Why is dietary freedom so hard?

“Just eat intuitively.”

“Everything in moderation.”

Those phrases are everywhere. They sound liberating, almost like a finish line. After years of tracking, measuring, or following rules, the promise of effortless dietary freedom is intoxicating: no more diets, no more restriction, just trust yourself.

But for many people, what’s supposed to feel empowering ends up feeling unsettling.

I’ve seen this play out more times than I can count. I distinctly remember one client who came to me after years of rigid meal plans. Every calorie was accounted for, every portion weighed, every “bad” food off-limits. She was tired of it. She wanted a normal relationship with food, something more flexible. So we took the rules away. We gave her permission to eat what she wanted, when she wanted, with the knowledge she already had about balanced nutrition and her body’s signals. Two weeks later, she sat down across from me and said, “I feel more stressed now than I did when I was dieting.”

That experience really stuck with me. I realised that freedom around food sounds like the goal, but for many people, it brings a kind of stress they didn’t expect. When rules disappear, possibility expands… and with it, so does uncertainty.

Every meal turns into a negotiation with yourself: What do I want? Should I have it? How much? Will I regret it later? Is this what a “healthy” person would do? That constant stream of decisions can feel exhausting, especially when the rest of life is already demanding.

This tension isn’t unique to food. Philosophers have been discussing it for centuries. Jean-Paul Sartre, in Being and Nothingness, wrote that “man is condemned to be free”, meaning that the very act of being free comes with responsibility, and responsibility often comes with anxiety. Søren Kierkegaard described it as the “dizziness of freedom,” that unsettling feeling when you realise there’s no script to follow, and no external authority to hand you the “right” answer.

That same dizziness shows up with the diet every day. It’s not really about food; it’s about what happens when no one tells you what to do.

Strict food rules, for all their downsides, offer something seductive: certainty. They remove the burden of choice. No sugar, no carbs after six, only clean foods, etc., these rules give you a sense of safety. They make decisions black and white. And when you’re tired or stressed or stretched thin, that simplicity feels safe.

Freedom, by contrast, asks more of you. It requires attention, self-awareness, emotional regulation, and the courage to live in grey zones.

This is why so many people feel anxious when they “let go of the rules”. It’s not that they lack willpower or discipline. It’s that freedom itself is hard. It’s cognitively and emotionally demanding. And most of us were taught how to follow plans, not how to navigate freedom.

That’s exactly what this article is about. So, if you’ve ever felt like you “should” be able to just eat intuitively but instead end up overwhelmed, there’s nothing wrong with you. You’re dealing with something deeply human; the universal craving for certainty (and the equally universal truth that real growth happens through uncertainty, but we will get to that!).

In the sections ahead, we’ll explore why too much choice can feel paralysing, why black-and-white rules often feel safer, and how to build the skills that make true freedom possible.

TL;DR

Dietary freedom sounds like the dream for many. No more rules, no more tracking, just trust yourself. But when the structure disappears, most people discover something they weren’t prepared for: freedom can feel harder than restriction. When every choice is yours to make, anxiety often takes the place of clarity.

Strict rules, for all their downsides, give us certainty. They’re psychological scaffolding; a way to quiet the noise and make life simpler. Take them away, and you face the dizzying openness Sartre and Kierkegaard wrote about: infinite possibilities and no guaranteed right answer. In today’s world of hyper-palatable food, endless advice, and constant exposure, that can feel like too much.

The problem isn’t a lack of willpower; it’s that freedom requires skills. Real freedom is built, and shouldn’t be thought of as a given. It comes from learning to trust your internal cues, tolerate imperfection, make choices in grey zones, and hold discomfort without running back to the safety of rules. As those skills grow, the anxiety around food loses its grip.

This is where the real transformation happens. Individuals who learn to tolerate freedom don’t just eat differently, they actually live differently. Their confidence expands. Their shame reduces. They become less fragile in the face of uncertainty. And they start to realise that rules were never the enemy. They were just training wheels.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 Freedom vs. Rules: A Psychological Tension

- 3 The Anxiety of Freedom

- 4 The Paradox of Choice

- 5 Why Black-and-White Thinking Feels Easier

- 6 Dietary Freedom Requires Skills, Not Just Good Intentions

- 7 How This Fits Into Modern Life

- 8 Navigating the Fear of Dietary Freedom

- 9 Practical Strategies

- 10 Empowerment Through Tolerating Freedom

- 11 Why Is Dietary Freedom So Hard? Conclusion: Identifying the Fear Dissolves Its Power

- 12 Author

Freedom vs. Rules: A Psychological Tension

When we talk about “freedom” in nutrition and lifestyle, what most people think of is eating what you want, when you want, guided by internal cues rather than strict external rules. This can sound like the ultimate goal.

But what I’ve learned from years of coaching real people: freedom is psychologically harder than rules.

This is not because freedom is negative, it’s because rules do something sneaky in the background that most people don’t realise.

They remove the burden of choice.

Think about a common diet rule: “I don’t eat sugar.” On the surface, it’s restrictive. But psychologically, it’s a shortcut. It removes an entire category of daily decisions. When faced with a plate of cookies at the office, there’s no mental tug-of-war because the rule decides for you. In a world where we’re already making hundreds of micro-decisions every day, that kind of simplicity can feel like relief. Rules may not always be nutritionally optimal, but they often feel emotionally safer.

I’ve watched countless clients breathe easier when they have clear rules to follow. This is not because they love restriction, it’s because rules act like scaffolding. They give shape to something messy and overwhelming, and for a while, that can make everything feel more manageable.

But there’s a trade-off. Freedom requires something that rules don’t: active engagement.

Instead of leaning on black-and-white instructions (“yes” foods, “no” foods, fixed meal times, or whatever your rules of choice are) you have to think, feel, and choose in the grey zones. You have to ask, “What do I actually want right now?” or “What would support my goals and also feel satisfying?” That means tuning in to your internal signals, balancing them with practical knowledge, and managing the discomfort that comes with not having a perfectly “right” answer.

That kind of ongoing, nuanced decision-making takes a lot of work.

This is where Cognitive Load Theory is important to understand. Our brains have limited capacity for processing information at any given time. The more options we face, and the less structure we have to organise those options, the more mental effort it takes to make a choice.

And with food, the options are endless. Walk into any supermarket or scroll through social media, and you’ll face thousands of competing messages about what you should eat, what you shouldn’t eat, and what some influencer swears will “fix everything”.

Every choice pulls on your mental bandwidth.

Layer on top of that the concept of decision fatigue, which is the idea that the more decisions you make throughout the day, the harder each subsequent one becomes. By the time you get home from work, after making dozens (or hundreds) of small decisions, your mental fuel tank feels low. That’s often the moment clients tell me they “gave in” to cravings or “fell off the plan.” It’s not that they suddenly lost discipline, it’s that they ran out of decision-making energy.

This is why strict rules can feel like a relief. If the decision is already made by the rule (no sugar, no snacks after dinner, only one glass of wine or whatever) then you’re not spending precious cognitive energy wrestling with it. And if the rest of your life is demanding (which it usually is), this can feel like the only way to keep things manageable.

But many people don’t consciously recognise this psychological tension. They think they like rules because they’re “good at following plans” or “need discipline.” In reality, they’re responding to something more universal which is the human desire for security and structure in the face of overwhelming choice.

People with a more external locus of control (meaning they tend to rely on external structures, authority, or rules to guide behaviour) often feel especially anchored by rigid plans. The rules become a kind of safety net. Autonomy, on the other hand, can feel like being pushed out into deep water without a life jacket. But this is not a personal flaw. It’s a predictable, human response to uncertainty.

I often use this metaphor with clients: freedom without skill is like giving a sports car to a new driver. Without training, that kind of power isn’t exhilarating, it’s terrifying. You can stall out, overcorrect, spin out of control or crash. But with practice and skill, the same car becomes something entirely different.

Nutrition works the same way. Rules are the training wheels. They provide temporary structure that helps keep you upright. But to move toward real, lasting freedom, you eventually need to develop the skills to balance for yourself. That means learning to tolerate ambiguity, trust your internal signals, and build confidence in your decision-making.

Recognising this psychological tension is the first step. It’s not about glorifying rules or rejecting them outright. It’s about understanding why they feel safe and preparing to build the skills that make freedom feel safe too.

The Anxiety of Freedom

The moment you remove rigid rules and have to deal with full autonomy, you touch up against something that philosophers have wrestled with for centuries: freedom itself can make us anxious.

This isn’t just a modern wellness issue; it’s a deeply existential one.

Jean-Paul Sartre famously wrote, “Man is condemned to be free.” His point wasn’t that freedom is bad, it’s that once we have it, we can’t escape the responsibility it brings. No one tells us what to choose. No one guarantees the outcome. Every decision is ours to own. That’s empowering… and hard.

Søren Kierkegaard captured the feeling perfectly when he described “the dizziness of freedom.” It’s like standing at the edge of an open cliff, staring at endless possibilities. You could step in any direction, but that very openness can make your stomach drop. Friedrich Nietzsche took it further: “Become who you are.” Freedom, to him, wasn’t just about choosing, it was about writing your own story when no script exists. And Michel Foucault offered a practical counterpoint: we often build technologies of the self like structures, habits, and yes, rules, to help us manage that chaos and feel safe.

You can see this dynamic play out in something as ordinary as deciding what to eat. When everything is technically “allowed,” the internal monologue can get loud fast:

“If I can choose anything, what should I choose?”

“What’s the right decision here?”

“What if I pick wrong and undo my progress?”

It’s rarely about the cookie or the salad. It’s about the weight of responsibility that comes with making the decision yourself.

I’ve worked with countless clients who are brilliant, capable people in every other part of their lives, but the moment they’re handed full freedom with food, they freeze. They know what healthy choices are, but freedom exposes uncertainty. There’s no longer a rule to hide behind and no plan to blame or praise. It’s just them, making the call.

When uncertainty feels too challenging, the natural response is to retreat into rules. I’ve seen people go back to strict meal plans, rigid fasting windows, or black-and-white “good” and “bad” food lists. They know these systems aren’t perfect, but they provide a kind of existential relief. It’s easier to follow a plan than to face the discomfort of infinite choice.

That pressure to “get it right” is powerful. Most people often won’t say it outright, but it does show up in subtle ways:

- Fear of making the wrong choice. “If I eat this, does it mean I’ve failed?”

- Perfectionism in disguise. “I have to eat perfectly or it’s not worth it.”

- Avoidance. “If I stick to the rules, at least I can’t mess it up.”

What they’re actually wrestling with isn’t just a nutrition strategy, it’s the same human tension Sartre, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Foucault were talking about. The anxiety of freedom. The pull between wanting autonomy and fearing what it demands. There is a cost to being free.

In the context of the diet, this is one of the most important dynamics to actually identify. Because when you believe your struggle is simply “not having enough discipline,” you’re fighting the wrong battle. What you’re really up against is the discomfort of freedom itself. And that’s something you can actually work with, not something to be ashamed of.

Rules aren’t just dietary guardrails, they’re often psychological coping tools, a way of bringing order to chaos. But true growth happens when you can hold that freedom without collapsing under it.

This is where nutrition stops being about calories and macros and becomes something much deeper; an actual reflection of what it means to be human in a world where the menu, quite literally, is endless.

The Paradox of Choice

We love the idea of choice. The more options we have, the more free and empowered we think we’ll feel. But in practice, the opposite often happens.

More options don’t always make us happier, they often make us more stressed, less decisive, and less satisfied with what we choose.

This is what psychologists call the paradox of choice. When possibilities expand, decision-making gets harder. You can see this play out in nutrition every single day.

Take something as simple as a restaurant menu. If there are three options, it’s fairly easy to pick one and move on. You choose, you eat, you enjoy. But if the menu is ten pages long with thirty different entrees, each with endless “build your own” customisations, your brain starts to short-circuit. You weigh every possibility, wonder if you’re missing out on the best one, and second-guess your choice the minute the plate hits the table.

The same thing happens in grocery stores. A century ago, people chose between a handful of basic staples. Now, a single aisle might have fifty kinds of yogurt or hundreds of different cereals. Do you want the high-protein one? Low sugar? Plant-based? And before you know it, a quick stop for shopping has turned into a full-on mental marathon.

And then there’s the nutrition advice itself. If you’ve ever Googled “best diet for weight loss” or “how to eat healthy,” you’ve seen the chaos. Paleo, keto, Mediterranean, intermittent fasting, plant-based, carnivore, intuitive eating, macro tracking, clean eating… the list goes on. Each one has its rules, advocates, critics, and testimonials promising results. For many people, the sheer volume of options leads to paralysis. Instead of feeling empowered, they feel stuck, overwhelmed, and unsure where to even begin.

This is where psychology helps us make sense of what’s happening. Cognitive load capacity isn’t infinite. Every extra choice increases the demand on that system. When the options pile up, we hit a kind of cognitive overload. And that’s when decision fatigue sets in. The more decisions you make throughout the day, food-related or otherwise, the less energy you feel like you have left to make good ones.

You’ve probably felt this before: after a long, busy day, even small choices can feel monumental. You might end up procrastinating (“I’ll figure out dinner later”), defaulting to autopilot (“I’ll just get takeout again”), or overthinking everything until you’re too drained to decide at all. Some people end up eating impulsively; others end up not eating enough. It’s not a lack of discipline — it’s the predictable cost of too many choices.

And even when you do make a decision, more options can actually make you less satisfied with it. When there were only three things to choose from, picking one feels straightforward. But when there were thirty, your brain can’t help but wonder if you chose wrong. “Maybe I should’ve gone with the salmon.” “What if the other plan would’ve worked better?” This regret and second-guessing quietly erode your confidence, making future choices even harder.

Many people have low tolerance for ambiguity (your ability to function well when there isn’t a single “right” answer) around food. They want certainty: “this is the best diet,” “this is the right choice.” But nutrition, like most things in life, rarely works in absolutes. It’s a world of grey zones, and for some, living in that grey is deeply uncomfortable. So they either cling to rigid rules or avoid making decisions altogether.

Choice is a privilege and a powerful tool when managed well. But the paradox of choice reminds us that freedom without boundaries can become its own source of stress. As a coach, I’ve seen over and over again that most people don’t thrive with unlimited possibilities. They thrive with structured flexibility: enough choice to feel free, but enough rules/constraints to feel secure.

So if you’ve ever felt anxious staring at a menu, overwhelmed in the grocery aisle, or stuck trying to pick the “right” way to eat, you’re experiencing what happens to almost everyone when the sheer volume of choice outweighs our capacity to hold it. But there are answers here, and ways to navigate this (which we will get to).

Why Black-and-White Thinking Feels Easier

If there’s one pattern I’ve seen again and again in my coaching, it’s that black-and-white rules feel easier than living in the grey. When people say things like “No carbs after 6 p.m.,” “I don’t eat sugar,” or “I only eat clean foods,” it might sound rigid, but underneath, I know this is less about the specific rules, and more about the fact that people find certainty comforting.

When something is clearly “off-limits,” you don’t have to negotiate with yourself. There’s no inner debate at 8:30 p.m. about whether or not to have a bowl of cereal or whether dessert “fits” your plan. The rule makes the decision for you. In a world where our brains are already managing work deadlines, family schedules, financial stress, social pressures, and constant notifications, removing one more decision can feel like relief.

This is where black-and-white thinking slips in and takes hold. It simplifies a complex reality into something neat and manageable. Instead of asking, “How hungry am I? What do I want? How does this fit into the bigger picture?” you just say, “This is allowed; this isn’t.” That may not sound like a big deal, but psychologically, it can dramatically reduce your cognitive load.

This is one of the reasons why strict diets can feel so comforting in the short term. They provide a clear structure, and structure, even when it’s restrictive, can make life feel more predictable and controllable. For someone who’s already juggling a lot, that sense of order can feel safer than the open-ended uncertainty of “moderation” or intuitive eating.

This is also why I tell clients that clinging to rules isn’t necessarily a sign of weakness. More often, it’s a coping mechanism. It’s a way to find stability in an environment that’s full of uncertainty and noise. You have to remember that you are navigating an environment that we did not evolve for, and is stacked against us. Constant food marketing, endless opinions online, social pressure, conflicting advice, and countless other pulls on us. In that context, rules are a psychological anchor.

Let’s be honest here, black-and-white rules make it super easy for you to feel like you’re “doing it right.” They create clean lines between success and failure, good and bad, on track or off track. If you stick to the rule, you get the gold star. If you break it, you don’t. That simplicity is seductive because it offers emotional clarity, even if it’s artificial.

Of course, the flip side is that this clarity often comes at a cost. When reality doesn’t fit neatly into the rules (like when life throws a curveball, when you want flexibility, or when the “perfect plan” collides with real-world imperfection), those rigid lines can become prison bars. But at least at first, the clarity does feel like safety.

That’s the key point here: constraint isn’t always the enemy. Rules can act as scaffolding that helps you feel supported while you build the skills to handle more flexibility later. Rules can be a stabiliser, a training ground. They can give someone who’s overwhelmed by the abundance of choice a foothold to grow.

So, when I am working with someone on their nutrition, we aren’t looking to rip all dietary rules away overnight. It’s often about understanding why they feel safe, and then teaching clients how to gradually step into more nuanced decision-making without losing that sense of security. It’s not about demonising black-and-white thinking, it’s about eventually learning to live comfortably in the grey.

Dietary Freedom Requires Skills, Not Just Good Intentions

When people talk about “dietary freedom,” it often gets framed as this magical destination; the day when you can just trust yourself and everything falls into place. But in reality, true dietary freedom isn’t about winging it. It’s not the absence of structure or effort. It’s the result of developing a set of skills that allow you to function confidently without a rigid rulebook.

This is where many people get stuck. They think if they just “try harder,” they’ll be able to eat intuitively. But trying harder isn’t a strategy. Freedom without skills is just chaos.

To handle freedom well, you need a foundation, not just good intentions. (I discuss this a lot more in the article on intentional eating)

The first of those skills is self-awareness and emotional literacy. Most people eat for a mix of reasons such as hunger, habit, stress, social connection, emotion, and convenience. If you can’t tell the difference between physical hunger and emotional urges, dietary freedom gets confusing fast. Building this awareness means learning to tune in to your body’s cues, and involves noticing patterns, understanding triggers, and separating short-term impulses from true needs.

The second piece is trusting your internal cues. This doesn’t happen overnight. If you’ve spent years outsourcing decisions to diets, plans, or tracking apps, it can take time to rebuild that trust. At first, it might even feel unreliable, like driving without GPS after years of relying on turn-by-turn directions. But with practice, your internal signals get louder and clearer.

Third, understanding the fundamentals of nutrition matters more than most people realise. Intuitive eating isn’t about ignoring science; it’s about integrating it (this is why I prefer intentional eating). Knowing how protein supports satiety, how fibre affects digestion, how energy balance works, or how different foods impact your training or mood gives you the confidence to make flexible choices without second-guessing everything.

And then there’s the psychological side you will have to master, too. You will need to learn to tolerate uncertainty and imperfection. Freedom means living in the grey zone. You won’t always get it “perfect.” Sometimes you’ll overeat. Sometimes you’ll underfuel. Sometimes your food choices won’t be what you planned. That’s not failure, that’s normal human life. One of the most important things I help clients develop is the ability to feel discomfort without collapsing back into rigid rules.

This ties closely to what Self-Determination Theory in psychology tells us: autonomy without competence or support often leads to overwhelm, not empowerment. If someone is given freedom but hasn’t developed the skills to manage it, they feel lost, not liberated. It’s the equivalent of taking the training wheels off a bike before the rider knows how to balance.

Tolerance of ambiguity is another underrated skill here. The more someone can function well without needing perfect answers, the more capable they become in flexible environments. Tolerance of ambiguity isn’t a fixed attribute, and it can be developed through gradual exposure and skill-building. I’ve seen people go from needing a perfectly defined meal plan to confidently making flexible choices at a buffet. It doesn’t happen by accident though, you do actually have to build the skill (which means mistakes and slip-ups will be made!).

That’s why this transition has to be gradual for most people. Most people have never had to navigate this level of autonomy before, so their skills need to be built slowly. For years, their eating has been governed by external systems like diets, calorie targets, macro splits, “good” and “bad” food lists. Those systems acted as scaffolding. Once they’re removed, many people don’t yet have the psychological structure to stand without them.

But the good news is that those skills can be learned. Trust can be rebuilt. An internal locus of control (the belief that you can guide your own choices) can be cultivated over time with coaching, reflection, and practice.

I often use what I call the “Freedom Tolerance Curve” to explain this. On one end, there’s too little freedom: rigid, rule-bound eating that feels safe but suffocating. On the other end, there’s too much freedom: chaos, overwhelm, decision fatigue. Somewhere in the middle is the sweet spot (structured flexibility) where you have enough support to feel secure but enough autonomy to feel empowered. That’s where real food freedom lives.

So no, freedom isn’t about letting go and hoping for the best. It’s about building the skills that make freedom feel safe, sustainable, and yours. This is the work that turns “I hope I can handle it” into “I trust myself to handle it.”

How This Fits Into Modern Life

To really understand why freedom around food can feel so overwhelming, it helps to zoom out and look at the bigger picture: our modern environment is radically different from the one humans evolved in.

For most of human history, food choices were incredibly limited. People ate what was available locally and seasonally. There weren’t 12 different kinds of bread at the supermarket or 40 snack options in your cupboard. Meals were shaped by geography, climate, and culture, and they didn’t require endless decision-making. This scarcity meant that choice wasn’t something you had to wrestle with every day.

Fast-forward to today, and the situation is the complete opposite. We live in a world of abundance and constant exposure. Food isn’t just available, it’s engineered to grab your attention. Supermarkets line every aisle with hyper-palatable options carefully designed to keep you coming back for more. Fast food, takeout, snacks, delivery apps, energy drinks, protein bars, speciality diets, influencers, and conflicting “expert” advice… it’s relentless.

Even when you’re not eating, you’re surrounded by food marketing. Billboards, TV ads, packaging, notifications, “what I eat in a day” videos. This constant exposure isn’t neutral, it primes your brain to make decisions, often in the direction of convenience, immediate gratification, or whatever’s being sold the loudest. If you don’t believe this, then you have to make a strong argument for why all of these food companies spend billions of dollars on advertising then. If it didn’t work, they wouldn’t waste their money (or at least not so much of it).

This dynamic isn’t unique to food. It mirrors what’s happening across modern life. Think about careers as another example. Once, there were a handful of stable, expected paths; now there are infinite possibilities. The same goes for relationships, identity, where to live, how to live, and how to define success. In almost every domain, too many paths can make people feel lost or stuck, not free.

This is why naming the problem matters so much. When someone struggles to navigate food freedom, it’s not just about personal discipline. It’s not because they’re lazy or weak. They’re trying to manage modern abundance with a brain wired for scarcity and simplicity. Acknowledging this doesn’t remove personal agency, but it normalises the struggle and removes the shame. You’re not broken, you’re living in an environment designed to overwhelm your decision-making systems.

Choice is empowering only when the capacity exists to handle it. Freedom isn’t just about having options, it’s about having the skills, the structure, and the energy to navigate them well. If capacity and environment are out of balance, even “healthy” freedom can turn into frustration or self-blame.

This leads to some of the biggest emerging debates in nutrition today. One is about the limits of intuitive eating in a hyper-palatable food environment. Intuitive eating was developed with good intentions and sound principles (trusting your internal signals and listening to your body), but when the world around you is engineered to override those signals, that trust can be easily hijacked. It’s not that intuitive eating doesn’t work, but that it doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Another key debate this intersects with is the tension between personal responsibility and the systemic food environment. On one hand, we can empower individuals with knowledge, skills, and strategies. On the other, we can’t ignore the massive influence of food systems, marketing, accessibility, socioeconomic factors, and cultural pressures. Asking individuals to “just make better choices” without acknowledging the weight of the environment is like asking someone to run uphill with a backpack full of rocks. Some are strong enough to do it, some aren’t. But it would be much easier for everyone if we didn’t have to carry the rocks.

This is why a compassionate, realistic approach to food freedom matters. It’s not about moralising choice or pretending we live in a neutral world. It’s about recognising the landscape for what it is, abundant, loud, and overwhelming. As a result, a core coaching goal I have with my clients is to equip them with the tools and support to navigate nutrition on their own terms.

Because freedom in this environment isn’t just handed to you. It’s something you build, skill by skill, anchor by anchor, until the noise of modern abundance doesn’t drown out your own voice.

One of the most important parts of helping someone truly thrive with food freedom isn’t just about teaching nutrition science or building habits, it’s about navigating the fear that comes with autonomy. Most people assume freedom should feel good. But when that freedom shows up as uncertainty, anxiety, or pressure to “get it right,” they blame themselves.

What they’re feeling isn’t personal failure, it’s a normal human response to choice. So the way forward isn’t to ignore that fear or push through it with willpower. It’s to work with it systematically, step by step.

Step 1: Naming the dynamic

The first step is simply recognising what’s happening. For many individuals, just naming the fact that dietary freedom can create anxiety is a massive relief. They stop thinking, “Something’s wrong with me,” and start understanding, “Oh, this is a normal part of the process.”

When people go from structured diets to open-ended eating, their internal alarm system often activates, because they’ve lost their old sense of certainty. By identifying this anxiety for what it is (i.e. not a character flaw), you remove a big layer of shame. Awareness itself is powerful: it turns an invisible weight into something that can be worked with.

Step 2: Reframing rules

The next step is to reframe the role of rules. In a lot of nutrition spaces, rules are either glorified or vilified, but in truth, rules are often just coping tools. They’re a way of managing uncertainty and maintaining a sense of control in a noisy environment.

This means rules don’t need to be thrown away overnight. We can view them as temporary scaffolding. Structures that can evolve over time. For example, instead of “I never eat after 6 p.m.,” the guideline might become “I usually finish eating early, but I can make exceptions when it makes sense.”

This gradual shift from rigid rules to flexible guidelines allows people to loosen their grip without falling into chaos. It’s not about abandoning all structure; it’s about reshaping it into something that serves you, not controls you.

Step 3: Building trust and capacity

Freedom isn’t something you wake up with; it’s something you build through experience. This is why gradual exposure matters so much.

If someone’s been living in black-and-white nutrition rules for years, jumping straight into total autonomy is like jumping from the frying pan right into the fire. Instead, we introduce manageable grey zones. This can be done in situations where they have room to practice decision-making with support, not judgment. The stakes should be low, and mistakes and slip ups should be seen as part of the process.

For example: planning a flexible meal at a restaurant without overanalysing it. Allowing a favourite food into the house without labelling it as “good” or “bad.” Eating in response to hunger rather than the clock.

This is where self-trust and resilience are built. You don’t always have to make the “perfect” choice, you can learn to trust yourself to make good choices, even when things can’t go perfectly. Good enough is the goal, not perfection.

Step 4: Supporting emotional safety

The fear of freedom isn’t just intellectual; it’s emotional. It can bring up shame, guilt, or even panic. So part of the work is creating emotional safety around the process.

This means validating the discomfort instead of pathologising it. Saying things like, “Of course this feels hard, it makes sense why I find this challenging,” is often more powerful than a dozen nutrition lectures. It’s helping someone hold that discomfort without running back to rigid rules for relief.

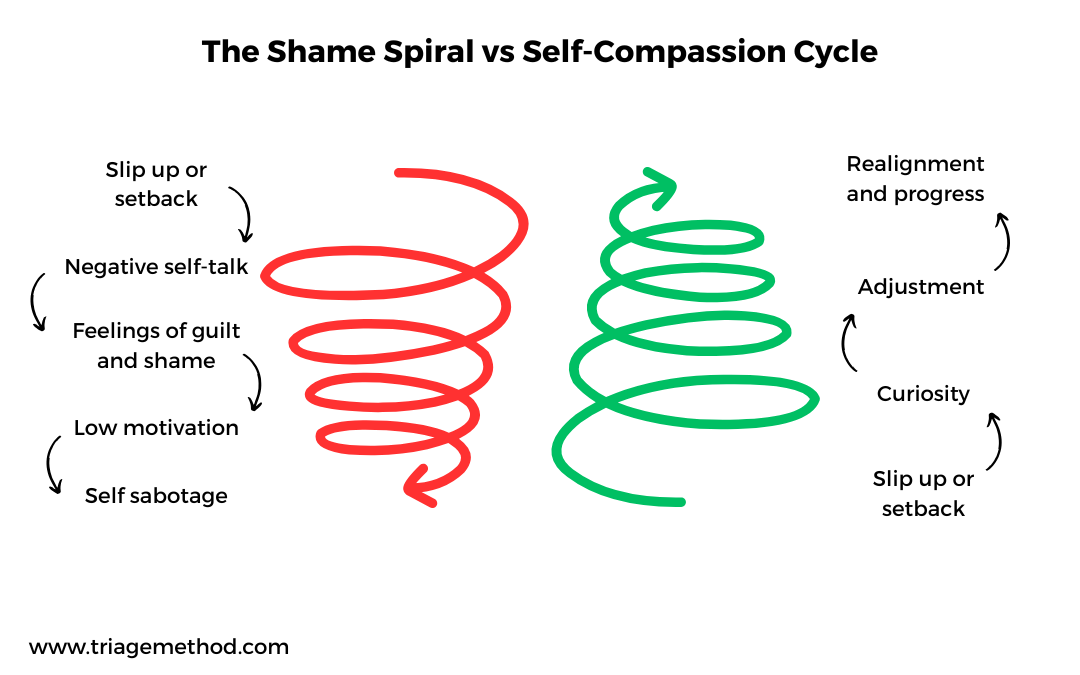

This also means dismantling the shame that often shows up when someone “slips.” Struggling with freedom is part of what it means to be human. But shame pushes people back into hiding, whereas normalising it keeps them growing in the direction we want.

Ultimately, if you’ve ever felt anxious when faced with more food freedom, that doesn’t mean you’re broken. It means you’re navigating a universal human experience: the tension between structure and autonomy.

Freedom isn’t just about having choices, it’s about being able to navigate those choices in alignment with your goals and values. The capacity to do that is built, step by step, with compassion, practice, and support.

You must recognise your anxiety for what it is, simply a sign that you’re growing into a new skill.

Practical Strategies

Dietary freedom isn’t something that just clicks into place one day. It’s something that gets built intentionally, gradually, and with a clear strategy. When people hear the phrase “dietary freedom,” they often picture letting go of rules entirely and just knowing what to do. But in real life, that approach usually leads to overwhelm. What actually works is what I call structured flexibility: a balance of freedom and support that makes choices feel manageable instead of chaotic.

The first piece of this is narrowing the field. When you have too many options, decisions become exhausting. But when you have none (when everything is rigid), you lose joy and autonomy. The sweet spot is somewhere in between: a smaller set of flexible choices that create ease without trapping you. Think of it like building a personal menu you can live with. A few planned treats instead of an open-ended “eat whatever.” A handful of balanced guidelines, like aiming for protein and veggies at most meals, instead of hard rules. A curated list of go-to breakfasts or reliable takeout orders instead of a mental war every time you’re hungry. This isn’t about creating arbitrary restrictions, it’s about creating clarity within your decision space.

Another practical piece is creating decision-making scaffolds that make daily choices less mentally draining. This can mean having a few default meals on standby so you’re not starting from scratch every time, or following simple principles that guide you without boxing you in. It can also mean embracing “good enough” choices, such as learning to see a reasonably balanced meal as a win, rather than falling into the trap of perfectionism. These small anchors reduce cognitive load and preserve mental energy for the decisions that actually matter.

Of course, even with structure, there will be moments of discomfort. Real freedom means facing uncertainty. You will have to tackle those moments of doubt, guilt, or second-guessing that used to be covered up by strict rules. This is where mindfulness and body awareness come in, not in a fluffy, abstract way, but in the very practical sense of paying attention to your hunger, fullness, and emotional state without immediately reacting. It means noticing what’s going on inside you and making a conscious choice instead of defaulting to old patterns. Discomfort doesn’t have to be a red flag. Often, it’s a sign that you’re doing the real work of growth.

Progress here isn’t just about what you eat. It’s about how you handle the grey areas. The small wins matter. The night you didn’t spiral after an unplanned dessert, the meal you chose without overanalysing, the moment you trusted yourself a little more. These are the true markers of someone building capacity, not just following a plan.

This process isn’t just psychological though, it’s biological. Your prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function, handles flexible decision-making. It can get overloaded, which is why structure helps conserve energy. Meanwhile, your habit systems, rooted in the basal ganglia, gradually automate these new patterns. Over time, through repetition and neuroplasticity, your brain gets better at navigating uncertainty. Freedom becomes easier because you’ve trained for it.

So, if freedom feels hard, it’s not a personal failing, it’s a signal that you need more structure to support it. Start small. Create anchors. Give yourself guardrails that allow for movement without overwhelm. Then, like strength training, slowly build your tolerance for ambiguity through consistent practice. Real food freedom isn’t about having no structure at all; it’s about building just enough structure to trust yourself when the rules are gone.

Empowerment Through Tolerating Freedom

The real win in this whole process isn’t about reaching a point where food never makes you anxious again. That’s a myth. Even people who have a deeply peaceful relationship with food still feel moments of uncertainty. Standing in front of a menu they didn’t plan for, navigating an unfamiliar social situation, or having an off day where hunger signals feel murky. True empowerment isn’t about eliminating that fear; it’s about learning to live with it.

Freedom isn’t supposed to be weightless. It carries responsibility, choice, and sometimes discomfort. Empowerment comes from being able to feel that discomfort without letting it control you. It starts with recognising the fear for what it is: a natural human reaction to open decision space. Once it’s named, it can be worked with instead of avoided. That’s the turning point where someone stops feeling like they’re constantly “failing at moderation” and starts understanding that this is simply part of the work.

Then comes the practice of working with that fear instead of against it. Instead of rushing back to the safety of rules every time things feel uncertain, you learn to stay present, make a decision with the information you have, and trust yourself to handle the outcome. Sometimes that decision will be exactly what aligns with your goals. Sometimes it won’t. Either way, your ability to trust your own judgment grows stronger each time.

This is what it looks like to trust yourself without a rulebook. No plan dictating every move. No rigid boundaries to hide behind. Just you, your awareness, your skills, and your values, steering the ship.

Once someone learns to do this with food, it rarely stays limited to food. The ripple effects spread far beyond the plate.

Clients who build this capacity often talk about feeling a new kind of confidence, the kind that comes from knowing, “I can handle this.” Shame starts to fade because the goal is no longer perfection; it’s resilience. Flexibility becomes a strength rather than a threat. They become less reactive to uncertainty in other areas of life because the underlying skill is the same. When you can hold freedom without running from it, everything starts to open up.

This is what Friedrich Nietzsche meant when he wrote, “Become who you are.” Freedom isn’t about a life without rules. It’s about self-authorship and the ability to write your own rules, adjust them as needed, and trust yourself to live by them. In this way, food freedom becomes less about “what to eat” and more about becoming the kind of person who trusts their own choices.

Psychology backs this up. When people build tolerance of ambiguity, their resilience increases, and they stop needing every choice to feel perfect or certain. Their internal locus of control grows, as does their confidence. These aren’t immutable traits, they’re actually trainable skills. And once you have them, they change the way you move through the world.

The deeper win here is the ability to stand in that grey space, make choices that align with who you are, and know that whatever comes next, you can handle it. That’s actual freedom.

Why Is Dietary Freedom So Hard? Conclusion: Identifying the Fear Dissolves Its Power

Freedom, when it comes to food, is both a gift and a burden. It offers the possibility of ease, trust, and flexibility, but it also asks something of us in return. It asks us to stand in uncertainty, to make choices without guarantees, to trust ourselves without someone else’s rulebook. When people first encounter this, it can feel intimidating, even defeating. But identifying the fear is what dissolves its power.

When we acknowledge that the anxiety around food freedom is real, and normal, we strip away the moral weight that so many people carry. It stops being about willpower, discipline, or “getting it together,” and becomes what it actually is: a human challenge. One that can be understood, practised, and overcome.

If you’ve ever felt frustrated by your inability to “just eat intuitively” or to thrive without strict rules, there’s nothing wrong with you. This isn’t a sign of weakness. It’s a sign that you’re a human navigating a complex modern environment with a brain that craves clarity and safety. Once we frame it that way, the shame falls away, and real progress can begin.

Rules themselves aren’t the enemy here. For many people, they’re the training wheels that allow them to find their balance. They give structure when everything feels overwhelming. And like training wheels, they’re not meant to stay forever, but they can be a necessary and helpful part of the process. With time, skill-building, and support, you can learn to ride without them. The fear doesn’t disappear entirely, you just learn to trust your ability to keep moving even when uncertainty presents itself.

That’s the power of identifying what’s really happening. Freedom stops being a vague, intimidating ideal and becomes something concrete, something you can grow into step by step.

And so the question I leave you with is this: Are rules really the opposite of freedom, or are they a stepping stone to it?

If you need more help with your own nutrition, you can always reach out to us and get online coaching, or alternatively, you can interact with our free content, especially our free nutrition content.

If you want more free information on nutrition or training, you can follow us on Instagram, YouTube or listen to the podcast, where we discuss all the little intricacies of exercise and nutrition. You can always stay up to date with our latest content by subscribing to our newsletter.

Finally, if you want to learn how to coach nutrition, then consider our Nutrition Coach Certification course, and if you want to learn to get better at exercise program design, then consider our course on exercise program design. We do have other courses available too. If you don’t understand something, or you just need clarification, you can always reach out to us on Instagram or via email.

References and Further Reading

Markey CH, Strodl E, Aimé A, et al. A survey of eating styles in eight countries: Examining restrained, emotional, intuitive eating and their correlates. Br J Health Psychol. 2023;28(1):136-155. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12616 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10086804/

Hazzard VM, Telke SE, Simone M, Anderson LM, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D. Intuitive eating longitudinally predicts better psychological health and lower use of disordered eating behaviors: findings from EAT 2010-2018. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):287-294. doi:10.1007/s40519-020-00852-4 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32006391/

Gödde JU, Yuan TY, Kakinami L, Cohen TR. Intuitive eating and its association with psychosocial health in adults: A cross-sectional study in a representative Canadian sample. Appetite. 2022;168:105782. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2021.105782 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34740711/

Bayram HM, Gürbüz M. The associations of mindful and intuitive eating with BMI, depression, anxiety and stress across generations: a cross-sectional study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2025;76(3):326-336. doi:10.1080/09637486.2025.2462185 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39910420/

Gao XX, Zheng QX, Chen XQ, et al. Intuitive eating was associated with anxiety, depression, pregnancy weight and blood glucose in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective longitudinal study. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1409025. Published 2024 Jul 25. doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1409025 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39135553/

Janssen LK, Duif I, Speckens AEM, et al. The effects of an 8-week mindful eating intervention on anticipatory reward responses in striatum and midbrain. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1115727. Published 2023 Aug 11. doi:10.3389/fnut.2023.1115727 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10457123/

Burnette CB, Hazzard VM, Larson N, Hahn SL, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Is intuitive eating a privileged approach? Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between food insecurity and intuitive eating. Public Health Nutr. 2023;26(7):1358-1367. doi:10.1017/S1368980023000460 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10346026/

Pignatiello GA, Martin RJ, Hickman RL Jr. Decision fatigue: A conceptual analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):123-135. doi:10.1177/1359105318763510 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29569950/

Moorhouse A. Decision fatigue: less is more when making choices with patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(697):399. Published 2020 Jul 30. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X711989 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7384807/

Açik M, Aslan Çin NN. Links between intuitive and mindful eating and mood: do food intake and exercise mediate this association?. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1458082. Published 2025 May 30. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1458082 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12162310/

Ruiz AC, de Lara Machado W, D’avila HF, Feoli AMP. Intuitive eating in the COVID-19 era: a study with university students in Brazil. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2024;37(1):28. Published 2024 Jul 25. doi:10.1186/s41155-024-00306-1 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11272766/

Erhardt GA. Intuitive eating as a counter-cultural process towards self-actualisation: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of experiences of learning to eat intuitively. Health Psychol Open. 2021;8(1):20551029211000957. Published 2021 Mar 10. doi:10.1177/20551029211000957 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7961715/