We have covered a lot of information in this exercise series, and now we need to turn our attention to training progression. You see, you can’t just continue to do the same thing over and over again, and expect a different result. Eventually, you are going to have to progress your training in some way, if you are to see results.

In the previous article on designing an actual workout, we walked you through how to design a single workout and a week of training. But you are unlikely to get results within a week. So you have to learn to organise your training over the longer term.

To understand how to organise your training over the longer term, we have to discuss two important topics. These are training progression and periodisation. If you want to actually achieve your goals, you need to know how to actually progress your training. At its core, periodisation is basically how you organise your training over weeks/months/years. Understanding these in more depth will help you to set yourself up for success. We will discuss training progression in this article, and then periodisation in the next article in this series.

If you haven’t already, it would be incredibly helpful to also read our articles on why exercise is important, the goals of exercise, the types of exercise we have available to us, and to have a rough idea of the general exercise guidelines. It would also be incredibly beneficial to visit our exercise hub, and read our content on resistance training and cardiovascular training, along with the rest of the articles in this series. Reading the previous article in this series on designing an actual workout would also be ideal before you get stuck into this article.

Before we get stuck in, I would just like to remind you that we offer comprehensive online coaching. So if you need help with your own exercise program or nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out. If you are a coach (or aspiring coach) and want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider signing up to our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too.

Now, let’s get stuck into understanding training progression!

Table of Contents

Understanding Training Progression

In order to continue getting stronger, more muscular, healthier or attain any sort of fitness adaptation, you are going to need to progress your program over time. This is often referred to as the principle of progressive overload. Without applying greater training stress, your body has no reason to build larger muscles, make new mitochondria etc. Therefore, you need to actually progress your program over time.

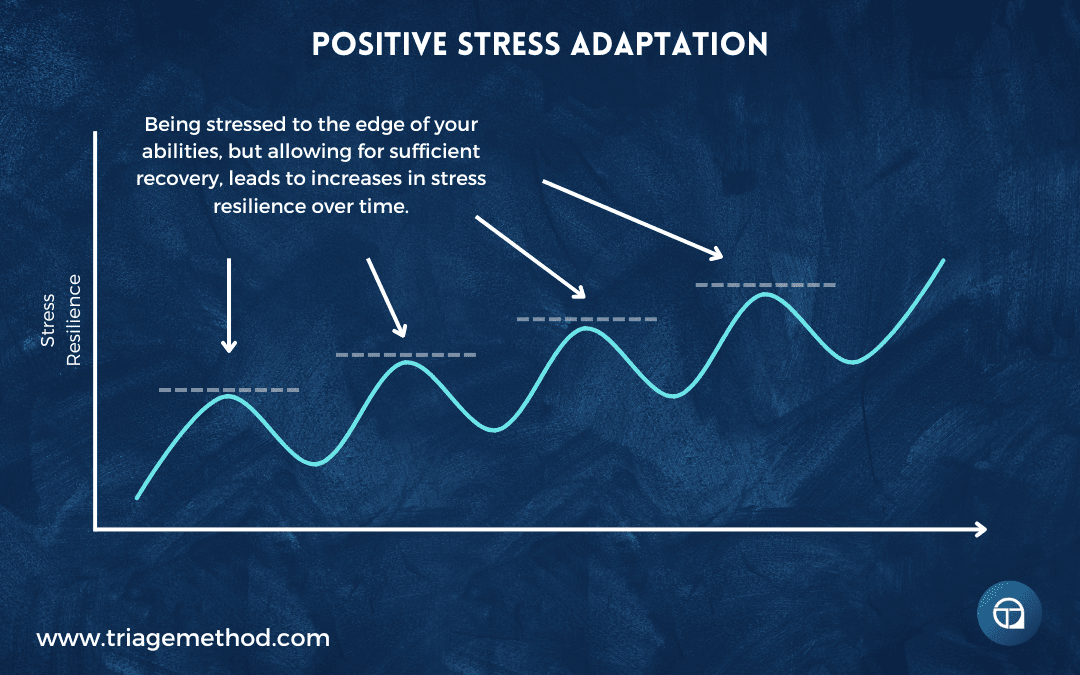

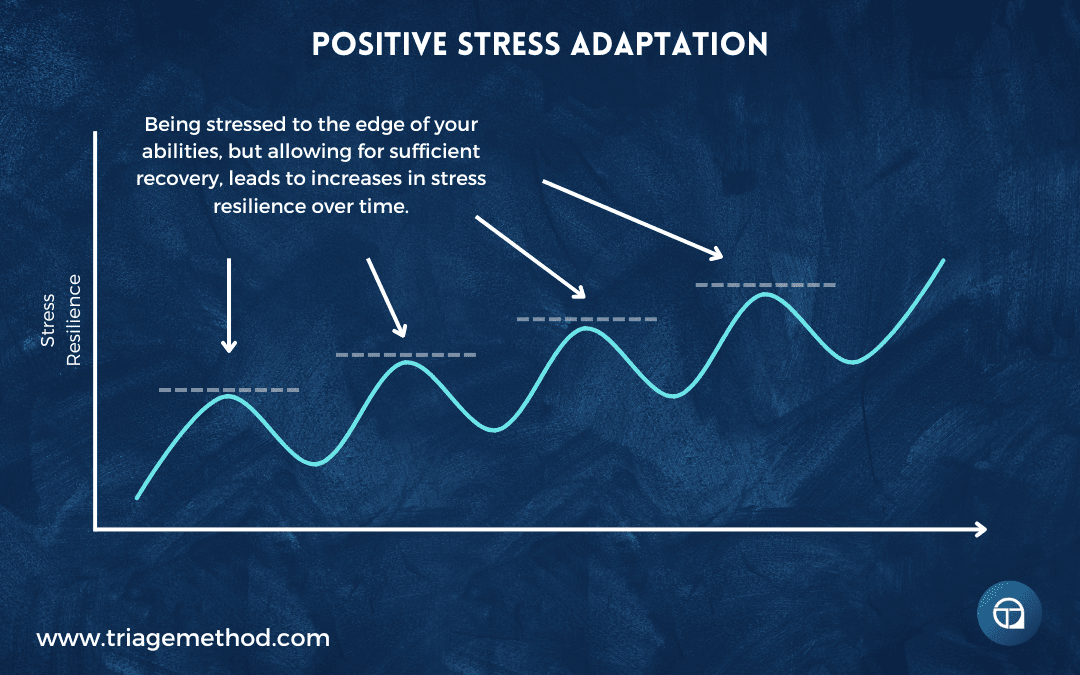

We discussed the concept of adaptation in our stress management article, and the same principles apply here. In this case, the increased stress resilience is resilience to the stress of exercise (i.e. you adapt and get fitter and/or stronger).

This is where most people actually fail in their pursuit of their goals. They either try to progress too quickly and make their training far too challenging, or they stick to what they have always done and don’t actually progress their training, and thus fail to get the results they desire.

This is where science becomes very much an art, as there are many ways to progress a program, and none that we can say for sure is superior to all others. Over time, different methods may trump others, but we will be looking after the “macro” progressions, by progressing the program throughout the year, while you look after the “micro” progressions, by adjusting the variables to be discussed on a day-to-day/week-to-week basis. This is basically the interaction between progression and periodisation, and will make sense as you get through the rest of this article and the next one.

Progressing Resistance Training

Now, you may think it’s obvious that you should progress your program, but it’s not obvious to a lot of people. If you walk into most commercial gyms, you will see trainees doing the same reps, with the same weight, for the same number of sets of the same exercise over and over again, for months, if not years. Some people don’t see the importance of actually progressively increasing the training stress. This is usually because they have previously been exposed to messages about the “perfect workout”, and that messaging may not have actually emphasised the importance of progression.

If that is you, well, I have to be the one to tell you that training progression is in fact important. Whether it’s the load on the bar, the number of reps with that load, the number of sets that you do, the duration of your cardio sessions or whatever, you need to increase the total amount of training stress you impose on your body over time.

The whole point of training in the first place is to adapt to a given stimulus. By definition of you adapting to that stimulus, it is no longer a sufficient stressor to force further adaptation and hence, if you want further adaptations, that stressor needs to be increased. In very general terms, that is why we need to have ways to progress training.

If you do the same workout over and over again, with no progression of any training parameters, your hypertrophy, strength and cardiorespiratory outcomes will be lacklustre.

Ways To Progress Resistance Training

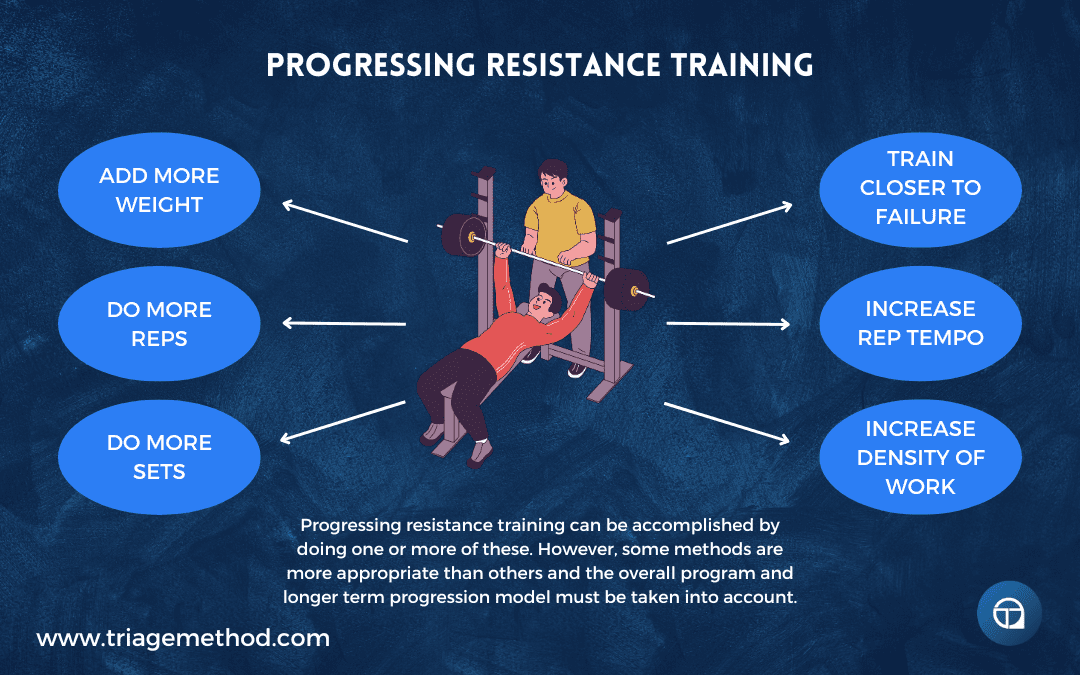

There are numerous ways you can progress your resistance training. Here are the main 6 ways that you can progress your program:

1. Progressing Load

Progressing the weight (load) you use for your exercises is probably the most straightforward way to progress training. People generally look no further than this method of progression when they think about training progression. And for good reason! It’s a pretty basic attribute of most programs, especially for beginner-intermediate lifters who can progress load on the bar relatively regularly.

We see this with a lot of our clients who have been training for <1-2 years; you can generally run a linear progression type program relatively easily with these clients. They will add a small amount of weight to most of their exercises each week, even without there being much of a change in how challenging it feels to them (especially when the diet, sleep and stress management are all dialled in). So, as a beginner, simply adding a little bit of load to the exercise can be a powerful tool.

There is a lot that goes into determining whether or not you will be able to add weight to the exercise each week, including:

- absolute strength (if you lift 300kg, then a 2.5kg increase is a much smaller relative increase than it is for someone lifting 40kg),

- level of training (to use the same example, on the other hand, the person lifting 40kg may be new to training and hence can progress faster, so 2.5kg to them could be easily achievable, even if it’s a higher relative increase vs the highly trained 300kg lifter),

- the type of exercise (sorry, you are NOT going to increase your dumbbell lateral raise on a weekly basis),

- how accustomed you are to the exercise (you should expect more regular increases in load if you are learning a movement for the first time or re-learning it)

- and other lifestyle variables (are you eating to support your training, are you sleeping well etc.).

Another thing to note with load increases is that the act of adding more load to the bar is generally a right to be earned – it means that you have already adapted to the previous stressor you applied. It’s often thought of in the opposite way around, as if the addition of the load is the necessary driver, whereas it is actually both a driver of increased training stress and an outcome of previous training stress, resulting from adaptations to the stress you applied with the last load you used. Had you not previously adapted to the previous load, you wouldn’t be lifting the load that you currently are.

The increase in load is merely one means of stepping up to another level of total training stress, so don’t get too lost in the external thing that is the load on the bar.

2. Progressing Reps

This is the next most frequently used method of progression, after increasing load. Sometimes an increase in the load isn’t possible or is too much of a jump, so instead, you can add a repetition or two, even just on one or two of your sets. If you can do this while staying more or less within the relative intensity parameters (RPE/RIR target) across all sets, you are moving in the right direction. You are still adding more overall training stress.

The concept is very simple to understand, as you simply increase the number of reps you do with a given load. That’s the simplest way of applying the increasing reps method of progression. For example, if you know you can easily do 100kg for 3 sets of 5, then you could just aim to add a repetition per week for the duration of your program (i.e. next week do 3 sets of 6 reps).

Obviously, like all of these methods, whether or not that will be practical will depend on the aforementioned variables that would determine your progression rate, but also your goal. If your goal is to train more specifically to higher intensities (e.g. if your goal is maximal strength), then continuing to add reps takes you further away from that specific goal, so you just have to keep it all in context.

However, while the above may be the most obvious way to use reps to progress your training, it can actually be quite challenging to do in practice. While adding a small amount of weight like 2.5kg to an exercise may represent a small percentage increase in effort (lets say its a 2.5% increase in the load being used), adding a single rep to an exercise may actually represent a much larger percentage increase in effort/load. For example, going from doing 8 reps to doing 9 reps actually represents a 12.5% increase in effort/load.

However, some exercises do lend themselves better to progressing reps rather than load. For example, it is usually much easier for someone to add weight to their chin ups, rather than adding reps. Conversely, it is usually much easier to add reps to isolation work for small muscle groups, rather than adding load.

In practice, what we will generally do to facilitate a progression model based on progressing reps is to simply apply a repetition range rather than a fixed rep target. For example, a rep range of 6-8, rather than a rep target of 8. On week 1, you might do 3 sets of 6 at 100kg, then 3 sets of 7 on week 2, 3 sets of 8 on week 3, and then on week 4, add a little load and jump back down to 6 reps.

This is something we like for a lot of people, as it is very simple and promotes a sense of constant progression, since an extra rep is often less daunting than consistent increases in load, and one rep increases would be very achievable for beginners. This method can be used in conjunction with relative intensity targets too (i.e. RPE/RIR), but I am getting ahead of myself.

If you need a refresher on reps, then reading the following articles would be helpful:

3. Progressing Volume/Sets

Progressing the training stress can also be accomplished by virtue of performing more overall training volume (you can read more about training volume, and why we use sets as a proxy for training volume in this article Training Volume (How Many Sets Should You Do)). This is most easily done by simply performing more total sets. This is probably the most potent means of increasing total training stress, but it also only really applies on a longer time scale. For that very reason, it’s not always easy to apply, and needn’t be of much concern at the beginner level.

What I mean by that is that a very large increase in training stress is generally not a good thing. Not only is a rapid increase in total training load a risk factor for injury, but it’s also unlikely to be of much use to a beginner trainee, since you are responsive to lower doses of training and may not yield any benefit from rapid increases.

Just because you can rapidly increase training stress does not mean that you should, as it’s not actually a reflection of what you can tolerate or recover from over and over. The purpose of increasing training stress is to actually adapt to it, not just to do more for the sake of doing more.

You see, you can actually increase overall training stress quite substantially by increasing the number of sets you do. Let’s assume that you are at the lower end of the volume recommendations and are doing something like 10 sets for a given muscle per week. Doing another 1 set per week is a 10% increase in your training volume. This is a bigger increase in loading than you can realistically get from increases in load or reps.

Assuming you are training within 2 reps of failure, you are doing a total of 30 “effective reps” (assuming the last 5 reps are the effective reps, and assuming you do 10 sets). By doing an extra set, you are now doing 33 effective reps. However, unlike if you were to simply do 3 of your sets with only 1 rep in reserve (which would also result in 33 “effective reps”), by doing another set you would also be doing all the reps of that set to get within 2 reps of failure.

These reps aren’t “effective reps”, but they are still stimulating to some degree and they are also still contributing to fatigue. So, while both situations are quite similar, you are actually creating more of a stimulus by doing an extra set.

This can more easily be seen if we calculate “volume load”. Volume load can be calculated with the formula:

Reps x Load x Sets = Volume Load

Let’s do this for three different scenarios, the control group (our baseline), the group who increases reps on 3 of their sets, and the increased set group. We are only increasing reps on three sets, to somewhat standardise “effective reps”.

Control Group: 8 reps x 100kg x 10 sets = 8,000

Increased Reps Group: (9 reps x 100kg x 3 sets) + (8 reps x 100kg x 7 sets) = 8,300

Increased Sets Group: 8 reps x 100kg x 11 sets = 8,800

This is a pretty significant increase in overall loading, by simply adding an extra set. Now, there are differences in your ability to increase reps or increase sets, and there is a lot more to this. But I hope you can see how adding an extra set does increase overall loading quite a bit. Of course, you can play around with the different equations and get different results, and this is just to illustrate the point.

It is important to also realise that adding more and more sets after a certain point does actually represent less of an increase in training stress. There is a critical drop off point, where adding more sets represents a lower increase in the return on investment to the extra stress being applied, and results in a much larger increase in the overall fatigue.

For example;

Adding 1 set to 10 sets represents a 10% increase.

Adding 1 set to 11 sets represents a 9% increase.

Adding 1 set to 12 sets represents an 8.3% increase.

Adding 1 set to 13 sets represents a 7.7% increase.

Adding 1 set to 14 sets represents a 7.1% increase.

Adding 1 set to 15 sets represents a 6.7% increase.

Adding 1 set to 16 sets represents a 6.3% increase.

Adding 1 set to 17 sets represents a 5.9% increase.

Adding 1 set to 18 sets represents a 5.6% increase.

Adding 1 set to 19 sets represents a 5.3% increase.

Adding 1 set to 20 sets represents a 5% increase.

As you can see, each subsequent set that is added, represents a lower actual percentage increase in volume. However, with each additional set, you are accumulating more and more fatigue.

Now, of course, this is only looking at a single body part in isolation, and isn’t considering what is happening with the rest of the training program. However, it is important to realise that fatigue is both local (i.e. at the muscle) and systemic (i.e. across the whole body). So, we generally don’t think it is a good idea to increase sets weekly for all body parts/exercises as a means of progression.

However, with a longer term view, you could look to increase the number of sets that you do per body part/exercise by small increments over successive training blocks. For example, if your goal is to build the biggest quads that you can, but they haven’t been growing for the past few months while doing 15 sets per week, then what you could do is push up to 17 sets for 6-12 weeks, then if you are still not growing at the rate you want, push up to 18-19, and so on. The return on investment likely diminishes as you continue to increase sets, but it is still a potent strategy to increase the total training stress that you apply, when applied appropriately.

4. Progressing Intensity of Effort

You can also use proximity to failure (e.g. RPE/RIR) as a means to progress training (you can read more about intensity of effort, RIR and RPE in this article RIR & RPE (Do You Need To Train To Failure)). This can be done in a number of ways, but is usually done by reducing RIR over time (i.e. lifting closer to failure) or lifting at a fixed effort, and progressing load and/or reps to stay at that level of effort.

1) Increasing Effort

If you use the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) ± reps in reserve (RIR) method of quantifying your relative intensity, then you could progress that relative intensity as you move through a certain phase of programming. For example, you could have an 8 week block of training where you increased your effort weekly, so that RIR decreased from 3 RIR on all sets on week 1 to 1 RIR on all sets on week 8.

This could then guide either the load increases you make each week OR the rep target increases that you make. The good thing about using RIR to guide your progression is that it is more specific to your performance on the day than predetermined load increases.

For example, if on week 6, you are due to work with 2 RIR on all sets, but you actually feel a little fatigued on that day, so that lighter weights than normal are leaving you with 2 RIR, then you can simply accept that for what it is and recognise that that is the level of training stress that will align with the 2 RIR training stress you had planned.

The load may be different and may not have progressed, but your effort is still where it is supposed to be, as opposed to going ahead with increasing load anyway and further increasing the amount of fatigue you accumulate that week.

2) Fixed Effort

In this case, you can use the RIR guidelines to guide the way in which you choose loads or repetitions, much like you would if you were increasing effort. In a fixed effort model, you may look to have a consistent level of effort each week, which is often something that is useful for beginners, who can progress pretty quickly. A small increase in load may be in line with their actual rate of progress and thus, you may not see a decrease in RIR from week to week with small increases.

If someone was following a linear progression program, where their goal is to increase load on the bar weekly by “X” kg. Then what they could do is make the load increase with that fixed RIR in mind (i.e. they increase the load, and they don’t mind if this results in a small drop in reps, as long as they stay at their RIR/RPE target). They could even use a load range (e.g. + 2.5-5kg) and then specify their increase by gauging it against the RIR target.

For example, someone may have 3 sets of 2 RIR at 80kg planned, with the number of reps being dictated by the RIR target. The next session they may aim for 3 sets of 2 RIR with 82.5kg. However, when using this method, it is helpful to at least have a rep range target to stay within (i.e. 6-8 reps).

Otherwise, many people will end up just increasing the weight, but dropping the reps quite a lot, and end up not targeting the adaptations they actually desire (refer back to our discussion on reps).

5. Progressing Tempo/Technique

This is probably one of the lesser-used means of progression, but it is an important focal point for beginners. Although it’s infrequently employed, it’s a potentially valuable progression strategy.

As I am sure you are aware, when people increase the loads that they use, they often do so while either speeding up their repetition tempo and using more momentum (e.g. bouncing the bar off your chest at the bottom of a bench press), or experiencing some type of technical breakdown (i.e. their execution of the exercise suffers).

This can lead to totally different looking reps performed at the end of the program vs those performed at the start of a program. This compromises the reliability of your measured progress, as you have changed up the training parameters to some degree. So, you would be best served to use a standardised tempo and technique when you perform your exercises.

However, you can also use tempo and technique as a means of progression.

If you previously performed 50kg x 8 reps on bench press, but you were bouncing them all violently off your chest, that is not going to have the same training effect as lowering the bar with control, pausing on the chest and pressing up with your body in a fixed position on the way up.

Therefore, rather than adding more sloppy reps, dodgy sets, or adding more weight, you may actually provide a better stimulus by ensuring your technique is as dialled in as possible. By improving your technique, you may actually end up with a much better stimulus on the target muscles.

Sometimes, you may actually be best served to reduce the weights you are using, and performing the exercises with “perfect” technique. I often call this “regressive overload”, as you are actually progressing the training stimulus by regressing the weight you are using.

You could also use a slower tempo as a means of increasing the training stress imposed by a given load. For example, going from a 3110 tempo on your bench press to a 4110 tempo is an increase in the training stress (you can read more about tempo in this article Rep Tempo and Time Under Tension, and it is especially helpful if you are unfamiliar with tempo prescription).

However, as we discussed previously, increasing “time under tension” isn’t generally a good way to progress training. Having said that, if you are going from erratic tempo from rep to rep, or you aren’t controlling your reps, then standardising your tempo is a very valid form of progression.

6. Progressing Density

This is another method of progression, although it generally isn’t one that we recommend prioritising. Progressing the density of a workout simply refers to doing the same total sets, reps and load, but condensing into a shorter time period. Generally, the easiest way to do this is to reduce the rest periods used.

So, if the rest period was 120-180 seconds, and you rested for 180 seconds last week, then you could aim to reduce that this week.

I generally don’t recommend this, unless someone is stuck for time. In general, longer rest periods are superior (within reason), so I would rather see someone try to add more load/reps with the same rest period, if not a longer one if possible, rather than shortening the rest period.

However, this method of progression may be more applicable to something like circuit training, or it can work quite well when doing something like supersetting exercises that train antagonistic muscles.

Progression Models

Now, while we have been discussing different ways in which you can progress your resistance training, you ideally don’t want to just do this in a haphazard manner. You want to follow some sort of progression model or “rules”. There are countless ways to design a progression model, and depending on what your specific goals are, certain models make more sense than others.

Choosing which method of progression is going to be dictated by your exact goals. For example, if you are trying to get stronger, it may make more sense to focus on increasing the load used. However, if you were trying to build your endurance, it may make sense to focus on adding more reps. But, assuming you are actually focused on the right variables, you still need some rules around how to progress your training over time.

In general, most progression models tend to fall into one of the following categories:

Single Progression Model:

In the single progression model, the primary focus is on steadily progressing a single variable. In most cases, this will be progressing the weight used. This progression model typically involves adding weight to your exercises, once you stay within the program parameters. For example, if you are due to do 3 sets of 8 with an RIR 2, and last week it felt a bit closer to RIR 3, then this week you may add a small amount of weight to the bar.

Oftentimes, you will see single progression models advocating for a fixed weight (or rep, or whatever variable is being progressed) increase each week. However, this is usually quite unrealistic for most individuals to do unless they start out at a very low percentage of what they are ultimately capable of doing. We will touch on this again when we discuss rate or progression, autoregulation and periodisation.

Double Progression Model:

The double progression model involves increasing two variables. For example, both the weight lifted and the number of repetitions performed with that weight. These variables don’t actually need to both be increased each week to use this model. No, the reason this is a double progression model is because you are focusing on the progression of two variables. You aren’t focused solely on a single variable. So if progress isn’t being made on one variable, perhaps it can be made on the other variable. Or perhaps it can be made on both variables (unlikely).

In practice, let’s say you choose to focus on load and reps as your two variables (these are the two most frequently used ones). You would simply select a rep range (i.e. 6-8 reps) and you would choose a weight that allows you to stay within that range for all your sets, and your target RIR/RPE. To progress your workouts, you would either look to increase the reps you are accomplishing (while staying within your rep range), or if you are at the top end of your rep range, you would increase the weight used.

You can use this method in a more informal manner, and basically just look for progress on either weight used or reps performed whenever you can.

For example, if in workout 1 you did 80kg for 7,6,6 reps (i.e. 3 sets with the target rep range of 6-8), then in workout 2 you would simply try to beat what you did previously by either adding some more weight (and still staying within the target rep range) or doing more reps with 80kg (for example, 8,7,6 or 7,7,6 or 7,7,7 etc.).

You are just aiming to do a little bit more than you did previously. The assumption is that you are still holding all the other variables constant, and most people mess this up by not holding their RIR/RPE constant (i.e. they add more reps, but they are just training closer to failure).

Alternatively, you can follow a more predetermined progression scheme. For example, you would do 80kg for 6,6,6 (again, the goal is 3 sets with the target rep range of 6-8). Then in the next workout you would go in with the target of adding reps.

Depending on how advanced you are, this will look very different. For beginners, you may be able to do 7,7,7 in the next workout, but as you get more advanced, it may be more realistic to do something like 6,6,7* in the next workout as progress isn’t as quick the more advanced you become. The next workout would be 8,8,8 (or 6,7,7, depending on how advanced you are). The goal being to get to the top of the rep range target, and then adding more weight. So once you get to 80kg for 8,8,8 the next workout you would do something like 82.5kg for 6,6,6 and begin the process of building up reps again.

*We do generally recommend adding reps to the last set, because otherwise, people tend to just drop off reps on subsequent sets due to the fatigue of pushing too hard on the first set. For example, it is common to see people try to add reps to the first set, and end up doing something like 7,6,5 or if they are very aggressively trying to progress, 8,6,4. You can end up being overly optimistic about how fast you can progress by adding reps to the first set, and as a result, end up doing the same total volume as the previous week due to subsequent sets seeing a drop off in performance.

This model allows for a lot of flexibility in progression, as you can continue to progress by adding reps and/or increasing weight. Sometimes it is easier to add weight and sometimes it is easier to add reps, and this model allows you to take this into account.

Triple Progression Model:

The triple progression model is very similar to the double progression model, except, as you might have guessed, it adds a third variable to potentially be progressed. In most cases, this third variable is the number of sets performed.

The same rules apply to this model as they do to the previous, and you can use this model in a more informal manner (i.e. looking for progress on either the weight used, reps performed or the number of sets performed in a given workout), or a more predetermined manner.

Because adding extra sets is potentially quite a big jump in overall volume, we tend to recommend following a more predetermined pattern when using a triple progression model. Adding in more sets does contribute quite a bit to overall fatigue, and as fatigue accumulates over time, you do need to be more mindful of this.

You also need to take into account that there is an “ideal” range to the amount of sets you should perform for a given muscle group. This is generally somewhere in the range of 10-20 sets, but this may not be the same for all muscle groups. So you may find that adding more sets for a certain body part results in excessive fatigue, and limited actual muscle/strength gain. As a result, you may be better off focusing on adding weight or reps for that muscle group.

In practice, following a predetermined triple progression model, we could do something like we described in the double progression model, except now when you get to 80kg for 8,8,8 you would add another set. So the next workout may look something like 80kg for 8,8,8,6. In subsequent workouts, you would then look to get up to 8,8,8,8 before potentially adding more weight, or another set.

You can also decrease the number of sets performed, every time you add weight. So you may have a range for your sets (i.e. 3-5 sets) and a range for your reps (i.e. 10-12 reps). Once you get to the top of the range for both (e.g. 5 sets of 12 reps), you would add weight, but drop down to the bottom end of the range (e.g. 3 sets of 10 reps) and look to build this back up over time.

This progression model can be really handy, especially as you get beyond the beginner to intermediate ranks. However, it can also be quite fatiguing if you aren’t careful. It does also mean your workouts can vary quite significantly in length. The difference between doing 3 sets and doing 5 sets, can actually be ~10 minutes. So your workouts can end up being significantly longer when you add sets.

Progression Overview

Each progression model has its pros and cons, and it is important to keep in mind that there is an unequal distribution between the stimulus provided by increasing each variable. For most people, and in most situations, increasing the load is probably the easiest thing to focus on. It is generally the lowest actual increase in the stressor, as you can add an incredibly small amount of weight.

Adding reps is probably a slightly bigger jump in the overall stressor, however, it may sometimes be easier to do than adding more weight. Adding sets is generally the biggest increase in the stressor, but it does increase workout time quite a bit and can lead to overtraining if not done in a systematic way.

Fatigue accumulates over time, so it is important to keep the longer term in mind when you are choosing on your specific progression model(s). Most beginners make the mistake of increasing their training stress too quickly, and as a result, they see a marked drop in performance in the subsequent weeks. Whereas more advanced trainees have realised that it is much better to slowly progress in small increments, rather than destroying themselves in a single workout.

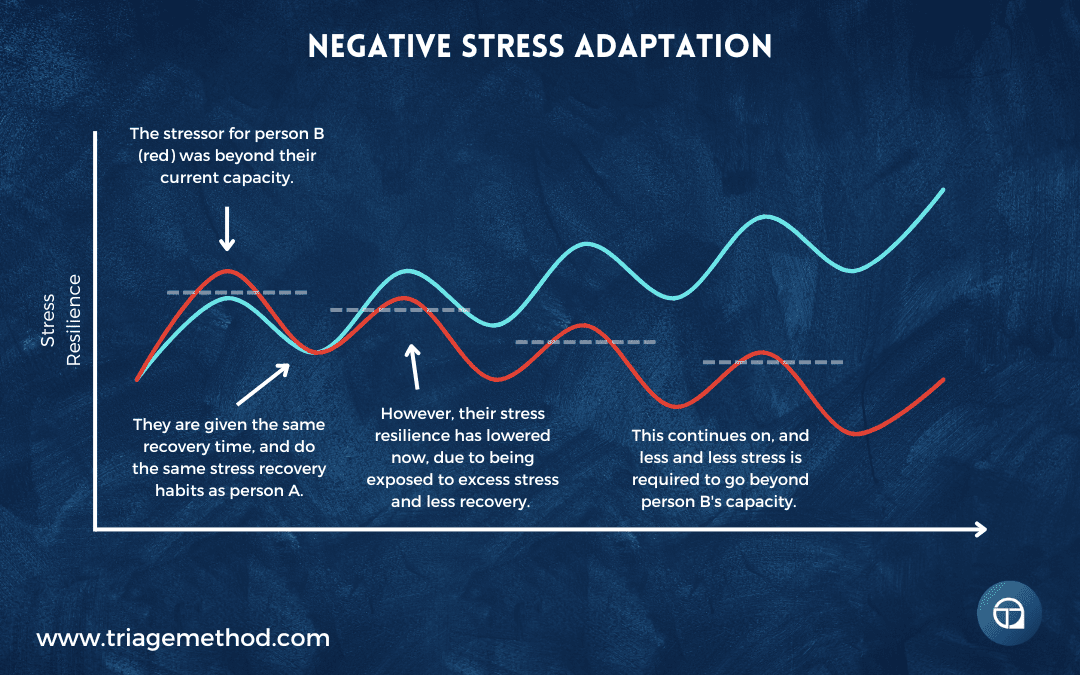

We talked about this very same situation in the stress management article when talking about negative stress adaptation.

It is also important to realise that you can also run different progression models in a given workout program. For example, you may do a triple progression model for your quads, while doing a double progression model for your delts.

However, most beginners should just focus on a single progression model, and maybe a double progression model as they get more comfortable with knowing when to push and when to just maintain.

Rate of Progression

Now, our discussion on progression models does assume that you will be making relatively consistent progress. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. Unless you have the rest of your lifestyle variables dialled in (i.e. your diet, sleep and stress management), you likely aren’t going to progress every week and you may in fact actually regress some weeks.

This is normal, and to be expected. We generally solve this by combining a progression model with some sort of autoregulation methods, which we will discuss in a moment. However, before we can discuss that, we have to discuss what is a realistic rate of progression.

The first thing to keep in mind with this is that most people have the wrong understanding of how progression works. Most people believe that you must increase the training stressor to make progress, and that by increasing the training stress you are somehow forcing progression. However, this is wrong.

You aren’t somehow training beyond your capacity, and by doing so, forcing your body to adapt. You don’t get to “borrow” progress from your future self. You are always only able to train within your capacity.

This is especially true of intensity. You can’t just lift 110% of what you are capable of lifting. You can only ever possibly lift 100% of what you are capable of lifting.

You can somewhat borrow with regards to volume, but this isn’t necessarily going to lead to adaptation, and usually, it is just increasing fatigue. Effectively, you are just draining your battery a bit more, and thus you have to fill it up for longer the next day. This is why it is generally much easier to “overtrain” by way of excessive volume, rather than excessive intensity (at least with regards to resistance training).

The reality of progressive overload is that you have to increase the stressor to just stay applying the same magnitude of stress. If you simply do what you previously did, you would actually be under-dosing the stimulus, as you have already adapted to that level of effort. You actually have to put in a decent amount of effort to continue applying the same level of stimulus.

As we discussed in the stress management article, being stressed to the edge of your abilities leads to an increase in your abilities, assuming sufficient recovery. You can’t somehow go beyond your abilities. The only way you can really do that is by doing an excessive amount of overall volume, but this is really just going beyond your recovery capacity rather than your actual ability to perform a workout.

As you can also see from the above image, if on the second workout you were to only apply a stress up to the same level that was applied on the first stressor (i.e. the second grey dotted line from the left hand side of the graph was the same, but the the stress applied (the second peak of the light blue line) only got as high as the first grey dotted line), then you wouldn’t likely progress. You have to get close to the edge of your abilities to trigger adaptation.

This is illustrated quite nicely in Lewis Carroll’s “Through The Looking-Glass”, where the Red Queen and Alice are constantly running, but remain in the same place.

“Well, in our country,” said Alice, still panting a little, “you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you run very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.”

“A slow sort of country!” said the Queen. “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

Let’s say you do a workout where you do 3 sets of 8 reps at 100kg. Let’s say this was 100% of what you were capable of doing. As a result of this workout, you get a little bit stronger, let’s say 2% stronger. So next week, if you were to lift the same weight as you previously did (i.e. 3 sets of 8 reps at 100kg), you are no longer working at 100% of your capabilities. You are now working at ~98% of your capabilities. So you have to increase the weight to continue applying the same 100%.

This may seem like semantics, but it is very important to understand. Progression for the sake of progression is not the goal. You aren’t just arbitrarily adding weight, reps and/or sets so that you can “progress” on paper. No, you are only progressing these variables because you have adapted to the previous stimulus, and now need a bigger stimulus to even be able to apply the same relative level of stimulus.

Progression only comes AFTER recovery from the previous stimulus. So recovery is a crucial part of the whole process. As a result, when recovery is lower, due to whatever reason (poor sleep, poor nutrition, pushing too hard in training, excess stress etc.), you may actually not have recovered sufficiently to be able to progress your training.

You see, to adapt to the training stimulus and get 2% stronger, you actually have to go through a period of time where you are actually weaker. You intuitively know this, as you have likely seen a drop off in your performance after a certain amount of stimulus is applied, or you have likely felt like your muscles were significantly weaker the day(s) after you trained them.

This is the GAS (General Adaptation Syndrome) principle we discussed in the stress management article at play. You apply a stressor, and to adapt to the stressor, you actually go through a period of reduced capacity. If you try to apply more stress before you are recovered, you may just create a bigger recovery debt. Alternatively, if you wait too long before you apply more stress, you may actually have started to detrain (i.e. lose the adaptations).

Similarly, if you don’t do the things that allow your body to sufficiently recover (i.e. sleep enough, eat enough, hydrate, manage your stress etc.), then you may end up not being able to pay back that recovery depth and thus you don’t actually recover and adapt.

This is why autoregulation is so important for training progression. It allows you to apply the right amount of stress, so that you can recover and adapt. However, it is still important to understand what a good rate of progression actually looks like.

- For most beginners, a 1-2% rate of progression per week is quite realistic. Some may see more than this, especially if they are very new to training, but for most beginners, a 1-2% rate of progression per week would be realistic.

- For intermediate trainees, a 1-2% rate of progression every 2-6 weeks is probably more realistic.

- For advanced trainees, a 1-2% rate of progression every 3-12 months is probably more realistic.

Now, you may see a faster rate of progression than this, especially if you are coming back from injury, are taking drugs, or you are new to the exercise. But these progression rates would be quite typical.

It is quite typical to see faster rates of progress for the first 4-6 weeks or so of performing a new exercise. However, this is just due to getting better at performing the movement (i.e. the skill of performing that movement), rather than a true reflection of your actual muscular or training progression. This is especially true the more advanced you are.

You frequently see advocates of training to failure fall victim to this 4-6 week effect. You will see them making big jumps in progress each week (i.e. adding 10-20kg to the bar), but the reality is that they were simply not truly training to failure in the previous workouts, as they hadn’t mastered the skill of lifting to failure on this exercise.

People who train to failure often frequently swap out exercises, and as it usually takes about 4-6 weeks to really hit your groove with being able to perfectly execute an exercise to your fullest ability. They are basically training below capacity, which allows for fast “progress”. They aren’t actually progressing faster, they are still just mastering the skill of performing that exercise optimally.

However, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. You can actually get quite strong doing this, as it is basically just forced RIR training. You are forced to spend a few weeks training below your true ability (i.e. keeping more RIR), and then over the weeks you get closer and closer to failure, before switching out to something else (i.e. increasing your RIR again).

Now, using this 1-2% rule isn’t foolproof, but it is still quite helpful. It does serve to highlight why most people generally focus on progressing the load they use, as it is much easier to progress your workouts in very small increments by increasing load. Increasing load is incredibly versatile, as it allows for very small, incremental progression, and thus allows you to continue stimulating your muscles sufficiently. However, sometimes it does make more sense to increase reps, and less often, it can also make sense to increase sets.

Ultimately, we just want to progress training over time, so that we are always training at the edge of our capabilities. This leads the body to adapt, and essentially overcompensate.

The concept of progressive overload is often discussed with the ancient Greek story of Milo of Croton. There are many versions of the story, but the essence of the story is the same. Milo was an ancient Greek wrestler, who wanted to become stronger. He devised a unique method to achieve this goal.

Milo began by lifting a newborn calf onto his shoulders. Each day, he would repeat this action, carrying the calf as it grew bigger and heavier. As the calf grew into a bull, Milo’s strength also increased proportionally. Eventually, he became strong enough to effortlessly lift and carry the fully-grown bull.

This story is basically describing progressive overload. By continuing to lift and carry the calf as it grew, Milo slowly got stronger. The increase in weight caused by the growth of the calf caused his muscles to adapt and grow stronger. This is the concept of progressive overload. By gradually increasing the demands placed on the body during training, you stimulate continued adaptation (strength and muscle gains).

Autoregulation

Once you are no longer a beginner, you are unlikely to see improvements week to week. Progress slows the more advanced you get. Another issue with progression is that progress rarely happens linearly. Some weeks you will progress more, and other weeks you will progress less. And some weeks, you may actually regress. This all depends on how well designed your program is, and how tailored it is to perfectly meet you at the right point in the adaptation curve.

If you try to train again too soon or you do an excessive amount of work, you may be underrecovered when it comes time to train again. Conversely, if you have too big of a gap between training sessions, then you may have already started to detrain. To some extent, this can be solved with better training programming.

However, a big issue is that, unless you have every other variable in your life dialled in (i.e. your sleep, stress management, hydration, nutrition etc.), you are going to have variable recovery and performance. So it is very difficult to provide the right amount of stimulus for where you are on the curve.

This is where autoregulation comes in. Autoregulation is quite simply adjusting the stimulus based on how recovered and ready to perform you are on a given day. Instead of rigidly following a predetermined program, with autoregulation, you can make adjustments before and during your workouts to better account for physiological and psychological readiness to perform.

Having the ability to auto-regulate your training is incredibly important when it comes to managing fatigue and progressing longer term. It is especially important if you are just an average person and you have real life to deal with. It is incredibly hard to have your sleep and stress management perfectly dialled in, for example, when you are busy at work and you also have a newborn. If your program is telling you that you are due to increase the weights you are lifting in this workout, but you are over-stressed and under-slept, it is unlikely that you will be able to increase the weights.

As a result, what usually happens in these situations is you go in and try the workout, realise that even your warm up weights feel too heavy and you go home, or you try to increase the weights anyway and you either end up injured, demotivated for not even nearly hitting your weights, or you dig yourself even deeper into recovery debt.

However, if you were to use an autoregulatory approach to your training, you would be able to go into that workout and adjust the variables to allow you to get the right amount of stimulus for your over-stressed and sleep deprived state. By simply adjusting the variables based on your recovery and perceived readiness to train hard, you would be able to provide a much more appropriate stimulus, and thus you would actually get better results.

So, how do we do this in practice? Well, the first step is to have clear goals and rationale for each part of the program. If you know that some exercises are there for strength development, while others are there for muscle development, you can make more appropriate adjustments. Similarly, if some exercises you are focusing on progressing the load or the reps, then again, you can make more appropriate adjustments (if you haven’t already, then reading Exercise Selection, Variety and Ordering will help you better understand this).

Assuming you have clear goals and rationale for each part of the program (this article Designing An Actual Workout Program can help you better understand each part of a workout), then we actually get to making adjustments. By far the easiest way to make adjustments is to first have a clear RPE/RIR goal for each exercise. Having a clear target for the level of effort you should be putting into each exercise makes it so much easier to actually adjust the variables so you stay within that RPE/RIR target.

With this RPE/RIR target, you can either adjust the weight you use, or the reps you perform. If you find that the weight you intended to use is feeling excessively heavy, you can just reduce the weight by 5-10% (and sometimes more), and still stay within your overall program structure. This is the most straightforward way to use an autoregulation approach to your training.

However, sometimes, you may actually want to keep the weight the same, and instead, adjust the amount of reps you do. This can be tricky, and usually people do this because their ego is attached to the specific weight being lifted. For example, if you use 100kg for your exercise, you may simply not want to drop below this and would instead prefer to just do fewer reps with 100kg. Sometimes it needs to be done for practical reasons, such as having fewer weight increments to use. For example, if you are using only the 20kg bar for your exercise, it is incredibly difficult to reduce the weight used, and thus it may be more practical to reduce the reps performed.

The issue with reducing reps to stay within your RPE/RIR target is that you run the risk of falling out of the rep bracket, and thus potentially getting a different stimulus than intended. For example, going from doing sets of 8 to sets of 3 is a completely different workout. So, when reducing reps, we do generally still recommend that you pay attention to the rep targets, and that you aren’t reducing reps too dramatically.

You can also take an autoregulatory approach to the number of sets you perform too. If you are feeling good with the weight and you still want to hit the rep target, you could simply adjust the number of sets you do. You could simply drop off a few sets, and thus reduce the overall fatigue generated from that workout. This can be quite effective for those days when you are under-recovered, but you still feel like you can perform quite well.

In most cases, you are better off doing some sort of exercise, even if it has to be heavily modified to reduce the overall level of fatigue generated from the workout. However, sometimes you are going to just need to call off the session entirely, and focus on recovery instead.

Now, it should be noted that if you are constantly having to switch up your training and reduce the intensity/volume, then you may be better off just re-analysing the program design or your lifestyle choices. Yes, for sure, not every workout is going to be a phenomenal workout, but if you are adjusting your workouts dramatically each week you may need to work to tailor your program to match your life more accurately. There is no shame in this, and while this likely means you will be doing less, it does actually usually lead to better results as you aren’t constantly trying to fit a square peg into a round hole all the time.

It should also be noted that autoregulation isn’t just about taking it easy, it also lets you know when to push harder. On the days when you feel super recovered and ready to push training, you can also take advantage of these.

Of course, you do still have to be aware of the upcoming training too. There is no point having an absolutely phenomenal training day where you really push yourself, if it means the subsequent training days are all bad training days because you are still recovering from having pushed so hard.

Autoregulation could actually be considered a periodisation model, but we will discuss this further in te next article in this series.

Progressing Cardio

We have been talking a lot about how to progress resistance training, but we haven’t really touched on progressing cardio. Progressing cardio is actually more straightforward than resistance training, while also being more complex.

It is straightforward by virtue of basically boiling down to much of the same stuff we have already discussed with regards to resistance training, and just doing a little bit more than you previously did. And it is more complex because while resistance training is generally used to promote strength and muscle gain, there are infinite possible reasons to use cardio.

This is especially true when using cardio for sports. So you have the ability to really optimise for specific adaptations within the general framework of “just doing more”. But with this in mind, let’s discuss how to progress your cardio.

Most of the same stuff we discussed with regards to progress and resistance training also applies to progressing cardio. So, rather than going through every single way you could potentially progress your cardio, I just want to focus on the most commonly used ones. However, do realise that there are actually more ways to progress your cardio, and that the same basic rules apply to cardio as it does resistance training. Especially remember that you can’t force progress, and that you can only work within your capacity. You don’t get to borrow progress from the future to perform today.

I don’t want to just leave you with some vague idea of how to progress your cardio, so let’s discuss how you could progress the two most commonly used cardio protocols; LISS/Zone 2 cardio and HIIT cardio (reading these articles will really help your understanding: Why Do Cardio Training?, Cardio Programming and Foundational Cardio Protocols).

Progressing LISS/Zone 2

As we discussed previously, LISS/Zone 2 is the predominant cardio method used to improve your aerobic fitness. The general protocol for LISS cardio is 45+ minutes of cardio at a heart rate that is roughly 60-70% of your maximum heart rate, or an RPE of 4-5 out of 10.

So, with this protocol in mind, we can progress in a number of ways. The most obvious way is to simply do more overall volume of cardio. This can be achieved by spending more time doing LISS cardio. For example, if you were doing 45 minutes, you would just slowly build this up to 60 minutes or maybe even as far as 90 minutes.

You could also do more volume by increasing the number of LISS cardio sessions you do per week. You would ideally increase this slowly, and we wouldn’t recommend jumping from doing 1 x 60 minute LISS session to doing 2 x 60 minute LISS sessions. Instead, you would do something like a 45 minute session and a 30 minute session. You would then work to build these up over time.

While LISS cardio is typically done at a low intensity, you can slightly increase the intensity by working at a slightly faster pace or increasing the resistance on the cardio machine. There is a limit to how much you can push the intensity before it stops being LISS cardio and you move into some sort of moderate intensity or high intensity cardio. However, as you get fitter, the same level of intensity that you were previously working at will no longer be as challenging, and you will have to do more work to stay at the right intensity level. This is the very same principle at play that we discussed about resistance training and the Red Queen. As you progress, you have to do more to even stay providing the same stimulus.

In practice, this might look like using a higher resistance level on the cardio equipment you use (i.e. increasing the resistance level on the cardio bike). Increasing the speed at which you use on the cardio equipment (i.e. increasing the speed of the treadmill or pumping your arms and legs faster while using the elliptical machine). It may involve changing to a harder exercise for your cardio (i.e. switching from the regular bike to a fan bike, or running on the flat to incline running). It could also just mean naturally progressing the exercise, so the level of intensity matches your fitness level. For example, going from walking to jogging to running, all while staying at roughly the same heart rate and RPE level.

You can also progress your LISS cardio by increasing the density of work you get done in a given unit of time. For example, you could run further than you have previously run in 60 minutes, or you could complete your usual 10km run in less time (i.e. you ran faster). This is still assuming that you are working at the right intensity level and aren’t just pushing intensity excessively high to increase the density of work. You could also look to progress the number of calories you burn during your session, which usually means either pushing harder or moving faster.

Effectively, to progress your LISS cardio, you are either increasing the volume, intensity or density of your workouts. These do all generally feed into each other in some way, and the exact method you choose depends on why exactly you are using LISS cardio. If you are using it to train for a marathon, then you may choose to focus on progressing the time spent doing cardio (time is a proxy for distance). If you are trying to use LISS cardio to burn calories, you will naturally look to progress the calories burned either by doing more total LISS or by increasing an intensity or density metric within your cardio.

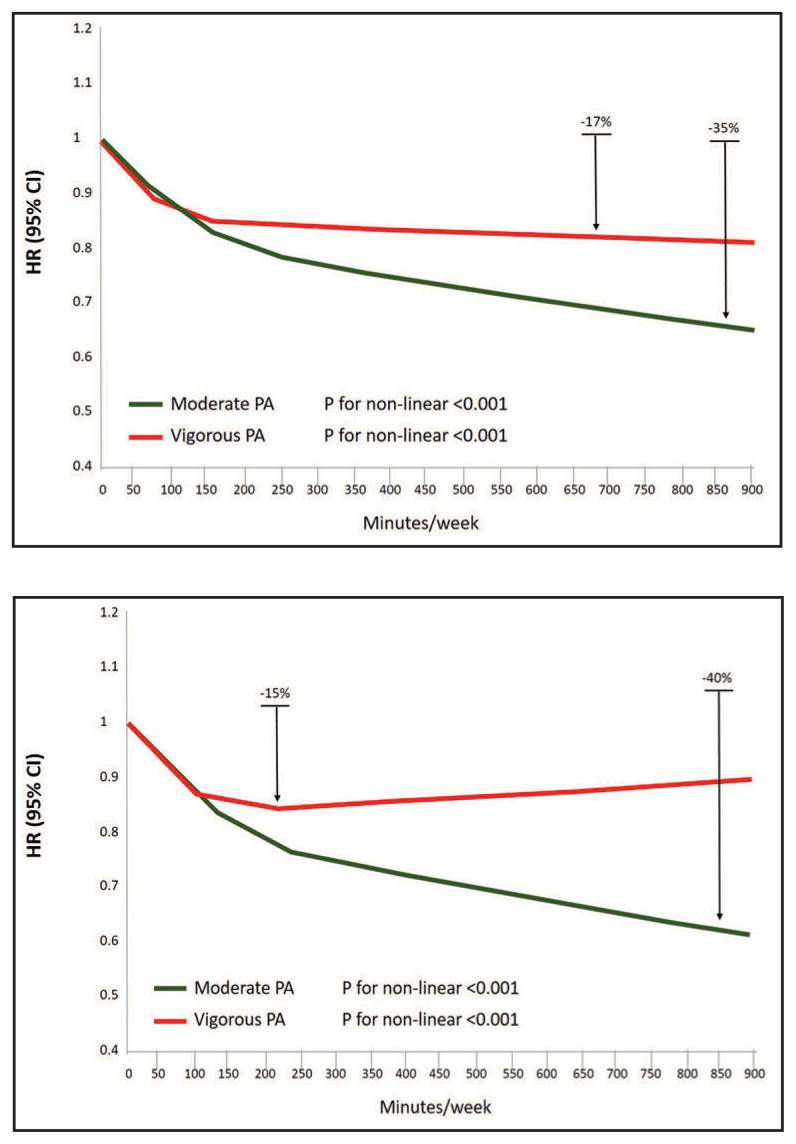

Much like with resistance training, there does seem to be a drop off in the rate of progress as you get more advanced (i.e. you get fitter). There is a drop off in the return on investment for aerobic fitness after some point, meaning the more effort you put in, the less return on investment you get.

Most people aren’t usually limited in their absolute ability to progress their aerobic fitness, and instead are simply limited by the amount of time they can allocate to getting aerobically fitter. While there may be a physiological upper limit to how strong or muscular you can physically get, and you may get close to that, it is unlikely that you will ever even get close to approaching any physiological aerobic fitness limit. This is very much evidenced by the fact that aerobic fitness doesn’t seem to drop off as people age, as long as the individuals keep training. Whereas despite continued training, strength and muscle mass do seem to still decline with age.

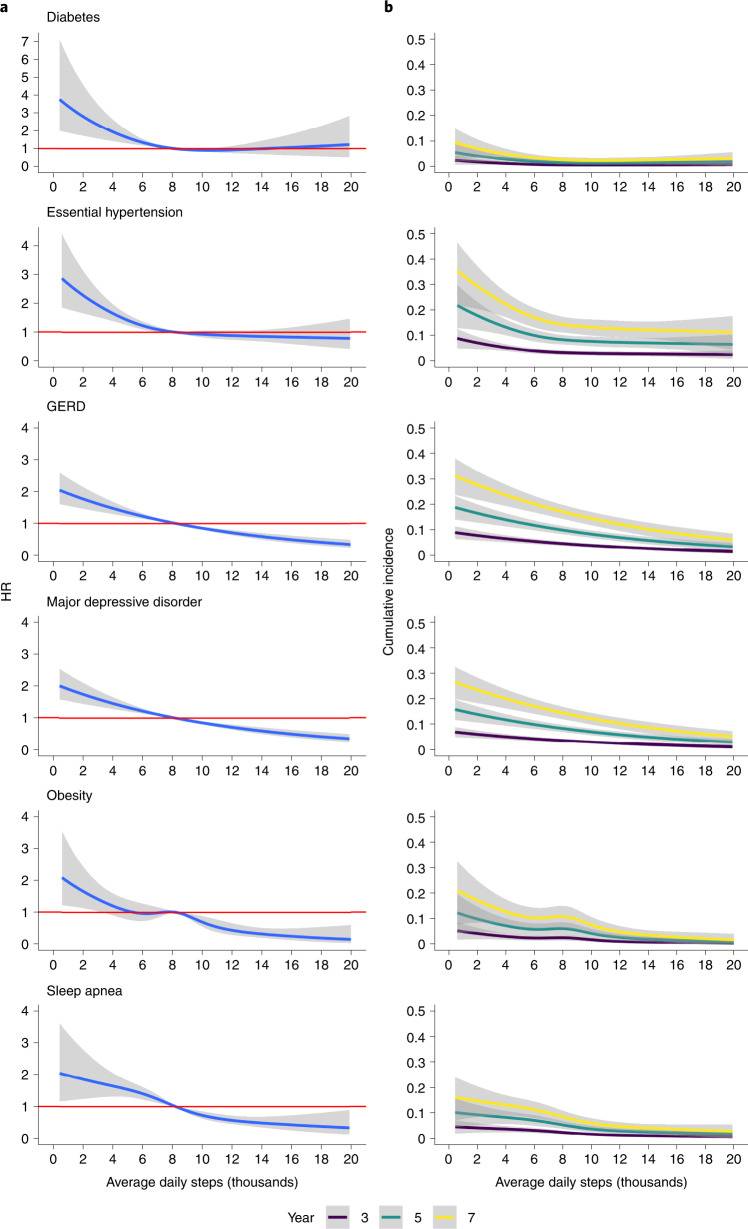

Similarly, while some benefits seem to drop off with more and more daily steps, there are still further benefits to be had in some areas with a higher step count.

Progressing HIIT

Much like with LISS, progressing HIIT also really boils down to progressing either volume, intensity or density. The exact metric you focus on progressing depends on the reasons you are using HIIT. If you are using HIIT for improvements in general fitness, health and/or to burn calories, you do have a good bit of flexibility with how you choose to progress HIIT. However, if you are using HIIT to improve sporting performance, you do have to be a bit more precise in what you choose to focus on.

A very common HIIT style workout may look something like 3 sets of 30s work, 90s recovery. We could progress this by simply doing more overall volume. This could be accomplished by doing more sets. Moving from 3 sets up to 4 sets, and then to 5 sets, for example. This is a very simple way to progress HIIT, although the more sets you do, even with relatively complete rest, the more aerobic in nature the intervals are likely to become.

You could also progress this by performing longer work intervals. For example, going from 30 seconds to 35 seconds, then 40 seconds, and so on. Of course, this may change the exact adaptations you are targeting (e.g. 30 second intervals are quite different from 60 second intervals). You also have to factor in that longer intervals are also more aerobically fuelled than shorter intervals.

You can also progress HIIT volume by doing the HIIT intervals more frequently. For example, if you are currently only doing intervals 1 day per week, you could do them 2 days per week. However, HIIT can be quite fatiguing, especially if performed frequently. So this may lead to poorer recovery, and thus poorer performance in subsequent sessions (and thus poorer results).

HIIT can also be progressed in intensity. This effectively boils down to pushing hard during the work intervals. This can be measured in a number of ways, such as:

- Higher RPE,

- Higher output (e.g. watts),

- Higher resistance (e.g. a higher level of resistance selected on the cardio machine),

- Higher heart rates,

- More calories burned,

- And a myriad of other ways to potentially quantify the level of work put into each effort.

Much like with LISS, you can also change the exercise to a harder one to increase the intensity. For example, instead of doing your HIIT on a regular exercise bike, instead perform it on a fan bike. You can also use exercises that use more overall muscle mass, like the elliptical, the fan bike, the rowing machine or the vertical climber.

Finally, you can also try to progress the density of your HIIT. This can be measured by some metric that tracks overall output for the session, such as distance travelled or calories burned. This can be accomplished in numerous ways, although most often people try to accomplish it by increasing the intensity of effort on the work periods, shortening the rest periods and/or doing active recovery rather than passive recovery (i.e. they stay moving during the recovery periods).

What is really important to realise about progressing HIIT is that the return on investment for HIIT does seem to drop off relatively quickly. While you can progress aerobic training almost indefinitely, progressing HIIT training results in much more fatigue relative to adaptations. The rate of progress seems to drop off very quickly, and trying to do more in an effort to somewhat push progress to continue just results in the accumulation of fatigue. So, this is important to keep in mind.

Cardio Progression

Ultimately, just like with resistance training, you should be looking to progress your cardio training. This is sometimes not obvious to people, as they will go into their resistance training workouts with the “progressive overload” mentality, but then just do the same cardio workouts they have always done. This can certainly be productive, especially because progress can take a long time when you get more advanced. However, if you want to really improve your cardio, you should be looking to progress it in some way, over time.

Similarly, adhering to a strict plan with absolutely no wiggle room likely isn’t going to lead to the best results. You do want to have some degree of control over how hard you push on any given day. So we do encourage the use of an autoregulation approach to cardio too. Much like with resistance training, this often means either manipulating the intensity (i.e. pushing yourself a little bit less or potentially more, depending on recovery) or volume (i.e. doing less or more, depending on recovery).

Cardio does take a long time to progress, especially once you are beyond the beginner stages. So you are going to need to tweak the variables over time, and autoregulation allows for this. Once you have a clear idea of the amount of cardio needed to maintain or progress, you can much better manage the overall stimulus input based on how well you are recovering.

Tracking Progress

It is important to actually track your progress and how you perform in your training. I have been discussing progression as if it is a given that you are actually tracking your workouts, however, having coached many people, I know this generally isn’t actually the case.

Most people are actually incredibly haphazard in their training. They simply go in and do what they feel like on the day. This isn’t necessarily bad, and we do always encourage people to exercise in general, regardless of if it is tracked. So doing some exercise, even if you don’t track it, is generally a good idea.

However, if you want to make consistent progress, it makes sense to track your workouts. This allows you to more accurately progress the program week to week. If you know what you did last week, you can more precisely progress the program this week. Whereas if you just go into a workout and try to remember what you did last week, you are more than likely going to under- or over-dose the stimulus.

Tracking your workouts also allows you to make much better adjustments to the program to continue making progress. If you can look back over your workouts over the last few weeks and months, you can begin to piece together what is working well for you and what isn’t. You can then use this information to create a much better program, that is more tailored to your specific needs and produces better results for you.

Actually tracking your workouts doesn’t need to be complicated. Effectively, all you need to do is write down what you did during your workout. You can do this with pen and paper, or you can do this in the notes app on your phone. There are also many specific tracking apps that can be useful for tracking your workouts too.

Many people overcomplicate what they track, when in reality, you just want to keep track of what you did in a given workout. So for resistance training, this may include stuff like the weight you used, how many reps you did with that weight, how many sets you did, the RPE/RIR of those sets and perhaps also how you felt going into the workout, and how you felt after finishing the workout. With cardio, it does depend a bit more on the exact specifics of why you are using cardio, but it still boils down to tracking what you actually did during the workout. So for cardio, you may track stuff like calories burned, time spent doing cardio, distance accomplished, RPE, average pace, wattage, average heart rate, heart rate lows/highs or whatever other metrics make sense for the exact cardio protocol you are using.

You can then use this information to ensure you are actually progressing things over time. This can both be done on the workout to workout basis (i.e. looking at what you did last week and trying to do a little bit more this week) and on a longer term basis (i.e. looking at what you did weeks/months ago, and comparing that to what you are doing today).

Unfortunately, most people won’t spend the time to actually track their workouts, and they will get poorer returns on their investment as a result. You don’t have to be excessive with your tracking, however, it makes sense to at least keep track of the important variables and ensure you are progressing them over time.

Training Progression Conclusion

Hopefully you can see why training progression is important. You have to actually progress your training in some manner, if you actually want to get results. You can’t just keep doing the same thing over and over and hope to get different results.

Having a clear plan for how you are going to progress your training, whether that is resistance training or cardiovascular training, is a good idea. Hopefully after reading this article, you have a clearer idea of how to actually do this.

In the next article in this series, we will discuss periodisation, as that will allow us to really round out this conversation.

As with everything, there is always more to learn, and we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface with all this stuff. However, if you are interested in staying up to date with all our content, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter and bookmarking our free content page. We do have a lot of content on how to design your own exercise program on our exercise hub.

If you would like more help with your training (or nutrition), we do also have online coaching spaces available.

We also recommend reading our foundational nutrition article, along with our foundational articles on sleep and stress management, if you really want to learn more about how to optimise your lifestyle. If you want even more free information on exercise, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course. We do also have an exercise program design course in the works, if you are a coach who wants to learn more about effective program design and how to coach it. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

The previous article in this series is about Designing An Actual Workout Program and the next article in this series is Periodisation, if you are interested in continuing to learn about exercise program design. You can also go to our exercise hub to find more exercise content.

References and Further Reading

Bishop PA, Jones E, Woods AK. Recovery from training: a brief review: brief review. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(3):1015-1024. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816eb518 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18438210/

Spiering BA, Mujika I, Sharp MA, Foulis SA. Maintaining Physical Performance: The Minimal Dose of Exercise Needed to Preserve Endurance and Strength Over Time. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(5):1449-1458. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003964 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33629972/

Lloyd RS, Cronin JB, Faigenbaum AD, et al. National Strength and Conditioning Association Position Statement on Long-Term Athletic Development. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(6):1491-1509. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001387 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26933920/

Stone MH, Hornsby WG, Haff GG, et al. Periodization and Block Periodization in Sports: Emphasis on Strength-Power Training-A Provocative and Challenging Narrative [published correction appears in J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Nov 1;35(11):e290]. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(8):2351-2371. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004050 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34132223/

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):674-688. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000121945.36635.61 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15064596/

Blanchard S, Glasgow P. A theoretical model to describe progressions and regressions for exercise rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2014;15(3):131-135. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.05.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24913914/

Liu CJ, Latham NK. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(3):CD002759. Published 2009 Jul 8. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4324332/

American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19204579/

Bell LR, McNicol AJ, McNeil E, Van Nguyen H, Hunter JR, O’Brien BJ. The impact of progressive overload on the proportion and frequency of positive cardio-respiratory fitness responders. J Sci Med Sport. 2023;26(10):561-563. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2023.08.175 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37643931/

Taylor NF, Dodd KJ, Damiano DL. Progressive resistance exercise in physical therapy: a summary of systematic reviews. Phys Ther. 2005;85(11):1208-1223. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16253049/

Hollings M, Mavros Y, Freeston J, Fiatarone Singh M. The effect of progressive resistance training on aerobic fitness and strength in adults with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(12):1242-1259. doi:10.1177/2047487317713329 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578612/

Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive endurance exercise training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):869-877. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2012.06.028 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23194487/

Plotkin D, Coleman M, Van Every D, et al. Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ. 2022;10:e14142. Published 2022 Sep 30. doi:10.7717/peerj.14142 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36199287/

McNicol AJ, O’Brien BJ, Paton CD, Knez WL. The effects of increased absolute training intensity on adaptations to endurance exercise training. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(4):485-489. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2008.03.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18762454/

Lorenz D, Morrison S. CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(6):734-747. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4637911/

Mann JB, Thyfault JP, Ivey PA, Sayers SP. The effect of autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise vs. linear periodization on strength improvement in college athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(7):1718-1723. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181def4a6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20543732/

Greig L, Stephens Hemingway BH, Aspe RR, Cooper K, Comfort P, Swinton PA. Autoregulation in Resistance Training: Addressing the Inconsistencies. Sports Med. 2020;50(11):1873-1887. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01330-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32813181/

Hartmann H, Wirth K, Keiner M, Mickel C, Sander A, Szilvas E. Short-term Periodization Models: Effects on Strength and Speed-strength Performance. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1373-1386. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0355-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26133514/

Kildow AR, Wright G, Reh RM, Jaime S, Doberstein S. Can Monitoring Training Load Deter Performance Drop-off During Off-season Training in Division III American Football Players?. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(7):1745-1754. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003149 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31145385/

González-Ravé JM, González-Mohino F, Rodrigo-Carranza V, Pyne DB. Reverse Periodization for Improving Sports Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):56. Published 2022 Apr 21. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00445-8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35445953/

Moesgaard L, Beck MM, Christiansen L, Aagaard P, Lundbye-Jensen J. Effects of Periodization on Strength and Muscle Hypertrophy in Volume-Equated Resistance Training Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(7):1647-1666. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01636-1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35044672/

Williams TD, Tolusso DV, Fedewa MV, Esco MR. Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(10):2083-2100. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0734-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28497285/

Miranda F, Simão R, Rhea M, et al. Effects of linear vs. daily undulatory periodized resistance training on maximal and submaximal strength gains. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(7):1824-1830. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e7ff75 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21499134/

Monteiro AG, Aoki MS, Evangelista AL, et al. Nonlinear periodization maximizes strength gains in split resistance training routines. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(4):1321-1326. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a00f96 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19528843/

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of linear and undulating periodized resistance training programs on muscular strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):1113-1125. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000712 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25268290/

De Souza EO, Tricoli V, Rauch J, et al. Different Patterns in Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations in Untrained Individuals Undergoing Nonperiodized and Periodized Strength Regimens. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1238-1244. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002482 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29683914/

Bartolomei S, Zaniboni F, Verzieri N, Hoffman JR. New Perspectives in Resistance Training Periodization: Mixed Session vs. Block Periodized Programs in Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2023;37(3):537-545. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004465 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36727999/

Bartolomei S, Hoffman JR, Merni F, Stout JR. A comparison of traditional and block periodized strength training programs in trained athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(4):990-997. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000366 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24476775/

Evans JW. Periodized Resistance Training for Enhancing Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength: A Mini-Review. Front Physiol. 2019;10:13. Published 2019 Jan 23. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00013 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30728780/

Fleck SJ. Non-linear periodization for general fitness & athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2011;29A:41-45. doi:10.2478/v10078-011-0057-2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23486658/

Kiely J. Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: evidence-led or tradition-driven?. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7(3):242-250. doi:10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22356774/

Kiely J. Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):753-764. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0823-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29189930/

Mujika I, Halson S, Burke LM, Balagué G, Farrow D. An Integrated, Multifactorial Approach to Periodization for Optimal Performance in Individual and Team Sports. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(5):538-561. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0093 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29848161/

Issurin VB. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports Med. 2010;40(3):189-206. doi:10.2165/11319770-000000000-00000 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20199119/

Issurin V. Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(1):65-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18212712/

Issurin VB. Benefits and Limitations of Block Periodized Training Approaches to Athletes’ Preparation: A Review. Sports Med. 2016;46(3):329-338. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0425-5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26573916/

Cunanan AJ, DeWeese BH, Wagle JP, et al. The General Adaptation Syndrome: A Foundation for the Concept of Periodization. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):787-797. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0855-3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29307100/

Buckner SL, Mouser JG, Dankel SJ, Jessee MB, Mattocks KT, Loenneke JP. The General Adaptation Syndrome: Potential misapplications to resistance exercise. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(11):1015-1017. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.02.012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28377133/

Fisher JP, Csapo R. Periodization and Programming in Sports. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(2):13. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.3390/sports9020013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7909405/

Larsen S, Kristiansen E, van den Tillaar R. Effects of subjective and objective autoregulation methods for intensity and volume on enhancing maximal strength during resistance-training interventions: a systematic review. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10663. Published 2021 Jan 12. doi:10.7717/peerj.10663 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33520457/

Hickmott LM, Chilibeck PD, Shaw KA, Butcher SJ. The Effect of Load and Volume Autoregulation on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):9. Published 2022 Jan 15. doi:10.1186/s40798-021-00404-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35038063/

Vann CG, Haun CT, Osburn SC, et al. Molecular Differences in Skeletal Muscle After 1 Week of Active vs. Passive Recovery From High-Volume Resistance Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(8):2102-2113. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004071 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34138821/

Alves RC, Prestes J, Enes A, et al. Training Programs Designed for Muscle Hypertrophy in Bodybuilders: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(11):149. Published 2020 Nov 18. doi:10.3390/sports8110149 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7698840/