digestible indispensable amino acid score as a measure of protein quality on dietary regulations and health [published correction appears in Nutr Rev. 2017 Aug 1;75(8):671]. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(8):658-667. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nux025 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28969364/

Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414(6865):799-806. doi:10.1038/414799a https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11742412/

Adam-Perrot A, Clifton P, Brouns F. Low-carbohydrate diets: nutritional and physiological aspects. Obes Rev. 2006;7(1):49-58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00222.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16436102/

Kanter M. High-Quality Carbohydrates and Physical Performance: Expert Panel Report. Nutr Today. 2018;53(1):35-39. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000238 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5794245/

Dong T, Guo M, Zhang P, Sun G, Chen B. The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0225348. Published 2020 Jan 14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225348 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6959586/

Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Cheng S, et al. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(9):e419-e428. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30135-X https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6339822/

Snorgaard O, Poulsen GM, Andersen HK, Astrup A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000354. Published 2017 Feb 23. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000354 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5337734/

Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [published correction appears in Lancet. 2019 Feb 2;393(10170):406]. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434-445. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30638909/

Colombani, P.C., Mannhart, C. & Mettler, S. Carbohydrates and exercise performance in non-fasted athletes: A systematic review of studies mimicking real-life. Nutr J 12, 16 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-16

van Dam, R., Seidell, J. Carbohydrate intake and obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr 61, S75–S99 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602939

Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R, et al. Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):427-436. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4603544/

Burger KN, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, et al. Dietary fiber, carbohydrate quality and quantity, and mortality risk of individuals with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043127 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3426551/

Karl JP, Roberts SB, Schaefer EJ, et al. Effects of carbohydrate quantity and glycemic index on resting metabolic rate and body composition during weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(11):2190-2198. doi:10.1002/oby.21268 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4634125/

Chambers ES, Byrne CS, Frost G. Carbohydrate and human health: is it all about quality?. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):384-386. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32468-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30638908/

Gaesser GA. Carbohydrate quantity and quality in relation to body mass index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1768-1780. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17904937/

van Dam RM, Seidell JC. Carbohydrate intake and obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61 Suppl 1:S75-S99. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602939 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17992188/

Wylie-Rosett J, Segal-Isaacson CJ, Segal-Isaacson A. Carbohydrates and increases in obesity: does the type of carbohydrate make a difference?. Obes Res. 2004;12 Suppl 2:124S-9S. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.277 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15601960/

Zhang X, Yang S, Chen J, Su Z. Unraveling the Regulation of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;9:802. Published 2019 Jan 24. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00802 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6353800/

Melkonian EA, Asuka E, Schury MP. Physiology, Gluconeogenesis. [Updated 2021 May 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541119/

Chourpiliadis C, Mohiuddin SS. Biochemistry, Gluconeogenesis. [Updated 2021 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544346/

Schutz Y. Protein turnover, ureagenesis and gluconeogenesis. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2011;81(2-3):101-107. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000064 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22139560/

Veldhorst MA, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Westerterp KR. Gluconeogenesis and energy expenditure after a high-protein, carbohydrate-free diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):519-526. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27834 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19640952/

Gardner CD, Offringa LC, Hartle JC, Kapphahn K, Cherin R. Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults and adults with obesity: A randomized pilot trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):79-86. doi:10.1002/oby.21331 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5898445/

Astrup A, Hjorth MF. Low-Fat or Low Carb for Weight Loss? It Depends on Your Glucose Metabolism. EBioMedicine. 2017;22:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.001 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5672079/

Åberg S, Mann J, Neumann S, Ross AB, Reynolds AN. Whole-Grain Processing and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1717-1723. doi:10.2337/dc20-0263 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7372063/

Clark CM Jr. Glycemic control and hypoglycemia: is the loser the winner? Response to Perlmuter et al. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):e32-e33. doi:10.2337/dc08-2047 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19246583/

Hardy DS, Garvin JT, Xu H. Carbohydrate quality, glycemic index, glycemic load and cardiometabolic risks in the US, Europe and Asia: A dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(6):853-871. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2019.12.050 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32278608/

Venn BJ, Green TJ. Glycemic index and glycemic load: measurement issues and their effect on diet-disease relationships. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61 Suppl 1:S122-S131. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602942 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17992183/

Bao J, de Jong V, Atkinson F, Petocz P, Brand-Miller JC. Food insulin index: physiologic basis for predicting insulin demand evoked by composite meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(4):986-992. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27720 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19710196/

Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell. 2015;163(5):1079-1094. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26590418/

Gertsch J. The Metabolic Plant Feedback Hypothesis: How Plant Secondary Metabolites Nonspecifically Impact Human Health. Planta Med. 2016;82(11-12):920-929. doi:10.1055/s-0042-108340 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27286339/

Kim, Y., & Je, Y. (2016). Dietary fibre intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all cancers: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases, 109(1), 39–54. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2015.09.005.

Veronese, N., Solmi, M., Caruso, M. G., Giannelli, G., Osella, A. R., Evangelou, E., … Tzoulaki, I. (2018). Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 107(3), 436–444. http://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx082

Dietary reference intakes (DRIs). Institute of Medicine. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11537/dietary-reference-intakes-the-essential-guide-to-nutrient-requirements

2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/

Holscher, H. D. (2017). Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes, 8(2), 172–184. http://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756

Rowland, I., Gibson, G., Heinken, A., Scott, K., Swann, J., Thiele, I., & Tuohy, K. (2017). Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. European Journal of Nutrition, 57(1), 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1445-8

Conlon, M., & Bird, A. (2014). The Impact of Diet and Lifestyle on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrients, 7(1), 17–44. http://doi.org/10.3390/nu7010017

Murray, K., Wilkinson-Smith, V., Hoad, C., Costigan, C., Cox, E., Lam, C., … Spiller, R. C. (2014). Differential Effects of FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-Saccharides and Polyols) on Small and Large Intestinal Contents in Healthy Subjects Shown by MRI. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 109(1), 110–119. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.386

Maruvada, P., Leone, V., Kaplan, L. M., & Chang, E. B. (2017). The Human Microbiome and Obesity: Moving beyond Associations. Cell Host & Microbe, 22(5), 589–599. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.005

Li, Z.-H., Zhong, W.-F., Liu, S., Kraus, V. B., Zhang, Y.-J., Gao, X., … Mao, C. (2020). Associations of habitual fish oil supplementation with cardiovascular outcomes and all cause mortality: evidence from a large population based cohort study. Bmj, m456. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m456

Gavino, V. C., & Gavino, G. R. (1992). Adipose hormone-sensitive lipase preferentially releases polyunsaturated fatty acids from triglycerides. Lipids, 27(12), 950–954. http://doi.org/10.1007/bf02535570

Di Pasquale MG. The essentials of essential fatty acids. J Diet Suppl. 2009;6(2):143-161. doi:10.1080/19390210902861841 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22435414/

Das UN. Essential Fatty acids – a review. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7(6):467-482. doi:10.2174/138920106779116856 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17168664/

Kaur N, Chugh V, Gupta AK. Essential fatty acids as functional components of foods- a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(10):2289-2303. doi:10.1007/s13197-012-0677-0 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4190204/

Costantini L, Molinari R, Farinon B, Merendino N. Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2645. Published 2017 Dec 7. doi:10.3390/ijms18122645 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5751248/

Wene JD, Connor WE, DenBesten L. The development of essential fatty acid deficiency in healthy men fed fat-free diets intravenously and orally. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1975 Jul;56(1):127-134. DOI: 10.1172/jci108061. PMID: 806609; PMCID: PMC436563. https://europepmc.org/article/PMC/436563

Wainwright P.E. (1997) Essential Fatty Acids and Behavior. In: Yehuda S., Mostofsky D.I. (eds) Handbook of Essential Fatty Acid Biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2582-7_14

Holman R.T. (1997) ω3 and ω6 Essential Fatty Acid Status in Human Health and Disease. In: Yehuda S., Mostofsky D.I. (eds) Handbook of Essential Fatty Acid Biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2582-7_7

Holman R.T. (1977) Essential Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition. In: Bazán N.G., Brenner R.R., Giusto N.M. (eds) Function and Biosynthesis of Lipids. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 83. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-3276-3_48

Tang M , Liu Y , Wang L , et al. An Ω-3 fatty acid-deficient diet during gestation induces depressive-like behavior in rats: the role of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system. Food Funct. 2018;9(6):3481-3488. doi:10.1039/c7fo01714f https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29882567/

Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD003177. Published 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30019766/

Larrieu T, Layé S. Food for Mood: Relevance of Nutritional Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Depression and Anxiety. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1047. Published 2018 Aug 6. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01047 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC6087749/

https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/omega3-supplements-in-depth

Meyer, B.J., Mann, N.J., Lewis, J.L. et al. Dietary intakes and food sources of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids 38, 391–398 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-003-1074-0

McDonald, C., Bauer, J., Capra, S. et al. The muscle mass, omega-3, diet, exercise and lifestyle (MODEL) study – a randomised controlled trial for women who have completed breast cancer treatment. BMC Cancer 14, 264 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-264

Leckey JJ, Hoffman NJ, Parr EB, et al. High dietary fat intake increases fat oxidation and reduces skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration in trained humans. FASEB J. 2018;32(6):2979-2991. doi:10.1096/fj.201700993R https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29401600/

Liu AG, Ford NA, Hu FB, Zelman KM, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton PM. A healthy approach to dietary fats: understanding the science and taking action to reduce consumer confusion. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):53. Published 2017 Aug 30. doi:10.1186/s12937-017-0271-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5577766/

Zhu Y, Bo Y, Liu Y. Dietary total fat, fatty acids intake, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):91. Published 2019 Apr 6. doi:10.1186/s12944-019-1035-2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC6451787/

Salmerón J, Hu FB, Manson JE, et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(6):1019-1026. doi:10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1019 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11382654/

Dong J, Beard JD, Umbach DM, et al. Dietary fat intake and risk for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(13):1623-1630. doi:10.1002/mds.26032 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25186946/

Han J, Jiang Y, Liu X, et al. Dietary Fat Intake and Risk of Gastric Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138580. Published 2015 Sep 24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138580 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26402223/

Lowery LM. Dietary fat and sports nutrition: a primer. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(3):106-117. Published 2004 Sep 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC3905293/

Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11:20. Published 2014 May 12. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-20 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4033492/

Pahwa R, Jialal I. Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2021 Sep 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507799/

Linton MRF, Yancey PG, Davies SS, et al. The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2019 Jan 3]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343489/

Heileson JL. Dietary saturated fat and heart disease: a narrative review. Nutr Rev. 2020;78(6):474-485. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz091 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31841151/

Clifton PM, Keogh JB. A systematic review of the effect of dietary saturated and polyunsaturated fat on heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(12):1060-1080. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.010 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29174025/

Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD011737. Published 2020 Aug 21. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32827219/

Nettleton JA, Brouwer IA, Geleijnse JM, Hornstra G. Saturated Fat Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Ischemic Stroke: A Science Update. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70(1):26-33. doi:10.1159/000455681 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5475232/

Houston M. The relationship of saturated fats and coronary heart disease: fa(c)t or fiction? A commentary. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;12(2):33-37. doi:10.1177/1753944717742549 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5933589/

Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease: modulation by replacement nutrients. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(6):384-390. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0131-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC2943062/

Temple NJ. Fat, Sugar, Whole Grains and Heart Disease: 50 Years of Confusion. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):39. Published 2018 Jan 4. doi:10.3390/nu10010039 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5793267/

Linton MRF, Yancey PG, Davies SS, et al. The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2019 Jan 3]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343489/

Törnwall ME, Virtamo J, Haukka JK, Albanes D, Huttunen JK. Alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) and beta-carotene supplementation does not affect the risk for large abdominal aortic aneurysm in a controlled trial. Atherosclerosis. 2001;157(1):167-173. doi:10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00694-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11427217/

Kinlay S, Behrendt D, Fang JC, et al. Long-term effect of combined vitamins E and C on coronary and peripheral endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(4):629-634. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.051 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14975474/

Devaraj S, Tang R, Adams-Huet B, et al. Effect of high-dose alpha-tocopherol supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation and carotid atherosclerosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(5):1392-1398. doi:10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1392 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC2692902/

Erkki Vartiainen, Tiina Laatikainen, Markku Peltonen, Anne Juolevi, Satu Männistö, Jouko Sundvall, Pekka Jousilahti, Veikko Salomaa, Liisa Valsta, Pekka Puska, Thirty-five-year trends in cardiovascular risk factors in Finland, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 39, Issue 2, April 2010, Pages 504–518, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp330

Penny M Kris-Etherton, Thomas A Pearson, Ying Wan, Rebecca L Hargrove, Kristin Moriarty, Valerie Fishell, Terry D Etherton, High–monounsaturated fatty acid diets lower both plasma cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 70, Issue 6, December 1999, Pages 1009–1015, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.6.1009

Johnson GH, Fritsche K. Effect of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy persons: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(7):1029-1041.e10415. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.03.029 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22889633/

Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008;233(6):674-688. doi:10.3181/0711-MR-311 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18408140/

Jeromson S, Gallagher IJ, Galloway SD, Hamilton DL. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Skeletal Muscle Health. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(11):6977-7004. Published 2015 Nov 19. doi:10.3390/md13116977 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4663562/

James P DeLany, Marlene M Windhauser, Catherine M Champagne, George A Bray, Differential oxidation of individual dietary fatty acids in humans, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 72, Issue 4, October 2000, Pages 905–911, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.4.905

Markworth JF, Cameron-Smith D. Arachidonic acid supplementation enhances in vitro skeletal muscle cell growth via a COX-2-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304(1):C56-C67. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00038.2012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23076795/

Swanson D, Block R, Mousa SA. Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: health benefits throughout life. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):1-7. doi:10.3945/an.111.000893 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22332096/

Nichols PD, McManus A, Krail K, Sinclair AJ, Miller M. Recent advances in omega-3: Health Benefits, Sources, Products and Bioavailability. Nutrients. 2014;6(9):3727-3733. Published 2014 Sep 16. doi:10.3390/nu6093727 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25255830/

Calder PC, Yaqoob P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and human health outcomes. Biofactors. 2009;35(3):266-272. doi:10.1002/biof.42 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19391122/

Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2018;9:345-381. doi:10.1146/annurev-food-111317-095850 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29350557/

Gammone MA, Riccioni G, Parrinello G, D’Orazio N. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Benefits and Endpoints in Sport. Nutrients. 2018;11(1):46. Published 2018 Dec 27. doi:10.3390/nu11010046 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC6357022/

Dyall SC. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: a review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DPA and DHA. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:52. Published 2015 Apr 21. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2015.00052 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4404917/

Mohebi-Nejad A, Bikdeli B. Omega-3 supplements and cardiovascular diseases. Tanaffos. 2014;13(1):6-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4153275/

Ander BP, Dupasquier CM, Prociuk MA, Pierce GN. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their effects on cardiovascular disease. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2003;8(4):164-172. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC2719153/

Da Boit M, Hunter AM, Gray SR. Fit with good fat? The role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on exercise performance. Metabolism. 2017;66:45-54. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2016.10.007 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5155640/

Imamura F, Micha R, Wu JH, et al. Effects of Saturated Fat, Polyunsaturated Fat, Monounsaturated Fat, and Carbohydrate on Glucose-Insulin Homeostasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Feeding Trials. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002087. Published 2016 Jul 19. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002087 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC4951141/

Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252. Published 2010 Mar 23. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000252 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC2843598/

Hamley S. The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):30. Published 2017 May 19. doi:10.1186/s12937-017-0254-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28526025/