Would you feel confident in your understanding of the basics of behaviour change and habit formation? I ask this because something that took me way too long to figure out is that the difference between a mediocre coach and a world-class one has almost nothing to do with how much you know about exercise science or nutrition. I spent my first few years as a coach absolutely stuffed with knowledge about macronutrients, periodisation, and biomechanics, and I watched client after client nod enthusiastically during our sessions, agree with everything I said, and then… not do it. They’d come back week after week with the same sheepish look, the same apologies, the same promises that this week would be different. And I’d get frustrated because I knew exactly what they needed to do. The plan was perfect. Why weren’t they following it?

What I eventually learned is that our clients don’t have an information problem. They have a behaviour change problem. And until you understand the basics of behaviour change and habit formation, you’re going to keep running into that same wall, watching people fail to implement advice that you know would transform their lives if they’d just do it.

The breakthrough for me came when I stopped thinking of myself as a teacher and started thinking of myself as a guide through a very specific process. Because behaviour change isn’t random. It’s not about having enough willpower or wanting it badly enough. It follows patterns, and once you understand those patterns, everything about your coaching becomes more effective. You stop blaming clients for not following through and start adjusting your approach to meet them where they actually are.

TL;DR

Most coaches don’t fail because they lack knowledge about exercise or nutrition, but because they don’t understand how behaviour change actually works. Your clients already know they should eat better and move more. Their problem isn’t information, it’s implementation.

Real change doesn’t come from willpower or motivation, which are unreliable and deplete quickly. Instead, it follows predictable patterns rooted in neuroscience and psychology. The habit loop (cue, routine, reward) governs every behaviour, and successful coaching means engineering environments and starting absurdly small so change feels natural rather than forced. You must meet people where they are in their readiness to change, not where you want them to be. Focus on identity over outcomes, helping clients become the kind of person who does these things rather than someone trying to achieve a goal. Celebrate tiny wins, practice self-compassion when setbacks happen, and remember that consistency beats intensity every time.

Ultimately, the coaches who excel don’t just prescribe programs; they understand that small, sustainable steps compound into genuine transformation, building not just better bodies but the practical wisdom and self-trust that lasts a lifetime.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 The Fundamental Misunderstanding: Coaching Isn’t Teaching

- 3 The Habit Loop: Your Foundation Framework

- 4 Meeting People Where They Are: The Stages of Change

- 5 The Power of Starting Ridiculously Small

- 6 Compound Interest for Behaviour: How Tiny Habits Create Transformation

- 7 Environment Design: The Hidden Lever of Behaviour Change

- 8 Join 1,000+ Coaches

- 9 Identity-Based Change: Becoming vs. Achieving

- 10 Common Coaching Mistakes That Undermine Behaviour Change

- 11 Cognitive Behavioural Tools for Coaches

- 12 Self-Compassion: The Essential Ingredient for Sustainable Change

- 13 Your Practical Coaching Framework: Putting It All Together

- 14 Practice These Principles in Your Own Life First

- 15 What Makes World-Class Coaching: Understanding The Basics of Behaviour Change and Habit Formation

- 16 Author

The Fundamental Misunderstanding: Coaching Isn’t Teaching

Most of us start our coaching careers with a fundamental misunderstanding. We treat coaching like teaching. We think our job is to transfer information from our brain to the client’s brain, and once they know what to do, they’ll do it. This makes sense, right? It’s how most education works. But the problem is that knowing and doing are completely different things. Every single one of your clients who’s struggling already knows they should eat more vegetables and move more. They don’t need you to tell them that. They need you to help them actually do it, which requires understanding the basics of behaviour change and habit formation at a much deeper level than most coaches ever reach.

The other trap we fall into is believing that motivation and willpower are the primary tools for change. We pump our clients up, we give inspiring speeches, and we post motivational quotes on Instagram. And sure, motivation feels good. It creates a temporary spike in action. But motivation is like the weather; it comes and goes. You can’t build a sustainable practice on something that fluctuates that much. Willpower is even worse because it feels like a finite resource that gets depleted throughout the day. Willpower relies on the prefrontal cortex, which feels like it fatigues with use. It’s why you can resist the donuts in the morning but give in by evening. You get the feeling of running out of cognitive resources.

If your coaching strategy requires clients to white-knuckle their way through every decision, you’re setting them up to fail. And something most coaches don’t realise with this stuff is that you’re also fighting millions of years of evolution. Our brains didn’t evolve for long-term health optimisation. They evolved for immediate survival. The person who ate the high-calorie food when it was available survived uncertain times. The person who conserved energy instead of exercising unnecessarily had reserves for escaping predators. When your client chooses the cookie over the apple, they’re not weak. They’re responding to deeply wired preferences for immediate caloric reward. This is what is often called hyperbolic discounting, which is the tendency to heavily discount future rewards in favour of immediate ones.

Now, understanding all of this removes moral judgment from coaching and makes you dramatically more effective. Your client isn’t failing at behaviour change because of character defects. They’re navigating a mismatch between the environment they evolved for and the one they’re living in. We evolved to move constantly and rest occasionally; now we rest constantly and move occasionally. We evolved with natural circadian rhythms dictated by sunrise and sunset; now we have artificial light and screens disrupting our sleep-wake cycles. The behaviours we’re coaching people toward aren’t arbitrary preferences. They’re helping clients realign with what their bodies were actually designed for. Sleep, stress management, good nutrition and exercise aren’t luxuries; they’re biological necessities.

And when we ignore them, the body protests. Chronic stress floods the system with cortisol, which impairs decision-making, reduces impulse control, and increases cravings for high-calorie foods. Sleep deprivation has similar effects. Just one night of poor sleep measurably reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is the part of your brain responsible for good judgment. This reframes what we used to call “lack of willpower” as a physiological state that needs addressing. A client who’s chronically stressed and sleep-deprived doesn’t need a lecture about discipline. They need help reducing stress and improving sleep, which will naturally improve their capacity for behaviour change.

Ultimately, what I want you to understand is that behaviour change is a skill that follows predictable patterns. When someone can’t stick to a habit, it’s not a character flaw. It’s usually just a mismatch between their current capacity for change and what you’re asking them to do. Once you see it this way, everything shifts. You stop trying to force change and start designing conditions where change becomes natural.

The Habit Loop: Your Foundation Framework

So let’s talk about what actually drives behaviour. Every single habit, whether it’s drinking water first thing in the morning or stress-eating cookies at night, follows the same basic three-part loop: cue, routine, reward. The cue is the trigger that initiates the behaviour. The routine is the behaviour itself. The reward is what your brain gets from doing it, which reinforces the whole loop and makes you more likely to do it again next time you encounter that cue.

This is fundamental neuroscience. The habit loop gets encoded in the basal ganglia, a primitive part of your brain involved in pattern recognition and procedural learning. Once a behaviour becomes habitual, it runs automatically, freeing up your prefrontal cortex for other decisions. This is why habits are so powerful, and why trying to change them through conscious effort alone is so exhausting. You’re trying to override an automatic process with a manual one, which requires constant cognitive resources.

Understanding this loop changes how you coach because it gives you a framework instead of just a collection of random strategies. When a client tells you they can’t stick to their post-workout protein shake, you’re not just throwing solutions at the problem. You’re investigating the loop. Is there a clear cue? Maybe they finish their workout, but then the cue gets lost in the chaos of getting home, showering, and jumping into their day. Is the routine too complicated? Maybe making the shake requires too many steps when they’re tired. Is there a satisfying reward? Maybe the shake tastes terrible or doesn’t give them any immediate positive feeling.

The beautiful thing about this framework is that you can troubleshoot any habit by examining these three components. You can deliberately design cues that are impossible to miss. You can simplify routines until they’re almost effortless. You can identify or create rewards that actually feel rewarding to that specific person. This is what behavioural designers and choice architects do: they engineer the environment to make desired behaviours more likely. And this is exactly what you’re doing as a coach. You’re not just prescribing exercises and meal plans. You’re engineering behaviour change systems.

Meeting People Where They Are: The Stages of Change

But something crucial that too many coaches miss, and something that is absolutely fundamental to the basics of behaviour change and habit formation: not everyone is ready for the same level of change at the same time. There are predictable stages people move through when changing behaviour, and trying to force someone into action when they’re not ready is like trying to harvest a crop before it’s grown. You’re just going to damage the whole thing.

The Transtheoretical Model describes these stages clearly. In the earliest stage, pre-contemplation, people aren’t even thinking about changing. They might be vaguely aware that something isn’t ideal, but they’re not considering action. Then they move into contemplation, where they’re thinking about change but haven’t committed to anything. They’re weighing pros and cons, feeling ambivalent. Then comes preparation, where they’re getting ready to take action, maybe gathering information or making plans. Then action, where they’re actively doing the new behaviour. And finally, maintenance, where they’re working to sustain the change over time.

The mistake I see newer coaches make constantly is treating every client like they’re in the action stage. You meet someone who’s thinking about maybe starting to exercise someday, and you immediately give them a four-day-a-week training program. You meet someone who’s contemplating their nutrition, and you hand them a detailed meal plan with macro targets and meal timing. This doesn’t work because the strategies that help someone in the contemplation stage are completely different from the strategies that help someone in the action stage.

This is where techniques from motivational interviewing become invaluable. When someone is contemplating change, they need help exploring their ambivalence. They need to talk through what might be good about changing and what might be hard about it. They need to connect with their own reasons for wanting to change, not yours. In motivational interviewing, we use open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summarising. This is what’s called the OARS approach. You’re not telling them what to do. You’re helping them hear themselves and find their own motivation.

Giving them an action plan when they’re in the contemplation stage usually just creates resistance because they’re not ready for it yet. But when someone is in the preparation or action stage, then yes, they need concrete strategies and clear plans. They need what Gabriele Oettingen calls mental contrasting: visualising both the positive outcome and anticipating the obstacles. Her WOOP method (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) actually increases success more than positive visualisation alone because it prepares people for the inevitable difficulties rather than setting them up for disappointment when things get hard.

Learning to identify which stage a client is in and adjust your coaching accordingly is one of the most powerful skills you can develop. It means you stop wasting energy pushing people who aren’t ready and start meeting them exactly where they are, which paradoxically helps them move forward faster. This is respecting what Sartre called our radical freedom. We’re “condemned to be free,” meaning we can’t escape the responsibility of choice. Your job isn’t to take away that freedom by imposing your plan. It’s to help clients reclaim their agency and own their choices, which creates lasting change.

The Power of Starting Ridiculously Small

Now, when someone is ready for action, there’s another principle that separates effective coaches from ineffective ones, and it’s central to the basics of behaviour change and habit formation: the understanding that small changes create big results, but big changes usually create no results at all. I know this sounds backwards. We’ve been conditioned to think that transformation requires dramatic overhauls. Wake up at five in the morning, meal prep for the entire week, hit the gym six days a week, and cut out sugar completely. And sure, if someone could actually do all of that and sustain it, they’d see results. But almost no one can, especially straight away, and the attempt usually leads to burnout and giving up entirely.

The brain doesn’t respond well to massive change. It perceives it as a threat. Everything in your nervous system is designed to maintain homeostasis, to keep things the same, because from an evolutionary perspective, the same equals safe. Dramatic change activates your threat detection system. Your amygdala sounds the alarm. Your body mobilises stress responses. When you try to change too much too fast, you activate powerful resistance mechanisms that are designed to pull you back to baseline.

But small changes slip under the radar. They don’t trigger that threat response. And once a small behaviour becomes automatic, it creates a foundation for the next small change. There’s a principle in neuroscience: neurons that fire together wire together. This is Hebbian learning. Each time you repeat a behaviour, you strengthen the neural pathway that supports it, making it more automatic. The key is consistency, not intensity, because you’re literally rewiring your brain through repetition.

Compound Interest for Behaviour: How Tiny Habits Create Transformation

I’m talking about truly small changes here, what I call the minimum viable habit. Not “small” like going to the gym three times a week instead of five. Small like doing two pushups every morning. Like adding one vegetable to whatever you’re already eating. Like walking for five minutes after lunch. These feel almost laughably small, and that’s exactly the point. They’re so small that there’s no way to fail at them, no way for your threat detection system to sound the alarm, and that consistency is what rewires the brain.

What happens over time is that these tiny habits compound. It’s like the compound interest of behaviour where small, consistent deposits create exponential growth over time. Two pushups becomes five becomes ten, and eventually becomes a full workout routine. One vegetable becomes a habit of including vegetables becomes actually craving vegetables. Five-minute walks become a daily movement practice that you genuinely miss when you skip it. And beyond the practical accumulation of these behaviours, something psychological happens too. Each time you do what you said you’d do, even if it’s tiny, you’re proving to yourself that you’re the kind of person who follows through. You’re building what is called self-efficacy, which is confidence in your ability to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific outcomes.

Self-efficacy comes from four sources: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological states. As a coach, you can deliberately cultivate all four. Small wins create mastery experiences. Sharing stories of others who succeeded creates vicarious experiences. Your encouragement provides verbal persuasion. And helping clients manage stress and sleep improves their physiological state, which affects their perception of their own capabilities. Every tiny habit success is a deposit in the self-efficacy account, and that account pays dividends in bigger changes later.

Something else that’s happening with these tiny habits is that you’re taking “reps for your identity.” Every small action is practice at being the kind of person you’re becoming. This connects to an idea from Aristotle that I think is profoundly relevant to coaching. Aristotle didn’t see virtue as something you have, but something you do; excellences developed through practice, which he called habituation. You don’t become courageous by thinking about courage. You become courageous by practising courageous acts until they become characteristic of you.

You become disciplined by practising discipline. You become healthy by practising healthy behaviours. The goal isn’t just outcomes like weight loss or muscle gain. The goal is developing excellence of character and becoming the kind of person who lives well. This is what Aristotle called eudaimonia, often translated as happiness but more accurately understood as human flourishing. It’s not about feeling good in the moment. It’s about living according to virtue, which creates a deep sense of living well.

Environment Design: The Hidden Lever of Behaviour Change

But even small habits won’t stick if you’re relying purely on willpower to make them happen, which brings me to one of the most important principles in the basics of behaviour change and habit formation, and something that changed my entire coaching approach: the environment is stronger than willpower. You can have the best intentions in the world, but if your environment is set up to make the unhealthy choice easy and the healthy choice hard, you’re going to lose that battle most of the time.

Think about it this way: if there’s a bowl of sweets on your desk, you’re going to eat more sweets than if the sweets are in a cupboard across the room. Not because you’re weak, but because the environment makes it effortless. Every time you look up, there’s the cue. The routine requires zero effort. The reward is immediate. You’d have to actively use willpower to not eat the sweets, burning through your limited prefrontal cortex resources all day long. But if the sweets are across the room, you have to actively use willpower to get up and get it. The behaviour you want is no longer the path of least resistance.

This is what Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein call “nudge theory” or choice architecture. The idea is simple but profound: small changes in how choices are presented dramatically affect which choices people make, even when they have complete freedom to choose. Thaler calls it “libertarian paternalism”; preserving freedom while designing the environment to make better choices easier. And this is exactly what you’re doing as a coach. You’re not forcing anyone to do anything. You’re helping them engineer their environment so the desired behaviour becomes the default.

This is where coaching gets really practical, where understanding the basics of behaviour change and habit formation translates into concrete intervention. Instead of asking clients to develop superhuman willpower, you help them design environments where the desired behaviour is the default. You want to drink more water? Put a full water bottle on your desk every morning before you do anything else. You want to work out in the morning? Lay out your workout clothes and put your shoes right next to the bed. You want to eat less junk food? Don’t buy it. Keep it out of the house entirely.

I know that sounds simplistic, but we dramatically underestimate how much our behaviour is shaped by what’s immediately available to us. This is what behavioural economists call default bias, where we tend to stick with whatever the default option is because changing requires effort. And status quo bias, where we have a strong preference for keeping things the way they are. If the default in your house is that there’s ice cream in the freezer, you have to actively override the default every single time you’re tired or stressed. That’s exhausting. But if the default is that there’s no ice cream in the house, you’d have to actively override that default by getting dressed, getting in the car, driving to the shop, and buying it. The friction makes the difference.

The flip side is also true. You can add friction to behaviours you want to do less of. This is what I call friction engineering, where you are deliberately adding or removing friction to shape behaviour. Want to spend less time on social media? Delete the apps from your phone and only access them on your computer. Every time you want to scroll, you have to make a conscious decision to go to your computer, open the browser, and type in the URL. That extra friction is often enough to break the automatic reaching-for-phone pattern. Want to stop snacking late at night? Make a rule that you have to brush your teeth right after dinner, which makes eating again less appealing and creates a clear cue that the eating window is closed.

These environmental tweaks don’t require willpower because they change the landscape in which decisions get made. You’re not fighting against your brain’s natural tendencies. You’re working with them. You’re designing systems that make success easier than failure, which is infinitely more sustainable than relying on constant self-control.

Identity-Based Change: Becoming vs. Achieving

What’s interesting is how this connects to something even deeper about behaviour change, something that touches on fundamental questions about human nature and the good life. Most clients come to you with outcome goals. They want to lose twenty pounds. They want to run a marathon. They want to fit into their old jeans. And there’s nothing wrong with having these goals, but if that’s the only level you’re working at, the changes rarely last.

Outcome-based change says, “I want to achieve this thing, so I’ll do these behaviours until I get there.” Identity-based change says, “I’m becoming this type of person, and this is what this type of person does.” The first approach makes the behaviour a means to an end, something you have to force yourself to do. The second approach makes the behaviour an expression of who you are, which means it’s self-reinforcing rather than requiring constant willpower.

This distinction touches on something the existentialists understood deeply. Sartre said that “existence precedes essence”, which effectively means that we’re not born with a fixed nature. We create ourselves through our choices. Every workout, every healthy meal, every moment of showing up for yourself is an act of self-creation. You’re not discovering who you are. You’re deciding who you are. Nietzsche had a similar idea with his concept of “becoming who you are”: the paradox that you have to create yourself in order to become yourself.

When someone says, “I’m trying to work out more because I want to lose weight,” they’re in outcome mode. The behaviour is a chore in service of a goal. But when someone says, “I’m becoming someone who moves their body every day,” they’re in identity mode. Now working out isn’t about the weight loss, it’s about being consistent with who they’re becoming. And here’s the thing, even if they don’t feel like working out on a particular day, they’re more likely to do it anyway because not doing it would create an identity conflict. We’re wired to act in ways that are consistent with how we see ourselves.

Viktor Frankl, who survived the Nazi concentration camps, developed what he called logotherapy, which is based around the idea that meaning comes from how we respond to life’s demands. A client who shows up for their health consistently, even when it’s hard, is practising responsibility and self-respect. They’re not just getting fitter; they’re living meaningfully by honouring their commitments to themselves. This is the difference between hedonic wellbeing (pleasure-seeking, which is temporary and ultimately unsatisfying) and eudaimonic wellbeing (living according to values, which creates deep, lasting satisfaction).

The temporary discomfort of a workout or choosing a healthy meal might not feel pleasurable in the moment, but it contributes to a sense of living according to values, living with integrity. And that creates something more valuable than pleasure. It creates meaning. It creates self-respect. It creates what the Stoics called tranquillity. This does not mean the absence of struggle, but the presence of purpose and alignment with virtue.

As a coach, you can facilitate this shift from outcome-based to identity-based change by paying attention to language. When a client talks about their goals, you can reflect back to them in identity terms. “So it sounds like you’re becoming someone who prioritises their health.” “It sounds like you’re developing into a person who shows up for themselves consistently.” This isn’t just positive reinforcement, though it is that. It’s helping them build a new self-concept that will sustain behaviour long after the initial motivation fades.

And this matters more than most coaches realise, because the physiological changes we’re after such as improved resting heart rate, increased VO2 max, better body composition, muscle growth, strength gains, etc., all of these require consistent stimulus over time. They don’t happen through heroic single efforts. They happen through repeated signals that the body learns to adapt to. The person who walks ten minutes daily sends a more consistent adaptation signal than the person who does an intense workout once a month and then does nothing for weeks.

Think about how the body builds aerobic capacity. You stress the cardiovascular system with exercise, it adapts by building more capillaries, increasing mitochondrial density, and improving cardiac output. But this adaptation requires repeated stimulus. One hard workout followed by weeks of nothing doesn’t create adaptation. It creates a stress response that fades. But consistent, repeated stimulus, even if it’s moderate, creates lasting physiological change.

The same is true for muscle growth and strength. Progressive overload requires consistency. You need to be in the gym regularly enough that your muscles are receiving the signal to adapt, regularly enough that you’re practising the movement patterns that develop neuromuscular efficiency. The person who does two pushups every day is quite literally strengthening the neural pathways that support that movement pattern. After a few weeks, they’re doing more pushups because their nervous system has become more efficient at recruiting motor units.

Sleep quality, stress management, metabolic health, immune function, and longevity, all improve through consistent behaviours, not through occasional heroic efforts. The person with good sleep hygiene isn’t someone who occasionally has a good night’s sleep. They’re someone who has cultivated a consistent bedtime routine, a dark sleeping environment, and regular wake and sleep times. Their circadian rhythm is entrained because of consistency. Their cortisol patterns are healthy because stress management is a daily practice, not a weekend retreat they do once a year.

Common Coaching Mistakes That Undermine Behaviour Change

Now, I need to be honest with you about some mistakes I made early on, because I see newer coaches making the same ones, and I want to save you some pain. The biggest mistake is trying to change too much at once. You meet a client who’s excited and motivated, and you want to give them everything. Training plan, nutrition overhaul, sleep optimisation, stress management techniques, supplement protocols, etc. You think you’re being thorough, but what you’re actually doing is overwhelming them. You’re creating what I call behavioural debt. You’re making them take on too much change at once, which means they’ll eventually default on all of it.

Within two weeks, they’ve quit everything because it was too much to manage. Their prefrontal cortex couldn’t handle the decision fatigue. Their nervous system perceived the dramatic change as a threat. They burned through their limited willpower reserves and had nothing left. And now they feel like failures, which makes them less likely to try again.

The second mistake is not celebrating small wins. We’re so focused on the end goal that we don’t acknowledge the progress happening along the way. But progress is motivating. When someone does their tiny habit consistently for a week, that’s worth celebrating. When they make one better choice than they would have made a month ago, that’s worth noticing. These small acknowledgements compound just like the habits themselves. They build momentum and confidence. They deposit into the self-efficacy account. They reinforce the identity shift that’s happening.

The third mistake is mistaking compliance for commitment. Just because someone is doing what you tell them to do doesn’t mean they’re internally committed to the change. Maybe they’re people-pleasing. Maybe they’re trying to avoid disappointing you. But unless the motivation is coming from them, it won’t last. This is where motivational interviewing and autonomy-supportive coaching become essential. Your job is to help them find their own reasons for change, not to convince them to adopt yours. Give them choice. Give them rationale. Treat them as collaborators in their own change process, not as subordinates following orders.

And finally, we often ignore the emotional and psychological aspects of change. We treat it like a purely logical process. If someone knows what to do and has a plan, they should be able to do it. But humans are emotional creatures. Past experiences, current stress, relationships, and self-worth, all influence behaviour. If you’re not addressing the whole person, you’re missing crucial pieces of the puzzle.

Cognitive Behavioural Tools for Coaches

This is where techniques from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy become invaluable to your coaching practice. When a client says “I always fail at this,” that’s all-or-nothing thinking, a common cognitive distortion. When they say “I missed one workout, so I might as well give up for the week,” that’s catastrophising. You can help clients identify these automatic thoughts and challenge them with evidence. “Is it true you always fail? What about that time you stuck with it for three weeks? What about yesterday when you made a healthy choice even though you were tired?”

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy offers another powerful framework. ACT emphasises psychological flexibility, which is the ability to be present with discomfort while moving toward values. Instead of trying to eliminate uncomfortable thoughts and feelings, you learn to notice them without being controlled by them. This is called cognitive defusion: recognising that thoughts are just thoughts, not facts. “I’m having the thought that I can’t do this” rather than “I can’t do this.” That small linguistic shift creates space between you and your thoughts, which gives you choice about how to respond.

ACT also addresses something really important: the paradox that trying to control your internal experience often backfires. The more you try to suppress a craving, the stronger it gets. The more you fight anxiety, the more anxious you become. ACT calls this creative hopelessness, which is the realisation that control strategies don’t work, which then creates openness to a different approach. Instead of trying to feel motivated before you act, you act in alignment with your values and let motivation follow.

This connects to something fundamental in the Stoic philosophy that I find incredibly useful in coaching. Epictetus talked about the dichotomy of control, which is the idea that some things are within our control and some things aren’t, and wisdom lies in knowing the difference and focusing our energy accordingly. You can’t control outcomes. You can’t control whether you lose exactly twenty pounds by a certain date. You can’t control your genetics or how your body responds to training. But you can control your actions. You can control whether you show up for your workout. You can control whether you make a healthy choice at the next meal.

This shift is incredibly liberating for clients. When they stop trying to control outcomes and focus on controlling their actions, anxiety decreases and agency increases. They stop feeling like victims of their circumstances and start feeling empowered. Marcus Aurelius, writing in his private journal that became the Meditations, said something that applies perfectly to behaviour change: “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.” The obstacle isn’t interrupting your path. The obstacle is the path. The client who has to navigate stress, time pressure, family demands, and social pressure; they’re not failing because those obstacles exist, instead they’re developing the practical wisdom, what Aristotle called phronesis, to navigate those obstacles successfully. It is all long term skill acquisition.

Self-Compassion: The Essential Ingredient for Sustainable Change

This connects to something absolutely essential for sustainable behaviour change, something that’s central to the basics of behaviour change and habit formation: the role of self-compassion and how you handle failure. And I want to be clear, there will be failures. Your clients will fall off track. They’ll miss workouts. They’ll eat the whole pizza. They’ll go weeks without doing any of the things they committed to. This is not a question of if, it’s a question of when.

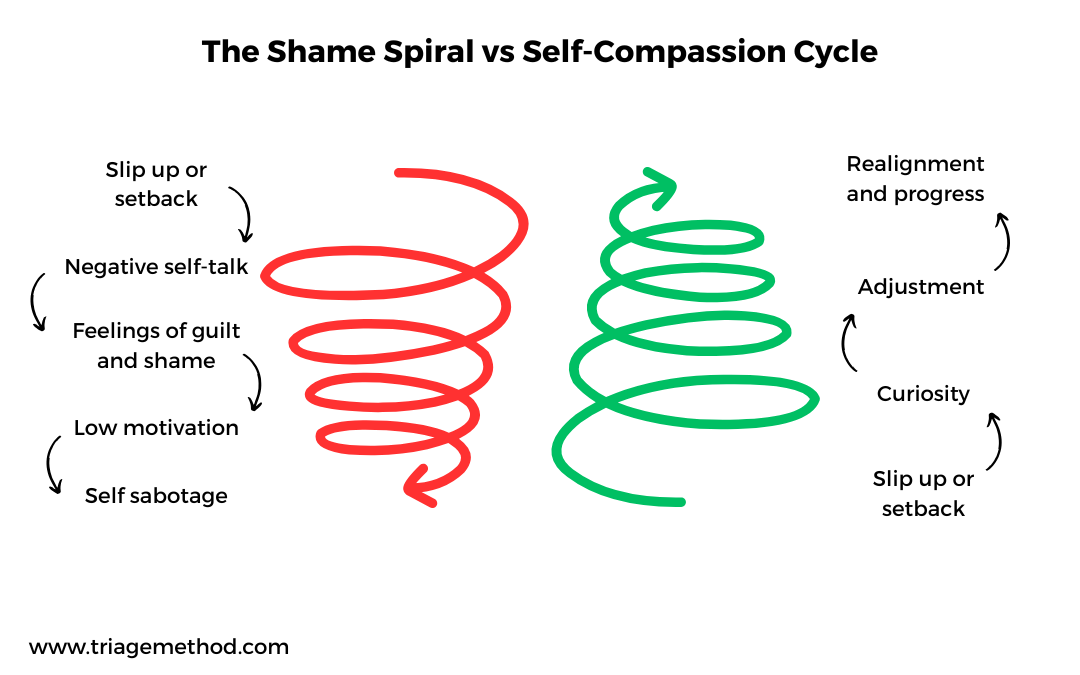

What separates clients who ultimately succeed from those who don’t usually isn’t whether they fail. It’s what happens after they fail. If the response to failure is shame, guilt, and self-criticism, it creates a downward spiral. They feel bad, which makes them want to escape the bad feeling, which often means avoiding the behaviour that made them feel bad in the first place. They stop showing up. They stop trying. The failure becomes permanent.

But if the response to failure is curiosity and self-compassion, something different happens. They can look at what happened without judgment. What were the circumstances? What got in the way? What can we learn from this? And then they get back to it. The failure becomes temporary, just information that helps them adjust their approach. This isn’t just nice psychology. It’s practical implementation science. Kristin Neff’s research on self-compassion shows that people who treat themselves kindly after setbacks are more likely to learn from them and try again.

As coaches, we set the tone for this. If you react to a client’s setback with disappointment or frustration, even subtle frustration, you’re reinforcing shame. But if you normalise it, if you make it clear that setbacks are an expected part of the process and an opportunity to learn, you give them permission to be imperfect. And that permission is what allows them to keep going.

The language I use when a client comes back after falling off track is something like: “Okay, so you didn’t do what you planned. That’s completely normal. Let’s figure out what got in the way and how we can make it easier next time.” No judgment. No lecture. Just problem-solving. This communicates that I’m on their team, not evaluating them, and that our work together is about learning and adjusting, not about being perfect.

This is where Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy’s ABC model can be useful. The Activating event (missed a workout), the Belief (“I’m a failure”), and the Consequence (giving up entirely). Most people jump straight from A to C without noticing B. But B is where the leverage is. You can help clients dispute irrational beliefs and develop more rational alternatives. “You missed a workout. That’s an event, not evidence of your character. What would be a more useful way to think about this?”

There’s also something called the Zeigarnik effect that’s worth understanding here too. Uncompleted tasks create mental tension. This is why starting something, even starting tiny, creates momentum toward completion. When a client comes back after falling off, the key isn’t to dwell on what they didn’t do. It’s to help them start again, even with the smallest action. Two pushups. One vegetable. A five-minute walk. Starting tiny releases the tension of the uncompleted task and rebuilds momentum.

Your Practical Coaching Framework: Putting It All Together

So, how do you actually put all of this together into a coherent coaching approach? Let me give you a framework that synthesises everything we’ve talked about, and that incorporates the basics of behaviour change and habit formation in a way you can actually apply. When you start working with a new client, the first thing you do is assess their readiness for change. What stage are they in? Are they contemplating, preparing, or ready for action? Your approach needs to match their stage, or you’ll create resistance.

Use open-ended questions to explore their relationship with the behaviour. “What have you been thinking about regarding your health?” “What would be good about making this change?” “What concerns do you have?” Listen for their reasons, not your reasons. Reflect back what you hear. Affirm their autonomy. This isn’t just nice relationship-building. This is creating the psychological foundation for change.

Once you understand where they are, you help them start small. Identify one tiny behaviour that moves them in the right direction. Not five behaviours. One. And make it so small that it feels almost too easy. This is your minimum viable habit. This creates consistency, which builds the neural pathways through Hebbian learning. It creates mastery experiences, which build self-efficacy. It creates proof that they’re the kind of person who does this thing, which shifts identity.

Engineering Environments and Systems

Throughout this process, you’re helping them engineer their environment to support the change. This is practical choice architecture. What can you make easier? What can you make harder? How can we set up the physical and social environment so that the desired behaviour is the path of least resistance? This might mean meal prepping, setting up a home gym space, joining a group, changing their commute, removing temptations, creating visual cues, or whatever makes sense for that person and that behaviour.

And this is where understanding systems thinking becomes crucial. Behaviours don’t exist in isolation. Sleep affects stress levels, stress affects food choices, food choices affect energy, energy affects exercise adherence, and exercise affects sleep quality. You’re not coaching isolated variables. You’re intervening in a complex system. Sometimes the highest-leverage point isn’t the obvious one. Sometimes improving sleep is the key that unlocks everything else because it improves prefrontal cortex function, which improves decision-making, which improves all downstream behaviours.

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus is relevant here too. The embodied habits and dispositions we develop from our social environment shape us profoundly. A client’s struggles aren’t just individual. They’re shaped by class, culture, family patterns, and social networks. This adds compassion and context without removing agency. You’re helping them become conscious of these influences so they can make deliberate choices about which patterns to keep and which to change.

And speaking of social networks, there’s strong research showing network effects in health behaviours. You become like the five people you spend the most time with. This isn’t metaphorical. It’s measurable in obesity research, happiness research, exercise adherence research, and even longevity research. Helping clients build supportive social networks isn’t just encouragement. It’s intervention work. Maybe they join a workout group. Maybe they find an accountability partner. Maybe they distance themselves from relationships that undermine their health. The social environment shapes behaviour just as powerfully as the physical environment.

Focus on Process, Not Just Outcomes

At the same time, you’re working on the identity level. You’re helping them see themselves as someone who does this thing. You’re using language that reinforces this new identity. “You’re becoming someone who prioritises their health.” “You’re developing into a person who follows through on commitments to themselves.” You’re noticing and celebrating when their actions align with who they’re becoming. This creates internal motivation that outlasts any external motivation you could provide.

And you’re tracking the process, not just the outcomes. Yes, you care about whether they improve their body composition, increase their VO2 max, build strength, reduce their resting heart rate, improve their sleep quality, and manage their stress better. But day to day, you’re paying attention to consistency with the behaviour. Did they do the thing they said they’d do? That’s what matters most because that’s what leads to the outcome.

When you focus on process, you’re measuring things the client has direct control over, which builds agency and reduces anxiety about things they can’t control. This is the Stoic dichotomy of control applied practically. You can control your actions. You can’t control exactly how your body responds or when results show up. Focusing on what you control creates both better psychological outcomes and, paradoxically, better physical outcomes because you’re not creating the stress and anxiety that interfere with adaptation.

I also recommend using implementation intentions/”if-then” plans. These are specific plans that bypass decision-making in the moment. “If it’s 7 AM, then I will do my two pushups.” “If I’m making dinner, then I will include one vegetable.” “If I feel stressed, then I will take five deep breaths.” Research shows these dramatically increase follow-through because you’re not relying on in-the-moment willpower. You’ve pre-decided. When the cue happens, the behaviour follows automatically.

The Iterative Approach: Variation, Selection, and Adaptation

Finally, you’re constantly adjusting based on feedback. This isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it situation. You’re checking in regularly about what’s working and what isn’t. You’re troubleshooting barriers as they come up. You’re making the plan easier or harder based on how they’re actually doing, not how you think they should be doing. This iterative approach is what allows you to find the right level of challenge for each person at each stage of their journey.

Think of this like running n=1 experiments. Each client is their own study, and you’re collecting data on what works specifically for them. You try small experiments, observe the results, keep what works, adjust what doesn’t, and iterate. This removes perfectionism from the equation. It’s experimental. It’s exploratory. It’s curious. It takes the moral weight off failure and reframes it as information. You’re not implementing a universal protocol, you’re discovering what protocol works for this particular person in their particular context.

The beautiful thing about mastering these principles, about truly understanding the basics of behaviour change and habit formation at this deeper level, is that they work for everyone. Whether you’re coaching a complete beginner or an elite athlete, whether someone wants to lose weight or build muscle or just feel better in their body, whether they’re dealing with chronic stress or poor sleep or low energy, the fundamentals of behaviour change remain the same. The specific behaviours will differ, but the process of establishing new habits and breaking old ones follows these same patterns.

Practice These Principles in Your Own Life First

I want to encourage you to be patient with yourself as you develop these skills. Becoming a world-class coach isn’t about memorising information. It’s about developing the ability to see what’s really happening with someone and meet them there. That takes time and practice. You’re going to make mistakes. You’re going to have clients who don’t succeed despite your best efforts. That’s part of the learning process. The coaches I know who are the absolute best at this work are the ones who stayed curious, who kept learning from every client, who were willing to adjust their approach when something wasn’t working.

And something I wish someone had told me earlier is that you should practice these principles in your own life first. Pick something in your own life you want to change and apply everything we’ve talked about. Assess your readiness. Start small with a minimum viable habit. Engineer your environment. Work on identity. Use implementation intentions. Practice self-compassion when you mess up. Notice what’s hard about it and what helps. That lived experience will make you a better coach than any amount of theoretical knowledge.

Because this will show you that you have to deal with a paradox to accomplish behaviour change and that is that you have to accept yourself fully as you are before you can change. Shame and self-rejection don’t motivate sustainable change. They paralyse. But self-acceptance creates the psychological safety to take risks, to try new behaviours, to fail and get back up. This is true for you, and it’s true for your clients. You can’t effectively guide someone through behaviour change if you’re judging them for needing to change. You can’t help someone develop self-compassion if you don’t have it for yourself.

There’s another paradox worth understanding too. Trying too hard often backfires, but making things easy often works better. We’ve been taught that transformation requires suffering, that “no pain, no gain,” that if it’s not hard, it doesn’t count. But the basics of behaviour change and habit formation teach us something different. The changes that last are often the ones that feel almost too easy at first. The ones that slip under your threat detection radar. The ones that build so gradually you barely notice until suddenly you realise you’ve become a different person.

This connects to something pragmatist philosopher William James discussed. He said that truth is what works in practice, not what sounds good in theory. You’re not looking for the “perfect” program that exists in textbooks. You’re finding what actually functions for this person in their actual life with their actual constraints and capabilities. This is practical wisdom, phronesis, knowing not just what to do, but when, how much, and in what manner for this specific person in this specific context.

What Makes World-Class Coaching: Understanding The Basics of Behaviour Change and Habit Formation

The coaches who really excel at this work are the ones who understand that behaviour change isn’t about forcing people to do things they don’t want to do. It’s about helping them become who they want to become, one small, sustainable step at a time. It’s about creating the conditions where change becomes natural rather than forced. And it’s about being a steady, compassionate presence as they navigate the inevitable ups and downs of transformation.

This is what separates good coaches from world-class ones. Not how much you know about programming or nutrition science, though that matters. Not how many certifications you have or how impressive your Instagram is, though those can matter too. But how well you understand the basics of behaviour change and habit formation, how skillfully you can meet people where they are and guide them forward without pushing them beyond their capacity. How well you understand that you’re not just training bodies, you’re helping people develop excellence of character (arete), through the practice of health-supporting behaviours.

Master this, and you’ll have clients who don’t just achieve their goals but maintain them, who develop genuine confidence in their ability to change, who see you as the person who helped them become who they wanted to be. They won’t just have lower resting heart rates and improved VO2 max and better body composition, though they’ll have those too. They’ll have developed the practical wisdom to navigate health challenges for the rest of their lives. They’ll have built self-trust through following through on commitments to themselves. They’ll have experienced what it feels like to live with integrity, to align their actions with their values, to practice eudaimonia (human flourishing).

And that’s the kind of coaching that creates lasting impact. Not just temporary results that disappear when someone stops working with you, but genuine transformation in how someone relates to themselves and their health. That’s what I want for you. That’s what your clients deserve. And that’s what becomes possible when you truly understand the basics of behaviour change and habit formation, not just as theory, but as lived practice that you embody and teach with every interaction.

Having said all of that, you do still need a working model of physiology, nutrition and training to actually get results. So, for those of you ready to take the next step in professional development, we also offer advanced courses. Our Nutrition Coach Certification is designed to help you guide clients through sustainable, evidence-based nutrition change with confidence, while our Exercise Program Design Course focuses on building effective, individualised training plans that actually work in the real world. Beyond that, we’ve created specialised courses so you can grow in the exact areas that matter most for your journey as a coach.

If you want to keep sharpening your coaching craft, we’ve built a free Content Hub filled with resources just for coaches. Inside, you’ll find the Coaches Corner, which has a collection of tools, frameworks, and real-world insights you can start using right away. We also share regular tips and strategies on Instagram and YouTube, so you’ve always got fresh ideas and practical examples at your fingertips. And if you want everything delivered straight to you, the easiest way is to subscribe to our newsletter so you never miss new material.

References and Further Reading

Baladron J, Hamker FH. Habit learning in hierarchical cortex-basal ganglia loops. Eur J Neurosci. 2020;52(12):4613-4638. doi:10.1111/ejn.14730 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32237250/

Seger CA, Spiering BJ. A critical review of habit learning and the Basal Ganglia. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:66. Published 2011 Aug 30. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00066 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3163829/

Smith KS, Graybiel AM. Habit formation. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(1):33-43. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/ksmith https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4826769/

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191-215. doi:10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/847061/

Lawrance L, McLeroy KR. Self-efficacy and health education. J Sch Health. 1986;56(8):317-321. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1986.tb05761.x https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3534459/

Williams DM, Rhodes RE. The confounded self-efficacy construct: conceptual analysis and recommendations for future research. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(2):113-128. doi:10.1080/17437199.2014.941998 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4326627/

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38-48. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10170434/

Norcross JC, Krebs PM, Prochaska JO. Stages of change. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):143-154. doi:10.1002/jclp.20758 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21157930/

Neff KD. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023;74:193-218. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35961039/

Germer CK, Neff KD. Self-compassion in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(8):856-867. doi:10.1002/jclp.22021 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23775511/

Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537. doi:10.1037/a0016830 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2759607/

Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305-312. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15826439/

Schweiger Gallo I, Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: a look back at fifteen years of progress. Psicothema. 2007;19(1):37-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17295981/

Wieber F, Thürmer JL, Gollwitzer PM. Promoting the translation of intentions into action by implementation intentions: behavioral effects and physiological correlates. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:395. Published 2015 Jul 14. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00395 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4500900/

Orbell S, Hodgkins S, Sheeran P. Implementation Intentions and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23(9):945-954. doi:10.1177/0146167297239004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29506445/

Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(605):664-666. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659466 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3505409/

Lally P, Wardle J, Gardner B. Experiences of habit formation: a qualitative study. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16(4):484-489. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.555774 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21749245/

Mertens S, Herberz M, Hahnel UJJ, Brosch T. The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(1):e2107346118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2107346118 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34983836/

Mertens S, Herberz M, Hahnel UJJ, Brosch T. The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(1):e2107346118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2107346118 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8740589/