I can almost guarantee that if you are a coach for any length of time, you will have gone through something like this. Your client texts you on Monday evening. She missed her morning workout. Her alarm didn’t go off, morning got away from her, it happens. By Wednesday, she’s gone silent. By Friday, you’re looking at read receipts and wondering what happened. When she finally responds the following week, she’s apologetic, embarrassed, and already talking about “starting fresh” as though the previous three months of consistent work have been erased by one missed session.

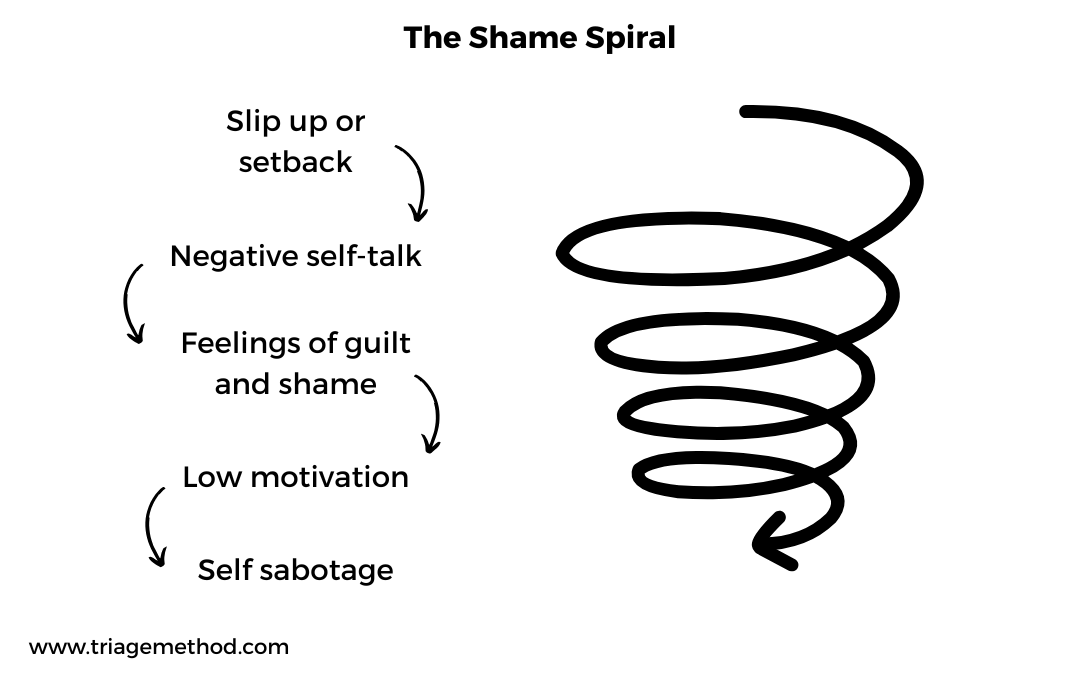

You know this pattern. You’ve seen it dozens of times. The client who’s progressing beautifully until one disruption (a skipped workout, an unexpected night out, a week of poor sleep, or whatever else) sends everything sideways. They don’t just miss one session; they disappear for a fortnight. They don’t just have one meal off plan; they write off the entire weekend. The spiral is so predictable that you can almost set your watch by it.

Unfortunately, more physiology knowledge can’t help you with this. You need to learn psychological principles that actually allow you to help your clients with this stuff. You need to be able to explain why a single missed workout becomes a catastrophe. Yes, you must understand progressive overload, periodisation, energy balance, and protein synthesis. And I am sure you can program a deload, manipulate training variables, and adjust macros. But none of that matters when your client is sitting in their kitchen at 10pm, staring at an empty packet of biscuits, convinced they’ve ruined everything and there’s no point continuing.

However, there’s a tool from clinical psychology that changes how you handle these moments entirely. It comes from Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy, it’s called the ABC model, and most coaches have never heard of it. They spend years learning the minutiae of muscle fibre types and optimal rest periods, which matters for sure, but then they’re completely unprepared for the psychological spirals that actually derail their clients. Learning how to use the ABC model in coaching won’t replace your training knowledge, but it will complete it.

TL;DR

Most coaches lose clients because they can’t help clients handle the psychological spiral that follows a single setback. When someone misses one workout and disappears for two weeks, that’s not a motivation problem, it’s a thinking problem.

The ABC model from Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy gives you a framework to address this. A is the Activating Event (the thing that actually happened), B is the Belief (the interpretation your client assigns to it), and C is the Consequence (the emotional and behavioural result).

The critical insight is that it’s not A causing C, it’s B.

The missed workout is neutral; it becomes catastrophic only through the meaning your client constructs around it.

When you help clients separate events from interpretations, reality-test their catastrophic beliefs, and develop more accurate alternative thoughts, you’re teaching them a transferable skill that transforms how they handle setbacks. This isn’t therapy; it’s legitimate coaching work that addresses the cognitive layer where behaviour change actually happens.

You still need solid physiology knowledge, but understanding how to work with your clients’ thinking is what separates good coaches from excellent ones. The ABC model completes your toolkit by helping you work with the psychology that determines whether your programming actually gets followed.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 The Pattern You’ve Seen a Hundred Times

- 3 How to Use the ABC Model in Coaching: The Framework

- 4 Spotting the ABC Pattern With Your Clients

- 5 What Your Clients Are Really Doing When They Catastrophise

- 6 Applying the ABC Model: Your Practical Process

- 7 Join 1,000+ Coaches

- 8 What to Watch Out For

- 8.1 Pitfall 1: Trying to Skip to D (Disputation) Too Quickly

- 8.2 Pitfall 2: Treating Every Setback as an ABC Problem

- 8.3 Pitfall 3: Becoming Their Therapist

- 8.4 Pitfall 4: Using REBT Language That Sounds Clinical

- 8.5 Pitfall 5: Dismissing Beliefs That Have Some Validity

- 8.6 Pitfall 6: Forgetting That Beliefs Are Often Culturally Shaped

- 9 Beyond the Immediate Crisis

- 10 What This Tool Can’t Do

- 11 Making This Second Nature

- 12 The Real Work of Coaching

- 13 Author

The Pattern You’ve Seen a Hundred Times

Let me describe someone you’re probably working with right now. They show up consistently for eight weeks. They’re doing the work, seeing results, and feeling good about themselves. Then something happens, they travel for work, they get ill, their routine gets disrupted or whatever happens frequently in your client niche. They miss a few sessions. When they return, they’re different. Tentative. Apologetic. They talk about how they “fell off the wagon” or “went off the rails.” They’re already hedging, already preparing you for their inevitable failure.

You try to reassure them. You tell them it’s fine, everyone misses workouts, what matters is getting back to it. They nod, they agree, they say all the right things. Then they ghost you for three weeks.

This isn’t a motivation problem. It’s not a discipline problem. It’s not even, usually, a practical problem. Their schedule hasn’t fundamentally changed, and their circumstances are manageable. It’s a thinking problem. Something happened in their mind between the missed workout and the spiral, and if you can’t work with that cognitive layer, you’re coaching with one hand tied behind your back.

The real skill gap in coaching isn’t your ability to program a conjugate periodisation scheme or calculate someone’s theoretical one-rep max. It’s that you can program a deload week but you can’t help someone reframe their catastrophic thinking. You can adjust their macros but you can’t help them see that eating dessert at a family gathering doesn’t mean they have “no self-control.” You understand progressive overload but you don’t understand why your client is progressively overloading themselves with shame and self-criticism until the whole structure collapses.

This matters more than you think. Behaviour change is cognitive before it’s physical. The decision to train happens in the mind before it happens in the gym. The choice to eat in a particular way is mediated by thoughts, interpretations, and beliefs. You can have the most exquisitely designed program in the world, but if your client interprets one setback as evidence of their fundamental unworthiness, they won’t follow it long enough for it to work.

There’s an evolutionary reason for this, incidentally. Our brains evolved to make rapid, binary assessments in threatening situations. Safe or dangerous. Friend or foe. Fight or flight. This was adaptive when the threat was immediate and physical: a predator, a rival, a natural disaster. But it’s catastrophically maladaptive when applied to modern, complex situations like health behaviour change. One missed workout isn’t a mortal threat, but the brain treats it like one: you’re either succeeding completely or failing completely, you’re either “on track” or you’ve “ruined everything.” There’s no middle ground in threat-detection mode, and your clients are walking around in a constant state of low-level threat response about their own behaviour.

The deeper issue is that we’re meaning-making creatures. We don’t just experience events; we interpret them. We can’t not interpret them. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that we’re “condemned to be free”. We are condemned to interpret our experiences, to make meaning of them, to construct narratives about what they say about us. Your client doesn’t just miss a workout. They miss a workout, and in that moment, they’re constructing a story: “This means I’m unreliable. This means I can’t be trusted. This means I’m the kind of person who fails at things.” The missed workout becomes evidence in a narrative they’re building about who they are. And they’re doing this unconsciously, automatically, destructively.

That’s what you’re actually dealing with. Not laziness. Not lack of motivation. Not even lack of discipline, really. You’re dealing with unconscious meaning-making that’s turning neutral events into identity-defining catastrophes. And unless you have tools to work with that cognitive layer, you’re going to keep losing clients to their own thinking.

How to Use the ABC Model in Coaching: The Framework

The ABC model comes from Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy, developed by Albert Ellis in the 1950s. It’s a clinical tool (i.e. it was designed for therapy), but it’s extraordinarily practical for coaching. You don’t need to be a therapist to use it. You just need to understand how thinking works and how to help someone examine their own thoughts.

Here’s the framework in its simplest form:

A stands for Activating Event. This is the thing that happened. The objective, observable, factual thing. Your client missed a workout. The scales went up two pounds. They ate off their plan at a restaurant. They skipped their morning walk. Whatever it is, the activating event is the stimulus, the trigger, the thing that sets everything in motion.

B stands for Belief. This is the interpretation, the meaning your client assigns to the activating event. It’s what they tell themselves about what happened. “I’m a failure.” “I can’t do this.” “I’ve ruined everything.” “I have no self-control.” “This proves I’m not disciplined enough.” The belief is the story they construct about the event, and it’s almost always immediate and unconscious.

C stands for Consequence. This is the emotional and behavioural result. The feeling and the action that follow from the belief. They feel ashamed, so they avoid you. They feel hopeless, so they quit training for the week. They feel anxious, so they restrict heavily the next day, and trigger a binge-restrict cycle. The consequence seems like the inevitable result of the activating event, but it’s not.

The critical insight here is that: It’s not A that causes C. It’s B.

The event itself doesn’t cause the spiral. The interpretation of the event causes the spiral. The missed workout is neutral data. It becomes catastrophic only through the meaning the client assigns to it. And that meaning, that belief, is where you can intervene.

This is not a new idea. The Stoics understood this two thousand years ago. Epictetus wrote, “Men are disturbed not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.” It’s not the missed workout that disturbs your client; it’s their judgement about the missed workout. Marcus Aurelius: “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.” The ABC model is just a practical framework for working with this ancient wisdom.

There’s a parallel here with existentialist philosophy that’s worth understanding. Viktor Frankl, who survived Auschwitz and went on to found logotherapy, (supposedly) wrote: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” The ABC model makes that space visible and workable. The activating event is the stimulus. The consequence is the response. The belief is what happens in the space between them, and that’s where your client’s freedom lives.

This is fundamentally about radical responsibility. Not responsibility for the event, no, your client didn’t necessarily choose to miss the workout. Life happened. But responsibility for the meaning they assign to it. They’re interpreting the event, and interpretation is inescapable. We’re always interpreting, always meaning-making, always constructing narratives. The question is whether we’re doing it consciously or unconsciously, accurately or distortedly, helpfully or destructively. The ABC model helps you make interpretation conscious so it can be examined and, if necessary, revised.

Understanding how to use the ABC model in coaching means recognising that you’re working with people who are constantly engaged in acts of interpretation. They can’t not interpret. But they can learn to interpret more accurately, more rationally, more helpfully. That’s what you’re teaching them.

Spotting the ABC Pattern With Your Clients

Let me walk you through what this looks like in actual coaching conversations.

Your client messages you: “I’m so sorry, I missed Monday’s workout. I’m useless. I can never stick to anything. I don’t know why I even bother.”

Let’s break this down with the ABC model:

A (Activating Event): They missed Monday’s workout. That’s it. That’s the objective fact. One workout, out of however many they’ve completed with you. Let’s say you’ve been working together for three months and they’ve trained three times a week. That’s roughly 36 sessions completed, and one missed. The event is: one session not attended.

B (Belief): “I’m useless. I can never stick to anything.” Notice the globalisation; one missed session has become evidence of a character defect. Notice the permanence; “never,” as though past behaviour is irrelevant and future behaviour is predetermined. Notice the personalisation; the missed workout isn’t just something that happened; it’s something that reveals a truth about who they are. This is the belief doing damage.

C (Consequence): They don’t train Tuesday. They don’t train Wednesday. They eat poorly because “what’s the point.” They avoid your messages because they’re embarrassed. By the weekend, they’ve written off the entire week. That’s the consequence; it’s not of missing Monday’s workout, but of the belief they formed about missing Monday’s workout.

Here’s another example. Your client weighs themselves after a week of perfect adherence. The scales are up two pounds. They message you: “This isn’t working. My body is broken. I’m going to try that ketogenic diet my friend recommended.”

A: Scales up two pounds after one week. That’s the data. Water retention, glycogen, hormonal fluctuations, waste in the digestive tract, measurement error, or dozens of possible explanations, none of which have anything to do with fat gain over a single week of adherence.

B: “This isn’t working. My body is broken.” They’ve interpreted normal biological variation as evidence that the entire approach is flawed and that there’s something uniquely dysfunctional about their physiology. This belief feels true to them in the moment, even though it’s not supported by any actual evidence.

C: They quit your program and try something extreme and unsustainable. They’ve now ensured the actual outcome they were afraid of (failed progress) by abandoning the approach that would have worked if given more time.

One more example, because this pattern shows up everywhere. Your client goes to a family gathering. There’s cake. They have a slice. Afterwards, they text you: “I have no self-control. I’m sabotaging myself. I can’t be trusted around food.”

A: They ate a slice of cake at a social gathering. That’s the behaviour. One food choice in the context of an otherwise well-managed week.

B: “I have no self-control. I’m sabotaging myself.” They’ve turned a normal human experience (eating something enjoyable at a celebration) into evidence of a character flaw. The belief is that choosing to eat cake reveals their lack of control, as though the only acceptable behaviour is rigidity and restriction.

C: They restrict heavily the next day to “make up for it.” They skip meals, overexercise, create a deficit that leaves them ravenous by evening. Then they binge, confirming the original belief that they “have no self-control.” The belief has created the very behaviour it claimed to describe. This is how binge-restrict cycles start and sustain themselves.

Once you know to look for it, the pattern becomes visible everywhere. Your clients are constantly moving through ABC sequences. Event happens, belief forms, consequence follows. And most of the time, they’re completely unaware they’re doing it. The belief feels like reality, not interpretation. “I’m useless” doesn’t feel like a thought; it feels like the truth.

Most coaches intervene at C. They try to motivate the client back to training. They remind them of their progress. They encourage them to keep going. None of this addresses the actual problem, which is happening at B. The belief is still there, still operating, still generating the same consequences. You can pump someone full of motivation temporarily, but if their thinking hasn’t changed, they’ll spiral again at the next setback.

You’re not a therapist and you don’t need to be. But you can learn to recognise this cognitive pattern. You can learn to distinguish between the event and the interpretation. You can learn to help your clients see what they’re doing with their own thinking. That’s coaching at the level where real change happens.

In each of these examples, the client is engaged in what existentialists call “bad faith.” They’re treating themselves as a fixed essence; “I’m useless,” “I have no self-control,” “My body is broken”; rather than recognising their freedom to act differently. They’ve collapsed their identity into a single event, reifying a moment of behaviour into a permanent character trait. The person who missed Monday’s workout has become “the kind of person who can never stick to anything.” That’s not truth; that’s bad faith. It’s a refusal to acknowledge their own agency, their own capacity to choose differently in the next moment.

The ABC model helps them see they’re doing this. Once they can see it, they can work with it.

What Your Clients Are Really Doing When They Catastrophise

When your client says “I’m a failure” after missing a workout, they’re not just being dramatic. They’re not just “in their feelings.” They’re constructing a coherent narrative about themselves. This is deeper than you might think.

Human beings understand themselves through the stories they tell about their experiences. This is narrative identity theory, which is the idea that we make sense of who we are by constructing narratives that connect our past, present, and anticipated future into a coherent whole. The events of our lives are just raw material; we become authors of our own experience, selecting certain events as significant, interpreting them, weaving them into a story about the kind of person we are.

The belief in the ABC model isn’t just a passing thought. It’s a meaning-making act that shapes your client’s sense of self. When they interpret a missed workout as evidence that they’re “the kind of person who can’t stick to things,” they’re not just describing themselves, they’re actually constructing themselves. The story becomes the self. And once the story is in place, it shapes future behaviour. If you believe you’re the kind of person who can’t stick to things, why would you bother trying? The belief becomes self-fulfilling.

This connects directly to eudaimonia, though your clients would almost certainly never use that term. Aristotle distinguished between simply living and living well: eudaimonia, often translated as flourishing or the good life. Eudaimonia isn’t just feeling happy; it’s about actualising your potential, developing excellence, and living in accordance with virtue. Central to this is phronesis, practical wisdom: the ability to make good judgements in particular situations.

When your clients catastrophise, when they turn one missed workout into “I’m a failure,” they’re practising poor judgement about their own actions. They’re failing at phronesis in a very specific domain: self-evaluation. They’re judging themselves inaccurately, harshly, and distortedly. And inaccurate self-judgement undermines flourishing. You can’t live well if you’re constantly misinterpreting your own experience, constantly drawing false conclusions about your own character.

Learning how to use the ABC model in coaching is actually helping clients develop phronesis. You’re teaching them to judge themselves more accurately, more rationally, more wisely. This isn’t just about feeling better or being more motivated. It’s about developing a virtue: the virtue of accurate self-knowledge and sound judgement. That’s work that contributes to eudaimonia, to genuine human flourishing.

The stakes here are higher than one missed workout. These beliefs accumulate and compound over time. Think about what happens when you repeatedly interpret setbacks as evidence of fundamental character flaws. “I failed at this” becomes “I’m a failure” becomes “I’m the kind of person who fails.” The interpretation hardens into identity. And once it’s identity, it feels unchangeable. “This is just who I am. I’ve always been like this. I’ll never change.”

Your job as a coach is partly to interrupt this consolidation of negative self-identity. To catch it early, before “I struggled with consistency this week” becomes “I’m an inconsistent person.” The former is a description of behaviour that can change. The latter is a claim about essence that feels fixed.

This matters for what psychologists call the three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Self-determination theory suggests that human motivation and well-being depend on satisfying these three needs. Watch what happens to them when catastrophic beliefs take hold:

The belief “I can’t do this” directly undermines competence. Your client stops believing in their own capability. Even when evidence suggests they are capable (they’ve been training consistently, they’ve made progress), the belief overrides the evidence.

The belief “I have no control” undermines autonomy. They stop experiencing themselves as agents of their own behaviour. Things just “happen to them.” They “fall off the wagon” as though it’s something done to them rather than choices they’re making.

The belief “I’ll disappoint everyone” undermines relatedness. They avoid you, avoid accountability, and isolate themselves because they’re ashamed. The very relationships that could support them become sources of anxiety.

So when you’re working with the ABC model, you’re not just helping someone feel better about a missed workout. You’re working to preserve their sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness. You’re protecting the psychological foundations of their motivation and well-being. That’s incredibly important work.

Applying the ABC Model: Your Practical Process

Right, let’s get into how you actually use this with your clients. This is the practical bit, the part you’ll return to again and again until it becomes second nature. Six steps, though you won’t always use all six in one conversation, and that’s fine. You’re building a skill over time, not performing a procedure.

Step 1: Identify the Activating Event (with precision)

Most clients blur A and B together completely. They don’t say, “I missed my workout on Monday.” They say, “I’m terrible, I can’t believe I missed my workout, I’m so useless.” The interpretation is fused with the event in their mind. Your first job is to separate them.

You need to get them to describe what actually happened, factually, without any interpretation layered on top. The activating event should be something you could photograph or record. It should be objective, observable, and verifiable. If you were watching on CCTV, what would you see?

Your coaching questions:

- “What specifically happened?”

- “Walk me through the sequence of events.”

- “What’s the fact here, separate from how you feel about it?”

- “If I were describing this to someone who wasn’t there, what would I say happened?”

Common mistake: accepting their interpretation as the event itself. They say, “I ruined everything by eating that pizza,” and you might nod along. But “ruined everything” isn’t the event, it’s their interpretation. The event is: “I ate pizza on Friday evening.” That’s it. That’s the A.

This precision matters because you’re helping them distinguish between what is and what they make it mean. This is a fundamental epistemic skill: knowing the difference between observation and inference. Most people collapse these categories. They observe something and immediately infer meaning, and they experience the whole thing as one undifferentiated reality. “I ate pizza and ruined everything” feels like a single fact rather than an event plus an interpretation.

When you help them separate these, you’re doing something philosophically important. You’re showing them that reality has a structure: there are events, and there are our interpretations of events, and these are not the same thing. Once they can see this distinction, everything else becomes possible.

Step 2: Excavate the Belief

This is where the real coaching happens. The belief is usually unstated, or only half-stated. Clients jump from event to feeling without articulating the belief in between. They say, “I missed my workout, and I feel terrible,” but they don’t say what they’re telling themselves that’s generating the terrible feeling.

Your job is to make the belief explicit. To bring it out of the shadows and put it in front of both of you where it can be examined.

Your coaching questions:

- “What did that mean to you?”

- “What were you telling yourself when that happened?”

- “What does missing that workout say about you?”

- “When that happened, what conclusion did you draw?”

- “Finish this sentence: ‘This means I’m…'”

Listen carefully to their language. You’re listening for patterns:

Absolutist language: always, never, can’t, impossible, every time, nothing, all. “I never stick to anything.” “I can’t control myself.” “Every time I try, this happens.” This is categorical thinking that admits no exceptions.

Globalisation: one event gets inflated into a universal truth about their identity. “I’m a failure” rather than “I failed at this particular thing.” “I’m undisciplined” rather than “I acted impulsively in this situation.” They’ve taken a specific behaviour and made it a character trait.

Permanence: language that suggests things will never change. “I’ll never get this right.” “I’m always going to struggle with this.” “This is just who I am.” They’ve taken a current state and projected it infinitely into the future.

You’re not trying to fix the belief yet. That comes later. First, you just need to make it visible. You need them to hear themselves say it. There’s real power in this, as simply articulating the belief out loud changes your relationship to it.

Once they say, “I’m telling myself I’m worthless,” something subtle but profound has happened. They’ve moved from being worthless to telling themselves they’re worthless. That’s a different relationship to the thought. There’s a sliver of distance, of perspective. They’re no longer fused with the belief; they’re observing it. That distance is where the work happens.

Connect this to cognitive behavioural therapy’s foundational principle: you can’t challenge what you haven’t articulated. Unconscious beliefs are tyrannical. Conscious beliefs can be examined. Your job at this stage is just to make the belief conscious.

Step 3: Map the Consequence

This part is usually more straightforward because the consequences are often obvious to both of you. They stopped training. They binged. They went quiet for two weeks. They started researching extreme diets. They began weighing themselves multiple times a day. The behavioural and emotional fallout from the belief is usually visible.

But it’s still worth making it explicit: “So when you thought ‘I’m useless,’ what did you do next?”

You want to track both emotional and behavioural consequences:

Emotional consequences: shame, hopelessness, anxiety, anger at themselves, despair, resignation. These are the feelings that arise directly from the belief. Not from the event; from the belief about the event.

Behavioural consequences: avoidance (of training, of you, of scales, of mirrors), compensation (restriction, overexercise, punishment), abandonment (quitting entirely, starting something new), or inaction disguised as action (researching the “perfect” plan instead of following the current one, planning elaborate interventions instead of simply returning to baseline).

That last category is worth paying attention to. Sometimes the consequence looks like action but is actually avoidance. Your client spends three hours researching the optimal macro split instead of just eating the meal they’d already planned. They’re “taking it seriously” and “being proactive,” but what they’re actually doing is avoiding the simple act of continuing with what was working. The belief (“What I’m doing isn’t working”) generates behaviour that feels productive but is actually procrastination or self-sabotage.

When you map the consequence explicitly, you’re completing the chain of causation. You’re showing them: this event happened, you formed this belief about it, and then this feeling and this behaviour followed. The connection between B and C becomes clear. This is often where clients have their first “oh” moment. They see the machinery of their own mind. They see how their interpretation directly generated their response.

Important nuance: don’t just accept surface-level consequences. Sometimes there are layers. They stopped training (obvious consequence), but why? Because they felt hopeless (emotional consequence), but also because they were avoiding you (relational consequence), because they assumed you’d be disappointed (belief about your judgement), which connects back to their original belief about themselves (that they’re a disappointment). Peel the layers when it seems relevant.

Step 4: Reality-Test the Belief (Gently)

Now you can actually work with the belief, but here’s what you don’t do: you don’t dismiss it, you don’t minimise it, you don’t paper over it with reassurance. “Oh, you’re not useless, don’t be silly!” might feel supportive, but it doesn’t help. It doesn’t help because it doesn’t engage with the belief seriously. Your client has formed this belief for reasons, faulty reasons, but reasons nonetheless, and they won’t revise it just because you’ve told them to.

Socratic questioning works best. You’re not telling them they’re wrong; you’re helping them examine their own thinking. You’re being a thinking partner, not a cheerleader.

Your coaching questions:

- “Is that true? Actually true?”

- “What evidence do you have for that belief?”

- “What evidence contradicts it?”

- “Is there another way to interpret this?”

- “If your best friend said this about themselves after missing one workout, what would you say to them?”

- “Is this thought helping you get where you want to go?”

- “Would you apply this same standard to anyone else, or just yourself?”

That last question is particularly powerful. Most clients hold themselves to standards they’d never dream of applying to others. They extend grace to everyone except themselves. Helping them see this double standard can shift something.

You’re reality-testing the belief. Is it empirically accurate? Does the evidence support it? Albert Ellis, who developed REBT, was insistent that irrational beliefs could be disputed on empirical grounds. They’re not just unhelpful; they’re often factually false.

Take the belief “I can never stick to anything.” Is that true? What about the job they’ve held for five years? What about the relationship they’ve maintained? What about the hobby they’ve pursued? What about the 35 out of 36 workouts they’ve completed in the past three months? The belief claims universality (“never”) but the evidence contradicts it. They can stick to things. They have stuck to things. They are, right now, mostly sticking to this thing.

But there is a critical distinction here: you’re not trying to make them feel better. You’re trying to help them think more accurately. Sometimes, accurate thinking is still uncomfortable. If someone has genuinely struggled with consistency in multiple domains of their life, the accurate thought might be: “Yes, I’m finding consistency difficult right now, and that’s something I need to work on.” That’s not comfortable, but it’s more accurate, and more useful, than “I’m a complete failure who can never do anything right.”

The goal is rational thinking, not positive thinking. Rational thinking is thinking that corresponds to reality, that’s based on evidence, that’s proportionate to the situation. Some beliefs will have a grain of truth. They did miss the workout. They are struggling more than they’d like. Acknowledge that. But challenge the globalisation, the permanence, the catastrophising.

“Yes, you missed a workout. That’s true. Does that mean you’re useless? Does one missed session out of 36 mean you ‘never stick to anything’? Or does it mean you stuck to 35 out of 36, which is 97% adherence, which is actually quite good?”

You’re not arguing with them. You’re not debating. You’re genuinely curious about whether the belief holds up under scrutiny. And you’re inviting them to be curious too.

Step 5: Develop Alternative Beliefs

Once you’ve reality-tested the original belief and found it wanting, you need to help them develop an alternative interpretation. Not because the alternative feels better, though it often does, but because it’s more accurate, more rational, more aligned with the evidence.

What would be a more truthful way to interpret this event? Not a toxic-positivity spin where everything’s wonderful, but an honest, realistic, evidence-based interpretation.

The alternative belief needs to meet several criteria:

True: It must be supported by evidence. You’re not asking them to lie to themselves or engage in wishful thinking. If they’ve missed seven workouts in a row, the alternative belief isn’t “I’m amazing at consistency.” It’s “I’m struggling with consistency right now, and I need support to get back on track.”

Specific: It should be about this situation, not their entire identity. “I didn’t follow through on this particular workout” rather than “I’m an unreliable person.” Specificity prevents the globalisation that makes beliefs so damaging.

Helpful: It should lead to different consequences, ideally, consequences that support their goals. “I missed one workout out of 36; I can get back to it tomorrow” leads to different behaviour than “I’m useless and should just quit.”

Moderate: It should avoid swinging to the opposite extreme. If the original belief is “I’m a complete failure,” the alternative isn’t “I’m perfect and never make mistakes.” That’s just a different form of distortion. The alternative is something like “I’m human, I make mistakes, and I’m capable of learning from them.”

Walk through this explicitly with your client:

- “What would be a more accurate way to interpret what happened?”

- “What would you tell someone else in this exact situation?”

- “What’s a thought that’s both honest and helpful?”

- “How might you think about this that keeps you moving forward?”

Example: “I’m a failure” becomes “I missed one workout out of many consistent ones. That doesn’t define me or predict my future. I can choose to train tomorrow.”

Example: “This isn’t working; my body is broken” becomes “Weight fluctuates day to day for many reasons. Two pounds after one week tells me nothing about fat loss. I’ll continue the plan and assess over four weeks.”

Example: “I have no self-control” becomes “I chose to eat something I enjoy at a social occasion. That’s a normal human behaviour, not evidence of a character flaw. I can return to my usual eating pattern tomorrow.”

Notice what these alternatives do: they preserve truth whilst removing catastrophising. They’re not denying reality (yes, they missed the workout; yes, the scales went up; yes, they ate the cake). They’re denying the catastrophic interpretation of reality.

The alternative belief isn’t just “nicer” or “more positive.” It’s more aligned with phronesis: with practical wisdom and good judgement. It’s the belief a wise person would hold. And holding wise beliefs, making sound judgements about your own actions, is part of what it means to flourish.

The alternative belief should also support their development rather than their stasis. “I’m learning consistency” is better than “I must be perfectly consistent” because it frames them as developing, capable of growth, practising something that can be improved. This is Aristotelian too. Virtues aren’t innate; they’re developed through practice. And practice includes imperfect attempts. The person learning consistency will sometimes be inconsistent. That’s not failure; that’s learning.

Step 6: Connect to Action (The Often-Missed Step)

Most coaches stop at step five. They’ve helped the client develop an alternative belief, everyone feels better, and the conversation ends. But the ABC model isn’t complete without connecting the new belief to new behaviour. Otherwise, it’s just a nice cognitive exercise.

Ask explicitly: “If you believed that instead, and if you really believed ‘I missed one workout out of 36 and can train tomorrow no problem’, what would you do differently?”

This completes the circuit. You’re showing them that beliefs drive behaviour. Old belief drove old behaviour. New belief can drive new behaviour. They’re not passive victims of their thoughts; they can change their thoughts and therefore change their actions.

Example:

- Old sequence: “I’m a failure” → feel hopeless → quit for the week

- New sequence: “I missed one session out of many” → feel realistic → train tomorrow as planned

Example:

- Old sequence: “My body is broken” → feel panicked → abandon current plan for something extreme

- New sequence: “Weight fluctuates normally” → feel patient → continue plan, assess over time

Example:

- Old sequence: “I have no self-control” → feel ashamed → restrict, then binge

- New sequence: “I made a normal food choice” → feel neutral → return to usual pattern

This is where the existentialist framework pays off. This is radical responsibility becoming empowering rather than burdensome. Yes, they’re responsible for the meaning they make, but that means they have agency. They’re not determined by events. They’re not at the mercy of circumstances. They’re choosing the interpretation, and they can choose differently. They’re authoring their own experience.

Sartre wrote that we’re “condemned to be free,” and there’s truth to that: you can’t escape interpretation, and can’t escape meaning-making. But within that condemnation is liberation. If you’re always interpreting, always choosing how to understand your experience, then you can interpret in ways that serve you rather than undermine you.

An important practical note here is that you won’t complete all six steps in one conversation, especially early on. Sometimes identifying the ABC is enough work for one session. Sometimes you’ll get through reality-testing, but save the alternative belief for next time. That’s fine. You’re teaching them a thinking tool, not performing emergency surgery. Build the skill gradually, patiently, over weeks and months.

What to Watch Out For

Let me walk you through the common ways coaches misuse the ABC model, because knowing where others trip up will help you avoid the same mistakes.

Pitfall 1: Trying to Skip to D (Disputation) Too Quickly

Coaches are problem-solvers by nature. You want to fix things. So when your client says, “I’m useless for missing that workout,” every instinct in your body wants to immediately reassure them: “No you’re not! Look at all the workouts you’ve done! You’re being too hard on yourself!”

This is disputation: you’re disputing the belief, challenging it, offering counter-evidence. And it’s an important part of the process. But if you rush to it before you’ve properly identified and explored the belief, you’re shadow-boxing. You’re arguing with a belief you haven’t fully understood.

Here’s what happens: the client feels unheard. You’ve jumped straight to reassurance before they’ve had a chance to articulate what they’re actually thinking and feeling. To them, it feels like you’re dismissing their experience. “Of course the coach is saying I’m fine, that’s their job. But they don’t really understand.”

Slow down. Do the exploratory work. Help them articulate the belief fully. Let them hear themselves say it. Explore where it comes from, and what evidence they think supports it. Only then, once the belief is clearly visible to both of you, should you start examining whether it holds up.

The belief needs air before you can effectively challenge it. Rushing past steps one and two to get to step four is like trying to solve an equation before you’ve written it down properly. You’ll miss things.

Pitfall 2: Treating Every Setback as an ABC Problem

The ABC model is powerful, but it’s not universal. Sometimes your client is struggling because their thinking is catastrophic. Sometimes they’re struggling because their circumstances are genuinely difficult, their program is inappropriate, or they’re chronically underfed and exhausted.

Not everything is a cognitive problem. Sometimes the problem is practical. Their schedule genuinely is unworkable. Their home environment genuinely is hostile to change. Their nutrition targets genuinely are too aggressive. Using the ABC model to address a practical problem is like using a screwdriver to hammer a nail; wrong tool for the job.

How do you know which it is? A good rule of thumb is if the emotional or behavioural response is disproportionate to the event, look at B. If the response is proportionate but the circumstances are problematic, look at A.

Client misses one workout and spirals for two weeks? That’s disproportionate. That’s likely an ABC problem. The belief about the missed workout is generating an outsized consequence.

Client consistently can’t fit training into their schedule because they’re working 70-hour weeks with young children and ageing parents to care for? That’s not disproportionate. That’s a genuine practical problem. The ABC model won’t help because their interpretation isn’t the issue, their circumstances are.

Be discerning. Don’t use the ABC model as a way to avoid addressing real practical barriers. Sometimes the most helpful thing you can do is help them restructure their schedule, reduce training frequency, adjust their targets, or acknowledge that now isn’t the right time for aggressive goals.

Pitfall 3: Becoming Their Therapist

Let’s be clear about scope of practice. You’re a coach, not a clinician. The ABC model is a tool for everyday catastrophising, for the normal cognitive distortions that trip people up in behaviour change. It’s not a tool for treating clinical depression, anxiety disorders, trauma, or serious mental health conditions.

If you’re working with someone whose beliefs are connected to trauma, abuse, significant psychiatric symptoms, or suicidal ideation, that’s beyond your remit. The ABC model won’t help, and trying to use it might cause harm. You need to refer out.

When to refer:

- The beliefs are tied to trauma or abuse

- The client mentions thoughts of self-harm or suicide

- The catastrophising is severe and persistent despite your best efforts

- There are signs of clinical depression or anxiety disorders

- Your gut tells you this is above your pay grade

You can still support them whilst they work with a therapist, but you’re not the primary intervention. Know your limits. Build relationships with therapists and counsellors in your area so you have people to refer to when needed. This isn’t failure on your part; it’s professional responsibility.

Pitfall 4: Using REBT Language That Sounds Clinical

Here’s a subtle but important mistake: using the technical language of REBT in a way that creates distance or sounds judgmental.

Don’t say: “Your belief is irrational.” That sounds like you’re calling them irrational, like you’re diagnosing them with a pathology.

Do say: “I’m wondering if that thought is actually accurate,” or “Is that belief helping you or hurting you?”

Don’t say: “Let’s work on disputing your cognitive distortions.” That sounds like you’re running a therapy session.

Do say: “Let’s look at that thought together. Does it hold up when we examine it?”

The framework can be completely invisible to the client. They don’t need to know you’re “using the ABC model.” They just need to experience good coaching. You’re asking thoughtful questions, helping them reflect, guiding them to see their thinking more clearly. That’s coaching.

Over time, if it seems useful, you might teach them the framework explicitly. “You know what you just did? You caught yourself catastrophising. You noticed the thought, questioned it, and came up with a more realistic interpretation. That’s a skill you can use anytime.” But that’s later, once they’ve experienced the process working.

Keep your language conversational, warm, and curious. You’re their thinking partner, not their cognitive behavioural therapist.

Pitfall 5: Dismissing Beliefs That Have Some Validity

Sometimes your client’s belief contains truth, and if you dismiss it wholesale, you’ll lose credibility and damage trust.

They say, “I’m struggling with consistency.” You respond with, “No you’re not! You’ve been so consistent!” But they know they’ve missed several workouts recently. They know they’re struggling more than they were a month ago. Your reassurance rings false.

Better approach: validate the accurate part, challenge the globalising or catastrophising part.

“Yes, you’re struggling with consistency right now, you’re right about that. The past few weeks have been harder. But does struggling right now mean you can’t be consistent? Or does it mean you’re working through a difficult patch and need some support to get back on track?”

Hold the accurate observation whilst preventing it from hardening into a permanent identity. “I’m struggling with consistency” is a description of current behaviour. “I’m an inconsistent person” is a claim about fixed character. The former is workable; the latter feels hopeless.

Don’t paper over genuine struggles. Acknowledge them, work with them, but prevent them from becoming totalising narratives about who your client is.

Pitfall 6: Forgetting That Beliefs Are Often Culturally Shaped

Some beliefs your clients hold aren’t just personal, they’re cultural. They’re absorbing messages from diet culture, beauty standards, productivity culture, social media, their family of origin, their community. These beliefs can be deeply embedded and require more nuance to work with.

“I should be able to control this completely” might be Western individualism speaking. The belief that you’re solely responsible for your outcomes, that needing help is weakness, that struggle indicates personal failure.

“My body is shameful if it’s not perfect” might be internalised beauty standards. Decades of messaging about what bodies should look like, what’s acceptable, what’s worthy of love and respect.

“I should be productive every moment” might be capitalism talking. The belief that rest is laziness, that your worth is tied to your output, that you must always be optimising.

Recognise these larger forces. You’re not going to dismantle diet culture in one coaching session, but you can help clients see when cultural messages are speaking through them rather than as them. “That sounds like something you’ve absorbed from diet culture. What do you actually think?”

This requires cultural sensitivity and humility. Don’t assume your values are universal. Different cultures have different relationships to food, body, discipline, family obligation, and health. Listen carefully, ask questions, and adapt your approach to the person in front of you.

Beyond the Immediate Crisis

Here’s what you need to understand about learning how to use the ABC model in coaching: you’re not just solving today’s problem. You’re teaching a transferable skill that your client will use long after they’ve stopped working with you.

You’re Teaching a Transferable Skill

Over time, and this usually takes months, not weeks, clients learn to catch their own ABC patterns. They start noticing when they’re catastrophising. They recognise the thought as a thought rather than absolute truth. They question it automatically.

You’ll get messages like: “Hey, I caught myself spiralling after missing this morning’s workout. I was telling myself I’m useless, but then I realised that’s not true. I’ve been consistent for weeks, and one miss doesn’t change that. I’ll train tomorrow.”

That’s the goal. They’ve internalised the process. They’re coaching themselves through the model you taught them. They don’t need you to reality-test every belief anymore; they’re doing it on their own.

This is behaviour change at the cognitive level, which is far more sustainable than willpower or external motivation. Willpower feels like a finite resource. Motivation fluctuates. But thinking skills (once developed) become automatic. They shift from effortful practice to unconscious competence. Your client isn’t choosing to reality-test their beliefs anymore; they’re just thinking more accurately by default.

You’ve helped them develop autonomy (they’re self-directing their own thinking), competence (they’re capable of managing their own cognitive spirals), and relatedness (they trust you enough to be vulnerable about their thinking, which deepens your coaching relationship). All three psychological needs are being met, which supports intrinsic motivation and well-being.

The Ripple Effect Beyond Fitness

Clients don’t compartmentalise. They learn to use the ABC model with their fitness struggles, but then they start applying it everywhere else.

Work stress: “My boss’s critical feedback doesn’t mean I’m incompetent. It means this particular piece of work needs revision. I can improve it.”

Relationship conflicts: “One argument doesn’t mean the relationship is failing. It means we disagree about this specific thing and need to talk it through.”

Financial anxiety: “One expensive month doesn’t mean I’ll never be financially secure. It means I overspent this month and need to adjust next month.”

Parenting challenges: “My child’s tantrum in the supermarket doesn’t mean I’m a terrible parent. It means my child is two years old and having a hard time, which is developmentally normal.”

You’ve given them a thinking tool with universal application. Every domain of life involves interpretation, meaning-making, and narrative construction. The ABC model helps in all of them.

This is what makes coaching genuinely transformative rather than transactional. You’re not just changing their body composition or fitness level. You’re changing how they relate to themselves, how they interpret their experience, how they construct meaning from events. That’s deep work with lasting impact.

For Your Coaching Practice Specifically

From a purely practical standpoint, understanding how to use the ABC model in coaching makes you a better coach in ways that directly affect your business.

Better retention: Clients don’t ghost you after one setback because you’ve helped them reframe setbacks as information rather than identity-defining failures. They’re less fragile, more resilient, more able to handle the inevitable bumps in the road. They stay working with you longer, which means better results for them and more stable income for you.

Deeper rapport: You’re helping clients think, not just telling them what to do. You’re meeting them at the level of their actual struggle, which is often cognitive rather than practical. They feel understood in a way most coaches don’t offer. This creates trust, loyalty, and a genuine connection. They’re not just your client; you’re someone who’s helped them understand themselves better.

More sophisticated coaching: You’re working at the level of meaning-making, beliefs, interpretation, and the deep structures that drives behaviour. This is more advanced than “eat this, lift that.” You’re integrating psychology with physiology in a way that makes you genuinely multidimensional as a coach.

Better outcomes: When thinking improves, behaviour improves. It’s not just correlation; the causal pathway runs through cognition. Your clients are more consistent, more able to self-correct, and more psychologically equipped to handle the challenges of behaviour change. Better thinking leads to better results.

Differentiation in a crowded market: Whilst other coaches are selling meal plans and training programs, you’re offering something more valuable: psychological support within your scope of practice. You’re not just a trainer; you’re a coach in the fullest sense—someone who helps people develop not just physical capacity but mental and emotional capacity too.

The Eudaimonic Dimension

By learning how to use the ABC model in coaching, you’re helping clients develop phronesis (practical wisdom) about themselves. This directly contributes to their flourishing.

They’re not just getting healthier bodies. They’re developing better self-judgement, more accurate self-knowledge, and more rational self-evaluation. These are virtues in the Aristotelian sense; excellences of character that support living well.

Health and fitness aren’t just instrumental goods, means to other ends. They’re constituents of eudaimonia when pursued wisely. Physical capability, vitality, and the experience of your body working well are part of what it means to flourish as a human being.

But, and this is crucial, if pursued with self-hatred, catastrophic thinking, rigid perfectionism, they’re not contributing to flourishing even if the body composition improves. You can have visible abs and be miserable. You can be objectively fit by any physiological measure and be psychologically tormented. That’s not eudaimonia. That’s not the good life.

The ABC model helps ensure the process of change supports flourishing, not just the outcome. It ensures that the way your clients relate to themselves whilst pursuing their goals is healthy, rational, and based on sound judgement. That’s what makes the work meaningful.

The Existential Dimension

Ultimately, we’re meaning-making creatures. Viktor Frankl, drawing on his experience in concentration camps, argued that the primary human drive isn’t pleasure or power but meaning. We need our lives to mean something. We need our experiences to cohere into a narrative that makes sense.

When you help clients work with the ABC model, you’re helping them exercise their most fundamental freedom: the freedom to interpret their experience. This is existentially significant work disguised as health and fitness coaching.

You’re helping them see that they’re not determined by events. A missed workout doesn’t determine their identity. A number on the scales doesn’t determine their worth. They’re choosing (perhaps unconsciously, but choosing nonetheless) how to interpret these events, and they can choose differently.

Sartre wrote about “bad faith,” the ways we pretend we’re not free, the ways we treat ourselves as objects rather than subjects. When your client says, “I’m just not a disciplined person, that’s how I am,” they’re in bad faith. They’re treating themselves as a fixed essence rather than acknowledging their freedom to act differently.

The ABC model is a tool for recognising and challenging bad faith. It shows them: you’re not a fixed thing; you’re a person making choices, including choices about how to interpret your own behaviour. And if you’re making choices, you can make different choices.

That’s liberating. It’s also demanding. Radical responsibility is both. But most clients find it empowering once they grasp it. They’re not victims of their own psychology. They’re agents with the capacity to examine and revise their thinking.

What This Tool Can’t Do

Let me be honest about the limits of the ABC model, because I don’t want to oversell it. It’s powerful, but it’s not omnipotent.

It’s Not Sufficient on Its Own

The ABC model doesn’t replace good programming, proper nutrition guidance, or practical behaviour change strategies. It works alongside these tools, not instead of them.

Sometimes the problem genuinely is practical. Their schedule is unworkable. Their environment is actively hostile to their goals. Their program is inappropriate for their current capacity. Their nutrition targets are too aggressive. No amount of cognitive reframing will fix a program that’s fundamentally wrong for someone.

Don’t use the ABC model as a way to avoid addressing real practical barriers. If your client is training six days a week whilst working 70 hours and sleeping five hours a night, the problem isn’t their catastrophic thinking about missed workouts. The problem is that their life is genuinely unsustainable and something needs to give.

Good coaching requires judgement about when the problem is cognitive and when it’s practical. Often it’s both. The ABC model is part of your toolkit, not the whole toolkit.

It Won’t Fix Everything Immediately

Deeply entrenched beliefs don’t shift after one conversation. Some beliefs have been forming for decades. They’re wrapped up in family history, cultural messaging, past trauma, and identity formation. One Socratic dialogue isn’t going to undo all that.

Some beliefs are connected to trauma or clinical mental health issues beyond your scope. You’re not equipped to handle these, and trying to will at best be ineffective and at worst cause harm.

Progress with the ABC model is iterative. You’re planting seeds, not performing surgery. You have one conversation where you help them reality-test a belief. They leave feeling clearer. Then life happens, they spiral again, and you repeat the process. Gradually, over weeks, months, the pattern shifts. The spirals become less frequent, less severe, and shorter. They start catching themselves earlier.

Set realistic expectations. With yourself and with your clients. This is teaching them a skill, and skill acquisition takes time. You’re not failing if they don’t immediately master cognitive reframing. You’re succeeding if they’re gradually, incrementally improving.

It Requires Willingness From the Client

Some clients aren’t ready to examine their thinking. They want you to fix them. They want the magic meal plan or training program that will finally work. They’re not interested in looking at their beliefs, their interpretations, their meaning-making.

That’s fine. Meet them where they are. You can’t force insight. You can plant seeds (e.g. ask occasional questions that invite reflection) and then let it rest. They might become ready later. Or they might not, and that’s their choice.

The ABC model only works with clients who are willing to engage with it, who are curious about their own thinking, who are open to examining their beliefs. For clients who aren’t ready, focus on the practical elements of coaching and wait for the right moment to introduce the cognitive work.

Cultural and Contextual Limitations

The ABC model comes from Western clinical psychology. It was developed in 1950s America by Albert Ellis. It carries assumptions from that context: emphasis on individual agency, rational thinking as the highest good, and changing internal states rather than external circumstances.

Some clients from different cultural backgrounds might find this framing strange or insufficient. In more collectivist cultures, the emphasis on individual interpretation might feel alienating. The assumption that you should question beliefs might conflict with values around tradition, authority, or community wisdom.

Be sensitive to this. Adapt your language and approach to the person in front of you. Don’t assume the ABC model is universally appropriate or that your way of using it is the only way.

Similarly, context matters. A client living in poverty with multiple systemic barriers to health isn’t suffering primarily from catastrophic thinking. They’re dealing with genuine, structural disadvantage. The ABC model can still be useful (helping them avoid compounding external stress with self-blame), but don’t let it become a way of individualising systemic problems.

The Tool Is Neutral, Your Use of It Matters

Finally, the ABC model can be used mechanically or with real presence and empathy. You can apply it like a technician following a protocol, or you can use it as a framework for genuine human connection and understanding.

Don’t hide behind the framework to avoid genuine engagement. The Socratic questioning only works if there’s real curiosity and care behind it. If you’re just running through the steps without actually listening, without actually trying to understand your client’s experience, they’ll sense it. The technique won’t land.

Your clients need to feel that you’re with them, not diagnosing them. That you’re genuinely interested in their thinking, not just trying to fix them. The ABC model is most powerful when it’s invisible; when the client just experiences you as someone who asks good questions, who helps them think more clearly, who genuinely cares about their wellbeing.

The framework is a tool. Tools are only as good as the person wielding them.

Making This Second Nature

Now, let’s walk through how you actually integrate this into your coaching practice, how you move from “this is a technique I’m trying” to “this is just how I coach.”

Start With Yourself

Before you use the ABC model with clients, notice it in your own life. This is non-negotiable. You can’t teach what you don’t practice. You can’t help others examine their thinking if you’re not examining your own.

Pay attention to your own ABC patterns:

When a client cancels, what do you tell yourself? Is it “They’re not committed” (belief) which leads to resentment and disengagement (consequence)? Or is it “Something came up” (belief) which leads to curiosity about what happened and an offer to reschedule (consequence)?

When your content doesn’t get the engagement you hoped for, what’s your interpretation? Is it “I’m terrible at this, no one cares what I have to say” (belief) which leads to avoiding content creation for weeks (consequence)? Or is it “This particular piece didn’t land, I wonder why, and what might I try differently next time” (belief) which leads to experimentation and improvement (consequence)?

When you have a bad training session, when your lifts feel heavy, when you’re not hitting your targets, what belief arises? “I’m getting weaker, I’m losing everything, I’m failing”? Or “I’m tired today, probably need more recovery, I’ll adjust and see how next session goes”?

Notice your own catastrophising. Notice your own globalisation and permanence bias. Notice when you’re treating one event as evidence of your entire character. Once you can see it in yourself, you’ll recognise it more easily in your clients.

If you’re asking clients to examine their meaning-making but avoiding your own, there’s a dishonesty there. Not a deliberate lie, but an inauthenticity nonetheless. Clients sense it even if they can’t articulate it. They know, on some level, whether you’re practising what you’re preaching.

Model the self-awareness you want your clients to develop. When appropriate, share your own process: “I noticed myself catastrophising about that client cancellation. Caught myself thinking ‘This person doesn’t value what I offer,’ which isn’t actually true, they just had a scheduling conflict. Once I reality-tested that thought, I felt fine about it.”

You’re showing them what it looks like to live with this kind of self-awareness. That’s more powerful than any technique you teach them.

Practice Incrementally With Clients

Don’t try to do the full six-step process in your first attempt. Build the skill gradually, starting with the simplest piece.

Phase one: Just identify the A (activating event)

Start here. For several weeks, just practice helping clients separate events from interpretations. When they say, “I’m terrible, I missed my workout,” respond with: “What actually happened? Walk me through it.”

Get good at hearing the difference between “I missed the workout” (event) and “I’m terrible” (interpretation). Stop accepting their interpretations as facts. This alone will change your coaching conversations.

Phase two: Add the B (belief identification)

Once you’re comfortable with phase one, start excavating beliefs. “What did that mean to you? What were you telling yourself?”

Listen for the patterns I described earlier: absolutism, globalisation, permanence. Get comfortable asking follow-up questions: “When you say ‘I never stick to anything,’ what makes you think that? What’s the evidence?”

You’re not disputing yet. You’re just making beliefs visible, helping clients articulate what they’re telling themselves.

Phase three: Add disputation and reframing

Now you can start reality-testing beliefs and helping clients develop alternatives. “Is that actually true? What evidence contradicts it? What’s another way to look at this?”

This takes practice. It can feel awkward initially. You might worry you’re being confrontational or dismissive. That’s normal. Keep going. Pay attention to how clients respond. Adjust your tone and approach based on their reactions.

Phase four: Make it invisible

Eventually, you stop thinking about the steps. You just ask good questions naturally. You hear a catastrophic belief, and without conscious thought, you’re helping the client examine it. The framework has become internalised, automatic.

This is the goal. The ABC model becomes just how you think about cognition and behaviour. It’s not a technique you apply; it’s a lens through which you understand what’s happening with your clients.

Make the Framework Invisible (Until It’s Useful to Name It)

You don’t need to use ABC terminology with clients, especially initially. The structure can be completely invisible. You’re just asking questions, helping them reflect, guiding them to examine their thinking.

Later, once they’ve experienced the process working, you might teach them the framework explicitly: “You know what you just did? You noticed you were catastrophising about the scales. You caught the thought, ‘This isn’t working’, and you questioned it. You looked at the evidence and came up with a more realistic interpretation. That’s using the ABC model. You can do this anytime you notice yourself spiralling.”

Once they know the framework, they have language for what’s happening in their mind. They can catch themselves: “I’m doing that ABC thing, missed workout is the A, ‘I’m useless’ is the B, I need to question that before it leads to C.”

But wait until they’re ready. Some clients will never care about the framework; they just want to feel better and behave differently. That’s fine. The model can stay invisible forever if that works best for them.

Keep Learning

The ABC model is one tool from REBT, which is one approach within a broader CBT system, which is one part of a much larger behaviour change science. Don’t stop here.

Other approaches worth exploring:

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Especially useful for values clarification, psychological flexibility, and defusion from thoughts. Where REBT focuses on changing irrational beliefs, ACT focuses on changing your relationship to thoughts; seeing them as mental events rather than truths you must obey.

Motivational Interviewing (MI): Essential for working with ambivalence and resistance. Most behaviour change involves ambivalence: your client wants to change and doesn’t want to change simultaneously. MI gives you tools for navigating this.

Implementation intentions: Bridging the gap between intention and action. “If-then” planning that makes behaviour more automatic and complements the ABC model beautifully. You help them develop more rational beliefs, then you help them translate those beliefs into specific actions.

Habit formation research: Understanding how behaviour becomes automatic, how to design environments that support good habits, and how to stack new behaviours onto existing routines.

The more psychology you understand, the better coach you become. Each framework gives you another way of seeing what’s happening with your clients, another tool for helping them.

Whilst other coaches are in endless debates about optimal protein timing, whether you should train to failure, or the superiority of their preferred dietary approach, you’re learning how people actually change. That matters more than any programming variable or nutritional detail (although you do still need knowledge here).

Physiology knowledge is table stakes. It’s necessary but not sufficient. What separates good coaches from excellent coaches is psychology. Understanding how people think, what drives their behaviour, how to work with resistance and ambivalence and self-sabotage. That’s the frontier.

Build a Referral Network

Know which therapists, psychologists, and counsellors in your area you can refer to when needed. Have these relationships established before you need them.

When you recognise that a client’s issues are beyond your scope—trauma, clinical depression, anxiety disorders, anything that requires professional mental health treatment—you need somewhere to send them. If you’re scrambling to find a therapist in the moment, you’re not being as helpful as you could be.

Build relationships with mental health professionals. Let them know what you do, how you work with clients, and what kinds of issues you’re equipped to handle. Ask them about their approach, who they work with, and whether they take new clients. Create a list of professionals you trust.

This makes it easier to recognise when someone needs more than you can provide. You’re not abandoning them; you’re connecting them with the right support. That’s professional responsibility, and clients appreciate it.

The Real Work of Coaching

Return to that scenario from the beginning. Your client who texted after missing Monday’s workout. Who spiralled. Who went silent. Who ghosted you for a week and then came back apologetic and defeated, talking about “starting fresh.”

With the ABC model, you now see what’s actually happening. You’re not just seeing someone who missed a workout. You’re seeing someone who missed a workout (A), interpreted it as evidence that they’re fundamentally incapable and useless (B), and responded by avoiding training, avoiding you, and mentally writing off all their previous progress (C).

You’re not solving the missed workout problem. That’s trivial. The practical solution is: train tomorrow. But that’s not the real problem. The real problem is the meaning-making process. The way they’ve taken one neutral event and constructed it into a catastrophe. The way they’ve collapsed their entire identity into one moment of imperfect behaviour.

That’s what you’re working with. That’s the real coaching.

This isn’t about being a therapist. You’re not treating mental illness. You’re not doing deep psychodynamic work on their childhood. You’re staying firmly within your scope as a coach. But within that scope, you’re helping them develop more rational, more accurate, and more helpful ways of thinking about their behaviour. That’s legitimate coaching work. That’s the work that actually helps people change.

The physiology knowledge matters enormously. You need to understand training adaptation, progressive overload, periodisation, nutrition, energy balance, and recovery. You need to be able to program effectively. None of that is optional. That is why we have entire courses on them.

But it’s insufficient on its own. Learning how to use the ABC model in coaching isn’t replacing your training knowledge, it’s complementing it. You’re becoming a coach who can work with both the body and the mind. Who understands that behaviour happens at the intersection of physiology and psychology. Who recognises that your clients don’t fail because their program is wrong; they fail because their thinking derails them before the program has time to work.

You’re helping people develop not just healthier bodies but healthier relationships with themselves. That’s work that contributes to their flourishing. That’s work that helps them exercise their freedom to interpret their experience in ways that serve them rather than destroy them.

That’s what separates good coaching from mere instruction. Anyone can hand someone a program and tell them what to eat. That’s not coaching; that’s dispensing information. Coaching is helping someone navigate the psychological challenges of actually implementing the program. Coaching is working with the thinking that gets in the way. Coaching is recognising when someone is trapped in a catastrophic interpretation and helping them see another way.

The ABC model gives you a framework for this work. It gives you questions to ask, a process to follow, a way of understanding what’s happening in your client’s mind. It makes you more effective at the part of coaching that actually matters: the part where you help someone change their behaviour in a lasting way.

What would change in your coaching practice if you could help clients reframe their thinking as skilfully as you can program their training? What kind of coach would you become if you took their psychology as seriously as their physiology? What would be possible for your clients if you could help them see that one missed workout doesn’t define them, that the scales fluctuating is normal, that eating something enjoyable isn’t evidence of moral failure?

That’s the work. That’s what learning how to use the ABC model in coaching makes possible. Not just better compliance. Not just improved retention. But genuine transformation in how your clients understand themselves and their capacity for change.

Having said all of that, you do still need a working model of physiology, nutrition and training to actually get results. So, for those of you ready to take the next step in professional development, we also offer advanced courses. Our Nutrition Coach Certification is designed to help you guide clients through sustainable, evidence-based nutrition change with confidence, while our Exercise Program Design Course focuses on building effective, individualised training plans that actually work in the real world. Beyond that, we’ve created specialised courses so you can grow in the exact areas that matter most for your journey as a coach.

If you want to keep sharpening your coaching craft, we’ve built a free Content Hub filled with resources just for coaches. Inside, you’ll find the Coaches Corner, which has a collection of tools, frameworks, and real-world insights you can start using right away. We also share regular tips and strategies on Instagram and YouTube, so you’ve always got fresh ideas and practical examples at your fingertips. And if you want everything delivered straight to you, the easiest way is to subscribe to our newsletter so you never miss new material.

References and Further Reading

David D, Cotet C, Matu S, Mogoase C, Stefan S. 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(3):304-318. doi:10.1002/jclp.22514 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28898411/

King AM, Plateau CR, Turner MJ, Young P, Barker JB. A systematic review of the nature and efficacy of Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy interventions. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0306835. Published 2024 Jul 9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0306835 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11232995/

Turner MJ. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), Irrational and Rational Beliefs, and the Mental Health of Athletes. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1423. Published 2016 Sep 20. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01423 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5028385/

Ziegler DJ, Leslie YM. A test of the ABC model underlying rational emotive behavior therapy. Psychol Rep. 2003;92(1):235-240. doi:10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.235 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12674289/

Shomali Ahmadabadi MS, Rezapour Mirsaleh Y, Yousefi Z. Effectiveness of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) on Self-Control and Impulsivity in Male Prisoners. Iran J Psychiatry. 2024;19(2):185-195. doi:10.18502/ijps.v19i2.15104 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11055976/

Rnic K, Dozois DJ, Martin RA. Cognitive Distortions, Humor Styles, and Depression. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12(3):348-362. Published 2016 Aug 19. doi:10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1118 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4991044/

Persons JB, Marker CD, Bailey EN. Changes in affective and cognitive distortion symptoms of depression are reciprocally related during cognitive behavior therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2023;166:104338. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2023.104338 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37270956/

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11392867/

Wang CKJ, Liu WC, Kee YH, Chian LK. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon. 2019;5(7):e01983. Published 2019 Jul 19. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01983 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31372524/

Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2013;7(6):395-404. doi:10.1177/1559827613488867 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27547170/

Rethorn ZD, Bezner JR, Pettitt CD. From expert to coach: health coaching to support behavior change within physical therapist practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;38(13):2352-2367. doi:10.1080/09593985.2021.1987601 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34620046/