The Fogg Behaviour Model taught me that I was teaching behaviour change completely backwards. If you’re relying on motivation to carry your clients through, you’re likely making the same mistake I was making. We’ve been trained to think that if we can just inspire people enough, show them enough transformation photos, explain the health consequences clearly enough, they’ll finally do the thing. But motivation is like trying to build a house on quicksand. It shifts. It disappears. And it actually has nothing to do with how much your client wants the result.

What changed everything for me was stumbling onto the Fogg Behaviour Model. It wasn’t complicated or revolutionary in some flashy way, but it was so obvious and helpful that once I saw it, I couldn’t believe I’d been coaching without it. BJ Fogg’s behaviour model gave me a framework that actually explained why behaviours happen, or don’t. And more importantly, it showed me that when my clients weren’t following through, it usually wasn’t a motivation problem at all.

We’ve been trained to think that if we can just inspire people enough, show them enough transformation photos, explain the health consequences clearly enough, they’ll finally do the thing. This is the default coaching paradigm most of us inherit: the motivation-first model. It seems logical that if someone wants something badly enough, they’ll do what it takes to get it. So when clients don’t follow through, we assume they don’t want it badly enough. We question their commitment. We wonder if we explained the benefits clearly enough. We give another pep talk, post another inspirational quote, share another success story…

But motivation is like trying to build a house on quicksand. It shifts. It disappears. And it really does have nothing to do with how much your client wants the result. I’ve had clients who desperately wanted to change (I mean tears in their eyes, genuine commitment), and they still didn’t do the behaviours. Not because they were lazy. Not because they didn’t care. But because I was asking them to build on an unstable foundation.

The motivation-first approach creates a vicious cycle:

Client gets motivated → Commits to ambitious plan → Motivation inevitably fades → Client doesn’t follow through → Coach (and client) blame lack of motivation → Coach tries to boost motivation again → Repeat.

We’re solving for the wrong variable. We’re treating motivation as the problem when it’s actually just a symptom of poor design.

Most of my clients had plenty of motivation. They wanted results. They cared deeply. What they didn’t have was a behaviour that matched their current ability level, or a reliable prompt to trigger that behaviour at the right moment. The Fogg Behaviour Model revealed that I’d been diagnosing the problem incorrectly for years. I’d been seeing motivation problems everywhere when I was actually looking at ability problems and prompt problems.

This realisation was humbling. How many clients had I failed because I kept trying to boost their motivation when what they actually needed was a smaller behaviour or a better prompt? How many people had I made feel inadequate and like they just weren’t trying hard enough, when the real issue was my design?

The shift from motivation-based coaching to behaviour design isn’t just a new technique. It’s a completely different paradigm. It changes how you see client struggles, how you structure programs, how you measure success, and fundamentally, how you understand your role as a coach. You stop being someone who tries to maintain your clients’ motivation and start being someone who designs behaviours that don’t need high motivation to succeed.

TL;DR

Behaviour change fails when it’s built on motivation. Motivation is volatile and uncontrollable; relying on it guarantees drop-off. The real problem when clients don’t follow through is almost never desire or motivation; it’s poor behaviour design.

The Fogg Behaviour Model (B = MAP) shows that behaviour only happens when Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt align in the same moment. When something doesn’t happen, the fix isn’t a pep talk, it’s diagnosing which element was missing.

In practice, this means:

- Design for low motivation, not peak enthusiasm.

- Increase ability by making behaviours absurdly easy (easy beats “try harder”).

- Use strong prompts, especially action-based anchors tied to existing routines.

- Celebrate immediately, because positive emotion wires habits into automaticity.

Tiny habits work because they sit above the action line, repeat easily, and create momentum. Identity changes after consistent action, not before it.

For coaches, the shift is foundational: stop motivating, start designing. When behaviour is well designed, motivation almost becomes optional, and change becomes inevitable.

Table of Contents

- 1 TL;DR

- 2 The Fogg Behaviour Model: The Formula That Explains Everything

- 3 Understanding the Action Line: When Behaviour Actually Happens

- 4 The Approach That Actually Works

- 5 Join 1,000+ Coaches

- 6 The Tiny Habits Playbook: How to Actually Apply the Fogg Behaviour Model

- 7 Scaling Without Breaking: When and How to Grow

- 8 The Pitfalls That Will Kill Your Results (Even When Using the Fogg Behaviour Model)

- 9 When Behaviours Still Aren’t Happening: The Fogg Behaviour Model Diagnostic

- 10 Why the Fogg Behaviour Model Makes You a Better Coach (Not Just More Effective)

- 11 Your Action Plan: Implementing the Fogg Behaviour Model Tomorrow

- 12 The Counterintuitive Truth About Change

- 13 Author

The Fogg Behaviour Model: The Formula That Explains Everything

Here’s the whole model:

B=MAP

Behaviour happens when Motivation, Ability, and Prompt converge at the same moment.

That’s it. The Fogg Behaviour Model distils human behaviour into this elegant equation. No behaviour occurs without all three elements present at the exact same time. Not kind of present. Not “I’ll remember later.” Right there, right then, in that specific moment.

And here’s why the Fogg Behaviour Model matters more than any workout program or meal plan you’ll ever write: it gives you a diagnostic tool. When your client doesn’t do the thing they said they’d do, you don’t have to guess or give another pep talk. You just look at which element was missing. You become a behaviour detective, not a motivational speaker.

This is what Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein call choice architecture in their work on behavioural economics; you’re designing the environment and decision-making context to make desired behaviours easier. The Fogg Behaviour Model is choice architecture for habit formation. You’re not manipulating your clients; you’re engineering the conditions where success becomes inevitable.

Let me break down each piece, because understanding the Fogg Behaviour Model is going to change how you coach forever.

Motivation: The Element You’ve Been Overestimating

Motivation is the desire to do the behaviour. And yes, it matters. But here’s what nobody tells you in your coaching certification: motivation is the most unreliable element in the entire equation. The Fogg Behaviour Model deliberately positions motivation as just one piece, not the whole puzzle, because BJ Fogg understood something most coaches miss.

Think about your own day. You wake up ready to conquer the world. By 2 PM, you’re face-down in a bag of crisps, questioning all your life choices. By evening, you’ve rallied, and you’re planning tomorrow’s perfect routine. That’s motivation waves, and they’re completely normal. They’re not a character flaw. They’re human biology shaped by millions of years of evolution.

Our brains didn’t evolve for long-term abstract goals like “be healthier in twenty years.” We evolved for immediate threats and immediate rewards in small tribal groups. Mismatch theory explains why modern behaviour change is so hard, we’re using Stone Age brains in a Space Age world. The Fogg Behaviour Model works WITH our evolutionary wiring instead of fighting against it.

The ancient Stoics understood this intuitively too. Epictetus taught the dichotomy of control: we don’t control our feelings, but we control our responses to them. We don’t control whether motivation shows up tomorrow morning, but we absolutely control how we design our habits. The Fogg Behaviour Model is Stoicism for behaviour change; focus on what you can control (the design) and accept what you can’t (fluctuating motivation).

Your client who was pumped about meal prep on Sunday? By Wednesday night when they’re exhausted from work, and the kids are losing their minds, that motivation is gone. Vanished. And all your inspirational quotes on Instagram aren’t going to bring it back in that moment.

So, if you design a habit that requires high motivation to execute, you’re designing for failure. Because high motivation doesn’t stick around. It’s a fair-weather friend. In cognitive behavioural therapy terms, believing you’ll always feel motivated is a cognitive distortion, specifically, emotional reasoning. “I feel motivated now, so I’ll feel motivated later.” It’s simply not true.

So instead of asking “How do I keep my clients motivated?”, we need to ask a better question: “How do I design habits that work even when motivation is low?”

Because those low-motivation days are not the exception. They’re going to be a huge chunk of your client’s life. If your coaching strategy falls apart when motivation dips, you don’t have a strategy. You have a hope. And hope, as any good strategist will tell you, is not a plan.

Ability: The Game-Changer Nobody Talks About

Ability is how easy or hard the behaviour is to do. And this is where the Fogg Behaviour Model fundamentally shifts how we think about change.

Ultimately, when a behaviour is hard, even sky-high motivation won’t save it. You can want something desperately and still not do it if it’s too difficult in that moment. This isn’t weakness. This is reality. The Fogg Behaviour Model shows us that motivation and ability exist in a relationship, they’re not independent variables.

I learned this the hard way with a previous client. This client swore he was going to start running. He’d been an athlete in secondary school, loved the idea of getting back into it, and had all the motivation in the world. I mapped out a beginner running plan. He didn’t do it. Not even once.

Old me would’ve questioned his commitment. New me, armed with the Fogg Behaviour Model, asked a different question: “Was it too hard?” And once we actually talked through it, the barriers came tumbling out. His knees hurt. He didn’t know what to wear. He felt self-conscious running in his neighbourhood. He wasn’t sure about the route. The whole thing was wrapped in so much friction that his motivation didn’t stand a chance.

This is what Roy Baumeister’s research on decision fatigue reveals: every decision, every obstacle, every point of friction costs willpower. And willpower is a finite resource (or at least it feels like it). The Fogg Behaviour Model conserves willpower by removing friction rather than demanding more self-control.

So we made it easier. Absurdly easier. We started with a five-minute walk around his neighbourhood after dinner. That’s it. Not running. Walking. For five minutes. In whatever he was already wearing.

He did it that night. And the next night. And the night after that.

“Make it easier” beats “try harder” every single time. This is the ability-first approach, and it’s the opposite of what most of us were taught. We think pushing clients harder shows that we believe in them. But making things easier actually shows we understand them. In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) terms, we’re practising psychological flexibility: accepting that internal states fluctuate and designing around that reality rather than fighting it.

Aristotle knew this. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he wrote about hexis, which suggests that character states are formed through repeated action. He understood that we don’t become virtuous by wanting to be virtuous. We become virtuous by performing virtuous acts until they become our character. “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.” The Fogg Behaviour Model is Aristotle’s virtue ethics made practical: make the action small enough to repeat, and character follows.

Prompts: The Secret Weapon You’re Probably Ignoring

The third element is the prompt (also often called triggers). This is the cue that triggers the behaviour in the moment. And honestly, this is the most overlooked element when people try to apply the Fogg Behaviour Model, and it’s the secret weapon of coaches who get consistent results.

A prompt is what reminds your client to do the behaviour at the exact moment they need to do it. Not five minutes later. Not when they remember. Right then. Without a prompt, even high motivation and high ability go nowhere. The behaviour just sits there, waiting for a trigger that never comes.

Think of it like this: you can have a loaded gun with perfect aim, but without pulling the trigger, nothing happens. The prompt is the trigger. The Fogg Behaviour Model requires all three elements simultaneously. This isn’t a linear process; it’s a convergence.

There are three types of prompts, and understanding the difference matters tremendously when implementing the Fogg Behaviour Model with real clients.

Person prompts are cues from other people. Your check-in text, an accountability partner, a workout buddy. These can work, but they’re fragile. They depend on someone else being available and paying attention. In systems thinking terms, you’re creating a dependency that introduces a point of failure.

Context prompts are cues from the environment. Gym clothes laid out the night before. Pre-portioned meals in the fridge. Running shoes by the door. These are more reliable than person prompts because they’re always there, but they still require your client to be in the right place at the right time. This is nudge theory in practice; you’re restructuring the environment to make the desired behaviour easier.

Action prompts are the gold standard of the Fogg Behaviour Model. These are cues from routines your client already does every single day without thinking. After I pour my coffee. After I brush my teeth. When I sit down at my desk. When I get home from work.

Action prompts are so powerful because they hijack behaviours that are already automatic. Your client doesn’t forget to brush their teeth. They don’t need motivation to pour their morning coffee. These anchors are already wired into the basal ganglia (the part of your brain that handles automatic behaviours). When you attach a new tiny habit to one of these existing routines using the Fogg Behaviour Model, you’re not asking your client to remember something new. You’re piggybacking on neural pathways that have been reinforced thousands of times.

This is Hebbian learning in action: neurons that fire together, wire together. The existing routine and the new tiny habit begin firing together, and with repetition, they become a single unified pattern. Your brain literally rewires itself.

This is why “I’ll go to the gym after work” often fails; “after work” isn’t specific enough and isn’t tied to a concrete action. But “After I take off my work shoes, I’ll change into my gym clothes” has a built-in trigger. The moment you remove your shoes, the prompt fires. It’s specific, concrete, and anchored to something that happens every single day.

Most coaches I talk to are trying to help their clients remember to do new habits. Better coaches, those who truly understand the Fogg Behaviour Model, help their clients with strong action prompts that remove the need for memory, decision-making, or motivation. It makes the behaviour feel inevitable.

Understanding the Action Line: When Behaviour Actually Happens

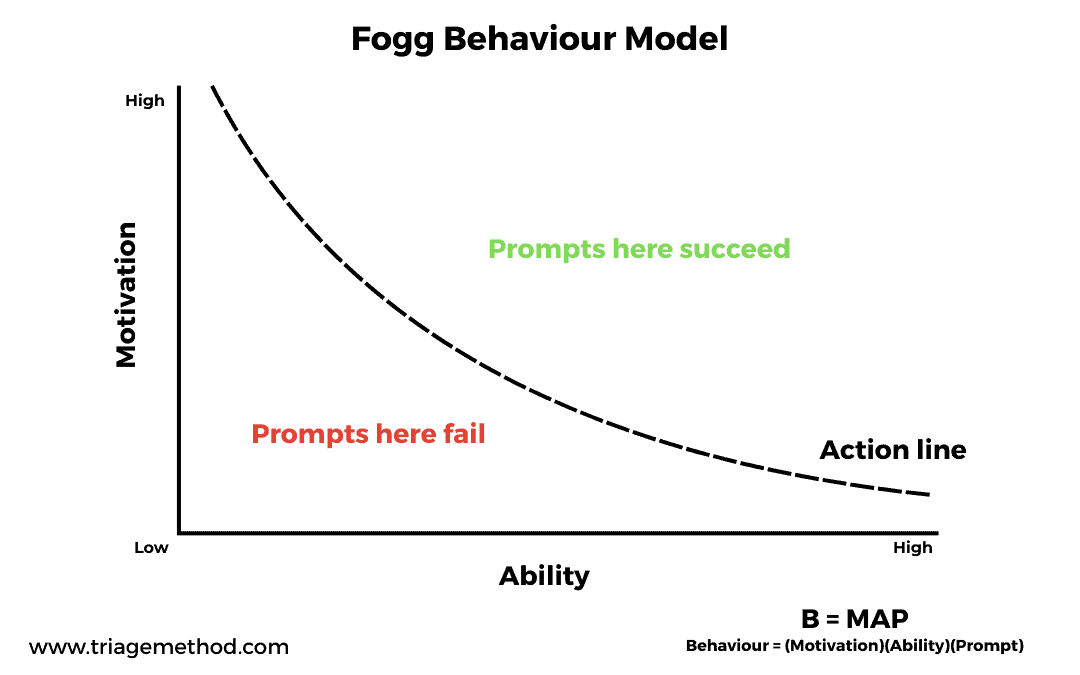

The Fogg Behaviour Model can be explained visually, and I personally find this most helpful in understanding it, especially as it applies to actually putting it into practice.

Motivation runs up the vertical axis, ability runs along the horizontal axis. The action line curves across the graph. Any behaviour that sits above that line (meaning it has enough motivation AND enough ability, plus a prompt shows up) happens automatically. Any behaviour below the line generally won’t happen, no matter how much willpower your client throws at it.

This is your diagnostic tool in real-time. When a client isn’t following through, you’re not guessing anymore. You’re just looking at where their behaviour sits relative to that action line. The Fogg Behaviour Model helps to make the invisible visible, and that really is a game-changer for coaching.

Let’s say your client wants to do a 30-minute workout before work. If their motivation is low (they’re tired, stressed, not feeling it) and the ability is also low (30 minutes is a lot, they have to get dressed, drive to the gym, figure out what to do), that behaviour is way below the action line. A prompt won’t help. It doesn’t matter if you text them every morning. The behaviour simply isn’t going to happen.

So you have a choice: boost motivation or increase ability. And what I’ve learned after working with hundreds of clients and teaching the Fogg Behaviour Model to dozens of coaches is that ability wins almost every time. So, your focus should mostly be on improving ability, not motivation.

This is because you have very little control over motivation. You can inspire someone temporarily, sure. But you can’t sustain it. Motivation is internal and fluctuating. Ability is something that you can actually design. You can make behaviours easier. You can remove friction. You can shrink the habit until it rises above that action line.

This is what Donella Meadows called finding the leverage point in complex systems. Small interventions at the right leverage point create disproportionate change. When you use the Fogg Behaviour Model to identify that a behaviour is below the action line, you’ve found your leverage point. You don’t push harder. You redesign.

When I finally understood the Fogg Behaviour Model deeply, I stopped seeing client struggles through the lens of compliance or laziness. Those words effectively disappeared from my vocabulary. Instead, I started asking: “Is this behaviour above or below their action line right now, given their current motivation and the difficulty of what I’m asking them to do?”

Most of the time, I’d been asking for behaviours that were below the line. And then I was surprised when they didn’t happen. The problem wasn’t my clients. The problem was my design.

In Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT), Albert Ellis talked about “musturbation”, which is the irrational belief that things must be a certain way. Many coaches (myself included, historically) engage in musturbation about client behaviour: “They must feel motivated. They must do a real workout. It must look impressive.” The Fogg Behaviour Model demolishes these irrational demands. It replaces “must” with “what works.” It is core to pragmatic coaching. We don’t focus on the way we think things must be set up; we focus on what actually works in practice.

The Approach That Actually Works

Generally, when a client isn’t following through, we give them a pep talk. We show them transformation photos. We explain the health consequences of not changing. We try to boost their motivation. That’s the way most of us think we can generate success with our clients. It’s what we have all been taught.

And it doesn’t work. Or it works for a few days, until the motivation fades again, and then we’re back where we started. This is the definition of insanity; doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results. The Fogg Behaviour Model offers a different path entirely.

In Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, there’s a fundamental principle of position before submission. You establish a dominant position before attempting the finish. Going for a submission without position fails almost every time. In coaching, applying the Fogg Behaviour Model means the tiny habit is the position; the big result is the submission. Trying to finish without position (e.g. asking clients to “work out five days a week” before establishing the foundational habit), fails for the same reason.

The ability-first approach flips this completely: make the behaviour so easy they can do it on their worst day.

Not their best day. Not when they’re motivated. Their worst day. The day when everything goes wrong, they’re exhausted, stressed, and barely holding it together. If the habit can survive that day, it’ll survive anything.

I had a client named Jennifer who wanted to start strength training. She had a gym membership she wasn’t using. Old me would’ve designed a three-day split, explained the benefits, and sent her off with encouragement. Current me would ask: “What’s the smallest version of this that you could do on your absolute worst day?”

She thought about it. “I could do one set of squats in my living room.”

“Not three sets?”

“Probably not. One, though? Yeah, I could do one.”

So that’s what we started with. After she made her morning coffee, she’d do one set of squats. Not a workout. Not even ten minutes. One set. Maybe 30 seconds.

She did it every day for three weeks. And once the tiny habit became automatic, she naturally wanted to do more. Success breeds momentum. This is a positive feedback loop; success creates positive emotion, which increases motivation, which makes expanding easier. We added another set. Then we added some push-ups. Within two months, she had a full morning routine. But it started with one set of squats.

This is what your ego as a coach might resist. One set doesn’t sound impressive. It doesn’t look good on a program template. It’s not something you can post about. But it works. And impressive-sounding programs that nobody actually does, don’t work.

The pragmatist philosopher William James wrote: “Truth is what works.” The Fogg Behaviour Model is radically pragmatic. It doesn’t care about ideals or shoulds, only what actually produces behaviour. James also said: “The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.” In coaching: overlook the impressive-sounding program; focus on what works.

The paradox that the Fogg Behaviour Model reveals to us is that the smaller the commitment, the bigger the transformation. This seems backwards to our achievement-oriented minds, but it’s true. One push-up sounds ridiculous. But one push-up every day for a year is 365 push-ups more than zero. And more importantly, that one push-up can actually serve as the foundation for everything else.

The Tiny Habits Playbook: How to Actually Apply the Fogg Behaviour Model

The practical framework I use with every single client now, is built directly from the Fogg Behaviour Model.

Start absurdly small. Not just small. Absurdly small. Forget “workout five days a week.” Think “do one push-up after I brush my teeth.” Think “add one vegetable to dinner.” Think “walk to the end of the driveway and back.”

I know what you’re thinking. That’s ridiculous. That won’t make a difference. What I’ve learned from applying the Fogg Behaviour Model for years is that the size of the habit has almost nothing to do with whether it creates lasting change. What matters is whether it becomes automatic. And tiny habits become automatic. Big habits require motivation, which we’ve already established is unreliable.

In neuroscience terms, habits move from conscious processing (prefrontal cortex) to automatic processing (basal ganglia) through repetition. But the key is that tiny habits make this transition faster because there’s less cognitive load to overcome. Each time you have to decide, plan, or exert willpower, you’re keeping the behaviour in conscious processing. The Fogg Behaviour Model’s emphasis on tiny habits accelerates the transition to automaticity.

This also addresses the Zeigarnik Effect, which is the psychological principle that unfinished tasks create mental tension. When your tiny habit is so small that you always complete it, you get closure. That completion is psychologically satisfying. Meanwhile, clients who start with ambitious habits rarely complete them, leaving a trail of psychological tension and reinforcing an identity of someone who doesn’t follow through. And as we have discussed elsewhere, identity change is super important to long term success.

Use anchors, not alarms. Stop having clients set reminders on their phone. Stop relying on calendar notifications. Those get ignored or dismissed, especially when motivation is low. This is where many people misapply the Fogg Behaviour Model; they understand the need for prompts but choose unreliable ones.

Instead, help them attach new habits to existing routines using the formula BJ Fogg teaches: “After I _____, I will _____.”

After I pour my morning coffee, I’ll do ten squats. After I brush my teeth at night, I’ll lay out my gym clothes. After I sit down at my desk, I’ll drink a glass of water.

The existing routine is the prompt. It fires automatically. Your client doesn’t have to remember or decide or muster motivation. The anchor does the heavy lifting. This is implementation intentions research (Peter Gollwitzer’s work) meeting the Fogg Behaviour Model; if-then planning doubles follow-through rates because it removes the need for in-the-moment decision-making.

An analogy I always use to help explain this is that in boxing, every great combination starts with the jab. The jab seems insignificant, it’s not a knockout punch, but it sets up everything else. Tiny habits anchored to existing routines are your jab. They establish position. They create openings. Coaches who try to throw power punches without establishing the jab get countered. Apply the Fogg Behaviour Model correctly, and you’re using your jab to actually get the clients to succeed. You don’t want to be the coach who has the huge power punch, but who can never get it off because they don’t jab. You want to be the coach who sets things up with intelligent and strategic use of the jab.

Celebrate immediately. This is the piece most coaches skip when they first learn the Fogg Behaviour Model, and it’s absolutely critical. The neuroscience is clear: how your client feels after doing the behaviour matters more than the behaviour itself.

If they do their one push-up and feel nothing, or worse, feel like it wasn’t enough, the habit won’t wire in. But if they do their one push-up and feel successful, proud, accomplished (even for two seconds), well, that positive emotion strengthens the neural pathway. They’re more likely to do it tomorrow.

This is Hebbian learning again: neurons that fire together, wire together. But it’s not just the behaviour that needs to fire, it’s the behaviour plus the positive emotion. The celebration creates the emotional component that makes the neural pattern stick.

So, I would recommend that you teach your clients to actually celebrate their wins, and this includes their actions. It can be anything. A fist pump. Saying “Yes!” out loud. A little victory dance. It sounds silly, but it works.

Jean-Paul Sartre said “existence precedes essence”; we become through our actions, not through our intentions. Your client doesn’t become a “workout person” by wanting it; they become it by doing one push-up daily until the identity emerges. The Fogg Behaviour Model is existentialist in its core insight: you create yourself through design choices and repeated action, not through abstract self-concepts or wishful thinking.

Scaling Without Breaking: When and How to Grow

Okay, so your client’s doing their tiny habit consistently. They’re celebrating. It’s becoming automatic. Now what?

This is where most coaches, and most clients, mess it up. The habit is working, so naturally, we want to do more. We want to go big. And we end up killing the momentum. This violates the core principle of the Fogg Behaviour Model: you’re not training motivation, you’re building automaticity.

The critical question is: when is a client ready to grow their habit?

Here are the signs I look for:

- They’re doing it without thinking about it.

- They’ve been consistent for at least two weeks, usually longer.

- There’s positive emotion attached; they feel good doing it, not like it’s a chore.

If those things aren’t true, it’s too early to scale. The behaviour is still below the action line threshold for automaticity. When they are ready, I use what BJ Fogg calls the “Shine and Expand” approach. Let the habit root first, then gradually increase. Never force premature growth.

Remember Jennifer with her one set of squats? I didn’t suggest she add more until she’d done that one set every day for three weeks. When I finally asked if she wanted to expand, she’d already been doing two sets on her own for a few days. The habit was so automatic that expanding felt natural, not forced. It had moved fully into her basal ganglia. The decision to expand was effortless because the foundation was solid.

Now, there’s a difference between expanding the behaviour itself versus adding a new tiny habit. Expanding means making the current habit bigger; one set becomes two sets, five-minute walk becomes ten minutes. Adding means starting a completely new tiny habit with its own anchor and celebration. I usually suggest adding rather than expanding, especially for clients with packed schedules. Multiple small, automatic habits are more resilient than one big habit that requires a lot of time and effort. If something disrupts your day and you can’t do your 45-minute workout, you’ve lost the whole thing. But if you have three tiny habits anchored to different parts of your day, you might still hit two of them.

This is network effects from economics; the value of your habit system grows exponentially, not linearly. Each habit reinforces the identity of “someone who keeps promises to themselves,” and that meta-habit makes every subsequent habit easier. The trap I see clients fall into constantly is this: “I’m doing well, so I should do everything at once.” They’re riding the high of success, and they want to add meal prep AND daily workouts AND meditation AND journaling, and and and, etc. And then they crash and burn because they’ve gone from one habit above the action line to five habits below it. The slow and steady approach gets abandoned in favour of enthusiasm, and enthusiasm almost always loses to design.

Your job as a coach is to be the voice of reason when enthusiasm tries to sabotage success. One habit at a time. Master it. Let it become as automatic as brushing your teeth. Then consider adding another.

The Pitfalls That Will Kill Your Results (Even When Using the Fogg Behaviour Model)

Let me save you from the mistakes I made (and still sometimes catch myself making) even after learning the Fogg Behaviour Model.

Adding too many habits at once. Even three habits can be too many for most clients, especially if their lives are stressful or complicated. I’ve learned to ask: “Would you rather make progress on one thing or fail at three things?” The power of sequential habit building (master one, then add another), can’t be overstated.

This connects to the Pareto Principle (the 80/20 rule): 20% of actions create 80% of results. Multiple tiny habits done consistently will outperform sporadic heroic efforts every time. You want to identify and double down on that crucial 20%.

Making habits too ambitious too quickly. Your client’s enthusiasm is not a green light to increase difficulty. I know they’re excited. I know they want to go all in. Your job is to protect them from themselves. The Fogg Behaviour Model requires you to stay focused on ability even when motivation is high.

When a client tells me they’re ready to jump from ten-minute walks to training for a marathon, I say something like: “I love the enthusiasm. Let’s prove to ourselves that 15-minute walks are automatic first.” This isn’t just holding them back for the sake of it, it’s knowing the right-sized action for this person in this moment, not applying a one-size-fits-all template.

Using shame or disappointment when habits don’t stick. This one’s huge and directly contradicts everything the Fogg Behaviour Model teaches. If you respond to a client’s struggle with disappointment (even subtle disappointment, even in your tone) you become part of the problem. You become another person they’re letting down. That destroys trust and makes them less likely to be honest with you.

Instead, reframe “failure” as valuable diagnostic information using the Fogg Behaviour Model. “Okay, the habit didn’t stick. That tells us something about the design. Let’s figure out what needs to change.” No judgement. No shame. Just curiosity and problem-solving. This is behaviour forensics; examining what went wrong in the design, not what’s wrong with the person.

In Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan), humans need three things for intrinsic motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Tiny habits built on the Fogg Behaviour Model build competence through mastery of small wins. The choice of which habit to build creates autonomy. And your coaching relationship provides relatedness. When you respond with shame, you destroy all three simultaneously.

Treating all clients like they need the same level of difficulty. The stressed executive with three kids and a demanding job needs different-sized habits than the retired empty-nester with tons of free time. You’re not calibrating for fitness level when applying the Fogg Behaviour Model. You’re calibrating for life circumstances, cognitive load, and available bandwidth. What’s absurdly small for one client might still be too big for another.

This is where the art of coaching meets the science of the Fogg Behaviour Model. You need to develop the sensitivity to know where someone’s action line sits, given their current life context.

Forgetting to iterate. When a habit isn’t sticking, most coaches repeat the same pep talk, just louder. The better approach, rooted in the Fogg Behaviour Model, is redesign. Change the size of the behaviour. Change the anchor. Change the environment. Treat it like an experiment, not a test of character.

This is OODA Loop thinking from military strategist John Boyd: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. The Fogg Behaviour Model accelerates your OODA loop. When habits are tiny and well-prompted, you skip much of the “decide” phase. And when they don’t work, you quickly observe, orient to what failed, and redesign. This is tactical advantage.

Building elaborate programs that get bypassed by life circumstances doesn’t work. Better to be mobile and adaptive using the Fogg Behaviour Model principles (tiny, iterative habits) than rigid and impressive.

When Behaviours Still Aren’t Happening: The Fogg Behaviour Model Diagnostic

Even with all of this, sometimes habits don’t stick. When that happens, the Fogg Behaviour Model gives you a clear diagnostic framework.

I use the behaviour diagnostic process to assess which element was missing: motivation, ability, or prompt?

“Was the behaviour too hard in that moment?” This uncovers ability issues. Maybe what seemed easy when we talked about it turned out to have hidden friction. Maybe their life circumstances changed. Maybe they were more tired than expected. Ability is context-dependent, and what’s easy on Monday might be hard on Friday.

“Did something remind you to do it?” This reveals prompt problems. Maybe the anchor wasn’t as reliable as we thought. Maybe they don’t actually pour coffee every morning. Maybe the environmental prompt got moved. Without a reliable prompt, the behaviour won’t happen regardless of motivation and ability.

“Did you want to do it in that moment?” This is about motivation. And honestly, this is rarely the real issue when you’re properly applying the Fogg Behaviour Model. If ability and prompt are solid, even low motivation usually isn’t a dealbreaker. But sometimes life events tank motivation completely (a death, a job loss, a breakup, or something genuinely catastrophic), and in those cases, we might need to pause and come back to it.

The answers point you toward the solution using the Fogg Behaviour Model framework. Not another motivational speech. The actual structural problem that needs fixing.

I had a client who kept “forgetting” to do her evening habit. When we dug into it, the problem wasn’t memory (i.e. she didn’t forget about it). It was that her anchor (“after I finish dinner”) didn’t work because dinner time was chaotic with her kids. We changed the anchor to “after I brush my teeth,” which happened in her bathroom away from the chaos. The habit stuck immediately.

That’s not a motivation problem. That’s a design problem.

Here’s a thought experiment: What if your most successful clients aren’t your most motivated ones; they’re just your best-designed ones? This question reframes things wonderfully. When I look back at clients who got lasting results versus those who struggled, the difference wasn’t character or willpower. It was whether I’d properly applied the Fogg Behaviour Model principles to their specific circumstances.

Why the Fogg Behaviour Model Makes You a Better Coach (Not Just More Effective)

The Fogg Behaviour Model removes judgment and blame. When someone doesn’t follow through, I don’t wonder if they’re lazy or uncommitted. I don’t take it personally. I just look at the design and figure out what needs to be adjusted using the B=MAP framework.

Your clients will feel it too. They stop apologising for not being “good enough.” They stop beating themselves up. Because I’m not asking them to be better. I’m asking them to help me design better. This builds trust in a way that motivational coaching never could. Because I’m not testing their willpower every week. I’m designing for their success. And they know it. They feel it. They stick around because they finally have a coach who helps them feel capable instead of constantly behind.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, this is psychological flexibility. Accepting that internal experiences fluctuate and responding with workable strategies rather than avoidance or control attempts. The Fogg Behaviour Model embodies psychological flexibility. We accept that motivation fluctuates. We don’t fight it. We design around it.

Your identity as a coach shifts too, when you really start using these principles. You stop being a motivator and start being a designer. You stop being a cheerleader and start being an architect. This makes coaching more sustainable for you. There’s less emotional labour. Less getting drained by clients who aren’t “doing the work.” More problem-solving, more iteration, more partnership. The Fogg Behaviour Model changes the coaching relationship from hierarchical (I tell you what to do and you either comply or fail) to collaborative (we design experiments together and learn from the results).

I’m not saying motivation doesn’t matter or that you should never inspire your clients. I’m saying it can’t be your strategy. It can’t be what you’re banking on. Because it will fail you, and then you’ll blame your clients when really, you just didn’t have the right tools. Now you do. You have the Fogg Behaviour Model.

Your Action Plan: Implementing the Fogg Behaviour Model Tomorrow

So here’s how you implement the Fogg Behaviour Model in your next client session. Ask three questions:

“What’s one tiny habit that would make a difference?” Notice I said one. Not three. Not a whole overhaul. One thing. And make sure they choose it, not you. Their buy-in matters. This is motivational interviewing; eliciting their own reasons for change rather than imposing yours. When clients choose their own tiny habits using the Fogg Behaviour Model, adherence skyrockets.

“What existing routine could you attach it to?” Help them identify a solid anchor. Something they do every single day without fail. Test it: “Do you always brush your teeth at night? Do you always have coffee in the morning? Do you always take your shoes off when you get home?” Find the most reliable anchor. This is where the Fogg Behaviour Model’s power lies; in the connection between new and existing.

“How will you celebrate when you do it?” Work with them to create a specific celebration. Not “I’ll feel good about it.” Something physical. Something immediate. Something that feels genuine to them. The celebration is non-negotiable in the Fogg Behaviour Model. It’s what wires the habit in.

If you have clients who are already struggling with existing programs, you don’t have to start from scratch. Just retrofit with the Fogg Behaviour Model principles. Take whatever they’re supposed to be doing and ask: “What’s the smallest version of this that you could do every day, even on your worst day?” Start there.

And if you want to go deeper with this, and I really think you should, read BJ Fogg’s book “Tiny Habits.” Take his online course. This stuff sounds simple, but there’s nuance to applying the Fogg Behaviour Model correctly. The more you understand behaviour design, the better you’ll get at coaching it. Also explore “Atomic Habits” by James Clear, which builds on Fogg’s work, and “The Power of Habit” by Charles Duhigg. These three books together give you a comprehensive understanding of how the Fogg Behaviour Model fits into the broader landscape of habit formation research.

To be an effective coach, you ultimately must value design over discipline, systematisation over inspiration, and pragmatic effectiveness over impressive-sounding interventions.

The Counterintuitive Truth About Change

Here’s what I want you to remember: the less impressive the habit sounds, the more likely it is to create lasting change. This is the Tiny Habit Paradox, and the Fogg Behaviour Model explains why it’s true.

One push-up sounds ridiculous. But one push-up every day for a year is 365 push-ups more than zero. And more importantly, that one push-up becomes the foundation for everything else. It’s not about the push-up. It’s about proving to your client that they’re the kind of person who does what they say they’ll do. The Fogg Behaviour Model builds identity through action, not through intention.

That’s the shift that changes everything. Not the workout program. Not the meal plan. The identity shift that comes from keeping tiny promises to yourself.

Think about the butterfly effect from chaos theory where small initial conditions create large outcomes. The butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil causes a tornado in Texas. One tiny habit, properly designed using the Fogg Behaviour Model, isn’t just one habit. It’s a system change. It affects how your client sees themselves, how they approach other challenges, and how they show up in the world.

Viktor Frankl wrote in “Man’s Search for Meaning”: “Don’t aim at success. The more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it.” The Fogg Behaviour Model embodies this wisdom. We don’t aim at transformation. We aim at one push-up. And transformation emerges as a side effect of the system we’ve designed.

Stop being a cheerleader. Start being a behaviour designer. Stop testing your clients’ willpower and start designing for their success. Stop asking “Are they motivated enough?” Start asking, “Is this behaviour above or below the action line?”

Because when your clients finally experience what sustainable change actually feels like, and when they’re not relying on motivation they don’t have, when habits feel automatic instead of effortful, when they’re building momentum instead of constantly starting over, that will transform your coaching practice.

They tell their friends. They stay with you for years. They get results that last. And you get to do the work you actually signed up for: helping people change their lives, not just giving them plans they won’t follow.

The ancient Greeks had a word, eudaimonia, which is often translated as “flourishing” or “the good life.” It wasn’t about happiness in the modern sense. It was about living in accordance with virtue, about becoming who you’re capable of becoming. Aristotle argued that eudaimonia comes not from peak experiences but from sustained right action. The Fogg Behaviour Model is a technology for eudaimonia. It makes sustained right action possible by making it easy, automatic, and reinforcing.

Now, if all of this isn’t getting through to you, a question you should at least grapple with is: What if willpower isn’t a virtue but a design failure? This might be the most important question the Fogg Behaviour Model asks us to consider. We’ve been taught to admire willpower, to see it as character. But what if it’s actually just evidence of poor design? What if people who seem to have great willpower simply have better systems, better environments, better-designed habits? The Fogg Behaviour Model suggests this is true. And if it is, everything changes about how we coach.

That’s what’s on the other side of this shift to using the Fogg Behaviour Model. You’re not just teaching behaviour change anymore. You’re engineering inevitability. You’re not hoping your clients stay motivated. You’re designing systems where motivation becomes irrelevant. You’re not inspiring transformation. You’re architecting it, one tiny habit at a time.

For those of you ready to take the next step in professional development, we offer advanced courses like our Nutrition Coach Certification, which is designed to help you guide clients through sustainable, evidence-based nutrition change with confidence, while our Exercise Program Design Course focuses on building effective, individualised training plans that actually work in the real world. Beyond that, we’ve created specialised courses so you can grow in the exact areas that matter most for your journey as a coach.

If you want to keep sharpening your coaching craft, we’ve built a free Content Hub filled with resources for coaches. Inside, you’ll find the Coaches Corner, which has a collection of tools, frameworks, and real-world insights you can start using right away. We also share regular tips and strategies on Instagram and YouTube, so you’ve always got fresh ideas and practical examples at your fingertips. And if you want everything delivered straight to you, the easiest way is to subscribe to our newsletter so you never miss new material.

References and Further Reading

Agha S, Tollefson D, Paul S, Green D, Babigumira JB. Use of the Fogg Behavior Model to Assess the Impact of a Social Marketing Campaign on Condom Use in Pakistan. J Health Commun. 2019;24(3):284-292. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1597952 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30945612/

Agha S. Use of a Practitioner-Friendly Behavior Model to Identify Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination and Other Behaviors. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(8):1261. Published 2022 Aug 5. doi:10.3390/vaccines10081261 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36016149/

Yin HH, Knowlton BJ. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(6):464-476. doi:10.1038/nrn1919 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16715055/

Ashby FG, Turner BO, Horvitz JC. Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14(5):208-215. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.02.001 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20207189/

Seger CA, Spiering BJ. A critical review of habit learning and the Basal Ganglia. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:66. Published 2011 Aug 30. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00066 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21909324/

Schweiger Gallo I, Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: a look back at fifteen years of progress. Psicothema. 2007;19(1):37-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17295981/

Orbell S, Hodgkins S, Sheeran P. Implementation Intentions and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23(9):945-954. doi:10.1177/0146167297239004 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29506445/

Brandstätter V, Lengfelder A, Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions and efficient action initiation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(5):946-960. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.946 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11708569/

Baumeister RF, André N, Southwick DA, Tice DM. Self-control and limited willpower: Current status of ego depletion theory and research. Curr Opin Psychol. 2024;60:101882. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101882 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39278166/

Pignatiello GA, Martin RJ, Hickman RL Jr. Decision fatigue: A conceptual analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):123-135. doi:10.1177/1359105318763510 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6119549/

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11392867/

Patrick H, Williams GC. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:18. Published 2012 Mar 2. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-18 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3323356/

Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(605):664-666. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659466 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3505409/

Gardner B, Arden MA, Brown D, et al. Developing habit-based health behaviour change interventions: twenty-one questions to guide future research. Psychol Health. 2023;38(4):518-540. doi:10.1080/08870446.2021.2003362 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34779335/

Michaelsen MM, Esch T. Understanding health behavior change by motivation and reward mechanisms: a review of the literature. Front Behav Neurosci. 2023;17:1151918. Published 2023 Jun 19. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1151918 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37405131/